University Micrdrilms International 300 N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

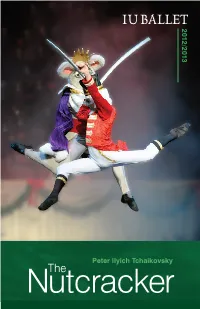

Nutcracker Three Hundred Sixty-Seventh Program of the 2012-13 Season ______Indiana University Ballet Theater Presents

2012/2013 Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky NutcrackerThe Three Hundred Sixty-Seventh Program of the 2012-13 Season _______________________ Indiana University Ballet Theater presents its 54th annual production of Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker Ballet in Two Acts Scenario by Michael Vernon, after Marius Petipa’s adaptation of the story, “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King” by E. T. A. Hoffmann Michael Vernon, Choreography Andrea Quinn, Conductor C. David Higgins, Set and Costume Designer Patrick Mero, Lighting Designer Gregory J. Geehern, Chorus Master The Nutcracker was first performed at the Maryinsky Theatre of St. Petersburg on December 18, 1892. _________________ Musical Arts Center Friday Evening, November Thirtieth, Eight O’Clock Saturday Afternoon, December First, Two O’Clock Saturday Evening, December First, Eight O’Clock Sunday Afternoon, December Second, Two O’Clock music.indiana.edu The Nutcracker Michael Vernon, Artistic Director Choreography by Michael Vernon Doricha Sales, Ballet Mistress Guoping Wang, Ballet Master Shawn Stevens, Ballet Mistress Phillip Broomhead, Guest Coach Doricha Sales, Children’s Ballet Mistress The children in The Nutcracker are from the Jacobs School of Music’s Pre-College Ballet Program. Act I Party Scene (In order of appearance) Urchins . Chloe Dekydtspotter and David Baumann Passersby . Emily Parker with Sophie Scheiber and Azro Akimoto (Nov. 30 & Dec. 1 eve.) Maura Bell with Eve Brooks and Simon Brooks (Dec. 1 mat. & Dec. 2) Maids. .Bethany Green and Liara Lovett (Nov. 30 & Dec. 1 eve.) Carly Hammond and Melissa Meng (Dec. 1 mat. & Dec. 2) Tradesperson . Shaina Rovenstine Herr Drosselmeyer . .Matthew Rusk (Nov. 30 & Dec. 1 eve.) Gregory Tyndall (Dec. 1 mat.) Iver Johnson (Dec. -

The Evolution of Musical Theatre Dance

Gordon 1 Jessica Gordon 29 March 2010 Honors Thesis Everything was Beautiful at the Ballet: The Evolution of Musical Theatre Dance During the mid-1860s, a ballet troupe from Paris was brought to the Academy of Music in lower Manhattan. Before the company’s first performance, however, the theatre in which they were to dance was destroyed in a fire. Nearby, producer William Wheatley was preparing to begin performances of The Black Crook, a melodrama with music by Charles M. Barras. Seeing an opportunity, Wheatley conceived the idea to combine his play and the displaced dance company, mixing drama and spectacle on one stage. On September 12, 1866, The Black Crook opened at Niblo’s Gardens and was an immediate sensation. Wheatley had unknowingly created a new American art form that would become a tradition for years to come. Since the first performance of The Black Crook, dance has played an important role in musical theatre. From the dream ballet in Oklahoma to the “Dance at the Gym” in West Side Story to modern shows such as Movin’ Out, dance has helped tell stories and engage audiences throughout musical theatre history. Dance has not always been as integrated in musicals as it tends to be today. I plan to examine the moments in history during which the role of dance on the Broadway stage changed and how those changes affected the manner in which dance is used on stage today. Additionally, I will discuss the important choreographers who have helped develop the musical theatre dance styles and traditions. As previously mentioned, theatrical dance in America began with the integration of European classical ballet and American melodrama. -

