Homosociality and the Early Beatles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George Harrison

COPYRIGHT 4th Estate An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.4thEstate.co.uk This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2020 Copyright © Craig Brown 2020 Cover design by Jack Smyth Cover image © Michael Ochs Archives/Handout/Getty Images Craig Brown asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins. Source ISBN: 9780008340001 Ebook Edition © April 2020 ISBN: 9780008340025 Version: 2020-03-11 DEDICATION For Frances, Silas, Tallulah and Tom EPIGRAPHS In five-score summers! All new eyes, New minds, new modes, new fools, new wise; New woes to weep, new joys to prize; With nothing left of me and you In that live century’s vivid view Beyond a pinch of dust or two; A century which, if not sublime, Will show, I doubt not, at its prime, A scope above this blinkered time. From ‘1967’, by Thomas Hardy (written in 1867) ‘What a remarkable fifty years they -

John Lennon – Człowiek I Artysta Niespełniony?

Tom 12/2020, ss. 43-72 ISSN 0860-5637 e-ISSN 2657-7704 DOI: 10.19251/rtnp/2020.12(3) www.rtnp.mazowiecka.edu.pl Andrzej Dorobek Mazowiecka Uczelnia Publiczna w Płocku ORCID: 0000-0002-5102-5182 JOHN LENNON – CZŁOWIEK I ARTYSTA NIESPEŁNIONY? JOHN LENNON: A MAN AND ARTIST UNFULFIILLED? Streszczenie: Niniejszy esej jest próbą syntetycznego, poniekąd psychoanalitycznego, ujęcia biografii Johna Lennona, zarówno jako ewidentnie zagubionego geniu- sza muzyki popularnej, jak i ofiary chłopięcego kompleksu zaniedbania przez uwielbianą matkę – później wysublimowanego w kompleks kobiecej dominacji i przeniesionego na Yoko Ono, jego drugą żonę i awangardową „muzę.” W re- zultacie ich związek, w znacznym stopniu wyidealizowany przez media, został ukazany w kontekście relacji Lennona z innymi kobietami (na przykład z ciotką Mimi), sprzecznych cech jego osobowości oraz ewolucji światopoglądowej i ar- tystycznej, która doprowadziła najpierw do dramatycznego rozdarcia między popowym supergwiazdorstwem a awangardowym artystostwem, ostatecznie zaś – do faktycznej niemocy twórczej w ciągu ostatnich pięciu lat życia. Per- John Lennon – człowiek i artysta niespełniony? spektywę komparatystyczną dla tych rozważań wyznaczać będą biografie Elvisa Presleya i Micka Jaggera. Słowa kluczowe: kompleks, trauma, dominacja, „krzyk pierwotny”, gwiaz- dorstwo, artyzm, niespełnienie Summary: In this essay, the author attempts at a synthetic insight into the biography of John Lennon, both as a confused genius of popular music and a victim of the childhood complex of motherly neglect: later transformed into the one of female domination and transferred onto Yoko Ono, his second wife and avant-garde “muse.” Consequently, their marriage, largely idealized by media, is shown here in the context of Lennon’s relations with other women (mainly his mother and aunt Mimi), his contradictory psychological traits and artistic/ ideological evolution that resulted in being torn between pop superstardom, avant-garde artistry and, in last five years, virtual creative impotence. -

International Beatleweek Fab Facts

International Beatleweek Fab Facts 1. International Beatleweek is worth an estimated £2.8m to the local economy. Cavern City Tours alone books around 4,500 bed nights with city hotels for the August Bank Holiday week. 2. The first Beatles Convention was held at Mr Pickwick’s club in 1977 and was organised by legendary Cavern Club DJ Bob Wooler and the Beatles’ first manager Allan Williams. It has been held at the Adelphi Hotel every year since 1981, apart from 1984 when it moved to St George’s Hall. 3. Since its inception, International Beatleweek has welcomed in the region of 900 different bands, artists and guests to its stages from 50 different countries including Guatemala, Thailand and Kazakhstan. 4. The 2010 Peace, Love & Understanding concert, held in Liverpool’s majestic Anglican Cathedral, featured performances by bands or artists from all seven continents including Antarctica, from which Trinity Church performed Let It Be. 5. The youngest performer at Beatleweek is three-year-old American Walter Bolin who sang on stage with his parents Eli Bolin and Allison Posner in 2017. The youngest official band in the history of International Beatleweek is The Beatbrothers, whose members Phil and Eddie Gillespie appeared at the Cavern in 2001 at the ages of eleven and nine respectively. 6. The Cavern Club welcomes around 10,000 visitors during Beatleweek. 7. The festival has led to romance. There have been two proposals on stage during recent years, while one marriage to come out of Beatleweek involved a member of the security team and an American Beatle fan he met and fell in love with at the 1989 event. -

