Wiretapping Smart Phones with Rotary–Dial Phones'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Perspectives of Development of Antique Analog Telephone Systems Vinayak L

Review Historical Perspectives of Development of Antique Analog Telephone Systems Vinayak L. Patil Trinity College of Engineering and Research, University of Pune, Pune, India Abstract—Long distance voice communication has been al- ways of great interest to human beings. His untiring efforts and intuition from many years together was responsible for making it to happen to a such advanced stage today. This pa- per describes the development time line of antique telephone systems, which starts from the year 1854 and begins with the very early effort of Antonio Meucci and Alexander Graham magnet core Bell and ends up to the telephone systems just before digiti- Wire 1Coil with permanent Wire 2 zation of entire telecommunication systems. The progress of development of entire antique telephone systems is highlighted in this paper. The coverage is limited to only analog voice communication in a narrow band related to human voice. Diaphragm Keywords—antique telephones, common battery systems, cross- bar switches, PSTN, voice band communication, voice commu- nication, strowger switches. Fig. 1. The details of Meucci’s telephone. 1. Initial Claims and Inventions Since centuries, telecommunications have been of great cally. Due to this idea, many of the scientific community interest to the human beings. One of the dignified per- consider him as one of the inventors of telephone [10]. sonality in the field of telecommunication was Antonio Boursuel used term “make and break” telephone in his Meucci [1]–[7] (born in 1808) who worked relentlessly for work. In 1850, Philip Reis [11]–[13] began work on tele- communication to distant person throughout his life and in- phone. -

The Panel Dial Telephone Switching System Douglas A. Kerr Issue 6 June 15, 2018

The panel dial telephone switching system Douglas A. Kerr Issue 6 June 15, 2018 ABSTRACT In the 1910s, AT&T, the parent of the Bell Telephone System, anxious to reduce the stupendous labor costs of manual telephone switching (especially in large metropolitan areas), and realizing that the most prominent available switching system (the Strowger system) had serious limitations of its use in such areas, undertook the development from the ground up of a switching system based on many entirely new concepts. This system, the panel dial switching system, came to be the mainstay of the Bell System’s program of mechanizing telephone service in many of the largest cities in the U.S. In this article, we will learn of the evolution of this system, of the unique mechanisms around which it revolves, and of the implications of its basic operational principle, known as common control. Considerable detail in system operation is given, although not usually at the circuit level, except where necessary to illustrate an important concept. 1 HISTORICAL CONTEXT 1.1 The telephone industry in 1910 By 1910, the telephone industry in the United States was well on the way to its “classical” structure, which existed until about 1984. The Bell Telephone System, owned by American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T), was becoming the major force in the industry, and provided local telephone service in most of the nation’s largest cities (often after acquiring existing locally-owned telephone companies, sometime several competing ones in the same city, whose operations had to be harmonized and consolidated). In about 1907, AT&T adopted the slogan, “One Policy, One System, Universal Service”. -

Sangamo Data

TCI Library www.telephonecollectors.info INSTALLATION AND OPERATION MANUAL RIXON-SANGAMO TlOlCSC SERIES DATA SET SYSTEM Rixon, Inc. A Subsidiary of Sangamo 2120 Industrial Parkway Silver Spring, Maryland 20904 BULLETIN 5367 ISSUE 1 Part No. 693729 November, 1 972 TCI Library www.telephonecollectors.info '-- -- TCI Library www.telephonecollectors.info ISS. 1, BULLETIN 5367 INTRODUCTION This manual contains the information series. A list of equipment necessary to install and operate the various specifications is also included. T101 CSC Data Set Systems, manufactured by Sangamo Electric Company, in conjunction with 2-0 INSTALLATION AND the teletypewriter and data access arrangement CONNECTION - Supplies detailed ( DAA). Instructions are also provided for procedures for unpacking, installing, teletypewriter modification. For maintenance and connecting the different data set and troubleshooting assistance, contact the systems. Also provides teletypewriter Communication Systems Data Service Center, modification procedures. Sangamo Electric Company, Springfield, Illinois. The information provided by this manual is 3-0 OPERATION - Describes the grouped into four sections. A brief description complete procedures for operating the of each section is provided below: different data set systems with the various teletypewriters. 1-0 GENERAL DESCRIPTION - 4-0 DRAWINGS AND DIAGRAMS Provides general information about Furnishes the connection diagrams for data set and auxiliary equipment. each data set system when connected Describes the various applications -

