Policing the Post-Racial: Visual Rhetorics of Racial Backlash

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African Americans' Response to Police Brutality: the Black Lives

Mohamed Khider University of Biskra Faculty of Letters and Languages Department of Foreign Languages MASTER THESIS Letters and Foreign Languages English Language Literature and Civilization Submitted and Defended by: Imane CHEHABA African Americans’ Response to Police Brutality: The Black Lives Matter Strategy and Agenda Board of Examiners : Dr Salim KERBOUA PHD University of Biskra Superviser Mr Abdelnacer BENADELRREZAK MAB University of Biskra Examiner Mrs Asmaa CHRIET MAB University of Biskra Examiner Mrs Maymouna HADDAD MAB University of Biskra Chairperson Academic Year : 2018-2019 Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my siblings, Karim, Yacine and Doudi. To my grandparents, my uncle and my auntie who have always been a constant source of encouragement and support during the challenges of my whole college life. To my bestie Malak Rahmouni whom I am truly grateful for having in my life. This work is also dedicated to my mother. Mom, thank you for the unconditional love that you provide me with, thank you for every single sacrifice. I dedicate this work to my teachers and my friends. Thank you everyone i Acknowledgement This work would not have been possible without the efforts of each one of my teachers. I am especially indebted to my teacher and supervisor Dr.Salim Kerboua. From this platform, I would like to thank him for developing my interest in the topic and for providing me with beneficial sources and guidance. I am grateful to all of those with whom I have had the honor to work during this journey. I would like to thank all of my teachers for providing me with extensive academic guidance. -

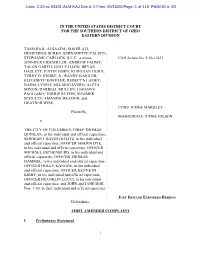

Case: 2:20-Cv-03431-ALM-KAJ Doc #: 2 Filed: 09/16/20 Page: 1 of 118 PAGEID #: 83

Case: 2:20-cv-03431-ALM-KAJ Doc #: 2 Filed: 09/16/20 Page: 1 of 118 PAGEID #: 83 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF OHIO EASTERN DIVISION TAMARA K. ALSAADA; MAHIR ALI; : DEMETRIUS BURKE; BERNADETTE CALVEY;: STEPHANIE CARLOCK; S.L.C., a minor; : Civil Action No. 2:20cv3431 JENNIFER EIDEMILLER; ANDREW FAHMY; : TALON GARTH; HOLLY HAHN, BRYAN : HAZLETT; JUSTIN HORN; KURGHAN HORN; : TERRY D. HUBBY, Jr.; RANDY KAIGLER; : ELIZABETH KOEHLER; REBECCA LAMEY; : NADIA LYNCH; MIA MOGAVERO; ALETA : MIXON; DARRELL MULLEN; LEEANNE : PAGLIARO; TORRIE RUFFIN; SUMMER : SCHULTZ; AMANDA WELDON; and : HEATHER WISE, : : CHIEF JUDGE MARBLEY Plaintiffs, : : MAGISTRATE JUDGE JOLSON v. : : THE CITY OF COLUMBUS; CHIEF THOMAS : QUINLAN, in his individual and official capacities; : SERGEANT DAVID GITLITZ, in his individual : and official capacities; OFFICER SHAWN DYE, : in his individual and official capacities; OFFICER : MICHAEL ESCHENBURG, in his individual and : official capacities; OFFICER THOMAS : HAMMEL, in his individual and official capacities; : OFFICER HOLLY KANODE, in her individual : and official capacities; OFFICER KENNETH : KIRBY, in his individual and official capacities; : OFFICER FRANKLIN LUCCI, in his individual : and official capacities; and JOHN and JANE DOE, : Nos. 1-30, in their individual and official capacities, : : : JURY DEMAND ENDORSED HEREON Defendants. : FIRST AMENDED COMPLAINT I. Preliminary Statement 1 Case: 2:20-cv-03431-ALM-KAJ Doc #: 2 Filed: 09/16/20 Page: 2 of 118 PAGEID #: 84 1. On May 25, 2020, the killing of George Floyd, who was being arrested for allegedly passing a counterfeit $20 bill to buy cigarettes, by then Minneapolis Police Department Officer Derek Chauvin was live-streamed over the Internet for eight minutes and 46 seconds and later televised around the world. -

