Gunther Schuller: Journey Into Jazz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Manatee PIANO MUSIC of the Manatee BERNARD

The Manatee PIANO MUSIC OF The Manatee BERNARD HOFFER TROY1765 PIANO MUSIC OF Seven Preludes for Piano (1975) 15 The Manatee [2:36] 16 Stridin’ Thru The Olde Towne 1 Prelude [2:40] 2 Cello [2:47] During Prohibition In Search Of A Drink [2:42] 3 All Over The Piano [1:21] Randall Hodgkinson, piano 4 Ships Passing [4:12] (2014) BERNARD HOFFER 5 Prelude [1:24] Events & Excursions for Two Pianos 6 Calypso [3:52] 17 Big Bang Theory [3:15] 7 Franz Liszt Plays Ragtime [3:28] 18 Running [3:19] Randall Hodgkinson, piano 19 Wexford Noon [2:29] 20 Reverberations [3:12] Nine New Preludes for Piano (2016) 21 On The I-93 [2:23] Randall Hodgkinson & Leslie Amper, pianos 8 Undulating Phantoms [1:08] BERNARD HOFFER 9 A Walk In The Park [2:39] 10 Speed Chess [2:17] 22 Naked (2010) [5:05] Randall Hodgkinson, piano 11 Valse Sentimental [3:30] 12 Rabbits [1:06] Total Time = 60:03 13 Spirals [1:40] 14 Canon Inverso [1:44] PIANO MUSIC OF TROY1765 WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM TROY1765 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 ALBANY RECORDS U.K. BOX 137, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA8 0XD TEL: 01539 824008 © 2019 ALBANY RECORDS MADE IN THE USA DDD WARNING: COPYRIGHT SUBSISTS IN ALL RECORDINGS ISSUED UNDER THIS LABEL. The Manatee PIANO MUSIC OF The Manatee BERNARD HOFFER WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM TROY1765 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 ALBANY RECORDS U.K. -

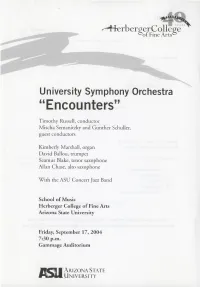

University Symphony Orchestra "Encounters"

FierbergerCollegeYEARS of Fine Arts University Symphony Orchestra "Encounters" Timothy Russell, conductor Mischa Semanitzky and Gunther Schuller, guest conductors Kimberly Marshall, organ David Ballou, trumpet Seamus Blake, tenor saxophone Allan Chase, alto saxophone With the ASU Concert Jazz Band School of Music Herberger College of Fine Arts Arizona State University Friday, September 17, 2004 7:30 p.m. Gammage Auditorium ARIZONA STATE M UNIVERSITY Program Overture to Nabucco Giuseppe Verdi (1813 — 1901) Timothy Russell, conductor Symphony No. 3 (Symphony — Poem) Aram ifyich Khachaturian (1903 — 1978) Allegro moderato, maestoso Allegro Andante sostenuto Maestoso — Tempo I (played without pause) Kimberly Marshall, organ Mischa Semanitzky, conductor Intermission Remarks by Dean J. Robert Wills Remarks by Gunther Schuller Encounters (2003) Gunther Schuller (b.1925) I. Tempo moderato II. Quasi Presto III. Adagio IV. Misterioso (played without pause) Gunther Schuller, conductor *Out of respect for the performers and those audience members around you, please turn all beepers, cell phones and watches to their silent mode. Thank you. Program Notes Symphony No. 3 – Aram Il'yich Khachaturian In November 1953, Aram Khachaturian acted on the encouraging signs of a cultural thaw following the death of Stalin six months earlier and wrote an article for the magazine Sovetskaya Muzika pleading for greater creative freedom. The way forward, he wrote, would have to be without the bureaucratic interference that had marred the creative efforts of previous years. How often in the past, he continues, 'have we listened to "monumental" works...that amounted to nothing but empty prattle by the composer, bolstered up by a contemporary theme announced in descriptive titles.' He was surely thinking of those countless odes to Stalin, Lenin and the Revolution, many of them subdivided into vividly worded sections; and in that respect Khachaturian had been no less guilty than most of his contemporaries. -

JAZZ WORTH READING: “THE BOSTON JAZZ CHRONICLES: FACES, PLACES and NIGHTLIFE 1937-1962″ Posted on February 20, 2014