Tone Commander RT-3600 Tone-Rotary Dial Intercom

TONE COMMANDER SYSTEMS, INC. 4320 l'Oth Ave. N.E., Redmond, WA 980'2, U.s.A Telephone: (206) 883-3600, Telex: 32-8055 RT-3600 KEY TELEPHONE UNIT TONE AND ROTARY DIAL INTERCOM TECHNICAL INSTRUCTION Document #13-100444 REV. E April 1981 CONTENTS 1. GENERAL INFORMAnON 2. PRODUCT IDENTIFICAnON 3. INSTALLAnON 4. OPERATING INSTRUCnONS ,. SERVICE INFORMAnON 1. GENERAL INFORMATION , Description of Product Fig. 1 - RT-3600 Key Telephone Unit 1.01 The RT-3600 is a thirty-six code selective signaling unit. It provides • This unit must be installed by telephone common talk path intercom service for most company personnel or agents authorized Key Telephone Systems that use rotary, tone under Part 68 of FCC Rules and or mixed dialing. Regulations. Manual Changes • This unit must not be installed on coin operated or party line telephones. 1.02 This document is reissued to change the warranty date from 18 months to 36 • If this unit malfunctions, the telephone months. company may· disconnect service temporarily. If disconnection is Federal Communications Commission necessary, the telephone company must (FCC) Regulations attempt to notify the user in advance, 1.03 To comply with FCC regulations, the if possible. If not, they must notify the following requirements must be met: user as soon as they are able. • Upon installation, the FCC registration • Repair work on this unit must be done number of this unit must be reported to by TeS. the telephone company. Page 1 of 6 DOCUMENT 1113-100444 REV. E RT-3600 KEY TELEPHONE UNIT 2. PRODUCT IDENTIFICATION _ 2.05 Tone Decoder Features -- Application • Digital decoding process offers superior tone decoding. -

Searchable PDF Index

TELEPHONE COLLECTORS INTERNATIONAL Telephone Collectors International is an organization of telephone collectors, hobbyists and historians who are helping to preserve the history of the telecommunications industry through the collection of telephones and telephone related material. Our collections represent all aspects of the industry; from the very first wooden prototypes that started the industry to the technological marvels that made the automatic telephone exchange possible. If any of this interests you, we invite you to join our organization. Look around and see what we have to offer. Thanks for stopping by! Telephone Collectors International website including become a member: http://www.telephonecollectors.org/ Questions or comments about TCI? Send e-mail to [email protected] ********************************************************************************* Books Recommended by the editors: Available now ... Old-Time Telephones! Design, History, and Restoration by Ralph O. Meyer ... 264pp Soft Cover 2nd Edition, Expanded and Revised ... A Schiffer Book with Price Guide for Collectors Available at Phoneco.com or Schiffer Publishing, Ltd., 4880 Lower Valley Rd, Atglen, PA 19310 e-mail: [email protected] ********************************************************************************** Coming Soon: TELEPHONE Dials and Pushbuttons Their History, Development and Usage by Stanley Swihart ... 2 volumes, 300 pp ea. Box 2818, Dublin, CA., 94568-0818. Phone 1 (925)-829-2728, e-mail [email protected] ********************************************************************************* -

DTMF Modem with Tone Generation and Detection Using Goertzel Algorithm with MATLAB

CH. Sreeja Reddy et al, International Journal of Computer Science and Mobile Computing, Vol.6 Issue.4, April- 2017, pg. 78-89 Available Online at www.ijcsmc.com International Journal of Computer Science and Mobile Computing A Monthly Journal of Computer Science and Information Technology ISSN 2320–088X IMPACT FACTOR: 6.017 IJCSMC, Vol. 6, Issue. 4, April 2017, pg.78 – 89 DTMF Modem with Tone Generation and Detection Using Goertzel Algorithm with MATLAB CH. Sreeja Reddy1, S.Durga Bhavani2, M.Bhavani Marati3, C.Divyani4, NAGARJUNA.T5 # CMR TECHNICAL CAMPUS, CMRGI EDUCATIONAL SOCIETY, MEDCHAL, TELANGANA -501 401 1 B.Tech Student (ECE), CMR Technical Campus, Medchal Dist-501 401, India 2B.Tech Student (ECE), CMR Technical Campus, Medchal Dist-501 401, India 3B.Tech Student (ECE), CMR Technical Campus, Medchal Dist-501 401, India 4B.Tech Student (ECE), CMR Technical Campus, Medchal Dist-501 401, India 5 Assistant Professor (M.Tech), CMR Technical Campus, Medchal Dist-501 401, India e-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract - Dual-tone multi-frequency (DTMF) signalling is a standard in telecommunication systems. This is a standard where keystrokes from the telephone keypad are translated into dual tone signals over the audio link. It has been gaining popularity for some years now because of its numerous advantages over the traditional telephone signalling scheme. In this project DTMF tone generation and the detection can be done with the help of MATLAB. The Goertzel algorithm implementation examines the energy of one of the two tones from an incoming signal at 8 DTMF frequencies to determine which DTMF frequency is present. -

