Quran the First Arabic Book.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dilmun Bioarchaeology Project: a First Look at the Peter B. Cornwall Collection at the Phoebe A

UC Berkeley Postprints Title The Dilmun Bioarchaeology Project: A First Look at the Peter B. Cornwall Collection at the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2z06r9bj Journal Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy, 23(1) ISSN 09057196 Authors Porter, Benjamin W Boutin, Alexis T Publication Date 2012 DOI 10.1111/j.1600-0471.2011.00347.x Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Arab. arch. epig. 2012: 23: 35–49 (2012) Printed in Singapore. All rights reserved The Dilmun Bioarchaeology Project: a first look at the Peter B. Cornwall Collection at the Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology This article presents an overview of the Peter B. Cornwall collection in the Phoebe A. Arabia Hearst Museum of Anthropology at the University of California, Berkeley. Cornwall Benjamin W. Porter conducted an archaeological survey and excavation project in eastern Saudi Arabia 240 Barrows Hall, #1940, and Bahrain in 1940 and 1941. At least twenty-four burial features were excavated in Department of Near Eastern Bahrain from five different tumuli fields, and surface survey and artefact collection Studies, University of California, took place on at least sixteen sites in Saudi Arabia and Bahrain. The skeletal evidence, Berkeley, CA 94720 USA objects and faunal remains were subsequently accessioned by the Hearst Museum. e-mail: [email protected] The authors recently formed the Dilmun Bioarchaeology Project to investigate this collection. This article provides background information on Cornwall?s expedition Alexis T. Boutin and an overview of the collection. Additionally, skeletal evidence and associated Stevenson Hall 2054A, Depart- objects from two tumuli in Bahrain, D1 and G20, are presented to illustrate the ment of Anthropology, Sonoma collection?s potential contribution. -

(Les Guides Bleus) Paris 1956 Reiseführer Vorderer O

Autor Autor Titel Ort Jahr Sachgebiet 1 Sachgebiet 2 Anmerkungen Le Moyen-Orient (Les Guides Paris 1956 Reiseführer Vorderer Orient Bleus) Bosworth, C. E. The Islamic Dynasties Edinburgh 1980 28 Islam Geschichte Islam American Doctoral Selim, George Dissertations on the Arab Washington 1976 01 Bibliographien Orientalistik Dimitri World 1833-1974. Second Edition A Bibliography of the Writings Attal, Robert Jerusalem 1975 01 Bibliographien Orientalistik of Prof. Shelomo Dov Goitein Bibliografia de Don Manuel Madrid 1952 01 Bibliographien Spanien, Islam Gomez Moreno Bibliothekswesen und Bibliographie in der UdSSR. Übersetzungen aus der Großen Sowjetenzyklopädie (Schriftenreihe des Arbeitskreises der Berlin o.J. 01 Bibliographien Sowjetunion Gesellschaftswissenschaftlichen Beratungsstellen an den dem Staatssekretariat für Hochschulwesen unterstellten wissenschaftlichen Bibliotheken; Heft 2) Deutsche Autoren in Arabischer Sprache und Ule, Wolfgang Bonn-Bad- Arabische Autoren über 1974 01 Bibliographie Orientalistik (Hrsg.) Godesberg Deutsche und Deutschland. Eine Bibliographie. Egypt. Subject Catalogue. Vol. I. (Egyptian National Library Kairo 1957 01 Bibliographien Ägypten Publications) file:///C|/Dokumente%20und%20Einstellungen/DBinder/Desktop/Brisch.htm (1 von 129)29.04.2008 15:22:56 Autor Einhundert Jahre Orientteppich- Enay, Marc- Literatur 1877-1977. Edouard - Hannover 1977 01 Bibliographien Orientalistik Bibliographie der Bücher und Azadi, Siawosch Kataloge. Europäische Bücher und neuere Veröffentlichungen über die o.O. o.J. 01 Bibliographien -

