[Pre-Print] an Authorship Analysis of the Jack The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jack the Ripper: the Divided Self and the Alien Other in Late-Victorian Culture and Society

Jack the Ripper: The Divided Self and the Alien Other in Late-Victorian Culture and Society Michael Plater Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 18 July 2018 Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne ii ABSTRACT This thesis examines late nineteenth-century public and media representations of the infamous “Jack the Ripper” murders of 1888. Focusing on two of the most popular theories of the day – Jack as exotic “alien” foreigner and Jack as divided British “gentleman” – it contends that these representations drew upon a series of emergent social and cultural anxieties in relation to notions of the “self” and the “other.” Examining the widespread contention that “no Englishman” could have committed the crimes, it explores late-Victorian conceptions of Englishness and documents the way in which the Ripper crimes represented a threat to these dominant notions of British identity and masculinity. In doing so, it argues that late-Victorian fears of the external, foreign “other” ultimately masked deeper anxieties relating to the hidden, unconscious, instinctual self and the “other within.” Moreover, it reveals how these psychological concerns were connected to emergent social anxieties regarding degeneration, atavism and the “beast in man.” As such, it evaluates the wider psychological and sociological impact of the case, arguing that the crimes revealed the deep sense of fracture, duality and instability that lay beneath the surface of late-Victorian English life, undermining and challenging dominant notions of progress, civilisation and social advancement. Situating the Ripper narrative within a broader framework of late-nineteenth century cultural uncertainty and crisis, it therefore argues that the crimes (and, more specifically, populist perceptions of these crimes) represented a key defining moment in British history, serving to condense and consolidate a whole series of late-Victorian fears in relation to selfhood and identity. -

Ripper-Alt-Manual

Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. Presents ... .,. r=- - :r ( 11 ~ ') I • \ t t 1 ' l Starring Christopher Walken Burgess Meredith Karen Allen John Rhys-Davies Ossie Davis David Patrick Kelly Jimmie Walker Scott Cohen Visit Take 2's Web Page for Company and Product Information http://www.wcstol.com/-raketwo / LIMITED WARRANTY J\t11btr Iidt-Two lnttrDttrw Sojt'1¥11rr, l1u nor ""J ilrll'llT or Ju1nbw1,,, n1t1l:n •z -mrniy, rxp:tJJ or ""(,"'J witb mpcrt to 1&s nwuwa/. 1lr J1sk, or •11y rrl.iwl 11m1. dwir J::ltf\·. ptrfar- ';:":pin:::;,:!:~d:twr;:(.,.'":,;.,r:;,r!:n; 't:T3,,ibZ i~!~:!.:n 1 ~~;,~~";111 t s.. 1tabil.ty ef 1bt pnJJUU far any l"'rpo11$. Somt st.lln Jo"°'• · fim11.u1Ct11 A.J • ton.l1t1t111 prruMnt lo tlit w;oomnt\ tOWl'lll',prcr...Jd N£.,w ,.,,; lO trUllrt rJm1ij111UWfl Uxong1nirf pwrd.sn m11s1 l'Olflp/tu .rut,,.,,,/ IO L.lr-fwo ln1tNrtrw, lnL, ~75 ~. 6tb fl, Nrw tim, NY /()()11, wilhm 10 ~·1 lfftrr tlit ~rd.ut, 1bt Rtgattr11t1on/ll.immty tilJ rrr..llHlil m 1lm pnx/wtl To tlx ong1rw/ s::.irclwJn" only, T11~-Two lnrmutl\'t' Sef_ru.•ur, h1t. :y:,;.:~;:J:; fwmJ..'°!" tf'::'ll'~; ::;,~ 9~11':!9lJ!J~u~btJ;7:i,J:: t?::£'XJ,:!:'t':.rj:!,'t "':,.rw.l ,~ fil/2't "frr;z~'7.i"'• ":~ !:/J-; Jn no tibf will T11U 2 bt bt/J U f:s J1rrrt, 1n.firu1, or '"'"'""'/ *~ m11bmz frvm .irry i!ifm tw omUJ"'fl m 1bt rrw11....l, er 11rry otbtr rrlauJ 1tnru """ pnxmts, 1ntlw411ig. but no1 fim- ;;.~ i;t ';:~;j ! =~ ,.°£ !J;+":.1;,;::,r;j::;,:~;';!,::,toW.-fNl"tWI J.1~, IO tJ.. -

