Defining the Figure of the Welsh Witch, 1536-1736

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Handwriting, Abbreviations, Dates and More Dan Poffenberger, AG® British Research Specialist ~ Family History Library [email protected]

Understanding Handwriting, Abbreviations, Dates and More Dan Poffenberger, AG® British Research Specialist ~ Family History Library [email protected] Introduction Searching English records can be daunting enough when you are simply worrying about the time period, content and availability of records. A dive into a variety of records may leave you perplexed when you consider the handwriting styles, Latin, numbering systems, calendar changes, and variety of jurisdictions, record formats and abbreviations that may be found in the records. Objectives The objective of this course is to help you better understand: • Handwriting and Abbreviations • Latin • Numbers and Money • Calendars, Dates, Days, Years • Church of England Church Records Organization and Jurisdictions • Relationships Handwriting and Abbreviations Understanding the handwriting is the most important aspect to understanding older English records. If you can’t read it, you’re going to have a very hard time understanding it. While the term ‘modern English’ applies to any writing style after medieval times (late 1400’s), it won’t seem like it when you try reading some of it. More than 90% of your research will involve one of two primary English writing scripts or ‘hands’. These are ‘Secretary hand’ which was primarily in use from about 1525 to the mid-1600’s. Another handwriting style in use during that time was ‘Humanistic hand’ which more resembles our more modern English script. As secretary and humanistic hand came together in the mid-1600’s, English ‘round hand’ or ‘mixed hand’ became the common style and is very similar to handwriting styles in the 1900’s. But of course, who writes anymore? Round or Mixed Hand Starting with the more recent handwriting styles, a few of the notable differences in our modern hand are noted here: ‘d’ – “Eden” ‘f’ - “of” ‘p’ - “Baptized’ ss’ – “Edward Hussey” ‘u’ and ‘v’ – become like the ‘u’ and ‘v’ we know today. -

Unity in Diversity, Volume 2

Unity in Diversity, Volume 2 Unity in Diversity, Volume 2: Cultural and Linguistic Markers of the Concept Edited by Sabine Asmus and Barbara Braid Unity in Diversity, Volume 2: Cultural and Linguistic Markers of the Concept Edited by Sabine Asmus and Barbara Braid This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by Sabine Asmus, Barbara Braid and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5700-9, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5700-0 CONTENTS Introduction .............................................................................................. vii Cultural and Linguistic Markers of the Concept of Unity in Diversity Sabine Asmus Part I: Cultural Markers Chapter One ................................................................................................ 3 Questions of Identity in Contemporary Ireland and Spain Cormac Anderson Chapter Two ............................................................................................. 27 Scottish Whisky Revisited Uwe Zagratzki Chapter Three ........................................................................................... 39 Welsh -

Emotion, Seduction and Intimacy: Alternative Perspectives on Human Behaviour RIDLEY-DUFF, R

Emotion, seduction and intimacy: alternative perspectives on human behaviour RIDLEY-DUFF, R. J. Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/2619/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version RIDLEY-DUFF, R. J. (2010). Emotion, seduction and intimacy: alternative perspectives on human behaviour. Silent Revolution Series . Seattle, Libertary Editions. Repository use policy Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in SHURA to facilitate their private study or for non- commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Silent Revolution Series Emotion Seduction & Intimacy Alternative Perspectives on Human Behaviour Third Edition © Dr Rory Ridley-Duff, 2010 Edited by Dr Poonam Thapa Libertary Editions Seattle © Dr Rory Ridley‐Duff, 2010 Rory Ridley‐Duff has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Acts 1988. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution‐Noncommercial‐No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. Attribution — You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Noncommercial — You may not use this work for commercial purposes. -

Accused: Fairfield’S Witchcraft Trials September 25, 2014 – January 5, 2015 Educator Guide

