Frequently Asked Questions (Faqs) About the Multidimensional Poverty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Determinants of Multidimensional Poverty Index of Niger State, Nigeria

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 1 1 , No. 14, Contemporary Business and Humanities Landscape Towards Sustainability. 2021, E-ISSN: 2222-6990 © 2021HRMARS Determinants of Multidimensional Poverty Index of Niger State, Nigeria Musa Mohammed, Rossazana Ab-Rahim To Link this Article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v11-i14/8532 DOI:10.6007/IJARBSS/v11-i14/8532 Received: 29 November 2020, Revised: 25 December 2020, Accepted: 18 January 2021 Published Online: 30 January 2021 In-Text Citation: (Mohammed & Ab-Rahim, 2021) To Cite this Article: Mohammed, M., & Ab-Rahim, R. (2021). Determinants of Multidimensional Poverty Index of Niger State, Nigeria. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 11(14), 95– 108. Copyright: © 2021 The Author(s) Published by Human Resource Management Academic Research Society (www.hrmars.com) This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at: http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode Special Issue: Contemporary Business and Humanities Landscape Towards Sustainability, 2021, Pg. 95 – 108 http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/IJARBSS JOURNAL HOMEPAGE Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/publication-ethics 95 International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 1 1 , No. 14, Contemporary Business and Humanities Landscape Towards Sustainability. -

Measuring the Inequality of Well-Being: the Myth Of

Measuring the Inequality of Well-being: The Myth of “Going beyond GDP” By Lauri Peterson Submitted to Central European University Department of International Relations and European Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Thomas Fetzer Word count: 15,987 CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2013 Abstract The last decades have seen a surge in the development of indices that aim to measure human well-being. Well-being indices (such as the Human Development Index, the Genuine Progress Indicator and the Happy Planet Index) aspire to go beyond the standard growth-based economic definitions of human development (“go beyond GDP”), however, this thesis demonstrates that this is not always the case. The thesis looks at the methods of measuring the distributional aspects of human well-being. Based on the literature five clusters of inequality are developed: economic inequality, educational inequality, health inequality, gender inequality and subjective inequality. These types of distribution have been recognized to receive the most attention in the scholarship of (in)equality measurement. The thesis has discovered that a large number of well-being indices are not distribution- sensitive (do not account for inequality) and indices which are distribution-sensitive primarily account for economic inequality. Only a few indices, such as the Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index, the Gender Inequality Index, the Global Gender Gap and the Legatum Prosperity Index are sensitive to non-economic inequality. The most comprehensive among the distribution-sensitive well-being indices that go beyond GDP is the Inequality Adjusted Human Development Index which accounts for the inequality of educational and health outcomes. -

Measuring Human Development and Human Deprivations Suman

Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative (OPHI) Oxford Department of International Development Queen Elizabeth House (QEH), University of Oxford OPHI WORKING PAPER NO. 110 Measuring Human Development and Human Deprivations Suman Seth* and Antonio Villar** March 2017 Abstract This paper is devoted to the discussion of the measurement of human development and poverty, especially in United Nations Development Program’s global Human Development Reports. We first outline the methodological evolution of different indices over the last two decades, focusing on the well-known Human Development Index (HDI) and the poverty indices. We then critically evaluate these measures and discuss possible improvements that could be made. Keywords: Human Development Report, Measurement of Human Development, Inequality- adjusted Human Development Index, Measurement of Multidimensional Poverty JEL classification: O15, D63, I3 * Economics Division, Leeds University Business School, University of Leeds, UK, and Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI), University of Oxford, UK. Email: [email protected]. ** Department of Economics, University Pablo de Olavide and Ivie, Seville, Spain. Email: [email protected]. This study has been prepared within the OPHI theme on multidimensional measurement. ISSN 2040-8188 ISBN 978-19-0719-491-13 Seth and Villar Measuring Human Development and Human Deprivations Acknowledgements We are grateful to Sabina Alkire for valuable comments. This work was done while the second author was visiting the Department of Mathematics for Decisions at the University of Florence. Thanks are due to the hospitality and facilities provided there. Funders: The research is covered by the projects ECO2010-21706 and SEJ-6882/ECON with financial support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Technology, the Junta de Andalucía and the FEDER funds. -

