Effect of Increasing Core Capital on the Kenyan Banking Sector Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spread in Branch Network and Financial Performance of Commercial Banks in Kenya?

SPREAD IN BRANCH NETWORK AND FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE OF COMMERCIAL BANKS IN KENYA SIMEON NYATIKA A RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLEMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER DEGREE OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, SCHOOL OF BUSINESS, UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI NOVEMBER 2017 i DECLARATION This research project is my original work and has not been submitted for examination in any other university or institution of higher learning for any academic award of credit. Signed …………………………….. Date……………………… SIMEON NYATIKA This research project has been submitted for examination with my approval as the University Supervisor Signed …………………………….. Date……………………… MR. JOAB OOKO Lecturer Department of Finance and Accounting School of Business, University of Nairobi ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to thank a number of individuals and groups who made this project to come true. My sincere appreciation goes to my supervisors, Dr. Nixon Omoro, Mr. Joab Ooko and Dr. Luther Otieno for their guidance and professional advice throughout the research process. Secondly, I wish to thank the School of Business, University of Nairobi for their support and providing me with a conducive environment to pursue this research project. To my parents, Mr. and Mrs. Isaiah Nyatika, thank you for instilling values of discipline and hard work and your encouragement for me to pursue my studies. Last but not least, I want to thank the almighty God for giving me good health during my study period. iii DEDICATION I dedicate this project to my supportive wife, Roselyne Nyamongo who stood by me towards the completion of the research project, my beloved daughter, Joy Monyangi Rioba who is my source of motivation to accomplish my dream. -

Bank Code Finder

No Institution City Heading Branch Name Swift Code 1 AFRICAN BANKING CORPORATION LTD NAIROBI ABCLKENAXXX 2 BANK OF AFRICA KENYA LTD MOMBASA (MOMBASA BRANCH) AFRIKENX002 3 BANK OF AFRICA KENYA LTD NAIROBI AFRIKENXXXX 4 BANK OF BARODA (KENYA) LTD NAIROBI BARBKENAXXX 5 BANK OF INDIA NAIROBI BKIDKENAXXX 6 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. ELDORET (ELDORET BRANCH) BARCKENXELD 7 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. MOMBASA (DIGO ROAD MOMBASA) BARCKENXMDR 8 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. MOMBASA (NKRUMAH ROAD BRANCH) BARCKENXMNR 9 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (BACK OFFICE PROCESSING CENTRE, BANK HOUSE) BARCKENXOCB 10 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (BARCLAYTRUST) BARCKENXBIS 11 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (CARD CENTRE NAIROBI) BARCKENXNCC 12 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (DEALERS DEPARTMENT H/O) BARCKENXDLR 13 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (NAIROBI DISTRIBUTION CENTRE) BARCKENXNDC 14 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (PAYMENTS AND INTERNATIONAL SERVICES) BARCKENXPIS 15 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (PLAZA BUSINESS CENTRE) BARCKENXNPB 16 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (TRADE PROCESSING CENTRE) BARCKENXTPC 17 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI (VOUCHER PROCESSING CENTRE) BARCKENXVPC 18 BARCLAYS BANK OF KENYA, LTD. NAIROBI BARCKENXXXX 19 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI (BANKING DIVISION) CBKEKENXBKG 20 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI (CURRENCY DIVISION) CBKEKENXCNY 21 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI (NATIONAL DEBT DIVISION) CBKEKENXNDO 22 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA NAIROBI CBKEKENXXXX 23 CFC STANBIC BANK LIMITED NAIROBI (STRUCTURED PAYMENTS) SBICKENXSSP 24 CFC STANBIC BANK LIMITED NAIROBI SBICKENXXXX 25 CHARTERHOUSE BANK LIMITED NAIROBI CHBLKENXXXX 26 CHASE BANK (KENYA) LIMITED NAIROBI CKENKENAXXX 27 CITIBANK N.A. NAIROBI NAIROBI (TRADE SERVICES DEPARTMENT) CITIKENATRD 28 CITIBANK N.A. -