Lesson 1 Makharijul Huruf

Foundation In Quranic Studies Lesson 1 Makharijul Huruf Lesson Outline • Meaning of Tajwid • Basis from the Quran and Hadith on reciting with tajwid • Topics covered in Tajwid as a subject • Introduction to the studies of Makharijul Huruf • The Articulation Points of Letters • The Areas of Articulation Points Meaning of Tajwid Linguistically, Tajwid means: 1. Proficiency 2. Doing something well Meaning of Tajwid In application, Tajwid is the science of learning the Arabic letters and • their correct phonetic articulations • the qualities of certain letters when they are pronounced • the significance of different kinds of punctuation marks used in the Quran. The Importance of Tajwid • At the time of the Prophet , may Peace and Blessings be upon him, there was no need for people to study Tajwid because they talked with what is now known as the Tajwid as it was natural for them • When the Arabs started mixing with the non-Arabs and as Islam spread, mistakes in the Quranic recitation began to appear, so the scholars had to record the rules • Presently, because the everyday Arabic that Arabs speak has changed so much from the Classical Arabic with which the Quran was revealed, even the Arabs have to learn the Tajwid Basis of Learning Tajwid • Scholars of Quran of the opinion that reciting the Quran correctly while observing the rules of recitation is an obligation upon each and every Muslim. • This is inline with verse 4, Surah Al-Muzzammil: “…And recite the Quran in slow, measured rhythmic tones.” – Al-Muzzammil 73:4 Basis of Learning Tajwid • The noble Prophet pbuh told his followers about the rewards of reciting, studying and teaching the Quran as follows: َ ر ُ َ ََّ ر ُ َ َ ََّ »خ ُْيك رم َم رن ت َعل َم الق ررآن َوعل َم ُ ه« “The best among you are those who learn the Quran and teach it to others.” – Reported by al-Bukhari, Ibn Majah and Ad-Darimi. -

Report Resumes Ed 012 361 the Structure of the Arabic Language

REPORT RESUMES ED 012 361 THE STRUCTURE OF THE ARABIC LANGUAGE. BY- YUSHMANOV; N.V. CENTER FOR APPLIED LINGUISTICS, WASHINGTON,D.C. REPORT NUMBER NDEA-VI-128 PUB DATE EDRS PRICE MF-$0.50 HC-$3.76 94F. DESCRIPTORS- *ARABIC, *GRAMMAR: TRANSLATION,*PHONOLOGY, *LINGUISTICS, *STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS, DISTRICTOF COLUMBIA THE PRESENT STUDY IS A TRANSLATIONOF THE WORK "STROI ARABSK0G0 YAZYKA" BY THE EMINENT RUSSIANLINGUIST AND SEMITICS SCHOLAR, N.Y. YUSHMANOV. IT DEALSCONCISELY WITH THE POSITION OF ARABIC AMONG THE SEMITICLANGUAGES AND THE RELATION OF THE LITERARY (CLASSICAL)LANGUAGE TO THE VARIOUS MODERN SPOKEN DIALECTS, AND PRESENTS ACONDENSED BUT COMPREHENSIVE SUMMARY OF ARABIC PHONOLOGY ANDGRAMMAR. PAGES FROM SAMPLE TEXTS ARE INCLUDED. THIS REPORTIS AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY MOSHE PERLMANN. (IC) w4ur;,e .F:,%ay.47A,. :; -4t N. V. Yushmanov The Structure of the Arabic Language Trar Mated from the Russian by Moshe Perlmann enter for Applied Linguistics of theModern Language Association of America /ashington D.C. 1961 N. V. Yushmanov The Structure of the Arabic Language. Translated from the Russian by Moshe Perlmann Center for Applied Linguistics of the Modern Language Association of America Washington D.C. 1961 It is the policy of the Center for Applied Linguistics to publish translations of linguistic studies and other materials directly related to language problems when such works are relatively inaccessible because of the language in which they are written and are, in the opinion of the Center, of sufficient merit to deserve publication. The publication of such a work by the Center does not necessarily mean that the Center endorses all the opinions presented in it or even the complete correctness of the descriptions of facts included. -