Twyla Tharp Th Anniversary Tour

Friday, October 16, 2015, 8pm Saturday, October 17, 2015, 8pm Sunday, October 18, 2015, 3pm Zellerbach Hall Twyla Tharp D?th Anniversary Tour r o d a n a f A n e v u R Daniel Baker, Ramona Kelley, Nicholas Coppula, and Eva Trapp in Preludes and Fugues Choreography by Twyla Tharp Costumes and Scenics by Santo Loquasto Lighting by James F. Ingalls The Company John Selya Rika Okamoto Matthew Dibble Ron Todorowski Daniel Baker Amy Ruggiero Ramona Kelley Nicholas Coppula Eva Trapp Savannah Lowery Reed Tankersley Kaitlyn Gilliland Eric Otto These performances are made possible, in part, by an Anonymous Patron Sponsor and by Patron Sponsors Lynn Feintech and Anthony Bernhardt, Rockridge Market Hall, and Gail and Daniel Rubinfeld. Cal Performances’ – season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. PROGRAM Twyla Tharp D?th Anniversary Tour “Simply put, Preludes and Fugues is the world as it ought to be, Yowzie as it is. The Fanfares celebrate both.”—Twyla Tharp, 2015 PROGRAM First Fanfare Choreography Twyla Tharp Music John Zorn Musical Performers The Practical Trumpet Society Costumes Santo Loquasto Lighting James F. Ingalls Dancers The Company Antiphonal Fanfare for the Great Hall by John Zorn. Used by arrangement with Hips Road. PAUSE Preludes and Fugues Dedicated to Richard Burke (Bay Area première) Choreography Twyla Tharp Music Johann Sebastian Bach Musical Performers David Korevaar and Angela Hewitt Costumes Santo Loquasto Lighting James F. Ingalls Dancers The Company The Well-Tempered Clavier : Volume 1 recorded by MSR Records; Volume 2 recorded by Hyperi on Records Ltd. INTERMISSION PLAYBILL PROGRAM Second Fanfare Choreography Twyla Tharp Music John Zorn Musical Performers American Brass Quintet Costumes Santo Loquasto Lighting James F. -

The Psychosocial Effects of Compensated Turnout on Dancers: a Critical Look at the Leading Cause of Non-Traumatic Dance Injuries

University of Tennessee at Chattanooga UTC Scholar Student Research, Creative Works, and Honors Theses Publications 5-2018 The psychosocial effects of compensated turnout on dancers: a critical look at the leading cause of non-traumatic dance injuries Rachel Smith University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.utc.edu/honors-theses Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Rachel, "The psychosocial effects of compensated turnout on dancers: a critical look at the leading cause of non-traumatic dance injuries" (2018). Honors Theses. This Theses is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research, Creative Works, and Publications at UTC Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UTC Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Psychosocial Effects of Compensated Turnout on Dancers 1 The Psychosocial Effects of Compensated Turnout on Dancers: A Critical Look at the Leading Cause of Non-Traumatic Dance Injuries Rachel Smith Departmental Honors Thesis University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Department of Health and Human Performance Examination Date: March 22, 2018 ________________________________ ______________________________ Shewanee Howard-Baptiste Burch Oglesby Associate Professor of Exercise Science Associate Professor of Exercise Science Thesis Director Department Examiner ________________________________ Liz Hathaway Assistant Professor of Exercise -

Telomeres As Sentinels for Environmental Exposures, Psychological Stress, and Disease Susceptibility