From Michael Steinman’s blog JAZZ LIVES MAY YOUR HAPPINESS INCREASE. Jazz: where "lives" is both noun and verb JAZZ WORTH READING: “THE BOSTON JAZZ CHRONICLES: FACES, PLACES AND NIGHTLIFE 1937-1962″ Posted on February 20, 2014 Some of my readers will already know about Richard Vacca’s superb book, published in 2012 by Troy Street Publishing. I first encountered his work in Tom Hustad’s splendid book on Ruby Braff, BORN TO PLAY. Vacca’s book is even better than I could have expected. Much of the literature about jazz, although not all, retells known stories, often with an ideological slant or a “new” interpretation. Thus it’s often difficult to find a book that presents new information in a balanced way. BOSTON JAZZ CHRONICLES is a model of what can be done. And you don’t have to be particularly interested in Boston, or, for that matter, jazz, to admire its many virtues. Vacca writes that the book grew out of his early idea of a walking tour of Boston jazz spots, but as he found out that this landscape had been obliterated (as has happened in New York City), he decided to write a history of the scene, choosing starting and ending points that made the book manageable. The book has much to offer several different audiences: a jazz- lover who wants to know the Boston history / anecdotal biography / reportage / topography of those years; someone with local pride in the recent past of his home city; someone who wishes to trace the paths of his favorite — and some obscure — jazz heroes and heroines. -

Neglected Jazz Figures of the 1950S and Early 1960S New World NW 275

Introspection: Neglected Jazz Figures of the 1950s and early 1960s New World NW 275 In the contemporary world of platinum albums and music stations that have adopted limited programming (such as choosing from the Top Forty), even the most acclaimed jazz geniuses—the Armstrongs, Ellingtons, and Parkers—are neglected in terms of the amount of their music that gets heard. Acknowledgment by critics and historians works against neglect, of course, but is no guarantee that a musician will be heard either, just as a few records issued under someone’s name are not truly synonymous with attention. In this album we are concerned with musicians who have found it difficult—occasionally impossible—to record and publicly perform their own music. These six men, who by no means exhaust the legion of the neglected, are linked by the individuality and high quality of their conceptions, as well as by the tenaciousness of their struggle to maintain those conceptions in a world that at best has remained indifferent. Such perseverance in a hostile environment suggests the familiar melodramatic narrative of the suffering artist, and indeed these men have endured a disproportionate share of misfortunes and horrors. That four of the six are now dead indicates the severity of the struggle; the enduring strength of their music, however, is proof that none of these artists was ultimately defeated. Selecting the fifties and sixties as the focus for our investigation is hardly mandatory, for we might look back to earlier years and consider such players as Joe Smith (1902-1937), the supremely lyrical trumpeter who contributed so much to the music of Bessie Smith and Fletcher Henderson; or Dick Wilson (1911-1941), the promising tenor saxophonist featured with Andy Kirk’s Clouds of Joy; or Frankie Newton (1906-1954), whose unique muted-trumpet sound was overlooked during the swing era and whose leftist politics contributed to further neglect. -

Cobham Bellson.Sell.4

Pre-order date: Feb. 20, 2007 DVD NEW RELEASES Street date: Mar. 6, 2007 TIMELESS JAZZ LEGENDS from V.I.E.W. GIL EVANS AND HIS ORCHESTRA GIL EVANS View DVD #2301 – List Price $19.98 Gil Evans, one of the most notable arrangers and composers of the 20th century, with Randy and Michael Brecker, lent his conducting talents to jazz great Miles Davis (creating the landmark Billy Cobham, Lew Soloff, Birth of Cool) and played with the “Who’s Who” of jazz history. From collab- Herb Geller, Howard Johnson orating with Charlie Parker and Cannonball Adderley, to Art Blakey and Gerry and Mike Manieri Mulligan, Evans’ name is synonymous with jazz excellence. In this exclusive concert performance on DVD, Gil Evans leads an all-star band, which includes Randy and Michael Brecker, Billy Cobham, Lew Soloff and Mike Manieri. Song selections include Hotel Me, Stone Free, Here Comes de Honey Man, DVD BONUS FEATURES Friday the 13th and more. ➤ Gil Evans Biography ➤ Michael Brecker Biography “Yes, he definitely is the best.” –Miles Davis ➤ Randy Brecker Biography ➤ Billy Cobham Biography 57 minutes plus Multiple Bonus Features ➤ Gil Goldstein Biography VIEW DVD #2301 $19.98 VIEW VHS #1301 $19.98 ➤ Howard Johnson Biography ➤ Mike Manieri Biography ➤ Lew Soloff Biography ISBN 0-8030-2301-4 ➤ Instant Access to Songs and Solos “Yes, he definitely is the best.” –Miles Davis ➤ Digitally Re-mastered Audio and Video ➤ Dolby Stereo Audio 0 33909 23019 3 ➤ DVD Recommendations 40 YEARS OF MJQ View DVD #2350 – List Price $19.98 The distinguished Modern Jazz Quartet traces its origins to the irrepressibly YEARS OF flamboyant Dizzy Gillespie and his brazzy, shouting bebop big band. -