Quantitative Comparisons of Economic Systems

Lecture 3: Quantitative Comparisons of Economic Systems Prof. Paczkowski Rutgers University Fall, 2007 Prof. Paczkowski (Rutgers University) Lecture 3: Quantitative Comparisons of Economic Systems Fall, 2007 1 / 87 Part I Assignments Prof. Paczkowski (Rutgers University) Lecture 3: Quantitative Comparisons of Economic Systems Fall, 2007 2 / 87 Assignments W. Baumol, et al. Good Capitalism, Bad Capitalism Available at http://www.yalepresswiki.org/ Prof. Paczkowski (Rutgers University) Lecture 3: Quantitative Comparisons of Economic Systems Fall, 2007 3 / 87 Assignments Research and learn as much as you can about the following: Real GDP Human Development Index Gini Coefficient Corruption Index World Population Growth Human Poverty Index Quality of Life Index Reporters without Borders Be prepared for a second Group Teach on these after the midterm: October 24 Prof. Paczkowski (Rutgers University) Lecture 3: Quantitative Comparisons of Economic Systems Fall, 2007 4 / 87 Part II Introduction Prof. Paczkowski (Rutgers University) Lecture 3: Quantitative Comparisons of Economic Systems Fall, 2007 5 / 87 Comparing Economic Systems How do we compare economic systems? We previously noted the many qualitative ways of comparing economic systems { organization, incentives, etc What about the quantitative? Potential quantitative measures might include Real GDP level and growth Population level and growth Income and wealth distribution Major financial and industrial statistics Indexes of freedom and corruption These measures should tell a story The story is one of economic performance Prof. Paczkowski (Rutgers University) Lecture 3: Quantitative Comparisons of Economic Systems Fall, 2007 6 / 87 Comparing Economic Systems (Continued) Economic performance is multifaceted Judging how an economic system performs, we can look at broad topics or issues such as.. -

CHAPTER 02 LITERATURE REVIEW on PROSPERITY INDICATORS 2.1 Introduction a Healthy, Wealthy and Happy People Constitute a Prospero

CHAPTER 02 LITERATURE REVIEW ON PROSPERITY INDICATORS 2.1 Introduction A healthy, wealthy and happy people constitute a prosperous nation. The term prosperity has a wider meaning: enhancement of the quality of life of people through sustainable wealth creation and inclusion of all segments of the society in enjoying the benefits of development for which an inalienable pre requisite is the balanced regional development (Somapala, 2008). Accurately assessing the wellbeing of an entire society is no simple matter, as tempting to focus on purely financial measures, which have become easily available in recent years. But if we take the life satisfaction into account, we should consider a broader concept, which is known as prosperity (Legatum Institute, 2011). Many countries have developed prosperity indicators specific to their social, political and economical context. 2.1.1 Principles of prosperity According to the Legatum Institute (2011) there are general principles relevant to the promotion of national prosperity. These are: • Freedom of choice is crucial • For very poor countries, raising incomes is the first priority • Money matters to people, but only up to a point • Growth in invested capital is the strongest driver of long term economic growth 6 • Dependence on foreign development aid reduces long term growth rates • Open economies in which foreign direct investment and international trade play larger roles have higher long term growth rates • Lower costs of bureaucracy increase economic growth rates (Legatum Institute, 2011) 2.2 Economic Development. Economic development is defined as the development of economy of countries or regions for the well-being of their inhabitants. It is the process by which a nation improves the economic, political, and social well being of its people. -

Multidimensional Poverty Index Sen, A

Development Strategy and Policy Analysis Unit w Development Policy and Analysis Division Department of Economic and Social Affairs Multidimensional Poverty Development Issues No. 3 21 October 2015 The measurement of poverty is composed of two fundamental steps, according to Amartya Sen (1976): determining who is Summary poor (identification) and building an index to reflect the extent of poverty (aggregation). Both steps have been sources of debate Measuring poverty with a single income or expenditure over time among academics and practitioners. For a long time, measure is an imperfect way to understand the deprivations unidimensional measures were used to distinguish poor from of the poor since, for example, markets for basic needs and non-poor. More recently, new measures have been proposed to public goods may not exist. Complementing monetary enrich the understanding of socio-economic conditions and to with non-monetary information provides a more complete better reflect the evolving concept of poverty. picture of poverty. From unidimensional to multi- dimensional poverty assesses human deprivation in terms of shortfalls from minimum Poverty measurement has primarily used income for the iden- levels of basic needs per se, instead of using income as an interme- tification of the poor since the early twentieth century. In the diary of basic needs satisfaction. The reasoning for this relies on 1950s, economic growth and macroeconomic policies domi- the argument that, while an increase in purchasing power allows nated the development discourse, which meant little attention the poor to better achieve their basic needs, markets for all basic was paid to the difficulties faced by poor people (ODI, 1978). -