Commercial Banks Directory As at 30Th April 2006

DIRECTORY OF COMMERCIAL BANKS AND MORTGAGE FINANCE COMPANIES A: COMMERCIAL BANKS African Banking Corporation Ltd. Postal Address: P.O Box 46452-00100, Nairobi Telephone: +254-20- 4263000, 2223922, 22251540/1, 217856/7/8. Fax: +254-20-2222437 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.abcthebank.com Physical Address: ABC Bank House, Mezzanine Floor, Koinange Street. Date Licensed: 5/1/1984 Peer Group: Small Branches: 10 Bank of Africa Kenya Ltd. Postal Address: P. O. Box 69562-00400 Nairobi Telephone: +254-20- 3275000, 2211175, 3275200 Fax: +254-20-2211477 Email: [email protected] Website: www.boakenya.com Physical Address: Re-Insurance Plaza, Ground Floor, Taifa Rd. Date Licenced: 1980 Peer Group: Medium Branches: 18 Bank of Baroda (K) Ltd. Postal Address: P. O Box 30033 – 00100 Nairobi Telephone: +254-20-2248402/12, 2226416, 2220575, 2227869 Fax: +254-20-316070 Email: [email protected] Website: www.bankofbarodakenya.com Physical Address: Baroda House, Koinange Street Date Licenced: 7/1/1953 Peer Group: Medium Branches: 11 Bank of India Postal Address: P. O. Box 30246 - 00100 Nairobi Telephone: +254-20-2221414 /5 /6 /7, 0734636737, 0720306707 Fax: +254-20-2221417 Email: [email protected] Website: www.bankofindia.com Physical Address: Bank of India Building, Kenyatta Avenue. Date Licenced: 6/5/1953 Peer Group: Medium Branches: 5 1 Barclays Bank of Kenya Ltd. Postal Address: P. O. Box 30120 – 00100, Nairobi Telephone: +254-20- 3267000, 313365/9, 2241264-9, 313405, Fax: +254-20-2213915 Email: [email protected] Website: www.barclayskenya.co.ke Physical Address: Barclays Plaza, Loita Street. Date Licenced: 6/5/1953 Peer Group: Large Branches: 103 , Sales Centers - 12 CFC Stanbic Bank Ltd. -

ANNUAL REPORT and Financial Statements

2014 ANNUAL REPORT and Financial Statements Contents1 Board members and committees 2 Senior Management and Management Committees 4 Corporate information 6 Corporate governance statement 8 Director’s report 10 Statement of directors’ responsibilities 11 Report of the independent auditors 12 Statement of profit or loss and other comprehensive income 13 Statement of financial position 14 Statement of changes in equity 15 Statement of cash flows 16 Notes to the financial statements 17 Board Members and Committees 2 Directors Mr. Akif H. Butt Ms. Shiru Mwangi Non Executive Director Non Executive Director Christine Sabwa Mr. Robert Shibutse Non Executive Director Executive Director Mr. Martin Ernest Mr. Abdulali Kurji Non Executive Director Non Executive Director Mr. Sammy A. S. Itemere Ms. Jacqueline Hinga Managing Director Head-Governance & Company Secretary Mr. Dan Ameyo, MBS, OGW - Chairman of the Board Mr. Dan Ameyo serves as the Chairman of Equatorial Commercial Bank Limited. He is a practicing advocate and legal consultant on trade and integration law in Kenya and within the East African Community and COMESA region. Mr. Ameyo serves as Director of Mumias Sugar Company Limited. He is an advocate of the High Court of Kenya, a member of the Law Society of Kenya (LSK) and a Fellow of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators in London. He served as a State Counsel in the Attorney General’s chambers. He also served as the Post Master General and Chief Executive Officer of Postal Corporation of Kenya. Mr. Ameyo holds a Bachelor of Laws (LL.B) (Hons) Degree from the University of Nairobi and a Master of Laws (LL.M) from Queen Mary, University of London. -

