Ed 127 664 Author Institution Spons Agency Bureau

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'GROCERIES**^' Received Irora Lor Husband

G. W. BLISS. BY MINERAL POINT, WISCONSIN, TUESDAY. JUNE -2. 1857. VOL. X. NO. *2O. , Z o t r n . ■:rl Datnt rilnuu. c ® ;i .v u * i' sti tiiti ili; W- Iki that you S dean, Is .u.i Fir.tn the Oh! a- >. I j the to wnom, su or lab, r :, '* h -- .. - i 'Y service Revising , TL iLBDa\ • ux.d In-, Important the Registry. , . iXOitSINO . untd n j The 1 'l i 1 1 n—sc. on Bxi.icu. Arad ooo.t in Ohio. following ■ ” b might be f' beautiful lines, written by one of a.* due.” . L'U-cii. Third i'lojr, on the Conner - sxjl.de.; o *J aa W e our of or Sl :s a Fill and put . it>.til lid iong since j give up much space in paper ' yraasioa vill.-d i><- -f the hi,- been once before- Cc xo property “Slop. 1 can I'.iuiii.” 'hat aovisi'J our r aders to look iiv to-day to correspondence and c nunurtica- pnh.rshee. in the Jrijv>,e, In , out for . but as it bear reading one of the nort.'u, :i I. w-- * will towns ci ...r- x> BLISb. • ' > •' < —. v . ’■ ii ev.ry week, and “grow “You rirt-:r> t;i.• Surreaie Court ol There is nothing in lions from various quarters and upon va- IKRMS: better by age," our readers will, --; mom lived a young and : ■ Ohio, tins article of roan. Di ~ i we have no doubt, ns for r va l 0., case comp u-r rious suljecis. -

Marriage Nullity ~

„LUCIAN BLAGA” UNIVERSITY OF SIBIU “SIMION BĂRNUŢIU” FACULTY OF LAW DOCTORAL DISSERTATION ~ Marriage Nullity ~ Sumarry Scientific advisor Professor Dr Alexandru Bacaci Doctoral candidate DanAdrian Doţiu SIBIU 2008 1 Chapter 1. General aspects of the institution of marriage nullity 1.1. Introductory concepts Among all judicial acts setting of the existance of the human being, none has a greater importance than those related to marriage. Having a universal character in space and being constant throughout history, the marriage is, at the same time, diverse in geographica space and variable in time. It means even the family origin 1. The Romanian law giver has foreseen by imperative dispozitions the root and formal conditions for entering into a marriage. Being a solemn legal transaction, the marriage cannot be entered into under any conditions. At the same time, the future spouses must present the proof of fulfilling the basic conditions foreseen by the Family Code 2. The check by the registrar of the deeds presented by the future spouses and of eventual opposition to the marriage and the good faith presumption, means, as a principle, warranties of a valid marriage. In spite of these, the law giver has not excluded the possibility of beaching the legal requirements irrespective of the reasons.That is why by the provisions of Articles 1924 Family Code, the law giver has regulated the institution of abolition the marriage if at enterin into marriage the root and form conditions were not fulfilled or there was an impediment 3. In this dissertation we intend to approach the problem of marriage abolition based on the in force laws and doctrines. -

An Access-Dictionary of Internationalist High Tech Latinate English

An Access-Dictionary of Internationalist High Tech Latinate English Excerpted from Word Power, Public Speaking Confidence, and Dictionary-Based Learning, Copyright © 2007 by Robert Oliphant, columnist, Education News Author of The Latin-Old English Glossary in British Museum MS 3376 (Mouton, 1966) and A Piano for Mrs. Cimino (Prentice Hall, 1980) INTRODUCTION Strictly speaking, this is simply a list of technical terms: 30,680 of them presented in an alphabetical sequence of 52 professional subject fields ranging from Aeronautics to Zoology. Practically considered, though, every item on the list can be quickly accessed in the Random House Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary (RHU), updated second edition of 2007, or in its CD – ROM WordGenius® version. So what’s here is actually an in-depth learning tool for mastering the basic vocabularies of what today can fairly be called American-Pronunciation Internationalist High Tech Latinate English. Dictionary authority. This list, by virtue of its dictionary link, has far more authority than a conventional professional-subject glossary, even the one offered online by the University of Maryland Medical Center. American dictionaries, after all, have always assigned their technical terms to professional experts in specific fields, identified those experts in print, and in effect held them responsible for the accuracy and comprehensiveness of each entry. Even more important, the entries themselves offer learners a complete sketch of each target word (headword). Memorization. For professionals, memorization is a basic career requirement. Any physician will tell you how much of it is called for in medical school and how hard it is, thanks to thousands of strange, exotic shapes like <myocardium> that have to be taken apart in the mind and reassembled like pieces of an unpronounceable jigsaw puzzle. -