The Qur'anic Manuscripts

The Qur'anic Manuscripts Introduction 1. The Qur'anic Script & Palaeography On The Origins Of The Kufic Script 1. Introduction 2. The Origins Of The Kufic Script 3. Martin Lings & Yasin Safadi On The Kufic Script 4. Kufic Qur'anic Manuscripts From First & Second Centuries Of Hijra 5. Kufic Inscriptions From 1st Century Of Hijra 6. Dated Manuscripts & Dating Of The Manuscripts: The Difference 7. Conclusions 8. References & Notes The Dotting Of A Script And The Dating Of An Era: The Strange Neglect Of PERF 558 Radiocarbon (Carbon-14) Dating And The Qur'anic Manuscripts 1. Introduction 2. Principles And Practice 3. Carbon-14 Dating Of Qur'anic Manuscripts 4. Conclusions 5. References & Notes From Alphonse Mingana To Christoph Luxenberg: Arabic Script & The Alleged Syriac Origins Of The Qur'an 1. Introduction 2. Origins Of The Arabic Script 3. Diacritical & Vowel Marks In Arabic From Syriac? 4. The Cover Story 5. Now The Evidence! 6. Syriac In The Early Islamic Centuries 7. Conclusions 8. Acknowledgements 9. References & Notes Dated Texts Containing The Qur’an From 1-100 AH / 622-719 CE 1. Introduction 2. List Of Dated Qur’anic Texts From 1-100 AH / 622-719 CE 3. Codification Of The Qur’an - Early Or Late? 4. Conclusions 5. References 2. Examples Of The Qur'anic Manuscripts THE ‘UTHMANIC MANUSCRIPTS 1. The Tashkent Manuscript 2. The Al-Hussein Mosque Manuscript FIRST CENTURY HIJRA 1. Surah al-‘Imran. Verses number : End Of Verse 45 To 54 And Part Of 55. 2. A Qur'anic Manuscript From 1st Century Hijra: Part Of Surah al-Sajda And Surah al-Ahzab 3. -

In Aswan Arabic

University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics Volume 22 Issue 2 Selected Papers from New Ways of Article 17 Analyzing Variation (NWAV 44) 12-2016 Ethnic Variation of */tʕ/ in Aswan Arabic Jason Schroepfer Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl Recommended Citation Schroepfer, Jason (2016) "Ethnic Variation of */tʕ/ in Aswan Arabic," University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: Vol. 22 : Iss. 2 , Article 17. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol22/iss2/17 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol22/iss2/17 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ethnic Variation of */tʕ/ in Aswan Arabic Abstract This study aims to provide some acoustic documentation of two unusual and variable allophones in Aswan Arabic. Although many rural villages in southern Egypt enjoy ample linguistic documentation, many southern urban areas remain understudied. Arabic linguists have investigated religion as a factor influencing linguistic ariationv instead of ethnicity. This study investigates the role of ethnicity in the under-documented urban dialect of Aswan Arabic. The author conducted sociolinguistic interviews in Aswan from 2012 to 2015. He elected to measure VOT as a function of allophone, ethnicity, sex, and age in apparent time. The results reveal significant differences in VOT lead and lag for the two auditorily encoded allophones. The indigenous Nubians prefer a different pronunciation than their Ṣa‘īdī counterparts who trace their lineage to Arab roots. Women and men do not demonstrate distinct pronunciations. Age also does not appear to be affecting pronunciation choice. However, all three variables interact with each other. -

The Islamic Traditions of Cirebon

the islamic traditions of cirebon Ibadat and adat among javanese muslims A. G. Muhaimin Department of Anthropology Division of Society and Environment Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies July 1995 Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Muhaimin, Abdul Ghoffir. The Islamic traditions of Cirebon : ibadat and adat among Javanese muslims. Bibliography. ISBN 1 920942 30 0 (pbk.) ISBN 1 920942 31 9 (online) 1. Islam - Indonesia - Cirebon - Rituals. 2. Muslims - Indonesia - Cirebon. 3. Rites and ceremonies - Indonesia - Cirebon. I. Title. 297.5095982 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Teresa Prowse Printed by University Printing Services, ANU This edition © 2006 ANU E Press the islamic traditions of cirebon Ibadat and adat among javanese muslims Islam in Southeast Asia Series Theses at The Australian National University are assessed by external examiners and students are expected to take into account the advice of their examiners before they submit to the University Library the final versions of their theses. For this series, this final version of the thesis has been used as the basis for publication, taking into account other changes that the author may have decided to undertake. In some cases, a few minor editorial revisions have made to the work. The acknowledgements in each of these publications provide information on the supervisors of the thesis and those who contributed to its development. -