Historical Timeline of Canadian Telecommunications Achievements

Historical Timeline of Canadian Telecommunications Achievements July 26, 1874 Alexander Graham Bell discloses idea for a telephone to his father in Brantford, Ontario. 1880 Bell Canada is incorporated. February 1, 1881 Bell Canada installs its first public telephone in Lancefield’s Stationery Store, in Hamilton, Ontario. The telephone is not equipped with a coin collector and customers pay the storekeeper. June 11, 1881 Bell Canada successfully places the world's first international submarine telephone cable between Windsor, Ontario and Detroit, Michigan (US). 1885 Alberta's first telephone call, between Fort Edmonton and the St. Albert mission. August 10, 1876 Alexander Graham Bell's Double Pole Membrane Transmitter and Iron Box Receiver are used to transmit and receive the world's first one-way long distance telephone call from Brantford to Paris, Ontario. 1887 The first long distance call, between Edmonton and Battleford, Saskatchewan. December 7, 1895 The Northern Electric & Manufacturing Co., now Nortel Networks, is organized, as a spin-off of the Bell Mechanical Department. April 13, 1900 A common battery service is introduced in Bell Canada’s territory in Ottawa, Ontario. Instead of turning a crank on the telephone to signal the operator, the customer merely picks up the receiver. The batteries are removed from the customers’ premises to the central office. They are still there today, maintaining telephone service even during a power failure. 1903 Bell Canada becomes subject to the Railway Act of 1903 and changes to rates for telephone service must now be approved by the Board of Railway Commissioners for Canada. 1904 The City of Edmonton purchased the Edmonton District Telephone Company. -

Historical Perspectives of Development of Antique Analog Telephone Systems Vinayak L

Review Historical Perspectives of Development of Antique Analog Telephone Systems Vinayak L. Patil Trinity College of Engineering and Research, University of Pune, Pune, India Abstract—Long distance voice communication has been al- ways of great interest to human beings. His untiring efforts and intuition from many years together was responsible for making it to happen to a such advanced stage today. This pa- per describes the development time line of antique telephone systems, which starts from the year 1854 and begins with the very early effort of Antonio Meucci and Alexander Graham magnet core Bell and ends up to the telephone systems just before digiti- Wire 1Coil with permanent Wire 2 zation of entire telecommunication systems. The progress of development of entire antique telephone systems is highlighted in this paper. The coverage is limited to only analog voice communication in a narrow band related to human voice. Diaphragm Keywords—antique telephones, common battery systems, cross- bar switches, PSTN, voice band communication, voice commu- nication, strowger switches. Fig. 1. The details of Meucci’s telephone. 1. Initial Claims and Inventions Since centuries, telecommunications have been of great cally. Due to this idea, many of the scientific community interest to the human beings. One of the dignified per- consider him as one of the inventors of telephone [10]. sonality in the field of telecommunication was Antonio Boursuel used term “make and break” telephone in his Meucci [1]–[7] (born in 1808) who worked relentlessly for work. In 1850, Philip Reis [11]–[13] began work on tele- communication to distant person throughout his life and in- phone. -

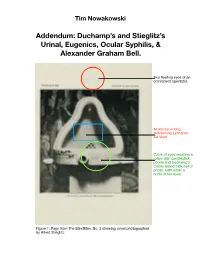

Addendum- Duchamp's and Stieglitz's Urinal, Eugenics, Ocular Syphilis

Tim Nowakowski Addendum: Duchamp’s and Stieglitz’s Urinal, Eugenics, Ocular Syphilis, & Alexander Graham Bell. Two floating eyes of an omniscient spectator. Mirrorical writing referencing Leonardo Da Vinci. Circle of eyes recalling a rotary dial candlestick phone and Duchamp’s Coney Island trick mirror photo, both entail a circle of ten eyes. Figure 1. Page from The BlindMan, No. 2 showing urinal photographed by Alfred Stieglitz. Figure 2. Derivative graphics from The Blind Man, No. 2, copyright by Tim Nowakowski, illustrating the circle of 10 ‘eyes’ bleeding through from the other side of the page, composing in effect a simulation of a candlestick rotary dial phone. Figure 3. Figure 4. Unknown photographer, 5-way portrait of Duchamp. Duchamp having a Spiritualist seance with himself(s), the foreground figure showing the back of his head anticipating the back turned head in Tonsure as well as the Apple-bowl Billiard style smoking pipe. This vaguely compares to the cluster of bachelors in the LG. Divining the presence of eugenics within Marcel Duchamp/Alfred Stieglitz’s Fountain, The BlindMan, No.2, and Rongwrong, reveals some problems in Duchampian scholarship. Traveling from England via a stay with Mable Dodge in Florence, writer/ poet/painter of lampshades Mina Loy, well represented in both Blind Man editions, wrote works which led critics of British literature to characterize her as the eugenics madonna or ‘race mother’. (See this author’s Marcel Duchamp: Eugenics, Race Suicide, dénatalité, State Selective Breeding, Mina Loy, R. Mutt, Roosevelt Mutt and Rongwrong Mutt). Duchamp’s ‘race suicide’ comment here and mandatory government-sponsored natalism suggested in the McBride article, mentioned previously, perplexingly yields no such discourse on race degeneracy among scholars of Duchamp. -

