Adapting Pride and Prejudice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hiff and Bafta New York to Honor Bevan and Fellner of Working Title Films With

THE HAMPTONS INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL IN PARTNERSHIP WITH THE BRITISH ACADEMY OF FILM AND TELEVISION ARTS, NEW YORK HONORS WORKING TITLE FILMS CO-CHAIRS - TIM BEVAN AND ERIC FELLNER WITH THE GOLDEN STARFISH AWARD FOR LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AS PART OF THE FESTIVAL’S “FOCUS ON UK FILM.” BAFTA and Academy® Award Winner Renée Zellweger Will Introduce the Honorees and be joined by Richard Curtis, Joe Wright and Edgar Wright to toast the Producers. East Hampton, NY (September 17, 2013) - The Hamptons International Film Festival (HIFF) and the British Academy of Film and Television Arts New York (BAFTA New York), announced today that they will present Tim Bevan and Eric Fellner, co-chairs of British production powerhouse Working Title Films, with this year’s Golden Starfish Award for Lifetime Achievement on October 12th during the festival. Actress, Renée Zellweger, who came to prominence as the star of Working Title Films’ Bridget Jones’ Diary movies, will introduce the event. Working Title Films has produced some of the most well known films from the UK including LES MISERABLES, ATONEMENT, FOUR WEDDINGS AND A FUNERAL, ELIZABETH, and BILLY ELLIOT to name just a few. Richard Curtis (ABOUT TIME, LOVE ACTUALLY), Edgar Wright (THE WORLD'S END, SHAUN OF THE DEAD) and Joe Wright (ANNA KARENINA, ATONEMENT), three directors and longtime collaborators responsible for some of Working Title Films most acclaimed titles, will join Renee Zellweger, Tim Bevan and Eric Fellner in conversation for an insider’s view of Working Title Films. “The Hamptons International Film Festival is pleased to recognize Working Title Films and its incredible body of work,” said Anne Chaisson, Executive Director of The Hamptons International Film Festival. -

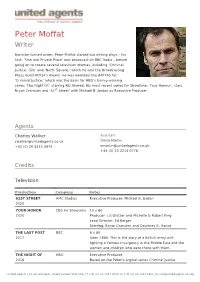

Peter Moffat Writer

Peter Moffat Writer Barrister turned writer, Peter Moffat started out writing plays – his first, ‘Fine and Private Place’ was broadcast on BBC Radio – before going on to create several television dramas, including ‘Criminal Justice, ‘Silk’ and ‘North Square,’ which he won the Broadcasting Press Guild Writer’s Award. He was awarded two BAFTAS for ‘Criminal Justice,’ which was the basis for HBO’s Emmy-winning series ‘The Night Of,’ starring Riz Ahmed. His most recent series for Showtime, ‘Your Honour,’ stars Bryan Cranston and ‘61st Street’ with Michael B. Jordan as Executive Producer. Agents Charles Walker Assistant [email protected] Olivia Martin +44 (0) 20 3214 0874 [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0778 Credits Television Production Company Notes 61ST STREET AMC Studios Executive Producer: Michael B. Jordan 2020 YOUR HONOR CBS for Showtime 10 x 60 2020 Producer: Liz Glotzer and Michelle & Robert King Lead Director: Ed Berger Starring: Bryan Cranston and Courtney B. Vance THE LAST POST BBC 6 x 60 2017 Aden 1965. This is the story of a British army unit fighting a Yemeni insurgency in the Middle East and the women and children who were there with them. THE NIGHT OF HBO Executive Producer 2016 Based on the Peter's orginal series Criminal Justice United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes UNDERCOVER BBC1 6 x60' with Sophie Okonedo and Adrian Lester, Denis 2015 Haysbert Director James Hawes, Exec Producer Peter Moffat THE VILLAGE series Company Pictures 6 x 60' with John Simm, Maxine Peake, Juliet Stevenson 1 / BBC1 Producer: Emma Burge; Director: Antonia Bird 2013 SILK 2 BBC1 6 x 60' With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Frances 2012 Barber, and Neil Stuke Producer: Richard Stokes; Directors: Alice Troughton, Jeremy Webb, Peter Hoar SILK BBC1 6 x 60' 2011 With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Natalie Dormer, Tom Hughes and Neil Stuke. -