Dedan & Lihyan Kingdom

he first settlement at the al ‘Ula Famous Red Cliff Tombs a war between the two important Toasis was erected about 4,000 trading centers. In 553BCE Neo- years ago and developed into one of Most of the over 100 rock tombs Babylonian king Nabonid mentioned the most important trading posts on are found at the foot of the red on a stele, discovered at Harran in the famous Incense Route. colored sandstone cliffs right next today’s Syria, that the king of Dedan to the sprawling capital. The square was his vassal. It is no wonder, 1,000 years later tombs were cut two meters deep with the rise of the Nabataean empire, and horizontally into the rock face, From other known historic sources, that Mada’in Saleh was erected or into the rock bed floors at the Nabonid subdued the whole northern just 20kms north of it. Dedan, or mountain base. These tombs, which region of the Arabian Peninsula. This Khuraibah as it is called, was one of we can still see today, were created included the kingdom of Adumatu the few ancient cities, which allowed during the 5th century BCE and are (modern-day al Jawf) as well as various ethnic tribes living next to either single or collective tombs with Tayma, which he made his new each other in peace and erecting funerary inscriptions. Only a few are capital for over 10 years. separate temples to worship their decorated with lion figures to indicate The reported peaceful conversion main deities Dhu Ghaibat, Nikrah and royal status. -

Arabic and Contact-Induced Change Christopher Lucas, Stefano Manfredi

Arabic and Contact-Induced Change Christopher Lucas, Stefano Manfredi To cite this version: Christopher Lucas, Stefano Manfredi. Arabic and Contact-Induced Change. 2020. halshs-03094950 HAL Id: halshs-03094950 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03094950 Submitted on 15 Jan 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Arabic and contact-induced change Edited by Christopher Lucas Stefano Manfredi language Contact and Multilingualism 1 science press Contact and Multilingualism Editors: Isabelle Léglise (CNRS SeDyL), Stefano Manfredi (CNRS SeDyL) In this series: 1. Lucas, Christopher & Stefano Manfredi (eds.). Arabic and contact-induced change. Arabic and contact-induced change Edited by Christopher Lucas Stefano Manfredi language science press Lucas, Christopher & Stefano Manfredi (eds.). 2020. Arabic and contact-induced change (Contact and Multilingualism 1). Berlin: Language Science Press. This title can be downloaded at: http://langsci-press.org/catalog/book/235 © 2020, the authors Published under the Creative Commons Attribution -

Bauhistorische Untersuchungen Am Almaqah-Heiligtum Von Sirwah Vom

BAUHISTORISCHE UNTERSUCHUNGEN AM ALMAQAH-HEILIGTUM VON SIRWAH VOM KULTPLATZ ZUM HEILIGTUM Von der Fakultät Architektur, Bauingenieurwesen und Stadtplanung der Brandenburgischen Technischen Universität Cottbus zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Doktor der Ingenieurwissenschaften (Dr.-Ing.) genehmigte Dissertation vorgelegt von Dipl.-Ing. Nicole Röring geboren am 18.01.1972 in Lippstadt Gutachter: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Adolf Hoffmann Gutachter: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Klaus Rheidt Gutachter: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Ernst-Ludwig Schwandner Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 06.10.2006 Band 1/Text In Erinnerung an meinen Vater Engelbert Röring Zusammenfassung Das Almaqah-Heiligtum von Sirwah befindet sich auf der südarabischen Halbinsel im Nordjemen etwa 80 km östlich der heutigen Hauptstadt Sanaa und ca. 40 km westlich von Marib, der einstigen Hauptstadt des Königreichs von Saba. Das Heiligtum, dessen Blütezeit auf das 7. Jh. v. Chr. zurückgeht, war dem sabäischen Reichsgott Almaqah geweiht. Das Heiligtum wird von einer bis zu 10 m hoch anstehenden und etwa 90 m langen, gekurvten Umfassungsmauer eingefasst. Im Nordwesten der Anlage sind zwei Propyla vorgelagert, die die Haupterschließungsachse bilden. Quer zum Inneren Propylon erstreckt sich entlang der Westseite eine einst überdachte Terrasse mit unterschiedlichen Einbauten. Kern der Gesamtanlage bildet ein Innenhof, der von der Umfassungsmauer mit einem umlaufenden Wehrgang gerahmt wird. Den Innenhof prägen unterschiedliche Einbauten rechteckiger Kubatur sowie insbesondere das große Inschriftenmonument, des frühen sabäischen Herrschers, Mukarrib Karib`il Watar, das eins der wichtigsten historischen Quellen Südwestarabiens darstellt. Die bauforscherische Untersuchung des Almaqah-Heiligtums von Sirwah konnte eine sukzessive Entwicklung eines Kultplatzes zu einem ‘internationalen’ Sakralkomplex nachweisen, die die komplexe Chronologie der Baulichkeiten des Heiligtums und eine damit einhergehende mindestens 1000jährige Nutzungszeit mit insgesamt fünfzehn Entwicklungsphasen belegt, die sich wiederum in fünf große Bauphasen gliedern lassen. -