Jonathan Anguleov

Evolution of the Smartphone From tin cans and strings, to always on: The evolution of the business phone by Jonathan Anguelov, COO and co-founder, Aircall It’s not hard to understand how the phone became so integral to business transactions. However, the business phones of yesteryear are a far cry from the integrated cloud-based phone systems we see today. Nowadays, you can use highly intelligent software on your laptop or mobile to instantly message or speak to anyone you want, while pulling up their profile to glean useful information - a very handy tool, especially for sales and customer support teams. This was the mentality behind building Aircall - to empower companies of any size with an online phone system specifically tailored to the needs of modern businesses. Jonathan is the Co-founder & COO at Aircall, one of the fastest growing cloud phone systems. As a COO, Jonathan focuses on Aircall’s growth and is directly in charge of the EMEA offices. Jonathan began his career into the financial industry as a stockbroker and equity research analyst into different banks and investment funds, in Paris and in London. He is passionate about real estate, and has graduated from ESCP Europe with a Master degree. Alexander Graham Bell’s first phone call Communication on the go of communication on the go. Due to the in 1876 was a revolutionary breakthrough prohibitive cost of mobiles, they were used in the way we communicate with each It’s not hard to understand how the phone primarily by businessmen, who needed to other. Rather than send a letter, or arrange a became so integral to business transactions. -

Appendix 9 Glossary Access Line (Wats)

APPENDIX 9 GLOSSARY ACCESS LINE (WATS) - A telephone line connected to the customer's premises to either establish or receive calls to or from a particular WATS Service Area. AMA (AUTOMATIC MESSAGE ACCOUNTING) - GSA furnished reports providing a tabulation of FTS calls, indicating the date, area code, telephone number called, time of day, and duration. ANALOG - As opposed to digital. Signals which make use of electrical analogies (e.g., varying voltages, frequencies) to produce a signal of a continuous nature rather than a pulse nature. ANSWERBACK (DATA) - A signal or tone sent by the receiving business machine or data set to the sending station for identification or to indicate it is ready to receive transmission. AREA CODE - The three-digit code used when dialing long distance calls from one Number-Plan Area (NPA) to another. ASCII - American Standard Code for Information Interchange. This is the code established as an American standard by the American Standard Association. ASR - Automatic Send and Receive. BROADCAST - The dissemination of information to a number of stations simultaneously. BUSY HOUR - The peak 60-minute period during a business day when the largest volume of communications traffic is handled. CARD DIALER - Automatic dialer and regular telephone combined in one desk-top unit. Phone numbers coded on plastic cards are inserted in the dialer slot for fast, accurate dialing or touch-tone entry of fixed data into a data processing system. CATHODE RAY TUBE (CRT) - A television-like picture tube used in visual display terminals. CCSA - Common Control Switching Arrangements; designed for customers having extensive private line communications requirements. -

Dual Tone Multi Frequency Signaling

Contents 1 Introduction 2 2 History and Evolution 3 3 Technology 5 3.1 DTMF Keys 5 3.2 DTMF Frequencies 6 3.3 Special Tones 7 3.4 DTMF Transmission 8 3.5 DTMF Programming 9 4 Technical Standards 11 5 Applications 12 5.1 Applications in the Call Center Industry 13 6 VoIP and DTMF 14 7 Advantages of Using DTMF 15 8 Conclusion 16 9 References 17 1 © Specialty Answering Service. All rights reserved. 1 Introduction Dual Tone Multi Frequency, or DTMF as it is popularly known as, is the technical term for the sound frequencies produced when a telephonic key is pressed. DTMF, also known as touch tone, was primarily used for telephone signaling to and from the local exchange, though today it finds several applications in the field of telecommunications and call centers. A different frequency is assigned to each key in the telephone and there are two tones – one low frequency and another high frequency – that are played simultaneously when a key is pressed. This combination of two tones makes it nearly impossible to reproduce by the human voice. Each of the four rows of keys in a telephone is assigned a low frequency tone and each of the three columns is assigned a high frequency tone. A fourth column of keys labeled as A, B, C, and D is optional and is mostly used in military networks. 2 © Specialty Answering Service. All rights reserved. 2 History and Evolution Before DTMF was introduced, telephone networks were dependent on pulse dialing. In pulse dialing, pulses are generated by rapidly connecting and disconnecting the telephone connection.