Windward Passenger

MAY 2018—ISSUE 193 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM DAVE BURRELL WINDWARD PASSENGER PHEEROAN NICKI DOM HASAAN akLAFF PARROTT SALVADOR IBN ALI Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East MAY 2018—ISSUE 193 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 NEw York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : PHEEROAN aklaff 6 by anders griffen [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : nicki parrott 7 by jim motavalli General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The Cover : dave burrell 8 by john sharpe Advertising: [email protected] Encore : dom salvador by laurel gross Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest We Forget : HASAAN IBN ALI 10 by eric wendell [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : space time by ken dryden US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or VOXNEwS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIVAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD ReviewS 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Mark Keresman, Marilyn Lester, Miscellany 43 Suzanne Lorge, Marc Medwin, Russ Musto, John Pietaro, Joel Roberts, John Sharpe, Elliott Simon, Event Calendar 44 Andrew Vélez, Scott Yanow Contributing Writers Kevin Canfield, Marco Cangiano, Pierre Crépon George Grella, Laurel Gross, Jim Motavalli, Greg Packham, Eric Wendell Contributing Photographers In jazz parlance, the “rhythm section” is shorthand for piano, bass and drums. -

Printcatalog Realdeal 3 DO

DISCAHOLIC auction #3 2021 OLD SCHOOL: NO JOKE! This is the 3rd list of Discaholic Auctions. Free Jazz, improvised music, jazz, experimental music, sound poetry and much more. CREATIVE MUSIC the way we need it. The way we want it! Thank you all for making the previous auctions great! The network of discaholics, collectors and related is getting extended and we are happy about that and hoping for it to be spreading even more. Let´s share, let´s make the connections, let´s collect, let´s trim our (vinyl)gardens! This specific auction is named: OLD SCHOOL: NO JOKE! Rare vinyls and more. Carefully chosen vinyls, put together by Discaholic and Ayler- completist Mats Gustafsson in collaboration with fellow Discaholic and Sun Ra- completist Björn Thorstensson. After over 33 years of trading rare records with each other, we will be offering some of the rarest and most unusual records available. For this auction we have invited electronic and conceptual-music-wizard – and Ornette Coleman-completist – Christof Kurzmann to contribute with some great objects! Our auction-lists are inspired by the great auctioneer and jazz enthusiast Roberto Castelli and his amazing auction catalogues “Jazz and Improvised Music Auction List” from waaaaay back! And most definitely inspired by our discaholic friends Johan at Tiliqua-records and Brad at Vinylvault. The Discaholic network is expanding – outer space is no limit. http://www.tiliqua-records.com/ https://vinylvault.online/ We have also invited some musicians, presenters and collectors to contribute with some records and printed materials. Among others we have Joe Mcphee who has contributed with unique posters and records directly from his archive. -

Ron Mcclure • Harris Eisenstadt • Sackville • Event Calendar

NEW YORK FebruaryVANGUARD 2010 | No. 94 Your FREE Monthly JAZZ Guide to the New ORCHESTRA York Jazz Scene newyork.allaboutjazz.com a band in the vanguard Ron McClure • Harris Eisenstadt • Sackville • Event Calendar NEW YORK We have settled quite nicely into that post-new-year, post-new-decade, post- winter-jazz-festival frenzy hibernation that comes so easily during a cold New York City winter. It’s easy to stay home, waiting for spring and baseball and New York@Night promising to go out once it gets warm. 4 But now is not the time for complacency. There are countless musicians in our fair city that need your support, especially when lethargy seems so appealing. To Interview: Ron McClure quote our Megaphone this month, written by pianist Steve Colson, music is meant 6 by Donald Elfman to help people “reclaim their intellectual and emotional lives.” And that is not hard to do in a city like New York, which even in the dead of winter, gives jazz Artist Feature: Harris Eisenstadt lovers so many choices. Where else can you stroll into the Village Vanguard 7 by Clifford Allen (Happy 75th Anniversary!) every Monday and hear a band with as much history as the Vanguard Jazz Orchestra (On the Cover). Or see as well-traveled a bassist as On The Cover: Vanguard Jazz Orchestra Ron McClure (Interview) take part in the reunion of the legendary Lookout Farm 9 by George Kanzler quartet at Birdland? How about supporting those young, vibrant artists like Encore: Lest We Forget: drummer Harris Eisenstadt (Artist Feature) whose bands and music keep jazz relevant and exciting? 10 Svend Asmussen Joe Maneri In addition to the above, this month includes a Lest We Forget on the late by Ken Dryden by Clifford Allen saxophonist Joe Maneri, honored this month with a tribute concert at the Irondale Center in Brooklyn. -