Accused: Fairfield’s Witchcraft Trials September 25, 2014 – January 5, 2015 Educator Guide Accused: Fairfield’s Witchcraft Trials September 25, 2014 – January 5, 2015 Teacher Guide Index Introduction: The Legacy of Witchcraft Page 3 Essential Questions & Big Ideas Page 5 Accused Suggested Mini-Activity Page 6 Online Teacher Resources: Lesson Plans & Student Activities Page 7 Student & Teacher Resources: Salem Pages 9 - 10 New England Witchcraft Trials: Overview & Statistics Page 10 New England Witchcraft Timeline Pages 12 - 13 Vocabulary Page 14 Young Adult Books Page 15 Bibliography Page 15 Excerpts from Accused Graphic Novel Page 17 - 19 Educator Guide Introduction This Educator Guide features background information, essential questions, student activities, vocabulary, a timeline and a booklist. Created in conjunction with the exhibition Accused: Fairfield’s Witchcraft Trials, the guide also features reproductions of Jakob Crane’s original illustrations and storylines from the exhibition. The guide is also available for download on the Fairfield Museum’s website at www.fairfieldhistory.org/education This Educator Guide was developed in partnership with regional educators at a Summer Teacher Institute in July, 2014 and co-sponsored by the Fairfield Public Library. Participants included: Renita Crawford, Bridgeport, CT Careen Derise, Discovery Magnet School, Bridgeport, CT Leslie Greene, Side By Side, Norwalk, CT Lauren Marchello, Fairfield Ludlowe High School, Fairfield, CT Debra Sands-Holden, King Low Heywood Thomas School, Stamford, CT Katelyn Tucker, Shelton Public Schools, CT About the Exhibition: In 17th century New England religious beliefs and folk tradition instilled deep fears of magic, evil, and supernatural powers. How else to explain unnatural events, misfortune and the sudden convulsions and fits of local townspeople? In this exhibition, the fascinating history of Connecticut’s witchcraft trials is illuminated by author and illustrator Jakob Crane. -

The 400Th Anniversary of the Lancashire Witch-Trials: Commemoration and Its Meaning in 2012

The 400th Anniversary of the Lancashire Witch-Trials: Commemoration and its Meaning in 2012. Todd Andrew Bridges A thesis submitted for the degree of M.A.D. History 2016. Department of History The University of Essex 27 June 2016 1 Contents Abbreviations p. 3 Acknowledgements p. 4 Introduction: p. 5 Commemorating witch-trials: Lancashire 2012 Chapter One: p. 16 The 1612 Witch trials and the Potts Pamphlet Chapter Two: p. 31 Commemoration of the Lancashire witch-trials before 2012 Chapter Three: p. 56 Planning the events of 2012: key organisations and people Chapter Four: p. 81 Analysing the events of 2012 Conclusion: p. 140 Was 2012 a success? The Lancashire Witches: p. 150 Maps: p. 153 Primary Sources: p. 155 Bibliography: p. 159 2 Abbreviations GC Green Close Studios LCC Lancashire County Council LW 400 Lancashire Witches 400 Programme LW Walk Lancashire Witches Walk to Lancaster PBC Pendle Borough Council PST Pendle Sculpture Trail RPC Roughlee Parish Council 3 Acknowledgement Dr Alison Rowlands was my supervisor while completing my Masters by Dissertation for History and I am honoured to have such a dedicated person supervising me throughout my course of study. I gratefully acknowledge Dr Rowlands for her assistance, advice, and support in all matters of research and interpretation. Dr Rowland’s enthusiasm for her subject is extremely motivating and I am thankful to have such an encouraging person for a supervisor. I should also like to thank Lisa Willis for her kind support and guidance throughout my degree, and I appreciate her providing me with the materials that were needed in order to progress with my research and for realising how important this research project was for me. -

Ethical Record the Proceedings of the South Place Ethical Society

Ethical Record The Proceedings of the South Place Ethical Society Vol. 107 No. 1 £1.50 Jan-Feb, 2002 THE GENOCIDAL PRIMATE - A NOTE ON HOLOCAUST DAY When one sees how violent mankind has been, both to itself and to other species, it appears that, of the contemporary primate species, we have more in common with the spiteful meat-eating chimp than with the placid, vegetarian gorilla or the recently discovered, furiously promiscuous bonobo chimp. Our ancestors probably wiped out the Neanderthals in the course of their territorial disputes and with the final triumph of homo 'sapiens', rationalisations for genocide began to be invented (see the terrible 1 Sam. 15.3). Science tells us that human behaviour is the outcome of influences working throughout life on a plastic, gene-filled embryo. Now humanists are frequently expected, mistakenly in my view, to have faith in the natural goodness and inevitable progress of mankind. It would be more accurate however to believe in neither goodness nor evil as innate, embodied qualities. To be a humanist, it is sufficient to realise that we are each bound to justify our actions ourselves and, in strict logic, cannot defer our morality to any authority, real or imagined. The complicity of religious authorities in permitting agents of the Nazi genocidal machine to bear the 'Gott mit uns' (God is with Us) badge should be seen as an indelible blot on the ecclesiastical record. Death- camp inmates did well to ask 'Where is our God?' as their co-religionists choked in their Zyklon B 'showers'. To preserve the sentimental notion of a just God, some 'holocaust theologians' even stoop to blaming the victims. -