General Terms & Conditions Form

General Terms & Conditions Form The relationship between the Bank and the Customer depends upon whether the Customer’s Account is in debit or in credit. Subject to any agreement made in writing between the Bank and the Customer, the relationship between the Bank and the Customer will be governed by the following terms and conditions (the “Terms and Conditions”): 1. DEFINITIONS AND TERMS 5. CUSTOMER’S INSTRUCTIONS • “Account” means any type of account and (including without limitation) in relation • the Bank shall only act on Customer’s original signed instructions or documents drawn to any advance, deposit, contract, product, dealing or service established and operated or accepted in accordance with the Mandate until such time as the Customer shall between the Bank and the Customer; give the Bank written notice to the contrary; • “Available Balance” means the amount (excluding any unconfirmed credit) in the • Instructions received after Banking Hours or on a non-Business Day will be processed Account, which can be drawn by the Customer; on the next Business Day. The customer may cancel instructions which the Bank has • “Application Form” means the Customer or in relation to the Customer in respect to the confirmed in writing that have not been acted upon. This will not be applicable where opening of an Account; the Bank is irrevocably bound to process the transaction in question. The Bank is • “Authorized Signatory” means the Customer or in relation to the Customer any entitled to levy a charge for cancelling instructions; person(s) authorized as specified in writing by the Customer to operate the Account on • the Bank may, subject to certain requirements and upon prior written request from the Customer’s behalf; the Customer, act upon telephonic facsimile, electronic or other forms of non-written • “Bank” means Spire Bank Limited, incorporated in Kenya as a limited liability company communication. -

2 Giro Commercial Bank Ltd Was Acquired by I&M Bank Limited

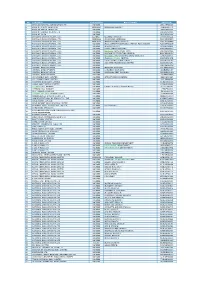

COMMERCIAL BANKS WEIGHTED AVERAGE LENDING RATES PER LOAN CATEGORY AND MATURITY (%) Loan Category PERSONAL BUSINESS CORPORATE OVERALL RATES Loan Maturity Overdraft 1-5 Years Over 5 years Overdraft 1-5 Years Over 5 years Overdraft 1-5 Years Over 5 years 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 Banks Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 Dec-16 Mar-171 Jun-171 1 Africa Banking Corporation Ltd 14.1 13.5 13.1 14.0 13.1 13.7 13.9 13.7 13.9 14.2 12.8 13.7 14.1 13.2 13.8 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.3 13.5 13.7 14.1 12.0 13.70 14.0 13.3 13.7 14.1 13.1 13.7 2 Bank of Africa Kenya Ltd 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.9 13.9 13.9 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.9 13.9 13.9 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.8 14.0 14.0 13.8 13.8 13.75 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.9 13.9 13.9 3 Bank of Baroda (K) Ltd 14.0 13.8 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.9 13.9 13.9 13.9 13.9 13.9 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.9 13.9 13.9 13.9 13.9 13.93 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.9 13.9 13.9 4 Bank of India 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.00 14.0 14.0 13.9 14.0 14.0 14.0 5 Barclays Bank of Kenya Ltd 14.0 14.0 13.5 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.8 13.4 13.5 14.0 13.8 13.9 13.8 13.4 13.7 13.7 13.6 12.7 13.4 13.3 13.33 13.6 13.4 13.5 13.8 13.7 13.8 6 Stanbic Bank Kenya Ltd 13.9 13.8 10.3 13.9 13.8 13.6 13.9 13.9 13.6 12.6 13.7 10.2 13.9 13.9 13.4 13.7 13.8 13.9 12.3 12.7 10.3 13.3 13.3 13.97 14.0 14.0 14.0 13.3 13.6 -

Automated Clearing House Participants Bank / Branches Report

Automated Clearing House Participants Bank / Branches Report 21/06/2017 Bank: 01 Kenya Commercial Bank Limited (Clearing centre: 01) Branch code Branch name 091 Eastleigh 092 KCB CPC 094 Head Office 095 Wote 096 Head Office Finance 100 Moi Avenue Nairobi 101 Kipande House 102 Treasury Sq Mombasa 103 Nakuru 104 Kicc 105 Kisumu 106 Kericho 107 Tom Mboya 108 Thika 109 Eldoret 110 Kakamega 111 Kilindini Mombasa 112 Nyeri 113 Industrial Area Nairobi 114 River Road 115 Muranga 116 Embu 117 Kangema 119 Kiambu 120 Karatina 121 Siaya 122 Nyahururu 123 Meru 124 Mumias 125 Nanyuki 127 Moyale 129 Kikuyu 130 Tala 131 Kajiado 133 KCB Custody services 134 Matuu 135 Kitui 136 Mvita 137 Jogoo Rd Nairobi 139 Card Centre Page 1 of 42 Bank / Branches Report 21/06/2017 140 Marsabit 141 Sarit Centre 142 Loitokitok 143 Nandi Hills 144 Lodwar 145 Un Gigiri 146 Hola 147 Ruiru 148 Mwingi 149 Kitale 150 Mandera 151 Kapenguria 152 Kabarnet 153 Wajir 154 Maralal 155 Limuru 157 Ukunda 158 Iten 159 Gilgil 161 Ongata Rongai 162 Kitengela 163 Eldama Ravine 164 Kibwezi 166 Kapsabet 167 University Way 168 KCB Eldoret West 169 Garissa 173 Lamu 174 Kilifi 175 Milimani 176 Nyamira 177 Mukuruweini 180 Village Market 181 Bomet 183 Mbale 184 Narok 185 Othaya 186 Voi 188 Webuye 189 Sotik 190 Naivasha 191 Kisii 192 Migori 193 Githunguri Page 2 of 42 Bank / Branches Report 21/06/2017 194 Machakos 195 Kerugoya 196 Chuka 197 Bungoma 198 Wundanyi 199 Malindi 201 Capital Hill 202 Karen 203 Lokichogio 204 Gateway Msa Road 205 Buruburu 206 Chogoria 207 Kangare 208 Kianyaga 209 Nkubu 210 -