Memorandum and Articles of Association of Heng Tai Consumables Group Limited 亨泰消費品集團有限公司

MEMORANDUM AND ARTICLES OF ASSOCIATION OF HENG TAI CONSUMABLES GROUP LIMITED 亨泰消費品集團有限公司 This Memorandum and Articles of Association (“M&A”) is a conformed copy or a consolidated version not formally adopted by shareholders at a general meeting. If there is any inconsistency between the English and Chinese versions of this M&A, the English version shall prevail. * The authorised share capital of Heng Tai Consumables Group Limited was consolidated to HK$100,000,000 divided into 1,000,000,000 ordinary shares of par value of HK$0.10 each by ordinary resolution passed at the annual general meeting held on 29 December 2015 and further increased to HK$1,000,000,000 divided into 10,000,000,000 ordinary shares of par value of HK$0.10 each by ordinary resolution passed at the extraordinary general meeting held on 23 November 2016. ASSISTANT SECRETARY’S CERTIFICATE HENG TAI CONSUMABLES GROUP LIMITED 亨泰消費品集團有限公司 Cricket Square, Hutchins Drive P.O. Box 2681 Grand Cayman KY1-1111 Cayman Islands We, Codan Trust Company (Cayman) Limited, Assistant Secretary of HENG TAI CONSUMABLES GROUP LIMITED 亨泰消費品集團有限公司 DO HEREBY CERTIFY that the following is a true extract of ordinary resolutions of the shareholders passed on 23rd November, 2016 and that such resolutions have not been modified. ORDINARY RESOLUTIONS _________________________ Sharon Pierson for and on behalf of Codan Trust Company (Cayman) Limited Assistant Secretary Dated this 24th day of November, 2016 AP_Legal – 102963032.1 Filed: 24-Nov-2016 15:32 EST www.verify.gov.ky File#: 109286 Auth Code: H59622543495 Uploaded: 31-Dec-2015 10:21 EST Filed: 31-Dec-2015 11:50 EST www.verify.gov.ky File#: 109286 Auth Code: K88167744099 MEMORANDUM OF ASSOCIATION OF HENG TAI CONSUMABLES GROUP LIMITED 亨泰消費品集團有限公司 (amended, restated and adopted by the special resolution passed by the shareholders of the Company on 5 December 2011) JLL\612574\4791729v1 THE COMPANIES LAW (2010 REVISION) EXEMPTED COMPANY LIMITED BY SHARES MEMORANDUM OF ASSOCIATION OF Heng Tai Consumables Group Limited 亨泰消費品集團有限公司 1. -

Exhibit a 2015-CFPB-0029 Document 104A Filed 06/03/2016 Page 2 of 48

2015-CFPB-0029 Document 104A Filed 06/03/2016 Page 1 of 48 Exhibit A 2015-CFPB-0029 Document 104A Filed 06/03/2016 Page 2 of 48 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Before the CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECI'ION BUREAU ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEEDING File No. 2015-CFPB-0029 ) ) In the Matter of: ) ) ) DECLARATION OF JOHN ) MARLOW ) INTEGRITY ADVANCE, LLC and ) JAMES R. CARNES, ) ) ) Respondents. ) ) ________________________ ) DECLARATION OF JOHN MARLOW District of Columbia: I, John Marlow, hereby declare and state as follows: 1. My name is John Marlow. I am employed by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) as a paralegal specialist in the CFPB Office of Enforcement in Washington, DC. The following facts are known to me personally and if called as a witness, I would competently testify thereto. 2. As part of my job, I research and investigate people and entities that may be violating the Consumer Financial Protection Act and other statutes enforced by the CFPB. I have been assigned to work on the Bureau's administrative proceeding against Integrity Advance, LLC and James R. Carnes. 2015-CFPB-0029 Document 104A Filed 06/03/2016 Page 3 of 48 3· Attachment 1 to this declaration is a true and correct copy of the Declaration of Nikhil Singhvi in Support of Plaintiff Federal Trade Commission's Motion for Summary Judgment in FTC v. AMG Services Inc., 2:12-cv-00536-GMN-VCF (D. Nev. Sept. 30, 2013), ECF No. 454-2. 4· Attachment 2 to this declaration is a true and correct copy of the FTC's Exhibit 22 that is attached to the Declaration of Nikhil Singhvi in FTC v. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microShn master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in ^pewriter face, while others may be from any type of conq)uter printer. Hie quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the qualiQr of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margin»;, and ingroper alignment can adverse^ affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have beer reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for aiy photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 BUSINESS BEHAVIOR AS A FUNCTION OF BUSINESS STRUCTURE: A TRANSACTION THEORY OF COOPERATIVE FIRMS DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Peter Daniel Goldsmith, B.A., B.S., M.B.A., M.A. -