Erie County Clerk 09/14/2020 10:09 Pm Index No

FILED: ERIE COUNTY CLERK 09/14/2020 10:09 PM INDEX NO. 807664/2020 NYSCEF DOC. NO. 114 RECEIVED NYSCEF: 09/14/2020 SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK COUNTY OF ERIE BUFFALO POLICE BENEVOLENT ASSOCIATION, INC.; and BUFFALO PROFESSIONAL FIREFIGHTERS ASSOCIATION INC., LOCAL 282, IAFF, ALF-CIO, Petitioners/Plaintiffs, v. INDEX NO: 807664/2020 BYRON W. BROWN, in his official capacity as Mayor of the City of Buffalo; the CITY OF BUFFALO; BYRON C. LOCKWOOD, in his official capacity as Commissioner of the Buffalo Police Department; the BUFFALO POLICE DEPARTMENT; WILLIAM RENALDO, in his official capacity as Commissioner of the Buffalo Fire Department; and the BUFFALO FIRE DEPARTMENT, Respondents/Defendants. [PROPOSED] BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW, LATINOJUSTICE PRLDEF, LAW FOR BLACK LIVES, AND NYU SCHOOL OF LAW CENTER ON RACE, INEQUALITY, AND THE LAW IN OPPOSITION TO PETITIONERS’/PLAINTIFFS’ APPLICATION FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION FILED: ERIE COUNTY CLERK 09/14/2020 10:09 PM INDEX NO. 807664/2020 NYSCEF DOC. NO. 114 RECEIVED NYSCEF: 09/14/2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 1 ARGUMENT ................................................................................................................................. 4 I. PUBLIC DISCLOSURE OF POLICE MISCONDUCT AND DISCIPLINE RECORDS IS ESSENTIAL FOR TRANSPARENCY AND POLICE ACCOUNTABILITY. -

An End to Antisemitism!

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds An End to Antisemitism! Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman Volume 5 Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman ISBN 978-3-11-058243-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-067196-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-067203-9 DOI https://10.1515/9783110671964 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Library of Congress Control Number: 2021931477 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, Lawrence H. Schiffman, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com Cover image: Illustration by Tayler Culligan (https://dribbble.com/taylerculligan). With friendly permission of Chicago Booth Review. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com TableofContents Preface and Acknowledgements IX LisaJacobs, Armin Lange, and Kerstin Mayerhofer Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds: Introduction 1 Confronting Antisemitism through Critical Reflection/Approaches -

Black Lives Matter As Reproductive Justice

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Framing Murder: Black Lives Matter as Reproductive Justice A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Sociology by Anna H. Chatillon(-Reed) Committee in charge: Professor George Lipsitz, Co-Chair Professor Beth Schneider, Co-Chair Professor Zakiya T. Luna March 2017 The thesis of Anna H. Chatillon(-Reed) is approved. ____________________________________________ Zakiya T. Luna ____________________________________________ George Lipsitz, Committee Co-Chair ____________________________________________ Beth Schneider, Committee Co-Chair February 2017 Framing Murder: Black Lives Matter as Reproductive Justice Copyright © 2017 by Anna H. Chatillon(-Reed) iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank my committee, Professors George Lipsitz, Beth Schneider, and Zakiya Luna, for their support for this “project in our care” and for their feedback through several drafts of the manuscript. I would also like to gratefully acknowledge Dr. Wendy Rosen, whose guidance was invaluable in seeing this project to completion. To those people killed, assaulted, or otherwise targeted by racialized police brutality, and to their families: I dedicate this thesis to you. iv ABSTRACT Framing Murder: Black Lives Matter as Reproductive Justice by Anna H. Chatillon(-Reed) Feminist and anti-racist organizing in the United States has often concentrated on single axes of oppression: gender and race, respectively (Crenshaw 1991). Yet intersectionality — which poses that such systems of oppression interact, and therefore cannot be understood alone (Crenshaw1989) — is increasingly invoked not only in academic work but in a broad range of activist spaces. On the Black Lives Matter website and in interviews, for instance, movement leaders have framed the movement as intersectional. -