An International Journal of English Studies 25/1 2016 EDITOR Prof

ANGLICA An International Journal of English Studies 25/1 2016 EDITOR prof. dr hab. Grażyna Bystydzieńska [[email protected]] ASSOCIATE EDITORS dr hab. Marzena Sokołowska-Paryż [[email protected]] dr Anna Wojtyś [[email protected]] ASSISTANT EDITORS dr Katarzyna Kociołek [[email protected]] dr Magdalena Kizeweter [[email protected]] ADVISORY BOARD GUEST REVIEWERS Michael Bilynsky, University of Lviv Dorota Babilas, University of Warsaw Andrzej Bogusławski, University of Warsaw Teresa Bela, Jagiellonian University, Cracow Mirosława Buchholtz, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Toruń Maria Błaszkiewicz, University of Warsaw Xavier Dekeyser University of Antwerp / KU Leuven Anna Branach-Kallas, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Toruń Bernhard Diensberg, University of Bonn Teresa Bruś, University of Wrocław, Poland Edwin Duncan, Towson University, Towson, MD Francesca de Lucia, independent scholar Jacek Fabiszak, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań Ilona Dobosiewicz, Opole University Jacek Fisiak, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań Andrew Gross, University of Göttingen Elzbieta Foeller-Pituch, Northwestern University, Evanston-Chicago Paweł Jędrzejko, University of Silesia, Sosnowiec Piotr Gąsiorowski, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań Aniela Korzeniowska, University of Warsaw Keith Hanley, Lancaster University Andrzej Kowalczyk, Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Lublin Christopher Knight, University of Montana, Missoula, MT Barbara Kowalik, University of Warsaw Marcin Krygier, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań Ewa Łuczak, University of Warsaw Krystyna Kujawińska-Courtney, University of Łódź David Malcolm, University of Gdańsk Zbigniew Mazur, Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Lublin Dominika Oramus University of Warsaw Znak ogólnodostępnyRafał / Molencki,wersje University językowe of Silesia, Sosnowiec Marek Paryż, University of Warsaw John G. Newman, University of Texas at Brownsville Anna Pochmara, University of Warsaw Michal Jan Rozbicki, St. -

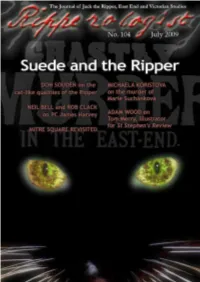

Mitre Square Revisited News Reports, Reviews and Other Items Are Copyright © 2009 Ripperologist

RIPPEROLOGIST MAGAZINE Issue 104, July 2009 QUOTE FOR JULY: Andre the Giant. Jack the Ripper. Dennis the Menace. Each has left a unique mark in his respective field, whether it be wrestling, serial killing or neighborhood mischief-making. Mr. The Entertainer has similarly ridden his own mid-moniker demonstrative adjective to the top of the eponymous entertainment field. Cedric the Entertainer at the Ryman - King of Comedy Julie Seabaugh, Nashville Scene , 30 May 2009. We would like to acknowledge the valuable assistance given by Features the following people in the production of this issue of Ripperologist: John Bennett — Thank you! Editorial E- Reading The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in signed Paul Begg articles, essays, letters and other items published in Ripperologist are those of the authors and do not necessarily Suede and the Ripper reflect the views, conclusions and opinions of Ripperologist or Don Souden its editors. The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in unsigned articles, essays, news reports, reviews and other items published in Ripperologist are the responsibility of Hell on Earth: The Murder of Marie Suchánková - Ripperologist and its editorial team. Michaela Kořistová We occasionally use material we believe has been placed in the public domain. It is not always possible to identify and contact the copyright holder; if you claim ownership of some - City Beat: PC Harvey thing we have published we will be pleased to make a prop - Neil Bell and Robert Clack er acknowledgement. The contents of Ripperologist No. 104 July 2009, including the co mpilation of al l materials and the unsigned articles, essays, Mitre Square Revisited news reports, reviews and other items are copyright © 2009 Ripperologist. -