Production Notes

A Film by John Madden Production Notes Synopsis Even the best secret agents carry a debt from a past mission. Rachel Singer must now face up to hers… Filmed on location in Tel Aviv, the U.K., and Budapest, the espionage thriller The Debt is directed by Academy Award nominee John Madden (Shakespeare in Love). The screenplay, by Matthew Vaughn & Jane Goldman and Peter Straughan, is adapted from the 2007 Israeli film Ha-Hov [The Debt]. At the 2011 Beaune International Thriller Film Festival, The Debt was honoured with the Special Police [Jury] Prize. The story begins in 1997, as shocking news reaches retired Mossad secret agents Rachel (played by Academy Award winner Helen Mirren) and Stephan (two-time Academy Award nominee Tom Wilkinson) about their former colleague David (Ciarán Hinds of the upcoming Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy). All three have been venerated for decades by Israel because of the secret mission that they embarked on for their country back in 1965-1966, when the trio (portrayed, respectively, by Jessica Chastain [The Tree of Life, The Help], Marton Csokas [The Lord of the Rings, Dream House], and Sam Worthington [Avatar, Clash of the Titans]) tracked down Nazi war criminal Dieter Vogel (Jesper Christensen of Casino Royale and Quantum of Solace), the feared Surgeon of Birkenau, in East Berlin. While Rachel found herself grappling with romantic feelings during the mission, the net around Vogel was tightened by using her as bait. At great risk, and at considerable personal cost, the team’s mission was accomplished – or was it? The suspense builds in and across two different time periods, with startling action and surprising revelations that compel Rachel to take matters into her own hands. -

Governing New Guinea New

Governing New Guinea New Guinea Governing An oral history of Papuan administrators, 1950-1990 Governing For the first time, indigenous Papuan administrators share their experiences in governing their country with an inter- national public. They were the brokers of development. After graduating from the School for Indigenous Administrators New Guinea (OSIBA) they served in the Dutch administration until 1962. The period 1962-1969 stands out as turbulent and dangerous, Leontine Visser (Ed) and has in many cases curbed professional careers. The politi- cal and administrative transformations under the Indonesian governance of Irian Jaya/Papua are then recounted, as they remained in active service until retirement in the early 1990s. The book brings together 17 oral histories of the everyday life of Papuan civil servants, including their relationship with superiors and colleagues, the murder of a Dutch administrator, how they translated ‘development’ to the Papuan people, the organisation of the first democratic institutions, and the actual political and economic conditions leading up to the so-called Act of Free Choice. Finally, they share their experiences in the UNTEA and Indonesian government organisation. Leontine Visser is Professor of Development Anthropology at Wageningen University. Her research focuses on governance and natural resources management in eastern Indonesia. Leontine Visser (Ed.) ISBN 978-90-6718-393-2 9 789067 183932 GOVERNING NEW GUINEA KONINKLIJK INSTITUUT VOOR TAAL-, LAND- EN VOLKENKUNDE GOVERNING NEW GUINEA An oral history of Papuan administrators, 1950-1990 EDITED BY LEONTINE VISSER KITLV Press Leiden 2012 Published by: KITLV Press Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies) P.O. -

Atonement (2007) Compiled by Jay Seller

Literature to Film, lecture on Atonement (2007) Compiled by Jay Seller Atonement (2007) Universal Pictures Director: Joe Wright Screenwriter: Christopher Hampton Novel: Ian McEwan 123 minutes Cast Cecilia Tallis Keira Knightley Robbie Turner James McAvoy Briony Tallis,Briony Romola Garai Older Briony Vanessa Redgrave Briony Taliis,Briony Saoirse Ronan Grace Turner Brenda Blethyn Singing Housemaid Allie MacKay Betty Julia Ann West Lola Quincey Juno Temple Jackson Quincey Charlie Von Simpson Leon Tallis Patrick Kennedy Paul Marshall Benedict Cumberbatch Emily Tallis Harriet Walter Fiona MacGuire Michelle Duncan Sister Drummond Gina McKee Police Constable Leander Deeny Luc Cornet Jeremie Renier Police Sergeant Peter McNeil O’Connor Tommy Nettle Daniel Mays Danny Hardman Alfie Allen Pierrot,Pierrot Jack Harcourt Frenchmen Michel Vuillemoz Jackson,Jackson Ben Harcourt Frenchmen Lionel Abelanski Frank Mace Nonso Anozie Naval Officer Tobias Menzies Crying Soldier Paul Stocker Police Inspector Peter Wright Solitary Sunbather Alex Noodle Vicar John Normington Mrs. Jarvis Wendy Nottingham Beach Soldier Roger Evans, Bronson Webb, Ian Bonar, Oliver Gilbert Interviewer Anthony Minghella Soldier in Bray Bar Jamie Beamish, Johnny Harris, Nick Bagnall, Billy Seymour, Neil Maskell Soldier With Ukulele Paul Harper Probationary Nurse Charlie Banks, Madeleine Crowe, Olivia Grant, Scarlett Dalton, Katy Lawrence, Jade Moulla, Georgia Oakley, Alice Orr-Ewing, Catherine Philps, Bryony Reiss, DSarah Shaul, Anna Singleton, Emily Thomson Hospital Admin Assistant Kelly Scott Soldier at Hospital Entrance Mark Holgate Registrar Ryan Kiggell Staff Nurse Vivienne Gibbs Second Soldier at Hospital Entrance Matthew Forest Injured Sergeant Richard Stacey Soldier Who Looks Like Robbie Jay Quinn Mother of Evacuees Tilly Vosburgh Evacuee Child Angel Witney, Bonnie Witney, Webb Bem 1 Primary source director’s commentary by Joe Wright. -