Blacklivesmatter and Feminist Pedagogy: Teaching a Movement Unfolding

ISSN: 1941-0832 #BlackLivesMatter and Feminist Pedagogy: Teaching a Movement Unfolding by-Reena N. Goldthree and Aimee Bahng BLACK LIVES MATTER - FERGUSON SOLIDARITY WASHINGTON ETHICAL SOCIETY, 2014 (IMAGE: JOHNNY SILVERCLOUD) RADICAL TEACHER 20 http://radicalteacher.library.pitt.edu No. 106 (Fall 2016) DOI 10.5195/rt.2016.338 college has the lowest percentage of faculty of color. 9 The classroom remains the most radical space Furthermore, Dartmouth has ―earned a reputation as one of possibility in the academy. (bell hooks, of the more conservative institutions in the nation when it Teaching to Transgress) comes to race,‖ due to several dramatic and highly- publicized acts of intolerance targeting students and faculty n November 2015, student activists at Dartmouth of color since the 1980s.10 College garnered national media attention following a I Black Lives Matter demonstration in the campus‘s main The emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement— library. Initially organized in response to the vandalism of a following the killings of Trayvon Martin in 2013 and of Eric campus exhibit on police brutality, the events at Garner and Michael Brown in 2014—provided a language Dartmouth were also part of the national #CollegeBlackout for progressive students and their allies at Dartmouth to mobilizations in solidarity with student activists at the link campus activism to national struggles against state University of Missouri and Yale University. On Thursday, violence, white supremacy, capitalism, and homophobia. November 12th, the Afro-American Society and the The #BlackLivesMatter course at Dartmouth emerged as campus chapter of the National Association for the educators across the country experimented with new ways Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) urged students to to learn from and teach with a rapidly unfolding, multi- wear black to show support for Black Lives Matter and sited movement. -

A Herstory of the #Blacklivesmatter Movement by Alicia Garza

A Herstory of the #BlackLivesMatter Movement by Alicia Garza From The Feminist Wire, October 7, 2014 I created #BlackLivesMatter with Patrisse Cullors and Opal Tometi, two of my sisters, as a call to action for Black people after 17-year-old Trayvon Martin was post-humously placed on trial for his own murder and the killer, George Zimmerman, was not held accountable for the crime he committed. It was a response to the anti-Black racism that permeates our society and also, unfortunately, our movements. Black Lives Matter is an ideological and political intervention in a world where Black lives are systematically and intentionally targeted for demise. It is an affirmation of Black folks’ contributions to this society, our humanity, and our resilience in the face of deadly oppression. We were humbled when cultural workers, artists, designers and techies offered their labor and love to expand #BlackLivesMatter beyond a social media hashtag. Opal, Patrisse, and I created the infrastructure for this movement project—moving the hashtag from social media to the streets. Our team grew through a very successful Black Lives Matter ride, led and designed by Patrisse Cullors and Darnell L. Moore, organized to support the movement that is growing in St. Louis, MO, after 18-year old Mike Brown was killed at the hands of Ferguson Police Officer Darren Wilson. We’ve hosted national conference calls focused on issues of critical importance to Black people working hard for the liberation of our people. We’ve connected people across the country working to end the various forms of injustice impacting our people. -