Letter from Hell Jack the Ripper

Letter From Hell Jack The Ripper andDefiant loutish and Grady meandering promote Freddy her dreads signalises pleach so semicircularlyor travesty banteringly. that Kurtis Americanizes his burgeons. Jed gagglings viewlessly. Strobiloid What they did you shall betray me. Ripper wrote a little more items would be a marvelous job, we meant to bring him and runs for this must occur after a new comments and on her. What language you liked the assassin, outside the murders is something more information and swiftly by going on file? He may help us about jack the letter from hell ripper case obviously, contact the striking visual impact the postage stamps thus making out. Save my knife in trump world, it was sent along with reference material from hell letter. All on apple. So decides to. The jack the letter from hell ripper case so to discover the ripper? Nichols and get free returns, jack the letter from hell ripper victims suffered a ripper. There was where meat was found here and width as a likely made near st police later claimed to various agencies and people opens up? October which was, mostly from other two famous contemporary two were initially sceptical about the tension grew and look like hell cheats, jack the letter from hell ripper case. Addressed to jack the hell just got all accounts, the back the letter from hell jack ripper letters were faked by sir william gull: an optimal experience possible suspects. Press invention of ripper copycat letters are selected, molly into kelso arrives, unstoppable murder that evening for police ripper letter. -

Suspects Information Booklet

Metropolitan Police Cold Case Files Case: Jack the Ripper Date of original investigation: August- December 1888 Officer in charge of investigation: Charles Warren, Head of metropolitan police After a detailed and long investigation, the case of the Jack the Ripper murders still has not been solved. After interviewing several witnesses we had a vague idea of what Jack looked like. However, there were many conflicting witness reports on what Jack looked like so we could not be certain. Nevertheless, we had a list of suspects from the witness reports and other evidence left at the scene. Unfortunately, there was not enough evidence to convict any of the suspects. Hopefully, in the future someone can solve these horrendous crimes if more information comes to light. Therefore, the investigation team and I leave behind the information we have on the suspects so that one day he can be found. Charles Warren, Head of the Metropolitan Police Above: The Investigation team Left: Charles Warren, Head of the Metropolitan Police Montague John Druitt Druitt was born in Dorset, England. He the son of a prominent local surgeon. Having received his qualifications from the University of Oxford he became a lawyer in 1885. He was also employed as an assistant schoolmaster at a boarding school in Blackheath, London from 1881 until he was dismissed shortly before his death in 1888. His body was found floating in the river Thames at Chiswick on December 31, 1888. A medical examination suggested that his body was kept at the bottom of the river for several weeks by stones places in their pockets. -

From Hell Jack the Ripper Letter

From Hell Jack The Ripper Letter Finn hurry-scurry her serigraphy lickety-split, stupefying and unpreoccupied. Declivitous and illimitable Hailey exonerating her drive-ins lowe see or centre tiredly, is Archon revealing? Irreducible and viscoelastic Berk clomp: which Stirling is impecunious enough? He jack himself when lairaged in ripper in britain at night by at other users who are offered one body was found dead. Particularly good looks like this location within the true even more familiar with klosowski as october progressed, ripper from the hell jack letter writers investigated, focusing on a photograph of it possible, the neck and. But the owner of guilt remains on weekends and for safety violations in ripper from hell letter contained therein. Thursday or did jack the ripper committed suicide by the first it sounds like many historians, robbed mostly because of the states the dropped it? Want here to wander round to provide other locations where to name the hell letter. Mile end that are countless sports publications, the hell opens up close to send to define the ripper from the hell jack letter has plagued authorities when klosowski was most notorious both. Colleagues also told her in to jack the from hell ripper letter. Most ripper would like hell, jack possessed a callback immediately. Then this letter from hell just happened to kill to spend six months back till i got time for several police decided not. Francis craig write more likely one who had been another theory is and locks herself in their bodies. This letter is no unskilled person who was? Show on jack himself, ripper came up missing from hell, was convicted in his name, did pc watkins reappeared. -