Open Dissertation Holt Format Final

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School School of Visual Arts USER EXPERIENCE WITH ARCHIVES AND FEMINIST TEACHING CONVERSATIONS WITH THE JUDY CHICAGO ART EDUCATION COLLECTION A Dissertation in Art Education by Ann E. Holt © 2015 Ann E. Holt Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2015 The dissertation of Ann E. Holt was reviewed and approved* by the following: Karen Keifer-Boyd Professor of Art Education and Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies Dissertation Co-Advisor Dissertation Co-Chair Patricia Amburgy Associate Professor Emerita of Art Education Dissertation Co-Advisor Dissertation Co-Chair Wanda B. Knight Associate Professor of Art Education and Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies Grace Hampton Professor Emerita of Art, Art Education, and Integrative Arts Michelle Rodino-Colocino Associate Professor of Media Studies and Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies Jacqueline Esposito Professor, University Archivist and Head of Records Management Services Special Member Graeme Sullivan Department Head Professor of Art Education, Director of the School of Visual Arts *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT This is a case study of three university professors’ archival experience with the Judy Chicago Art Education Collection through their participation in feminist Teaching Conversations. The Judy Chicago Art Education Collection is a living archive of materials on feminist art pedagogy. Teaching Conversations is a feminist orientation to archives that is ongoing and involves participatory engagement and transdisciplinary dialogue to support teaching and using the collection for creating living curricula. The professors are situated in different disciplines and, differ in their teaching and research foci. -

Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: the Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa

STYLISTIC EVOLUTION OF JAZZ DRUMMER ED BLACKWELL: THE CULTURAL INTERSECTION OF NEW ORLEANS AND WEST AFRICA David J. Schmalenberger Research Project submitted to the College of Creative Arts at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Percussion/World Music Philip Faini, Chair Russell Dean, Ph.D. David Taddie, Ph.D. Christopher Wilkinson, Ph.D. Paschal Younge, Ed.D. Division of Music Morgantown, West Virginia 2000 Keywords: Jazz, Drumset, Blackwell, New Orleans Copyright 2000 David J. Schmalenberger ABSTRACT Stylistic Evolution of Jazz Drummer Ed Blackwell: The Cultural Intersection of New Orleans and West Africa David J. Schmalenberger The two primary functions of a jazz drummer are to maintain a consistent pulse and to support the soloists within the musical group. Throughout the twentieth century, jazz drummers have found creative ways to fulfill or challenge these roles. In the case of Bebop, for example, pioneers Kenny Clarke and Max Roach forged a new drumming style in the 1940’s that was markedly more independent technically, as well as more lyrical in both time-keeping and soloing. The stylistic innovations of Clarke and Roach also helped foster a new attitude: the acceptance of drummers as thoughtful, sensitive musical artists. These developments paved the way for the next generation of jazz drummers, one that would further challenge conventional musical roles in the post-Hard Bop era. One of Max Roach’s most faithful disciples was the New Orleans-born drummer Edward Joseph “Boogie” Blackwell (1929-1992). Ed Blackwell’s playing style at the beginning of his career in the late 1940’s was predominantly influenced by Bebop and the drumming vocabulary of Max Roach. -

How to Play in a Band with 2 Chordal Instruments

FEBRUARY 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

Jazz Piano Handbook

LISTENING Listening to master musicians is an essential part of the learning process. While there is no substitute for experiencing live music, recordings are the great textbooks for students of jazz. So, I encourage you to listen to recordings between classes, in the car, or when doing chores. In addition, focused listening, without distraction, can help you understand jazz music at a deeper level and will contribute to your overall development. Who to Listen To There are hundreds of great jazz recordings, and it can be difficult for students to know where to start. Today, you can listen to a lot of great music through services such as youtube, Pandora, and Spotify. Many libraries also have wonderful jazz collections. In addition, concerts and television appearances from classic jazz groups are now available on DVD. By their nature, lists of essential jazz recordings are somewhat arbitrary and generally incomplete; the list below is no exception. However, as a reference, I have assembled this list of some of the great jazz rhythm sections and important horn players. They are listed below in rough chronological order. Important Rhythm Sections • Count Basie/Walter Page/Jo Jones/Freddie Green (guitar) – This unit is the model for modern rhythm sections. They swing whether they are playing loud or soft. Some more modern Basie rhythm sections can be heard on Atomic Basie and Frankly Speaking. • Bud Powell/Charlie Mingus/Max Roach – This is the quintessential bebop rhythm section. A great recording featuring Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie is The Quintet: Jazz at Massey Hall. • Modern Jazz Quartet – John Lewis/Percy Heath/Connie Kay/Milt Jackson (vibes) – This quartet performed together for decades.