Ordinary Language Arguments and the Philosophy of Mind

Ordinary Language Arguments and the Philosophy of Mind Submitted by Timb D. Hoswell B. A. Hons A thesis submitted in complete fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Philosophy Faculty of Theology and Philosophy Australian Catholic University Research Services Office 40 Edward Street North Sydney New South Wales 2060 P.O. Box 968 North Sydney, New South Wales, 2059 July 2020 1 To my mother, Elisabeth Moore, who, despite the death of my father, raised me as best she could around the hospitals, psyche wards and nursing homes she worked in, and I spent much of my early years, and to her complete, unapologetic and incorrigible love of medicine and the medical sciences. To Myf. This is what I was doing at the university. With special thanks to Dr John Gerad Quilter, my Pater Philosophici, who fought for this thesis the entire way. Also, many thanks to Louise Clayton-Jones for her patient editing and grammatical notes. With further thanks to Associate Professor Michael Griffith for supporting me and encouraging my originality in something of a guardian spirit role. Dr Edward, ‘Ted’, Sadler for teaching me to be painstakingly thorough in my scholarship and historical research as an undergraduate. Such lessons have stayed with me through my life. To all of my lecturers of past, present and future. Lastly to all of the Philosophy and Theology Department at ACU for all of their support over the years. Thank you. 2 A note on the text Where I introduce an important term either from a philosopher or author, or refer back to that term after a considerable break I use quotation marks. -

Proquest Dissertations

m u Ottawa L'Universite canadienne Canada's university FACULTE DES ETUDES SUPERIEURES FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND ET POSTOCTORALES U Ottawa POSDOCTORAL STUDIES i .'University ciinadicnnc Canada's university Jean-Robert Kibanda Mavita AUTEUR DE LA THESE / AUTHOR OF THESIS Ph.D. (droit canonique) GRADE/DEGREE Department of Economics FACULTE, ECOLE, DEPARTEMENT / FACULTY, SCHOOL, DEPARTMENT La prise de possession canonique et I'exercice de l'office de I'eveque diocesain. Etude du canon 382 § 1 et de ses incidences juridiques TITRE DE LA THESE / TITLE OF THESIS Roch Page DIRECTEUR (DIRECTRICE) DE LA THESE / THESIS SUPERVISOR CO-DIRECTEUR (CO-DIRECTRICE) DE LA THESE / THESIS CO-SUPERVISOR EXAMINATEURS (EXAMINATRICES) DE LA THESE/THESIS EXAMINERS Gary W. Slater Le Doyen de la Faculte des etudes superieures et postdoctorales / Dean of the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies LA PRISE DE POSSESSION CANONIQUE ET L'EXERCICE DE L'OFFICE DE L'EVEQUE DIOCESAIN. ETUDE DU CANON 382 § 1 ET DE SES INCIDENCES JURIDIQUES par Jean-Robert KIBANDA MAVITA These presentee a la Faculte de droit canonique de TUniversite Saint-Paul, Ottawa, Canada, en vue de I'obtention du grade de docteur en droit canonique Ottawa, Canada Universite Saint-Paul 2004 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-59526-8 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-59526-8 -

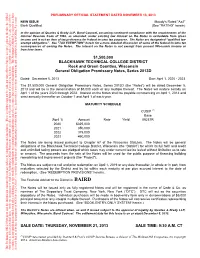

Preliminary Official Statement Dated November 13, 2013

e PRELIMINARY OFFICIAL STATEMENT DATED NOVEMBER 13, 2013 NEW ISSUE Moody’s Rated “Aa2” Bank Qualified (See “RATING” herein) In the opinion of Quarles & Brady LLP, Bond Counsel, assuming continued compliance with the requirements of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended, under existing law interest on the Notes is excludable from gross income and is not an item of tax preference for federal income tax purposes. The Notes are designated “qualified tax- prior to the time the Official exempt obligations”. See "TAX EXEMPTION" herein for a more detailed discussion of some of the federal income tax y Official Statement is in a form consequences of owning the Notes. The interest on the Notes is not exempt from present Wisconsin income or franchise taxes. $1,500,000 BLACKHAWK TECHNICAL COLLEGE DISTRICT Rock and Green Counties, Wisconsin General Obligation Promissory Notes, Series 2013D Dated: December 5, 2013 Due: April 1, 2020 - 2023 fer to buy these securities, nor shall there be any sale of thes The $1,500,000 General Obligation Promissory Notes, Series 2013D (the “Notes”) will be dated December 5, 2013 and will be in the denomination of $5,000 each or any multiple thereof. The Notes will mature serially on ct to revision, amendment, and completion in a Final Official Statement. April 1 of the years 2020 through 2023. Interest on the Notes shall be payable commencing on April 1, 2014 and semi-annually thereafter on October 1 and April 1 of each year. MATURITY SCHEDULE e, but is subje ities may not be sold, nor may offers to buy be accepted, CUSIP (1) Base (April 1) Amount Rate Yield 09237R on under the securities laws of any such jurisdiction. -