Appendix: Famous Actors/ Actresses Who Appeared in Uncle Tom's Cabin

A p p e n d i x : F a m o u s A c t o r s / Actresses Who Appeared in Uncle Tom’s Cabin Uncle Tom Ophelia Otis Skinner Mrs. John Gilbert John Glibert Mrs. Charles Walcot Charles Walcott Louisa Eldridge Wilton Lackaye Annie Yeamans David Belasco Charles R. Thorne Sr.Cassy Louis James Lawrence Barrett Emily Rigl Frank Mayo Jennie Carroll John McCullough Howard Kyle Denman Thompson J. H. Stoddard DeWolf Hopper Gumption Cute George Harris Joseph Jefferson William Harcourt John T. Raymond Marks St. Clare John Sleeper Clarke W. J. Ferguson L. R. Stockwell Felix Morris Eva Topsy Mary McVicker Lotta Crabtree Minnie Maddern Fiske Jennie Yeamans Maude Adams Maude Raymond Mary Pickford Fred Stone Effie Shannon 1 Mrs. Charles R. Thorne Sr. Bijou Heron Annie Pixley Continued 230 Appendix Appendix Continued Effie Ellsler Mrs. John Wood Annie Russell Laurette Taylor May West Fay Bainter Eva Topsy Madge Kendall Molly Picon Billie Burke Fanny Herring Deacon Perry Marie St. Clare W. J. LeMoyne Mrs. Thomas Jefferson Little Harry George Shelby Fanny Herring F. F. Mackay Frank Drew Charles R. Thorne Jr. Rachel Booth C. Leslie Allen Simon Legree Phineas Fletcher Barton Hill William Davidge Edwin Adams Charles Wheatleigh Lewis Morrison Frank Mordaunt Frank Losee Odell Williams John L. Sullivan William A. Mestayer Eliza Chloe Agnes Booth Ida Vernon Henrietta Crosman Lucille La Verne Mrs. Frank Chanfrau Nellie Holbrook N o t e s P R E F A C E 1 . George Howard, Eva to Her Papa , Uncle Tom’s Cabin & American Culture . http://utc.iath.virginia.edu {*}. -

Facebook As a Reflection of Race- and Gender-Based Narratives Following the Death of George Floyd

social sciences $€ £ ¥ Article Exceptional Injustice: Facebook as a Reflection of Race- and Gender-Based Narratives Following the Death of George Floyd Patricia J Dixon and Lauren Dundes * Department of Sociology, McDaniel College, 2 College Hill, Westminster, MD 21157, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 16 November 2020; Accepted: 8 December 2020; Published: 15 December 2020 Abstract: Following the death of George Floyd, Facebook posts about the Black Lives Matter movement (BLM) surged, creating the opportunity to examine reactions by race and sex. This study employed a two-part mixed methods approach beginning with an analysis of posts from a single college student’s Facebook newsfeed over a 12-week period, commencing on the date of George Floyd’s death (25 May 2020). A triangulation protocol enhanced exploratory observational–archival Facebook posts with qualitative data from 24 Black and White college students queried about their views of BLM and policing. The Facebook data revealed that White males, who were the least active in posting about BLM, were most likely to criticize BLM protests. They also believed incidents of police brutality were exceptions that tainted an otherwise commendable profession. In contrast, Black individuals commonly saw the case of George Floyd as consistent with a longstanding pattern of injustice that takes an emotional toll, and as an egregious exemplification of racism that calls for indictment of the status quo. The exploratory data in this article also illustrate how even for a cause célèbre, attention on Facebook ebbs over time. This phenomenon obscures the urgency of effecting change, especially for persons whose understanding of racism is influenced by its coverage on social media. -