The Beatles on Film

Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 1 ) T00_01 schmutztitel - 885.p 170758668456 Roland Reiter (Dr. phil.) works at the Center for the Study of the Americas at the University of Graz, Austria. His research interests include various social and aesthetic aspects of popular culture. 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 2 ) T00_02 seite 2 - 885.p 170758668496 Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film. Analysis of Movies, Documentaries, Spoofs and Cartoons 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 3 ) T00_03 titel - 885.p 170758668560 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Universität Graz, des Landes Steiermark und des Zentrums für Amerikastudien. Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de © 2008 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Layout by: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Edited by: Roland Reiter Typeset by: Roland Reiter Printed by: Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar ISBN 978-3-89942-885-8 2008-12-11 13-18-49 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02a2196899938240|(S. 4 ) T00_04 impressum - 885.p 196899938248 CONTENTS Introduction 7 Beatles History – Part One: 1956-1964 -

A History of International Beatleweek (PDF)

The History of International Beatleweek International Beatleweek celebrates the most famous band in the world in the city where it was born – attracting thousands of Fab Four fans and dozens of bands to Liverpool each year. The history of Beatleweek goes back to 1977 when Liverpool’s first Beatles Convention was held at Mr Pickwick’s club in Fraser Street, off London Road. The two-day event, staged in October, was organised by legendary Cavern Club DJ Bob Wooler and Allan Williams, entrepreneur and The Beatles’ early manager, and it included live music, guest speakers and special screenings. In 1981, Liz and Jim Hughes – the pioneering couple behind Liverpool’s pioneering Beatles attraction, Cavern Mecca – took up the baton and arranged the First Annual Mersey Beatle Extravaganza at the Adelphi Hotel. It was a one-day event on Saturday, August 29 and the special guests were Beatles authors Philip Norman, Brian Southall and Tony Tyler. In 1984 the Mersey Beatle event moved to St George’s Hall where guests included former Cavern Club owner Ray McFall, Beatles’ press officer Tony Barrow, John Lennon’s uncle Charles Lennon and ‘Father’ Tom McKenzie. Cavern Mecca closed in 1984, and after the city council stepped in for a year to keep the event running, in 1986 Cavern City Tours was asked to take over the Mersey Beatle Convention. It has organised the annual event ever since. International bands started to make an appearance in the late 1980s, with two of the earliest groups to make the journey to Liverpool being Girl from the USA and the USSR’s Beatle Club. -

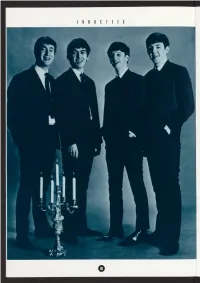

On John Lennon's Music

“She Said She Said” – The Influence of "Feminine Voices" on John Lennon’s Music (1) John Lennon’s songs show the recurrent influence of female voices, and this can be shown by musicological comparisons of Lennon compositions with earlier songs sung by women, which he was familiar with. Some of these resemblances have already been pointed out; others are discussed here for the first time. Although these influences featured throughout Lennon’s work, we will focus on the early Beatles (1958-1963), and how specific songs, mostly US R&B, influenced Lennon’s songwriting (he wrote in partnership with Paul McCartney, but it is possible to establish the balance of their contributions by reference to secondary literature, eg Miles 1997, Sheff and Golson 1982, MacDonald 2005). (2) In the period 1958-1963 the Beatles developed from a covers band into the most famous popular music group in the world. The group were constantly listening for new material (they had a huge repertoire of covers), and were absorbing and experimenting with different musical styles in response to increasingly feminised audiences. They initially saw their songwriting as addressing a primarily female audience (Lewisohn 2013). Moreover, almost all the works featuring woman’s voices identified in Lennon’s work come from this period. (3) Lennon, by most accounts, was the “macho” Beatle and was occasionally violent towards women, so it seems surprising that he led the way in covering and borrowing from songs sung by women, most particularly, early 60s US girl-groups such as The Shirelles, the Marvelettes and The Cookies. (4) Most accounts of the Beatles' influences emphasise male artists such as Elvis Presley, Little Richard, Buddy Holly and Chuck Berry (Dafydd, Crampton 1996, 4; Gould 2007, 58–68). -

The Last Days of John Lennon

Copyright © 2020 by James Patterson Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce creative works that enrich our culture. The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights. Little, Brown and Company Hachette Book Group 1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104 littlebrown.com twitter.com/littlebrown facebook.com/littlebrownandcompany First ebook edition: December 2020 Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher. The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591. ISBN 978-0-316-42907-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2020945289 E3-111020-DA-ORI Table of Contents Cover Title Page Copyright Dedication Prologue Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 — Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Chapter 18 — Chapter 19 Chapter 20 Chapter 21 Chapter 22 Chapter 23 Chapter 24 -

