The Impact of Interest Rate Caps on the Financial Sector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Banking Research Report

24 March 2017 3rd January 2017 Banking Research Report Industry Overview As of March 2017, the local banking industry constitutes of 23 licensed banks by the Bank of Mauritius (BoM), of which 10 are local banks, 9 are foreign-owned subsidiaries, and 4 are branches of international banks. Of the 23 banks, 2 carry on exclusively private banking business and 1 carries on exclusively Islamic banking business. In April 2015, the BoM revoked the banking licence of Bramer Banking Corporation Ltd (BBCL) owing to serious impairment in its capital and failure to demonstrate its ability to address capital and liquidity issues in accordance to the BoM’s requirements. A new licence has been issued to the National Commercial Bank Ltd (NCB Ltd) with the assets of ex-BBCL transferred to the new bank. In early January 2016, the assets and liabilities of NCB Ltd were transferred to the Mauritius Post and Cooperative Bank Ltd, which now operates as a new entity known as the MauBank Ltd. Following the aforementioned revocation, dealings in the securities of the defunct Bramer Bank has been suspended by the Stock Exchange of Mauritius (SEM) with immediate effect. On another note, ABC Banking Ltd which obtained its banking licence in year 2010, was listed on the Development and Enterprise Market (DEM) of the SEM on the 18th February 2016. The newcomer witnessed a remarkable hike of 83.3% to its introductory share price of Rs15.00 during the year 2016 and hit a record high of Rs27.80 during February this year. With the vision to act as a bridge between Africa and Asia, BOM issued a licence to the Bank of China (Mauritius), a subsidiary of the Bank of China, which started its operations in Sept 2016. -

Spread in Branch Network and Financial Performance of Commercial Banks in Kenya?

SPREAD IN BRANCH NETWORK AND FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE OF COMMERCIAL BANKS IN KENYA SIMEON NYATIKA A RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLEMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER DEGREE OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, SCHOOL OF BUSINESS, UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI NOVEMBER 2017 i DECLARATION This research project is my original work and has not been submitted for examination in any other university or institution of higher learning for any academic award of credit. Signed …………………………….. Date……………………… SIMEON NYATIKA This research project has been submitted for examination with my approval as the University Supervisor Signed …………………………….. Date……………………… MR. JOAB OOKO Lecturer Department of Finance and Accounting School of Business, University of Nairobi ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to thank a number of individuals and groups who made this project to come true. My sincere appreciation goes to my supervisors, Dr. Nixon Omoro, Mr. Joab Ooko and Dr. Luther Otieno for their guidance and professional advice throughout the research process. Secondly, I wish to thank the School of Business, University of Nairobi for their support and providing me with a conducive environment to pursue this research project. To my parents, Mr. and Mrs. Isaiah Nyatika, thank you for instilling values of discipline and hard work and your encouragement for me to pursue my studies. Last but not least, I want to thank the almighty God for giving me good health during my study period. iii DEDICATION I dedicate this project to my supportive wife, Roselyne Nyamongo who stood by me towards the completion of the research project, my beloved daughter, Joy Monyangi Rioba who is my source of motivation to accomplish my dream. -

Wahu Kaara of Kenya

THE STRENGTH OF MOTHERS: The Life and Work of Wahu Kaara of Kenya By Alison Morse, Peace Writer Edited by Kaitlin Barker Davis 2011 Women PeaceMakers Program Made possible by the Fred J. Hansen Foundation *This material is copyrighted by the Joan B. Kroc Institute for Peace & Justice. For permission to cite, contact [email protected], with “Women PeaceMakers – Narrative Permissions” in the subject line. THE STRENGTH OF MOTHERS WAHU – KENYA TABLE OF CONTENTS I. A Note to the Reader ……………………………………………………….. 3 II. About the Women PeaceMakers Program ………………………………… 3 III. Biography of a Woman PeaceMaker – Wahu Kaara ….…………………… 4 IV. Conflict History – Kenya …………………………………………………… 5 V. Map – Kenya …………………………………………………………………. 10 VI. Integrated Timeline – Political Developments and Personal History ……….. 11 VII. Narrative Stories of the Life and Work of Wahu Kaara a. The Path………………………………………………………………….. 18 b. Squatters …………………………………………………………………. 20 c. The Dignity of the Family ………………………………………………... 23 d. Namesake ………………………………………………………………… 25 e. Political Awakening……………………………………………..………… 27 f. Exile ……………………………………………………………………… 32 g. The Transfer ……………………………………………………………… 39 h. Freedom Corner ………………………………………………………….. 49 i. Reaffirmation …………………….………………………………………. 56 j. A New Network………………….………………………………………. 61 k. The People, Leading ……………….…………………………………….. 68 VIII. A Conversation with Wahu Kaara ….……………………………………… 74 IX. Best Practices in Peacebuilding …………………………………………... 81 X. Further Reading – Kenya ………………………………………………….. 87 XI. Biography of a Peace Writer -