Ian Mcewan's Atonement

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI Pedagogická fakulta Katedra anglického jazyka ANETA VRÁGOVÁ III. ročník – prezenční studium Obor: Anglický jazyk se zaměřením na vzdělávání – Německý jazyk se zaměřením na vzdělávání IAN MCEWAN’S ATONEMENT: COMPARISON OF THE NOVEL AND THE FILM ADAPTATION Bakalářská práce Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Josef Nevařil, Ph.D. Olomouc 2015 Prohlášení: Prohlašuji, že jsem závěrečnou práci vypracovala samostatně a použila jen uvedených pramenů a literatury. V Olomouci (datum) ……………………………………………… vlastnoruční podpis I would like to thank Mgr. Josef Nevařil, Ph. D. for his assistance, comments and guidance throughout the writing process. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 6 1. BIOGRAPHY OF IAN MCEWAN ...................................................................... 7 1.1. BIOGRAPHY ................................................................................................... 7 1.2. LITERARY OUTPUT ...................................................................................... 8 1.3. AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL ASPECTS ................................................................ 9 2. POSTMODERNISM .......................................................................................... 12 3. COMPARISON OF THE NOVEL ATONEMENT AND THE FILM ADAPTATION ......................................................................................................................... 14 3.1. NOVEL: GENERAL INFORMATION ........................................................ -

The Art of Writing Proposals by Adam Przeworski and Frank Salomon

1988, 1995 The Art of Writing Proposals By Adam Przeworski and Frank Salomon Writing proposals for research funding is a peculiar facet of North American academic culture, and as with all things cultural, its attributes rise only partly into public consciousness. A proposal's overt function is to persuade a committee of scholars that the project shines with the three kinds of merit all disciplines value, namely, conceptual innovation, methodological rigor, and rich, substantive content. But to make these points stick, a proposal writer needs a feel for the unspoken customs, norms, and needs that govern the selection process itself. These are not really as arcane or ritualistic as one might suspect. For the most part, these customs arise from the committee's efforts to deal in good faith with its own problems: incomprehension among disciplines, work overload, and the problem of equitably judging proposals that reflect unlike social and academic circumstances. Writing for committee competition is an art quite different from research work itself. After long deliberation, a committee usually has to choose among proposals that all possess the three virtues mentioned above. Other things being equal, the proposal that is awarded funding is the one that gets its merits across more forcefully because it addresses these unspoken needs and norms as well as the overt rules. The purpose of these pages is to give competitors for Council fellowships and funding a more even start by making explicit some of those normally unspoken customs and needs. Capture -

Imagination and Thematic Reality in the African Novel: a New Vision for African Novelists

Advances in Literary Study, 2018, 6, 8-18 http://www.scirp.org/journal/als ISSN Online: 2327-4050 ISSN Print: 2327-4034 Imagination and Thematic Reality in the African Novel: A New Vision for African Novelists Abdoulaye Hakibou Language Department, University of Parakou, Parakou, Benin How to cite this paper: Hakibou, A. Abstract (2018). Imagination and Thematic Reality in the African Novel: A New Vision for The present study on the topic “Imagination and thematic reality in the Afri- African Novelists. Advances in Literary can novel: a new vision to African novelists” aims to show the limitation of Study, 6, 8-18. the contribution of the African literary works to the good governance and de- https://doi.org/10.4236/als.2018.61002 velopment process of African countries through the thematic choices and to Received: October 17, 2017 propose a new vision in relation to those thematic choices and to the structur- Accepted: December 18, 2017 al organisation of those literary works. The study is carried out through the Published: December 21, 2017 theory of narratology by Genette (1980) and the narrative study by Chatman Copyright © 2018 by author and (1978) as applied to the novels by Chinua Achebe, essentially on the notion of Scientific Research Publishing Inc. order by Genette and the elements of a narrative by Chatman. It is a thematic This work is licensed under the Creative and structural analysis that helps the researcher to be aware of the limitation Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0). of the contribution of African fiction to the good governance of African States http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ and their real development, for the reason that themes and the structural or- Open Access ganisation of those works are past-oriented. -