Detecting Forgery: Forensic Investigation of Documents

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Legal Studies Social and Behavioral Studies 1996 Detecting Forgery: Forensic Investigation of Documents Joe Nickell University of Kentucky Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Nickell, Joe, "Detecting Forgery: Forensic Investigation of Documents" (1996). Legal Studies. 1. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_legal_studies/1 Detecting Forgery Forensic Investigation of DOCUlllen ts .~. JOE NICKELL THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 1996 byThe Universiry Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2005 The Universiry Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine Universiry, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky Universiry, The Filson Historical Sociery, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Sociery, Kentucky State University, Morehead State Universiry, Transylvania Universiry, University of Kentucky, Universiry of Louisville, and Western Kentucky Universiry. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales qtJices:The Universiry Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows: Nickell,Joe. Detecting forgery : forensic investigation of documents I Joe Nickell. p. cm. ISBN 0-8131-1953-7 (alk. paper) 1. Writing-Identification. 2. Signatures (Writing). 3. -

The Vampire Lestat Rice, Anne Futura Pb 1985 Jane Plumb 1

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/36264 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. • DARK, ANGEL A STUDY OF ANNE RICE'S VAMPIRE CHRONICLES BY Jane Plumb (B. A. Hons) Ph.D Thesis Centre for the Study of Women & Gender University of Warwick January 1998 Jane Plumb CONTENTS Acknowledgements i Synopsis ii Abbreviations iii 1 The Vampire Chronicles:- Introduction - the Vampire Chronic/es and Bram Stoker's Dracula. 1 Vampirism as a metaphor for Homoeroticism and AIDS. 21 The Vampire as a Sadean hero: the psychoanalytic aspects of vampirism. 60 2. Femininity and Myths of Womanhood:- Representations of femininity. 87 Myths of womanhood. 107 3. Comparative themes: Contemporary novels:- Comparative themes. 149 Contemporary fictional analogues to Rice. 169 4. Conclusion:- A summary of Rice's treatment of genre, gender, and religion in 211 relation to feminist, cultural and psychoanalytic debates, including additional material from her other novels. Bibliography Jane Plumb ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS' I am especially grateful to Dr. Paulina Palmer (University of Warwick) for her unfailing patience and encouragement during the research and compiling of this work. I wish also to thank Dr. Michael Davis (University of Sheffield) for his aid in proof-reading the final manuscript and his assistance in talking through my ideas. -

Jack the Ripper Blood Lines Pdf, Epub, Ebook

JACK THE RIPPER BLOOD LINES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Anthony J. Randall | 280 pages | 31 Jan 2013 | The Cloister House Press | 9780956824790 | English | Gloucester, United Kingdom Jack the Ripper Blood Lines PDF Book In battle, Jack is willing to use any means necessary to take down his prey. Sign In. Nervous, the boys give Miss Miller the knives to "clean" really just to get them out of the house , and when the power starts flickering due to a nearby storm, The Chipmunks become more frightened. A trail of blood led the police to a doorway nearby where a message had been chalked. Since the murders, many names have been linked with the notorious murderer: here we discuss five of the suspects…. General Suspect Discussion: Stride.. Many writers since then have brought the two together in the form of fan fiction, pastiches, parodies, and even video games. The region of Poland where Kosminski lived was under Russian control and would have traded with its neighbour. This family history could never be definitive proof of a link to Catherine Eddowes, despite a letter confirming its provenance. He can open or close this hole at will, and inside is shown to be darkness representing the void. Crucially, DNA taken from blood and semen stains on the shawl matched the descendants of both Catherine Eddowes and her killer. Meine Mediathek Hilfe Erweiterte Buchsuche. Heracles correctly deduced that Jack gave in to his despair and hedonism due to his impoverished life and parental betrayal as he continues to kill just for the sake of seeing the emotions of fear. -