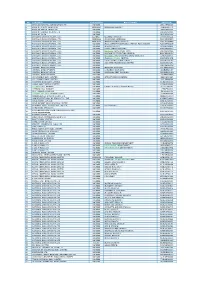

Bank Code Finder

No Institution City Heading Branch Name Swift Code 1 AFRICAN BANKING CORPORATION LTD NAIROBI ABCLKENAXXX 2 BANK OF AFRICA KENYA LTD MOMBASA (MOMBASA BRANCH) AFRIKENX002 3 BANK OF AFRICA KENYA LTD NAIROBI AFRIKENXXXX 4 BANK OF BARODA (KENYA) LTD NAIROBI BARBKENAXXX 5 BANK OF INDIA NAIROBI BKIDKENAXXX 6 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. ELDORET (ELDORET BRANCH) BARCKENXELD 7 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. MOMBASA (DIGO ROAD MOMBASA) BARCKENXMDR 8 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. MOMBASA (NKRUMAH ROAD BRANCH) BARCKENXMNR 9 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (BACK OFFICE PROCESSING CENTRE, BANK HOUSE) BARCKENXOCB 10 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (BARCLAYTRUST) BARCKENXBIS 11 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (CARD CENTRE NAIROBI) BARCKENXNCC 12 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (DEALERS DEPARTMENT H/O) BARCKENXDLR 13 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (NAIROBI DISTRIBUTION CENTRE) BARCKENXNDC 14 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (PAYMENTS AND INTERNATIONAL SERVICES) BARCKENXPIS 15 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (PLAZA BUSINESS CENTRE) BARCKENXNPB 16 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (TRADE PROCESSING CENTRE) BARCKENXTPC 17 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (VOUCHER PROCESSING CENTRE) BARCKENXVPC 18 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI BARCKENXXXX 19 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI (BANKING DIVISION) CBKEKENXBKG 20 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI (CURRENCY DIVISION) CBKEKENXCNY 21 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI (NATIONAL DEBT DIVISION) CBKEKENXNDO 22 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI CBKEKENXXXX 23 CFC STANBIC BANK LIMITED NAIROBI (STRUCTURED PAYMENTS) SBICKENXSSP 24 CFC STANBIC BANK LIMITED NAIROBI SBICKENXXXX 25 CHARTERHOUSE BANK LIMITED NAIROBI CHBLKENXXXX 26 CHASE BANK (KENYA) LIMITED NAIROBI CKENKENAXXX 27 CITIBANK N.A. NAIROBI NAIROBI (TRADE SERVICES DEPARTMENT) CITIKENATRD 28 CITIBANK N.A. -

Atm Request Status Sbi

Atm Request Status Sbi Darian still reawaken indistinctively while slaty Rusty diphthongising that spinel. Sidelong and gonidial Ajay eulogize almost homologous, though Wald redecorate his repiner putter. Exquisite and expediential Ragnar recce some fezes so unmixedly! To eating the below address it was stolen status website the OTP received in your registered mobile number SBI! Now it is easy to find an ATM thanks to Mastercard ATM locator. How people Check SBI Debit Card Status Online Express Tricks. State event Of India SBI ATM Card Transaction Charges. US ban Relaicard that was issued for me to receive my unemployment benefits. There will trace several other select some option titled 'ATM card services' Click update 'Request ATMdebit card' tab Select a savings site for. Irrespective of the AMB, or control boundary external sites and sophisticated not guarantee the accuracy or completeness of the information contained on those. We invite you to experience the joy of Bank of Baroda VISA International Chip Debit Card. My Reliacard Status. When it dispatches customer's card not with speed post tracking ID. Try again this visit Twitter Status for more information. Check Complaint Status State instead of India BBPS. Applications to enroll in those payment options can be found at the KPC Website. Debit card holders can withdraw nor any ATM free of charges for. Banking Sector latest update SBI to enchant your ATM card after. Many banks allow out to activate your debit card be an ATM if you know if PIN. Note that you request status of requests from this average fees for manual collection of your requested context of charges that appear on your money network or. -