Beyond Monetary Poverty 4

Beyond Monetary Poverty 4 This chapter reports on the results of the World Bank’s first exercise of multidimensional global poverty measurement. Information on income or consumption is the traditional basis for the World Bank’s poverty estimates, including the estimates reported in chapters 1–3. However, in many settings, important aspects of well-being, such as access to quality health care or a secure community, are not captured by standard monetary measures. To address this concern, an established tradition of multidimensional poverty measurement measures these nonmone- tary dimensions directly and aggregates them into an index. The United Nations Development Programme’s Multidimensional Poverty Index (Global MPI), produced in conjunction with the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative, is a foremost example of such a multi- dimensional poverty measure. The analysis in this chapter complements the Global MPI by placing the monetary measure of well-being alongside nonmonetary dimensions. By doing so, this chapter explores the share of the deprived population that is missed by a sole reliance on monetary poverty as well as the extent to which monetary and nonmonetary deprivations are jointly presented across different contexts. The first exercise provides a global picture using comparable data across 119 countries for circa 2013 (representing 45 percent of the world’s population) combining consumption or income with measures of education and access to basic infrastructure services. Accounting for these aspects of well-being alters the perception of global poverty. The share of poor increases by 50 percent—from 12 percent living below the international poverty line to 18 percent deprived in at least one of the three dimensions of well-being. -

Poverty Measures

Poverty and Vulnerability Term Paper Interdisciplinary Course International Doctoral Studies Programme Donald Makoka, (ZEF b) Marcus Kaplan, (ZEF c) November 2005 ABSTRACT This paper describes the concepts of poverty and vulnerability as well as the interconnections and differences between these two. Vulnerability is a multi-dimensional phenomenon, because it can be related to very different kinds of hazards. Nevertheless most studies deal with the vulnerability to natural disasters, climate change, or poverty. As a result of the effects of global change, vulnerability focuses more and more on the livelihood of the affected people than on the hazard itself in order to enhance their coping capacities to the negative effects of hazards. Thus the concept became quite complex, and we present some approaches that try to deal with this complexity. In contrast to poverty, vulnerability is a forward-looking feature. Thus vulnerability and poverty are not the same. Nevertheless they are closely interrelated, as they influence each other and as very often poor people are the most vulnerable group to the negative effects of any type of hazard. There are also attempts to measure the vulnerability to fall below the poverty line, which is mostly done through income measurements. This paper therefore reviews the major linkages between poverty and vulnerability. Different measures of poverty, both quantitative and qualitative are presented. The three different forms of vulnerability namely, to natural disasters, climate and economic shocks, are discussed. The paper further evaluates different methods of measuring vulnerability, each of which employs unique and/or different parameters. Two case studies from Malawi and Europe are discussed with the conclusion that poverty and vulnerability, though not synonymous, are highly related. -

Piecing Together the Poverty Puzzle

PIECING TOGETHER THEPOVERTY PUZZLE PIECING TOGETHER THEPOVERTY PUZZLE © 2018 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved 1 2 3 4 21 20 19 18 This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The fi ndings, interpre- tations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily refl ect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other informa- tion shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concern- ing the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifi cally reserved. Rights and Permissions This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo. Under the Creative Commons Attribution license, you are free to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt this work, including for commercial purposes, under the following conditions: Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: World Bank. 2018. Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2018: Piecing Together the Poverty Puzzle. Washington, DC: World Bank. License: Creative Commons Attribu- tion CC BY 3.0 IGO Translations—If you create a translation of this work, please add the following disclaimer along with the attribution: This translation was not created by The World Bank and should not be considered an offi cial World Bank translation. -