Rise of the Robots | Cancer Doctor | 04/2014 HIS April/May 2014 INVESTIGATEMAGAZINE.COM 49

HERS Fluoride & IQ & Fluoride | Rise Of The Robots The Of Rise | current affairs and lifestyle Cancer Doctor Cancer for the discerning woman | 04/2014 THE CHEMICAL THAT CAN LOWER YOUR BABY’S IQ And why bottled milk formula may be delivering harmful doses of it THE REDEMPTION OF SHANE JONES He could still be Labour’s next Prime Minister A CURE FOR CANCER? 04/2014 A controversial doctor with NZ links gets | permission to continue experiments April/May 2014 Defence Cuts Defence | RISE OF THE ROBOTS Sexbots, Searchbots, Milbots and Western Decline Western | Homebots – are we the ‘Jetsons’ yet? Shane Jones Shane PLUS in HIS: MARK STEYN AMY BROOKE DAVID GARRETT & MORE HIS April/May 2014 INVESTIGATEMAGAZINE.COM 49 publiceye-INVES6014 CONTENTS Issue 143 | April/May 2014 | www.investigatedaily.com features Fluoride & IQ It’s the chemical that could be dumbing down our kids: fluoridated water used to make infant formula takes babies over the maximum poison limit, 93% of the time. IAN WISHART reveals more about the fluoride debate page 10 Rise Of Robots Once the stuff of science fiction, robots are everywhere these days, in factories and even some homes. What does the future hold, and should we be worried? page 16 April/May 2014 INVESTIGATEMAGAZINE.COM 1 CONTENTS Formalities 04 Miranda Devine 06 Martin Walker 08 Chloe Milne Health & Beauty 26 Diet temptations 28 Varicose veins 34 Gettin’ wiggy with it 26 Cuisine & Travel 36 James Morrow on Spaghetti 38 Beatles’ Liverpool 36 Books & Movies 40 Michael Morrissey 42 Single Moms Club Home & Family 44 Pre-marital sex 46 Career aspirations 34 46 42 HERS / DEVINE The truth about John Howard had emptied boat people out the Miranda Devine detention young man came to our doorstep seeking our centres. -

Für Sonntag, 21

BeatlesInfoMail (wöchentlich): 19.07.20: BEATLES-Angebote /// BEATLES-Termine /// BEATLES-Magazin THINGS ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- BeatlesInfoMail (wöchentlich): Sonntag 19. Juli 2020 Termine / Beatles-Magazin THINGS / MANY YEARS AGO / Angebote für M.B.M.s und Fans, denen wir die täglichen und wöchentlichen BeatlesInfoMails zuschicken dürfen InfoMails verschicken wir auf Wunsch an alle, deren E-Mail-Adresse vorliegt. täglich = alle Neuerscheinungen und alle Angebote / wöchentlich = Termine und einige Angebote / monatlich = die wöchentliche SonntagsInfoMail zum Monatswechsel. Wichtig ist uns, dass wir in Kontakt bleiben - also bitte ab und zu melden. Bei länger zurückliegenden Kontakten, melden wir uns nur noch wöchentlich oder monatlich. Alter Markt 12, 06108 Halle (Saale); Telefon / phone: 0345-2903900 / WhatsApp 0179-4284122 / Fax: 0345-2903908 E-Mail: [email protected] / Internet: www.BeatlesMuseum.net Geöffnet: dienstags bis sonntags und an Feiertagen (außer Weihnachten und Jahreswechsel) jeweils 10.00 bis 18.00 Uhr (nach Absprache auch später - oder morgens früher) Zusätzliche Öffnungszeiten für Gruppen und Schulklassen auf Anfrage; auch abends. Geschlossen: Heiligabend/Weihnachten und Silvester/Neujahr. Betrachte diese InfoMail (wie alle anderen auch) also auch als einen Info-Service vom Beatles Museum! Und wenn wir Dir ab und zu mal etwas zuschicken dürfen - bestens!! Und wenn wir Dir bereits unser Beatles-Magazin zuschicken oder künftig zuschicken dürfen - allerbestens!!! _______________________________________________________________________________________________ Gliederung der WochenInfoMail: 1. Die „Top 4“-BEATLES-Angebote 2. Termine für BEATLES-Interessierte 2a: BEATLES-Stammtische / 2b: Termine von Tribute-Bands / 2c: Termine - Konzerte, Veranstaltungen etc. 3. BEATLES-Magazin THINGS vom Beatles Museum 4. MANY YEARS AGO: Was geschah heute vor X Jahren? 5. Aktuelle Veröffentlichungen im Jahr 2020 und weitere 6. -