Affirmation in Lieu of Oath. Assertory Oath. Decisive Or Decisory Oath

o OASDI. Old Age, Survivors' and Disability Insurance. Extrajudicial oath. One not taken in any judicial See Social Security Administration. proceeding, or without any authority or requirement of law, though taken formally before a proper person. Oath. Any form of attestation by which a person False oath. See False swearing; Perjury. signifies that he is bound in conscience to perform an act faithfully and truthfully, e.g. President's oath on Judicial oath. One taken in some judicial proceeding entering office, Art. II, Sec. 1, U.S.Const. Vaughn v. or in relation to some matter connected with judicial State, 146 Tex.Cr.R. 586, 177 S.W.2d 59, 60. An proceedings. One taken before an officer in open affirmation of truth of a statement, which renders court, as distinguished from a "non-judicial" oath, one willfully asserting untrue statements punishable which is taken before an officer ex parte or out of for perjury. An outward pledge by the person taking court. See also Witnesses, below. it that his attestation or promise is made under an Loyalty oath. An oath requiring one to swear his immediate sense of responsibility to God. A solemn loyalty to the state and country generally as a condi appeal to the Supreme Being in attestation of the tion of public employment. Such oaths which are not truth of some statement. An external pledge or as overbroad have been upheld. Elfbrandt v. Russell, severation, made in verification of statements made, 384 U.S. 11, 86 S.Ct. 1238, 16 L.Ed.2d 321; Cole v. -

Supreme Court of the United States

No. IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES GREGORY STESHENKO -PETITIONER (Your Name) vs. THOMAS MCKAY, et al. -RESPONDENT(S) ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT (NAME OF COURT THAT LAST RULED ON MERITS OF YOUR CASE) PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI Gregory Steshenko - (Your Name) 3030 Mario Court (Address) Aptos, CA 95003 (City, State, Zip Code) (831)531-2254 (Phone Number) QUESTION(S) PRESENTED Whether the mixed-motive defense doctrine of Mt. Healthy City Sch. Dist. Bd. of Educ. v. Doyle, 429 U.S. 274, 287 (1977) in employment terminations for the protected speech is applicable to educational expulsions. Whether the federal court properly obrogated California Education Code through re-definition of what constitutes academic and disciplinary expulsions and what processes should be followed in each case. Whether the court's re-definition of what constitutes academic and disciplinary expulsions violated the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Whether Appellant's rights to due process afforded by the Fourteenth Amendment were violated by his immediate expulsion for his protected speech. Whether declination of the court to impose remedial sanctions for the mass spoliation of the crucial evidence that was sufficient to prove the case violated the due process clauses of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. Whether the party that "prevailed" through spoliation of evidence should be awarded costs. LIST OF PARTIES [ ] All parties appear in the caption of the case on the cover page. v] All parties do not appear in the caption of the case on the cover page. -

A Comparison of the Administrative Law of the Catholic Church and the United States John J

Notre Dame Law School NDLScholarship Journal Articles Publications 2000 A Comparison of the Administrative Law of the Catholic Church and the United States John J. Coughlin Notre Dame Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/law_faculty_scholarship Part of the Administrative Law Commons Recommended Citation John J. Coughlin, A Comparison of the Administrative Law of the Catholic Church and the United States, 34 Loy. L.A. L. Rev. 81 (2000-2001). Available at: https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/law_faculty_scholarship/517 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A COMPARISON OF THE ADMINISTRATIVE LAW OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH AND THE UNITED STATES Rev. John J. Coughlin, O.F.M.* I. INTRODUCTION Some years ago, an international symposium of jurists described administrative law as encompassing the entire range of action by government with respect to the citizen or by the citizen with respect to the government, ex- cept for those matters dealt with by the criminal law, and those left to private civil litigation where the government's only participation is in furnishing an impartial tribunal with the power of enforcement.' The broad parameters of the concept of administrative law attest to its importance in any legal system. Indeed, for at least the past fifty years, comparative legal scholars have focused on diverse na- tional systems of administrative law.2 Canonists have also contrib- * Assistant Professor of Law, St.