The Effect of Mobbing in Workplace on Professional Self-Esteem of Nurses

International Journal of Caring Sciences May-August 2018 Volume 11 | Issue 2| Page 1241 Original Article The Effect of Mobbing in Workplace on Professional Self-Esteem of Nurses Mine Cengiz Ataturk University Nursing Faculty, Psychiatric Nursing Department, Erzurum / Turkey Birsel Canan Demirbag Karadeniz Teknik University Faculty Of Health Sciences, Public Health Nursing Department, Trabzon, Turkey Osman Yiıldizlar Avrasya University Faculty Of Health Sciences, Health Management Department, Trabzon, Turkey Correspondence: Mine Cengiz, Ataturk University Nursing Faculty, Psychiatric Nursing Department, Erzurum, Turkey. [email protected] Abstract This study has been conducted to investigate the effect of mobbing (psychological violence) on professional self- esteem in nurses. This study has been carried out with 188 nurses participating voluntarily in the study at Erzurum Ataturk University Yakutiye Research Hospital between 19 March and 27 July 2016. For the collection of data, an introductory information form, Negative Acts Questionnaire-Revised (NAQ-R) and Professional Self- Esteem Scale (PSES) have been used. The data were analyzed by the SPSS program with mean, standard deviation, T-test, Mann Whitney U-test. In the results of the study, it has been determined that 55.9% of nurses were under 30 years old, 74.5% were female, 51.1% were married, 40.4% had undergraduate degrees, 70.2% were service nurses, 31.4% did nursing at the institution where they had been for 3-6 years, 79.8% were working 40 hours a week. It has been seen that 40.4% of the nurses are exposed to psychological violence, exposure to negative behavior is moderate ( x̅ = 34.61±12.99) and professional self-esteem is high ( x̅ = 104.92±17.27). -

Layout 1 Copy

STACK ROCK 2020 An illustrated guide to sea stack climbing in the UK & Ireland - Old Harry - - Old Man of Stoer - - Am Buachaille - - The Maiden - - The Old Man of Hoy - - over 200 more - Edition I - version 1 - 13th March 1994. Web Edition - version 1 - December 1996. Web Edition - version 2 - January 1998. Edition 2 - version 3 - January 2002. Edition 3 - version 1 - May 2019. Edition 4 - version 1 - January 2020. Compiler Chris Mellor, 4 Barnfield Avenue, Shirley, Croydon, Surrey, CR0 8SE. Tel: 0208 662 1176 – E-mail: [email protected]. Send in amendments, corrections and queries by e-mail. ISBN - 1-899098-05-4 Acknowledgements Denis Crampton for enduring several discussions in which the concept of this book was developed. Also Duncan Hornby for information on Dorset’s Old Harry stacks and Mick Fowler for much help with some of his southern and northern stack attacks. Mike Vetterlein contributed indirectly as have Rick Cummins of Rock Addiction, Rab Anderson and Bruce Kerr. Andy Long from Lerwick, Shetland. has contributed directly with a lot of the hard information about Shetland. Thanks are also due to Margaret of the Alpine Club library for assistance in looking up old journals. In late 1996 Ben Linton, Ed Lynch-Bell and Ian Brodrick undertook the mammoth scanning and OCR exercise needed to transfer the paper text back into computer form after the original electronic version was lost in a disk crash. This was done in order to create a world-wide web version of the guide. Mike Caine of the Manx Fell and Rock Club then helped with route information from his Manx climbing web site. -

Rule Britannia? Britain and Britishness 1707–1901

Rule Britannia? Britain and Britishness 1707–1901 Rule Britannia? Britain and Britishness 1707–1901 Edited by Peter Lindfield and Christie Margrave Rule Britannia? Britain and Britishness 1707–1901 Edited by Peter Lindfield and Christie Margrave This book first published 2015 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Peter Lindfield, Christie Margrave and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-7530-9 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-7530-1 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations .................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements .................................................................................... xi Peter Lindfield and Christie Margrave Introduction .............................................................................................. xiii Christie Margrave Part I: British Art and Design in the Promotion of National Identity Chapter One ................................................................................................. 3 National Identity through Design: the Anglicisation of the Rococo in Mid-Eighteenth-Century Britain Peter -