Bank Supervision Annual Report 2019 1 Table of Contents

CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA BANK SUPERVISION ANNUAL REPORT 2019 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS VISION STATEMENT VII THE BANK’S MISSION VII MISSION OF BANK SUPERVISION DEPARTMENT VII THE BANK’S CORE VALUES VII GOVERNOR’S MESSAGE IX FOREWORD BY DIRECTOR, BANK SUPERVISION X EXECUTIVE SUMMARY XII CHAPTER ONE STRUCTURE OF THE BANKING SECTOR 1.1 The Banking Sector 2 1.2 Ownership and Asset Base of Commercial Banks 4 1.3 Distribution of Commercial Banks Branches 5 1.4 Commercial Banks Market Share Analysis 5 1.5 Automated Teller Machines (ATMs) 7 1.6 Asset Base of Microfinance Banks 7 1.7 Microfinance Banks Market Share Analysis 9 1.8 Distribution of Foreign Exchange Bureaus 11 CHAPTER TWO DEVELOPMENTS IN THE BANKING SECTOR 2.1 Introduction 13 2.2 Banking Sector Charter 13 2.3 Demonetization 13 2.4 Legal and Regulatory Framework 13 2.5 Consolidations, Mergers and Acquisitions, New Entrants 13 2.6 Medium, Small and Micro-Enterprises (MSME) Support 14 2.7 Developments in Information and Communication Technology 14 2.8 Mobile Phone Financial Services 22 2.9 New Products 23 2.10 Operations of Representative Offices of Authorized Foreign Financial Institutions 23 2.11 Surveys 2019 24 2.12 Innovative MSME Products by Banks 27 2.13 Employment Trend in the Banking Sector 27 2.14 Future Outlook 28 CENTRAL BANK OF KENYA 2 BANK SUPERVISION ANNUAL REPORT 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER THREE MACROECONOMIC CONDITIONS AND BANKING SECTOR PERFORMANCE 3.1 Global Economic Conditions 30 3.2 Regional Economy 31 3.3 Domestic Economy 31 3.4 Inflation 33 3.5 Exchange Rates 33 3.6 Interest -

The Effect of Profitability on Dividend Policy Of

THE EFFECT OF PROFITABILITY ON DIVIDEND POLICY OF COMMERCIAL BANKS IN KENYA ELIZABETH WARWARE MIGWI A RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, SCHOOL OF BUSINESS, UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI NOVEMBER, 2015 DECLARATION This research project is my original work and has not been submitted for examination in any other university. ……………………………………. ……………………………. Signature Date Elizabeth Warware Migwi Reg. No D61/65363/2013 Supervisor This research project has been submitted with my approval for examination to the university, as a university supervisor …………………………………… …………………………… Signature Date Dr. Mirie Mwangi Senior Lecturer, Department of Finance and Accounting University of Nairobi ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I am deeply obliged to my supervisor Dr. Mirie Mwangi for his exemplary guidance and support whose help made this research project a success. I thank him for his patience and time during the whole interaction. I wish you God‟s blessings as you continue to make a contribution in the advancement of knowledge in this field. I acknowledge my colleagues for their unwavering support encouragement and understanding and availing time to listen to me when I sought their assistance. I appreciate the department of finance and accounting staff who were always willing to accord me attention whenever necessary. To the University of Nairobi library personnel, I highly appreciate your tireless effort to ensure that the students access the required learning materials at the right time. May the almighty God bless you in your endeavors to assist learners‟ to access information. I take this opportunity to express my deep gratitude to my loving children for their love and moral support and motivation without whom this undertaking would have been a big challenge. -