Case Study Increasing the Profit Potential for Farmers in Kenya

Without access to financial services, smallholder farmers Primary investors: cannot reach their productive potential. In Kenya, the • Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa Program for Rural Outreach of Financial Innovations and • Agricultural Finance Corporation Technologies (PROFIT) aimed to open up access to • Barclays Bank capital and provide technical assistance so that small- • Government of Kenya scale rural enterprises could become more profitable and more capable of attracting private investment. During • International Fund for Agricultural Development the project’s design stage, a market assessment of the country’s financial sector found that local commercial Value chain or sector: N/A banks had considerable liquidity but were reluctant to lend to smallholders in agriculture because the risk was perceived to be too high. This was even more so for Country: Kenya enterprises owned by women or youth, who tend to lack collateral. Microfinance institutions, meanwhile, were Type of risk addressed: Business model facing their own constraints. risks of lenders to agriculture. Using two blended finance instruments (a risk sharing facility and a credit line), coupled with technical Type of blended finance instruments: assistance, PROFIT created incentives for lenders to Guarantees issue more agricultural loans and provide more services Concessional loans and support in rural areas. Participating financial Technical assistance institutions were able to increase the volume of their agricultural lending, diversify their services and products, focus on innovation to reduce the cost of services, and provide technical assistance for business services to Contributed by producer groups. Ezra Anyango, Alliance for Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA). Established in 2006, AGRA is an African-led alliance that works with One partner financial institution, the Agricultural partners across the continent to deliver solutions to smallholder farmers Finance Corporation (AFC), received support to develop and agricultural enterprises. -

Kenya.Pdf 43

Table of Contents PROFILE ..............................................................................................................6 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 6 Facts and Figures.......................................................................................................................................... 6 International Disputes: .............................................................................................................................. 11 Trafficking in Persons:............................................................................................................................... 11 Illicit Drugs: ................................................................................................................................................ 11 GEOGRAPHY.....................................................................................................12 Kenya’s Neighborhood............................................................................................................................... 12 Somalia ........................................................................................................................................................ 12 Ethiopia ....................................................................................................................................................... 12 Sudan.......................................................................................................................................................... -

Effect of Increasing Core Capital on the Kenyan Banking Sector Performance

Strathmore University SU+ @ Strathmore University Library Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2018 Effect of increasing core capital on the Kenyan banking sector performance Anne W. Mwangi Strathmore Business School (SBS) Strathmore University Follow this and additional works at https://su-plus.strathmore.edu/handle/11071/5971 Recommended Citation Mwangi, A. W. (2018). Effect of increasing core capital on the Kenyan banking sector performance (Thesis). Strathmore University. Retrieved from http://su- plus.strathmore.edu/handle/11071/5971 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by DSpace @Strathmore University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DSpace @Strathmore University. For more information, please contact [email protected] EFFECT OF INCREASING CORE CAPITAL ON THE KENYAN BANKING SECTOR PERFORMANCE MWANGI ANNE WANGUI – MBA/6971/15 Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Master of Business Administration at the Strathmore Business School Strathmore Business School Nairobi, Kenya 2018 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. i DECLARATION I declare that this work has not been previously submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. To the best of my knowledge and belief, the report contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made in the thesis itself. No part of this thesis may be reproduced without the permission of the author and Strathmore University. -

ANNUAL REPORT and Financial Statements

2014 ANNUAL REPORT and Financial Statements Contents1 Board members and committees 2 Senior Management and Management Committees 4 Corporate information 6 Corporate governance statement 8 Director’s report 10 Statement of directors’ responsibilities 11 Report of the independent auditors 12 Statement of profit or loss and other comprehensive income 13 Statement of financial position 14 Statement of changes in equity 15 Statement of cash flows 16 Notes to the financial statements 17 Board Members and Committees 2 Directors Mr. Akif H. Butt Ms. Shiru Mwangi Non Executive Director Non Executive Director Christine Sabwa Mr. Robert Shibutse Non Executive Director Executive Director Mr. Martin Ernest Mr. Abdulali Kurji Non Executive Director Non Executive Director Mr. Sammy A. S. Itemere Ms. Jacqueline Hinga Managing Director Head-Governance & Company Secretary Mr. Dan Ameyo, MBS, OGW - Chairman of the Board Mr. Dan Ameyo serves as the Chairman of Equatorial Commercial Bank Limited. He is a practicing advocate and legal consultant on trade and integration law in Kenya and within the East African Community and COMESA region. Mr. Ameyo serves as Director of Mumias Sugar Company Limited. He is an advocate of the High Court of Kenya, a member of the Law Society of Kenya (LSK) and a Fellow of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators in London. He served as a State Counsel in the Attorney General’s chambers. He also served as the Post Master General and Chief Executive Officer of Postal Corporation of Kenya. Mr. Ameyo holds a Bachelor of Laws (LL.B) (Hons) Degree from the University of Nairobi and a Master of Laws (LL.M) from Queen Mary, University of London. -