The Beatles.Pdf

KOCK HOD ROIL 1 HALL OL LAME The Beatles istorically s p e a k i n g , t h e b i r t h o f t h e Be a t l e s h a s b e e n group to the paper: "Many people ask what are Beades? Why, Beades? Ugh, traced time and again to Saturday afternoon, July 6th, 1957, at the Beades, how did the name arrive? So we will tell you. It came in a vision - a S t Peter’s parish garden fete in Woolton, a Liverpool suburb. Sev- man appeared on a flaming pie and said tinto diem, 'From this day on you are enteen-year-old John Lennon was performing there with a group of Beades.’ 'Thank you, Mister Man,’ they said, thanking him.” school chums who called themselves the Quarrymen. They were a T he Beades also caught the eye o f influential locals like the D J Bob Wooler, product of the skiffle craze - a fad inspired by the primitive wash who convinced Ray McFall, owner of die Cavern dub, to book die combo. In board-band sound of Lonnie Donegan’s hit "Rock Island Line” — but theyJuly 1961 the Beades, reduced to a four-piece when Sutcliffe returned to Ham displayedH a pronounced rock and roll bent. Watching the Quarrymen was burg to paint and be with his girlfriend, commenced their legendary lunch-time fifteen-year-old guitarist Paul McCartney, who was introduced to the band cpccinns at the Cavern. That’s where a curious Brian Epstein, a record mer afterward. -

KLOS Mothers Day 2013

1 PLAYLIST MOTHERS DAY 2013 1 2 9AM Plastic Ono Band - Mother – Plastic Ono Band sessions `70 Started in England and finished in LA during his infamous Primal Scream Therapy from Dr. Arthur Janov in the summer of 1970 John Lennon’s Mother - Julia The Beatles – Let It Be – Let It Be…Naked 2 3 Written after a dream about his Mother speaking to Paul for the first time in quite a while…she passed away when he was 14. Mary McCartney A song linked to a Beatle Mom/… Beatle Mom’s: Louise Harrison Mary McCartney Julia Lennon Elsie Starkey 3 4 The Beatles – Julia – The Beatles Only part about John’s mother Julia but also mentions his then girlfriend Yoko Ono with the references to “Ocean Child” which in Japanese means….YOKO George Harrison – Deep Blue – flip Bangla Desh Single Written during the All Things Must Pass sessions for his Mom who passed away on July 7, 1970. The Beatles – I Lost My Little Girl – Unplugged Paul wrote this just after his Mother Mary had died, and he later explained that it was a subconscious reference her. Ringo Starr – Stardust – Sentimental Journey Arranged by Paul McCartney. Hoagy Carmichael wrote the tune in 1927, with the words added in 1929. Ringo was familiar with the 1957 hit version by Billy Ward and the Dominoes…you thought Eric Clapton was the first to have dominos Up next a few songs written about Beatle Wives who are Mom’s… on this Mother’s Day morning… Linda’s 1st song/The Beatles – I Will – The Beatles… Yoko /John Lennon – Woman – Double Fantasy (John) QUIZ #1 HERE Now since we don’t have a Ringo song about the mother of his offspring …I have a quiz question for you…. -

To Rudolf Frieling

To Rudolf Frieling 8 November 2014 Granby TriangleImage courtesy Charlotte Horn Rudolf Frieling San Francisco, USA San Francisco, USA 8 November 2014 R Thanks for your invitation to write something short about Candice Breitz’s Working Class Hero (A Portrait of John Lennon), the piece we have at SFMOMA. You know, my first art-related job was in Liverpool. I once taught a course in Minimalism and Pop Art in the art department of Liverpool John Moores University (Liverpool College of Art, it used to be called), the school where, decades earlier, John Lennon studied. Lennon, aged seventeen, enrolled in September 1957, a month before he and Paul McCartney shared a stage for the first time. Paul was fifteen; his high school adjoined the college. I was back in Liverpool recently and took a different kind of tour – one led by artists and activists who are engaged with the housing crisis in the city. They’re fighting the alliance between government and business that’s dismantling the remaining working-class neighbourhoods. It’s said that the old terraces are worth more as bricks in London than they are as houses in Liverpool — one city is consuming the other. The tour began at the former Park Palace theatre, where John Lennon’s mother, Julia, often saw movies. She was killed in a car accident in 1958. The Park Palace closed in 1959, became a pharmacy, then a vehicle repair shop, then it fell into disuse. Our tour later stopped at the Empress pub, where John and Ringo used to drink. Mural portraits of the two of them are in alcoves high up on the facade.