Telomeres as Sentinels for Environmental Exposures, Psychosocial Stress, and Disease Susceptibility A Workshop Co-sponsored by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) and the National Institute on Aging (NIA) September 6-7, 2017 NIEHS Building 101 Rodbell Auditorium Research Triangle Park, NC Workshop Summary Revised November 21, 2017 This workshop summary was prepared by Samuel Thomas, Rose Li and Associates, Inc., under contract to the National Institute on Aging. The views expressed in this document reflect both individual and collective opinions of the workshop participants and not necessarily those of the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, or any organization represented by the workshop participants. Review of earlier versions of this meeting summary by the following individuals is gratefully acknowledged: Allison Aiello, Mary Armanios, Abraham Aviv, Susan Bailey, Linda Birnbaum, Stacy Drury, Elissa Epel, Michelle Heacock, Peter Lansdorp, Rose Li, Jue Lin, Belinda Needham, Lisbeth Nielsen, Patricia Opresko, Martin Picard, Chandra Reynolds, Janine Santos, Sharon Savage, Idan Shalev, Nancy Tuvesson, Pathik Wadhwa, Nan-ping Weng, and Danyelle Winchester. NIEHS-NIA Workshop on Telomeres September 6-7, 2017 Table of Contents Acronym Definitions ......................................................................................................................... iii Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... -

The Social-Psychological Outcomes of Dance Practice: a Review

DOI:10.2478/v10237-011-0067-ySport Science Review, vol. XX, No. 5-6, December 2011 The Social-Psychological Outcomes of Dance Practice: A Review Alexandros MALKOGEORGOS* • Eleni ZAGGELIDOU* Evagelos MANOLOPOULOS* • George ZAGGELIDIS* ance involvement among the youth has been described in many Dterms. Studies regarding the effects of dance practice on youth show different images. Most refer that dance enhanced personal and social opportunities, increased levels of socialization and characteristic behavior among its participants. Socialization in dance differs according to dance forms, and a person might become socialized into them not only in childhood and adolescence but also well into adulthood and mature age. The aim of the present review is to provide an overview of the major findings of studies concerning the social-psychological outcomes of dance practice. This review revealed that a considerable amount of researches has been conducted over the years, revealed positive social- psychological outcomes of dance practice, in a general population, as well as specifically for adults or for adolescents. According to dance form the typical personality profile of dancers, danc- ers being introverted, relatively high on emotionality, strongly achievement motivated and exhibiting less favorable self attitudes. It is proposed that a better understanding of the true nature of the social-psychological outcomes of dance practice can be provided if specific influential factors are taken into account in future research (i.e., participants’ characteristics, type of guidance, social context and structural qualities of the dance). Keywords: dance, youth, personality traits, socialization Introduction Dance can be performed at home or at a park, without any equipment, alone or in a group, is a choreographed routine of movements usually performed to music. -

Twyla Tharp Goes Back to the Bones

HARVARD SQUARED ture” through enchanting light displays, The 109th Annual dramatizes the true story of six-time world decorations, and botanical forms. Kids are Christmas Carol Services champion boxer Emile Griffith, from his welcome; drinks and treats will be available. www.memorialchurch.harvard.edu early days in the Virgin Islands to the piv- (November 24-December 30) The oldest such services in the country otal Madison Square Garden face-off. feature the Harvard University Choir. (November 16- Decem ber 22) Harvard Wind Ensemble Memorial Church. (December 9 and 11) https://harvardwe.fas.harvard.edu FILM The student group performs its annual Hol- The Christmas Revels Harvard Film Archive iday Concert. Lowell Lecture Hall. www.revels.org www.hcl.harvard.edu/hfa (November 30) A Finnish epic poem, The Kalevala, guides “A On Performance, and Other Cultural Nordic Celebration of the Winter Sol- Rituals: Three Films By Valeska Grise- Harvard Glee Club and Radcliffe stice.” Sanders Theatre. (December 14-29) bach. The director is considered part of Choral Society the Berlin School, a contemporary move- www.harvardgleeclub.org THEATER ment focused on intimate realities of rela- The celebrated singers join forces for Huntington Theatre Company tionships. She is on campus as a visiting art- Christmas in First Church. First Church www.huntingtontheatre.org ist to present and discuss her work. in Cambridge. (December 7) Man in the Ring, by Michael Christofer, (November 17-19) STAFF PICK:Twyla Tharp Goes music of Billy Joel), and, in 2012, the ballet based on George MacDonald’s eponymous tale The Princess and the Goblin. Back to the Bones Yet “Minimalism and Me” takes the audience back to New York City in the ‘60s and ‘70s, and the emergence of a rigor- Renowned choreographer Twyla Tharp, Ar.D. -