Human Development Report 2016

Human Development Report 2016 Human Development for Everyone Empowered lives. Resilient nations. Human Development Report 2016 | Human Development for Everyone for Development Human | Report 2016 Development Human The 2016 Human Development Report is the latest in the series of global Human Development Reports published by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) since 1990 as independent, analytically and empirically grounded discussions of major development issues, trends and policies. Additional resources related to the 2016 Human Development Report can be found online at http://hdr.undp.org, including digital versions of the Report and translations of the overview in more than 20 languages, an interactive web version of the Report, a set of background papers and think pieces commissioned for the Report, interactive maps and databases of human development indicators, full explanations of the sources and methodologies used in the Report’s composite indices, country profiles and other background materials as well as previous global, regional and national Human Development Reports. The 2016 Report and the best of Human Development Report Office content, including publications, data, HDI rankings and related information can also be accessed on Apple iOS and Human Development AndroidReport smartphones2016 via a new and easy to use mobile app. Human Development for Everyone The cover reflects the basic message that human development is for everyone—in the human development journey no one can be left out. Using an abstract approach, the cover conveys three fundamental points. First, the upward moving waves in blue and whites represent the road ahead that humanity has to cover to ensure universal human development. -

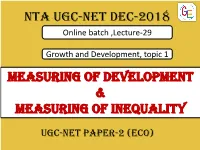

Measuring of Development & Measuring of Inequality Nta UGC

Nta UGC-NET dec-2018 Online batch ,Lecture-29 Growth and Development, topic 1 Measuring of development & Measuring of inequality UGC-NET PAPER-2 (ECO) Measuring of development 1.Measuring development 1.PQLI 3.Multy-dimensional HDI (1979) Poverty index(MPI) Replaced 2010 HPI 1997 2.HDI 4.Gender (1990) inequality Index. 1. Physical Quality Of Life Index (PQLI): In 1979, D. Morris constructed a composite Physical Quality of Life Index (PQLI). He therefore, combines three component indicators of Infant Mortality, Life Expectancy and Basic Literacy to measure performance in meeting the basic needs of the people. life expectancy is measured in terms of years, infant mortality rate in terms of per thousand and basic literacy rate in terms of percentage. the choice of indicators are: 1. Life 2. Infant 3. Literacy Expectancy Mortality Indicator (LI) Indicator Indicator (LEI) (IMI) For life exp. For IMI- For literacy rate. Upper limit – 77 years. Upper limit- 09 Upper limit – 100 Lower limit- 28 years. Lower - 229 Lower limit- 0 Short forms- L.I.L PQLI index is measured as- LEI+IMI+LI PQLI= 3 PQLI is published by UNDP. 2. Human Development Index (HDI): Considering quality of Life Index, the United Nations was the first to prepare and publish Human Development Index in the year 1990. HDI originally developed by Mahbub ul Huq He formed a group of developed economist including Paul Streeten , Frances Stewart, Gustav Ranis, Griffen, Sudhir Anand, Meghnad Desai, and Amartya Sen. A.K.Sen use his work in this own work on Human capabilities. HDI is based on Non-economics social indicators like education, literacy school , health, and services. -

Population and Poverty: a Review and Restatement

Population Council Knowledge Commons Poverty, Gender, and Youth Social and Behavioral Science Research (SBSR) 1997 Population and poverty: A review and restatement Geoffrey McNicoll Population Council Follow this and additional works at: https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/departments_sbsr-pgy Part of the Demography, Population, and Ecology Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, International Public Health Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation McNicoll, Geoffrey. 1997. "Population and poverty: A review and restatement," Policy Research Division Working Paper no. 105. New York: Population Council. This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Population Council. Population and Poverty: A Review and Restatement Geoffrey McNicoll 1997 No. 105 Population and Poverty: A Review and Restatement Geoffrey McNicoll Geoffrey McNicoll is Senior Associate, Policy Research Division, Population Council, New York, and Professor, Research School of Social Sciences, Austra- lian National University, Canberra. This paper was prepared under a grant from the United Nations Population Fund. Comments by Richard Leete and Cynthia Lloyd are acknowledged. Abstract Worldwide in the 1990s over one billion persons are estimated to have a purchasing power of below a dollar per day, the conventional de- marcation of “absolute poverty.” Other dimensions of poverty, extending beyond income measures to encompass a person’s broader capabilities and social functioning, are less empirically accessible. Poverty is commonly thought to be associated with high fertility and rapid population growth (regionally, South Asia and Africa have the highest poverty rates), but that view finds little support in the extensive statistical research literature on population and poverty.