A Historical Approach to Assertiveness

Psychological Thought psyct.psychopen.eu | 2193-7281 Theoretical Analyses A Historical Approach to Assertiveness Ivelina Peneva*a, Stoil Mavrodieva [a] South-West University „Neofit Rilski”, Blagoevgrad, Bulgaria. Abstract A very important personal quality is to be able to advocate for yourself - your own positions, to achieve your objectives, to overcome difficulties, to be determined, but without harming the rights of others and to be able to control the aggressive impulses. The concept, which expresses these personal characteristics, is called "assertiveness". Assertiveness is a part of the personal potential. It is a prerequisite for self-actualization. The goal we set in this historical-psychological paper is to explore the genesis, development and stabilization of the term "assertiveness". In this context, we will examine, compare and analyze the positions of the leading authors on this issue. Keywords: assertive skills, assertive rights, assertiveness training, self-development Psychological Thought, 2013, Vol. 6(1), 3±26, doi:10.5964/psyct.v6i1.14 Received: 2012-04-12. Accepted: 2012-12-27. Published: 2013-04-30. *Corresponding author at: South-West University ªNeofit Rilskiº, 66, Ivan Mihailov Street, 2700 Blagoevgrad, Bulgaria. E-mail: [email protected] This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Introduction The beginning of the experimental study of assertiveness commenced in the middle of last century and it was related to clinical practice. Beck, Freeman, and Davis (2004), Lazarus (1971), Salter (2002), Ullrich and Ullrich de Muynck (1973), Wolpe (1990) and others worked in this area. -

Chapter VIII Witchcraft As Ma/Efice: Witchcraft Case Studies, the Third Phase of the Welsh Antidote to Witchcraft

251. Chapter VIII Witchcraft as Ma/efice: Witchcraft Case Studies, The Third Phase of The Welsh Antidote to Witchcraft. Witchcraft as rna/efice cases were concerned specifically with the practice of witchcraft, cases in which a woman was brought to court charged with being a witch, accused of practising rna/efice or premeditated harm. The woman was not bringing a slander case against another. She herself was being brought to court by others who were accusing her of being a witch. Witchcraft as rna/efice cases in early modem Wales were completely different from those witchcraft as words cases lodged in the Courts of Great Sessions, even though they were often in the same county, at a similar time and heard before the same justices of the peace. The main purpose of this chapter is to present case studies of witchcraft as ma/efice trials from the various court circuits in Wales. Witchcraft as rna/efice cases in Wales reflect the general type of early modern witchcraft cases found in other areas of Britain, Europe and America, those with which witchcraft historiography is largely concerned. The few Welsh cases are the only cases where a woman was being accused of witchcraft practices. Given the profound belief system surrounding witches and witchcraft in early modern Wales, the minute number of these cases raises some interesting historical questions about attitudes to witches and ways of dealing with witchcraft. The records of the Courts of Great Sessions1 for Wales contain very few witchcraft as rna/efice cases, sometimes only one per county. The actual number, however, does not detract from the importance of these cases in providing a greater understanding of witchcraft typology for early modern Wales. -

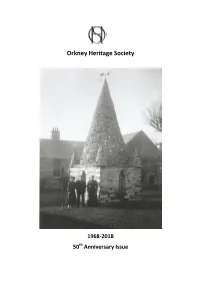

2018 50Th Anniversary Issue

Orkney Heritage Society 1968-2018 50th Anniversary Issue Objectives of the Orkney Heritage Society The aims of the Society are to promote and encourage the following objectives by charitable means: 1. To stimulate public interest in, and care for the beauty, history and character of Orkney. 2. To encourage the preservation, development and improvement of features of general public amenity or historical interest. 3. To encourage high standards of architecture and town planning in Orkney. 4. To pursue these ends by means of meetings, exhibitions, lectures, conferences, publicity and promotion of schemes of a charitable nature. New members are always welcome To learn more about the society and its ongoing work, check out the regularly updated website at www.orkneycommunities.co.uk/ohs or contact us at Orkney Heritage Society PO Box No. 6220 Kirkwall Orkney KW15 9AD Front Cover: Robert Garden and his wife, Margaret Jolly, along with one of their daughters standing next to the newly re-built Groatie Hoose. It got its name from the many shells, including ‘groatie buckies’, decorating the tower. Note the weather vane showing some of Garden’s floating shops. Photo gifted by Mrs Catherine Dinnie, granddaughter of Robert Garden. 1 Orkney Heritage Society Committee 2018 President: Sandy Firth, Edan, Berstane Road, Kirkwall, KW15 1NA [email protected] Vice President: Sheena Wenham, Withacot, Holm [email protected] Chairman: Spencer Rosie, 7 Park Loan, Kirkwall, KW15 1PU [email protected] Vice Chairman: David Murdoch, 13