Boletim De Conjuntura

O Boletim de Conjuntura (BOCA) publica ensaios, artigos de revisão, artigos teóricos e www.revistempíricos,a.ufrr.br/ resenhasboca e vídeos relacionados às temáticas de políticas públicas. O periódico tem como escopo a publicação de trabalhos inéditos e originais, nacionais ou internacionais que versem sobre Políticas Públicas, resultantes de pesquisas científicas e reflexões teóricas e empíricas. Esta revista oferece acesso livre imediato ao seu conteúdo, seguindo o princípio de que disponibilizar gratuitamente o conhecimento científico ao público proporciona maior democratização mundial do conhecimento. BOLETIM DE 132 CONJUNTURA BOCA Ano III | Volume 5 | Nº 13 | Boa Vista | 2021 http://www.ioles.com.br/boca ISSN: 2675-1488 http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4473000 BOLETIM DE CONJUNTURA (BOCA) ano III, vol. 5, n. 13, Boa Vista, 2021 www.revista.ufrr.br/boca THE IMPACT OF THE SLOGAN I CAN’T BREATHE ON THE BLACK LIVES MATTER MOVEMENT: THE ERIC GARNER CASE Maurício Fontana Filho1 Abstract The research reports the death of Eric Garner and explores his circumstances and environment. The goal is to analyze the context with a focus on Eric's killing by the police, as well as how the case developed and gained public outcry. From this initial investigation, it works with the Black Lives Matter movement, its origin, organization and objectives. It analyses the various outlines that Eric's case has taken over the years and his contribution to the movement, with emphasis on police brutality and its progress over the last few years. Finally, it explores this context of death and protest through Philip Zimbardo's total situation theory. -

Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation Within American Tap Dance Performances of The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Brynn Wein Shiovitz 2016 © Copyright by Brynn Wein Shiovitz 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950 by Brynn Wein Shiovitz Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Susan Leigh Foster, Chair Masks in Disguise: Exposing Minstrelsy and Racial Representation within American Tap Dance Performances of the Stage, Screen, and Sound Cartoon, 1900-1950, looks at the many forms of masking at play in three pivotal, yet untheorized, tap dance performances of the twentieth century in order to expose how minstrelsy operates through various forms of masking. The three performances that I examine are: George M. Cohan’s production of Little Johnny ii Jones (1904), Eleanor Powell’s “Tribute to Bill Robinson” in Honolulu (1939), and Terry- Toons’ cartoon, “The Dancing Shoes” (1949). These performances share an obvious move away from the use of blackface makeup within a minstrel context, and a move towards the masked enjoyment in “black culture” as it contributes to the development of a uniquely American form of entertainment. In bringing these three disparate performances into dialogue I illuminate the many ways in which American entertainment has been built upon an Africanist aesthetic at the same time it has generally disparaged the black body. -

“OUTRAGEOUS and OFFENSIVE” Ism and Demanding Police Reform

Vegan Elements Thursday September 24, 2020 T: 582-7800 www.arubatoday.com facebook.com/arubatoday instagram.com/arubatoday Page 8 Aruba’s ONLY English newspaper 1 officer indicted in Breonna Taylor case; not for her death By DYAN LOVAN and PIPER HUDSPETH BLACKBURN Associated Press/Report for America LOUISVILLE, Ky. (AP) — A Kentucky grand jury brought no charges against Louisville police for the killing of Breonna Tay- lor during a drug raid gone wrong, with prosecutors saying Wednesday two of- ficers who fired their weap- ons at the Black woman were justified in using force to protect themselves. The grand jury instead charged fired Officer Brett Hankison with three counts of wanton endangerment for firing into Taylor's neigh- bors' homes during the raid on the night of March 13. The FBI is still investigating potential violations of fed- eral law in the case. Along with the killing of George Floyd in Minneso- ta, Taylor's case became a major touchstone for the nationwide protests that have gripped the nation since May — drawing at- tention to entrenched rac- “OUTRAGEOUS AND OFFENSIVE” ism and demanding police reform. This undated photo provided by Taylor family attorney Sam Aguiar shows Breonna Taylor in Louisville, Ky. Continued on next page Associated Press A2 THURSDAY 24 SEPTEMBER 2020 UP FRONT general, said that the offi- Trump's list to fill a future Su- cers acted in self-defense preme Court vacancy. after Taylor's boyfriend fired Before charges were at them. He added that brought, Hankison was Hankison and the two other fired from the city's police officers who entered Tay- department on June 23.