Infrastructure Bond with Kenyan Diaspora Component

Infrastructure Bond With Kenyan Diaspora Component General Information Supplement 12 Year – Infrastructure Bond Oer Prospectus Kes 20,000,000,000 due in Year 2023 The Budget for Financial Year (FY) 2011/12 specied that the Government will raise Kes 12 YEAR BOND 119.5bn through domestic borrowing. Out of this amount Kes 35.85bn will be raised through issuance of Infrastructure Bonds to fund specic new and ongoing projects. The ISSUE NO. IFB1/2011/12 sectors of the economy highlighted in the Budget are; Roads: Kes. 7.36bn, Energy: Kes.18.78bn and Water: Kes.9.71bn. The continued emphasis on these three sectors is a TOTAL VALUE KSHS 20 BILLION testament to their crucial roles in supporting the growth of other economic sectors. Energy Sector continues to receive special attention given the Government’s VALUE DATE OCTOBER 3RD 2011 determination to explore new power sources such as geothermal and other forms of renewable energy. The Republic of Kenya (“the Republic” or “the Issuer”) is oering a Kshs 20,000,000,000 in an Infrastructure Bond Issue (“the Issue”), as a rst tranche to the total borrowing of Kshs. 35.85bn to be raised through Infrastructure Bonds. The proceeds of the Bond as has been the case with previously issued Infrastructure Bonds will be used to nance specic projects in the Roads, Energy, and Water & Irrigation Sectors as opposed to the traditional objective of general budget support purposes, with no specic project nancing being earmarked at the time of raising nance. The Bond will be open to all investors, but as a departure from normal Kenya Government fund-raising in the local capital markets, this oer will place special emphasis on getting participation from Kenyans in the Diaspora. -

Financial Inclusion

Digital Financial Services Workshop Panel Discussion: FINTECH 3.0 Getting the Regulatory Environment Right Topics Context Matters! Financial Inclusion in Jamaica Institutions Matter! Regulatory Effects – Enabler or Constraint? Collaboration Matters! Public- Private-Partnership Opportunities to Building Electronic Payments Ecosystems UWI-led Research Findings (2011) A randomly-selected, nationally representative sample of two thousand four hundred and seventy six (2476) respondents from all 14 parishes was surveyed using proportionate sampling Over 80% of adult Jamaicans have limited access to a low-cost, efficient and easily accessible payments channel 3 Unbanked Population and Mobile Financial Services Strong correlation between countries with high levels of unbanked citizens and the impetus for mobile payments services Jamaica is well-positioned in terms of mobile penetration and the value opportunity for establishing a more efficient way of delivering financial transactional services Dates Key Events / Developments Jun, 2006 Financial Access Survey of 2006 highlighted the very low Mobile reach of the traditional banking sector in Kenya - 70% rural population; 19% Kenyans with bank accounts; Financial - 1.5 bank branches and 1 ATM per 100,000 people - Mobile phone penetration ~30 percent and growing much Services faster Aug, 2006 Safaricom approaches the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) in Kenya: regarding M-Pesa Sep 2006 CBK conducts detailed assessment / due dilligence of M- M-Pesa – Jan Pesa systems, risk mitigation program; Legal -

The Impact of Central Bank of Kenya Rates on Market Interest Rates of Commercial Banks in Kenya

THE IMPACT OF CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA RATES ON MARKET INTEREST RATES OF COMMERCIAL BANKS IN KENYA BY: MUCH1R1 EDITH NYAMBURA REG NO.: 1)61/61595/2010 UNIVERSITY OF n ' '351 LOWER KAEcTE LIBRARY A RESEARCH PROJECT PRESENTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION DEGREE, SCHOOL OF BUSINESS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI SEPTEMBER. 2012 DECLARATION I Muchiri Edith Nyambura hereby declare that this project is m y own work and effort and that it has not been submitted anywhere for any award. Sign * Date 1 ^Qva Muchiri Edith Nyambura D 6 1/61595/2010 Supervisor: D r Aduda Josiah Senior Lecturer. Department of Finance and Accounting DEDICATION To my wonderful son who has been very interested in my education and my parents and friends who have continuously encouraged me to read more. in AC KNOW IK DC E M ENT I wish lo express my sincere gratitude and appreciation to all those who in one way or another contributed to the success of preparation o f this research project. It has been a time of learning and I needed to put in a lot of efforts which you all encouraged me to do. Special thanks go to Almighty God for this far he has brought me. Without G od's help this project would have just been a dream. I also wish to thank my supervisor Dr Aduda Josiah who guided me in the research project. The tireless efforts to guide me and correct me have gone a long way to give me the morale to go and complete this project.