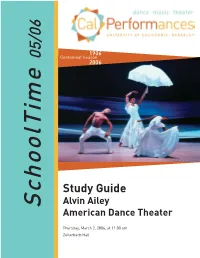

Alvinailey Study Guide 05 06.Indd

1906 05/06 Centennial Season 2006 Study Guide Alvin Ailey SchoolTime American Dance Theater Thursday, March 2, 2006, at 11:00 am Zellerbach Hall Welcome February 23, 2006 Dear Educator and Students, Welcome to SchoolTime! On Thursday, March 2, at 11:00 a.m., you will attend the SchoolTime performance of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. This study guide will help you prepare your students for their experience in the theater and give you a framework for how to integrate the performing arts into your curriculum. Targeted questions and activities will help students understand the context for Alvin Ailey’s world reknowned dance work, Revelations and provide an introduction to the art form of modern dance. Please feel free to copy any portion of this study guide. Study guides are also available online at http://cpinfo.berkeley.edu/information/education/study_guides.php. Your students can actively participate at the performance by: • OBSERVING the physical and mental discipline demonstrated by the dancers • LISTENING attentively to the music and lyrics of the songs chosen to accompany the dance • THINKING ABOUT how music, costumes and lighting contribute to the overall effect of the performance • REFLECTING on what they experienced at the theater after the performance We look forward to seeing you at the theater! Sincerely, Laura Abrams Rachel Davidman Director Education Programs Administrator Education & Community Programs About Cal Performances and SchoolTime The mission of Cal Performances is to inspire, nurture and sustain a lifelong appreciation for the performing arts. Cal Performances, the performing arts presenter and producer of the University of California, Berkeley, fulfi lls this mission by presenting, producing and commissioning outstanding artists, both renowned and emerging, to serve the University and the broader public through performances and education and community programs. -

January Workshops

January Workshops SATURDAY JANUARY 13TH “Manhattan Gets The Blues!” with Dexter Santos & Galit Weinfeld Learn about this historical dance through classes on vocabulary, movement technique, connection, musicality and more! 12p-2:30p: Section 1: “Blues Grooves” Level: Beginner (Prerequisite- Either a Blues Crash Course or Beginner Level Series Recommended) Get ready to level up your social dancing! We’ll be working on how to dance to different styles of Blues music, how to get that perfect Blues aesthetic, and some fun moves for you to throw down on the dance floor! 3p-5:30p: Section 2: “Blues, Your partner and You!” Level: Adv. Beginner/Intermediate (Prerequisite: Section 1, 2 months of Beginner Series or 1 month Intermediate Series.) Get ready to get fancy! We'll be focusing on partner conversation, lead and follow dynamics, styling and connecting with the music through rhythm and musicality. Pricing: Full Day-$60 In Adv / $70 Day Of; 1 Part Only - $35 in Adv / $40 Day Of ABOUT DEXTER SANTOS: With a background in Ballroom dancing and Lindy Hop, Dexter has studied and collaborated with the best Blues dance teachers and dancers making him one of the most sought-after and admired teachers in the national and international Blues dance scene. As a teacher, Dexter loves spreading his passion and joy for Blues dancing and aims to inspire dancers of all levels with the possi - bilities that this dance has to offer while preserving its roots, identity, and art form. Having taught in four conti - nents, Dexter's classes are known to be inspiring and fun, and are favorites at nationally and internationally renowned exchanges and workshops. -