First Arabic Words Free

FREE FIRST ARABIC WORDS PDF David Melling | 48 pages | 10 Aug 2009 | Oxford University Press | 9780199111350 | English, Arabic | Oxford, United Kingdom First Words: Arabic For Kids on the App Store Out of stock - Join the waitlist to be emailed when this product becomes available. This book is an amazing picture dictionary for the kids who are just starting to learn Arabic. Children will learn their first Arabic word with colorful and amusing pictures, and they will never get bored. The author has categorized the words by theme so that children can learn the words from the things around First Arabic Words. Only logged in customers who have purchased this product may leave a review. Log in. Sold out. Click to enlarge. Next product. Join waitlist. Add to wishlist. Share Facebook Twitter Pinterest linkedin Telegram. Additional information Weight 0. Reviews 0 Reviews There are no reviews yet. We only ship within the United States and Puerto Rico for non- partner institutions. All orders are processed and First Arabic Words during normal business hours Monday-Friday, from 9 a. Estimated ship times are listed below. You may First Arabic Words like…. About this Book This picture dictionary has more than words. It uses color illustration to enhance the reading and. Read First Arabic Words. Quick view. In this book, the author has described some best chosen educational stories from the First Arabic Words of our beloved Prophet Hazrat. Select options. Word by Word 2nd Edition by Steven j. Add to cart. In this book, children will know about the first four caliphs of Islam- Abu Bakr, Umar ibn Al-khatta, who were. -

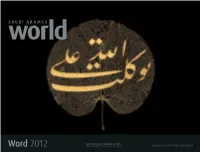

You May View It Or Download a .Pdf Here

“I put my trust in God” (“Tawakkaltu ‘ala ’illah”) Word 2012 —Arabic calligraphy in nasta’liq script on an ivy leaf 42976araD1R1.indd 1 11/1/11 11:37 PM Geometry of the Spirit WRITTEN BY DAVID JAMES alligraphy is without doubt the most original con- As well, there were regional varieties. From Kufic, Islamic few are the buildings that lack Hijazi tribution of Islam to the visual arts. For Muslim cal- Spain and North Africa developed andalusi and maghribi, calligraphy as ornament. Usu- Cligraphers, the act of writing—particularly the act of respectively. Iran and Ottoman Turkey both produced varie- ally these inscriptions were writing the Qur’an—is primarily a religious experience. Most ties of scripts, and these gained acceptance far beyond their first written on paper and then western non-Muslims, on the other hand, appreciate the line, places of origin. Perhaps the most important was nasta‘liq, transferred to ceramic tiles for Kufic form, flow and shape of the Arabic words. Many recognize which was developed in 15th-century Iran and reached a firing and glazing, or they were that what they see is more than a display of skill: Calligraphy zenith of perfection in the 16th century. Unlike all earlier copied onto stone and carved is a geometry of the spirit. hands, nasta‘liq was devised to write Persian, not Arabic. by masons. In Turkey and Per- The sacred nature of the Qur’an as the revealed word of In the 19th century, during the Qajar Dynasty, Iranian sia they were often signed by Maghribıi God gave initial impetus to the great creative outburst of cal- calligraphers developed from nasta‘liq the highly ornamental the master, but in most other ligraphy that began at the start of the Islamic era in the sev- shikastah, in which the script became incredibly complex, con- places we rarely know who enth century CE and has continued to the present.