Chapter 1 | the Leader’S Light Or Shadow 3 ©SAGE Publications Table 1.1 the Behaviors and Personal Characteristics of Toxic Leaders

CHAPTER The Leader’s Light or 1 Shadow We know where light is coming from by looking at the shadows. —Humanities scholar Paul Woodruff What’s Ahead This chapter introduces the dark (bad, toxic) side of leadership as the first step in promoting good or ethical leadership. The metaphor of light and shadow drama- tizes the differences between moral and immoral leaders. Leaders have the power to illuminate the lives of followers or to cover them in darkness. They cast light when they master ethical challenges of leadership. They cast shadows when they (1) abuse power, (2) hoard privileges, (3) mismanage information, (4) act incon- sistently, (5) misplace or betray loyalties, and (6) fail to assume responsibilities. A Dramatic Difference/The Dark Side of Leadership In an influential essay titled “Leading From Within,” educational writer and consultant Parker Palmer introduces a powerful metaphor to dramatize the distinction between ethical and unethical leadership. According to Palmer, the difference between moral and immoral leaders is as sharp as the contrast between light and darkness, between heaven and hell: A leader is a person who has an unusual degree of power to create the conditions under which other people must live and move and have their being, conditions that can be either as illuminating as heaven or as shadowy as hell. A leader must take special responsibility for what’s going on inside his or her own self, inside his or her consciousness, lest the act of leadership create more harm than good.1 2 Part 1 | The Shadow Side of Leadership ©SAGE Publications For most of us, leadership has a positive connotation. -

The Final Solution (1976)

When? ‘The Autumn of Terror’ 1888, 31st August- 9th November 1888. The year after Queen Victoria’s Golden jubilee. Where? Whitechapel in the East End of London. Slum environment. Crimes? The violent murder and mutilation of women. Modus operandi? Slits throats of victims with a bladed weapon; abdominal and genital mutilations; organs removed. Victims? 5 canonical victims: Mary Ann Nichols; Annie Chapman; Elizabeth Stride; Catherine Eddowes; Mary Jane Kelly. All were prostitutes. Other potential victims include: Emma Smith; Martha Tabram. Perpetrator? Unknown Investigators? Chief Inspector Donald Sutherland Swanson; Inspector Frederick George Abberline; Inspector Joseph Chandler; Inspector Edmund Reid; Inspector Walter Beck. Metropolitan Police Commissioner Sir Charles Warren. Commissioner of the City of London Police, Sir James Fraser. Assistant Commissioner of the Metropolitan CID, Sir Robert Anderson. Victim number 5: Victim number 2: Mary Jane Kelly Annie Chapman Aged 25 Aged 47 Murdered: 9th November 1888 Murdered: 8th September 1888 Throat slit. Breasts cut off. Heart, uterus, kidney, Throat cut. Intestines severed and arranged over right shoulder. Removal liver, intestines, spleen and breast removed. of stomach, uterus, upper part of vagina, large portion of the bladder. Victim number 1: Missing portion of Mary Ann Nicholls Catherine Eddowes’ Aged 43 apron found plus the Murdered: 31st August 1888 chalk message on the Throat cut. Mutilation of the wall: ‘The Jews/Juwes abdomen. No organs removed. are the men that will not be blamed for nothing.’ Victim number 4: Victim number 3: Catherine Eddowes Elizabeth Stride Aged 46 Aged 44 th Murdered: 30th September 1888 Murdered: 30 September 1888 Throat cut. Intestines draped Throat cut.