By Barb Berggoetz Photography by Shannon Zahnle

Mary Hoedeman Caniaris and Tom Slater swing dance at a Panache Dance showcase. Photo by Annalese Poorman dAN e ero aNCE BY Barb Berggoetz PHOTOGRAPHY BY Shannon Zahnle The verve and exhilaration of dance attracts the fear of putting yourself out there, says people of all ages, as does the sense of Barbara Leininger, owner of Bloomington’s community, the sheer pleasure of moving to Arthur Murray Dance Studio. “That very first music, and the physical closeness. In the step of coming into the studio is sometimes a process, people learn more about themselves, frightening thing.” break down inhibitions, stimulate their Leininger has witnessed what learning to minds, and find new friends. dance can do for a bashful teenager; for a man This is what dance in Bloomington is who thinks he has two left feet; for empty all about. nesters searching for a new adventure. It is not about becoming Ginger Rogers or “It can change relationships,” she says. “It Fred Astaire. can help people overcome shyness and give “It’s getting out and enjoying dancing and people a new lease on life. People get healthier having a good time,” says Thuy Bogart, who physically, mentally, and emotionally. And teaches Argentine tango. “That’s so much they have a skill they can go out and have fun more important for us.” with and use for the rest of their lives.” The benefits of dancing on an individual level can be life altering — if you can get past 100 Bloom | April/May 2015 | magbloom.com magbloom.com | April/May 2015 | Bloom 101 Ballroom dancing “It’s really important to keep busy and keep the gears going,” says Meredith. -

Artist Bios Alex Katz Is the Author of Invented Symbols

Artist Bios Alex Katz is the author of Invented Symbols: An Art Autobiography. Current exhibitions include “Alex Katz: Selections from the Whitney Museum of American Art” at the Nassau County Museum of Art and “Alex Katz: Beneath the Surface” at the Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art. Jan Henle grew up in St. Croix and now works in Puerto Rico. His film drawings are in the collections of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, and The Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth. His collaborative film with Vivien Bittencourt, Con El Mismo Amor, was shown at the Gwang Ju Biennale in 2008 and is currently in the ikono On Air Festival. Juan Eduardo Gómez is an American painter born in Colombia in 1970. He came to New York to study art and graduated from the School of Visual Arts in 1998. His paintings are in the collections of the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick. He was awarded The Richard and Hilda Rosenthal Foundation Award from American Academy of Arts and Letters in 2007. Rudy Burckhardt was born in Basel in 1914 and moved to New York in 1935. From then on he was at or near the center of New York’s intellectual life, counting among his collaborators Edwin Denby, Paul Bowles, John Ashbery, Frank O’Hara, Kenneth Koch, Alex Katz, Red Grooms, Mimi Gross, and many others. His work has been the subject of exhibitions at the Instituto Valenciano de Arte Moderno, the Museum of the City of New York, and, in 2013, at Museum der Moderne Salzburg. -

Rhythmical Coordination of Performers and Audience in Partner Dance: Delineating Improvised and Choreographed Interaction

Rhythmical coordination of performers and audience in partner dance: delineating improvised and choreographed interaction Saul Albert ([email protected]) Contents 1 Introduction 3 2 Data and methods 4 2.1 Rhythm and interaction in a Lindy hop performance .................... 4 2.2 Studying the attention structure of an audience through rhythm ............... 6 2.3 Describing varied, coupled rhythms in the performance setting ............... 7 3 Analysis 9 3.1 Choreography: reorientation to familiar movements .................... 9 3.2 Improvisation: displays of readiness to change ....................... 13 3.3 Embodied action: joint coordination of improvised movement ................ 14 4 Discussion 17 4.1 Analytic distinctions between improvisation and choreography ............... 17 4.2 Embodied rhythms as projectable, interactional resources ................. 18 4.3 Embodied action built with non-vocal resources ...................... 19 5 Conclusion 21 6 Acknowledgements 21 7 References 21 1 Abstract This paper explores rhythm in social interaction by analysing how partner dancers and audience members move together during a performance. The analysis draws an empirical distinction between choreographed and improvised movements by tracking the ways participants deal with variations in the projectability and contingencies of upcoming movements. A detailed specification of temporal patterns and relationships between rhythms shows how different rhythms are used as interactional resources. Systematic disruptions to their rhythmical