Victor Ombuna

Investor Presentation 9 April 2019 1 Page 1 Table of Contents Part 1: Introduction to I&M Holdings Group Part 2: 2018 The Year in Perspective Part 3: Subsidiary Performance Part 4: Appendices 2 Page 2 Part 1: Introduction to I&M Holdings Group 3 I&M Holdings PLC Introduction • I&M Holdings Plc, formerly known as City Trust Limited (CTL) was incorporated on 16th August 1950; one of the oldest companies to list on the Nairobi Securities Exchange (NSE). • I&M Holdings was licensed and approved as a non-operating holding company in June 2013 following a reverse takeover of CTL by I&M Bank Limited • The Company is regulated by the Capital Markets Authority (CMA) and the Central Bank of Kenya. • I&M Holdings operates in five countries – Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda, Uganda and Mauritius through its subsidiaries, affiliates and joint venture investments in each of these countries. • The Group is also supported by several development finance institutions, including, CDC Group Plc, Proparco, DEG, FMO, IFC, EIB and ResponsAbility who have over time supported the growth of the Group. CDC Group plc is a significant shareholder, having acquired its shareholding of 10.13% from Proparco and DEG following the completion of the latter’s investment tenor in September 2016. 4 I&M Holdings PLC (IMHP) Group Structure 5 I&M Holdings Plc Board of Directors Mr Daniel Ndonye Mr Suresh B R Shah, MBS Chairman Non-Executive Director Independent Non Executive Director Mr MichaelTurner Dr. Nyambura Koigi Mr Sarit S. RajaShah Independent Non- Independent Non- Group Executive Executive Director Executive Director Director Mr Sachit Shah Mr Oliver Fowler Mr SuleimanKiggundu Jr. -

5D133fa94169cproject-Giro Circular

THIS DOCUMENT IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION to the stockbroker, investment bank or other agent through whom you disposed of your shares. This Circular is issued by I&M Holdings Limited and has been prepared in compliance with the requirements of the Capital Regulations, 2002 and the Nairobi Securities Exchange Listing Manual, 2002. Approval has been obtained from the Capital Markets Authority (“CMA”) in respect of the compliance of this Circular and in this Circular in accordance with the provisions of the Capital Markets Act and other applicable regulations. As a matter of policy, the CMA assumes no responsibility for the correctness of any statements or opinions made or reports contained in this Circular. Approval of the Circular by the CMA is not to be taken as an indication of the merits of the Listing or as a recommendation by CMA to the shareholders of IMHL. the Main Investment Market Segment (MIMS) of the NSE. I&M HOLDINGS LIMITED Incorporated in Kenya under the Companies Act (chapter 486 of the Laws of Kenya) (Registration Number No. C. 7/50) Circular to Shareholders Proposed allotment and issue of 21,043,330 new ordinary shares of the Company as part consideration in exchange for the acquisition of all the issued shares in the capital of Giro Commercial Bank Limited A Notice of an Extraordinary General Meeting of the Company which is to be held on June 27, 2016 at Hotel Sarova Panafric Nairobi, Kenya is set out at the end of this document. A form of proxy for use by shareholders is also enclosed. -

Kisumu County Integrated Development Plan Ii, 2018-2022

KISUMU COUNTY INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN II, 2018-2022 Vision: A peaceful and prosperous County where all citizens enjoy a high- quality life and a sense of belonging. Mission: To realize the full potential of devolution and meet the development aspirations of the people of Kisumu County i Kisumu County Integrated Development Plan | 2018 – 2022 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ...................................................................................................... II LIST OF TABLES.............................................................................................................. VII LIST OF MAPS/FIGURES ................................................................................................... X LIST OF PLATES (CAPTIONED PHOTOS) .................................................................... XI ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .......................................................................... XIII FOREWORD ...................................................................................................................... XV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................................ XVIII EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ XX CHAPTER ONE: .................................................................................................................... 1 COUNTY GENERAL INFORMATION ............................................................................... 1