Serializing the Middle Ages: Television and the (Re)Production of Pop Culture Medievalisms

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2012 Serializing the Middle Ages: Television and the (Re)Production of Pop Culture Medievalisms Sara McClendon Knight Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Knight, Sara McClendon, "Serializing the Middle Ages: Television and the (Re)Production of Pop Culture Medievalisms" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 170. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/170 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SERIALIZING THE MIDDLE AGES: TELEVISION AND THE (RE)PRODUCTION OF POP CULTURE MEDIEVALISMS A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English The University of Mississippi by Sara McClendon Knight May 2012 Copyright Sara McClendon Knight 2012 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT In his now canonical “Dreaming the Middle Ages,” Umberto Eco famously quips that “it seems that people like the Middle Ages” (61). Eco’s apt sentiment still strikes a resonant chord some twenty years after its publication; there is indeed something about the Middle Ages that continues to fascinate our postmodern society. One of the most tangible ways this interest manifests itself is through our media. This project explores some of the ways that representations of the medieval past function within present-day reimaginings in the media. More specifically, television’s obvious visual textuality, widespread popularity, and virtually untapped scholarly potential offer an excellent medium through which to analyze pop culture medievalisms—the creative tensions that exists between medieval culture and the way it is reimagined, recreated, or reproduced in the present. -

A Companion to Literature, Film, and Adaptation Blackwell Companions to Literature and Culture

A Companion to Literature, Film, and Adaptation Blackwell Companions to Literature and Culture This series offers comprehensive, newly written surveys of key periods and movements and certain major authors, in English literary culture and history. Extensive volumes provide new perspectives and positions on contexts and on canonical and post-canonical texts, orientating the beginning student in new fields of study and providing the experienced undergraduate and new graduate with current and new directions, as pioneered and developed by leading scholars in the field. Published Recently 62. A Companion to T. S. Eliot Edited by David E. Chinitz 63. A Companion to Samuel Beckett Edited by S. E. Gontarski 64. A Companion to Twentieth-Century United States Fiction Edited by David Seed 65. A Companion to Tudor Literature Edited by Kent Cartwright 66. A Companion to Crime Fiction Edited by Charles Rzepka and Lee Horsley 67. A Companion to Medieval Poetry Edited by Corinne Saunders 68. A New Companion to English Renaissance Literature and Culture Edited by Michael Hattaway 69. A Companion to the American Short Story Edited by Alfred Bendixen and James Nagel 70. A Companion to American Literature and Culture Edited by Paul Lauter 71. A Companion to African American Literature Edited by Gene Jarrett 72. A Companion to Irish Literature Edited by Julia M. Wright 73. A Companion to Romantic Poetry Edited by Charles Mahoney 74. A Companion to the Literature and Culture of the American West Edited by Nicolas S. Witschi 75. A Companion to Sensation Fiction Edited by Pamela K. Gilbert 76. A Companion to Comparative Literature Edited by Ali Behdad and Dominic Thomas 77. -

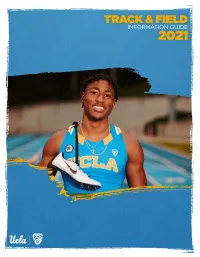

2020 21 Media Guide Comple

2021 UCLA TRACK & FIELD 2021 QUICK FACTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Location Los Angeles, CA The 2021 Bruins Men’s All-Time Indoor Top 10 65-66 Rosters 2-3 Athletic Dept. Address 325 Westwood Plaza Women’s All-Time Indoor Top 10 67-68 Coaching Staff 4-9 Los Angeles, CA 90095 Men’s All-Time Outdoor Top 10 69-71 Men’s Athlete Profles 10-26 Athletics Phone (310) 825-8699 Women’s All-Time Outdoor Top 10 72-74 Women’s Athlete Profles 27-51 Ticket Offce (310) UCLA-WIN Drake Stadium 75 Track & Field Offce Phone (310) 794-6443 History/Records Drake Stadium Records 76 Chancellor Dr. Gene Block UCLA-USC Dual Meet History 52 Bruins in the Olympics 77-78 Director of Athletics Martin Jarmond Pac-12 Conference History 53-55 USA Track & Field Hall of Fame Bruins 79-81 Associate Athletic Director Gavin Crew NCAA Championships All-Time Results 56 Sr. Women’s Administrator Dr. Christina Rivera NCAA Men’s Champions 57 Faculty Athletic Rep. Dr. Michael Teitell NCAA Women’s Champions 58 Home Track (Capacity) Drake Stadium (11,700) Men’s NCAA Championship History 59-61 Enrollment 44,742 Women’s NCAA Championship History 62-63 NCAA Indoor All-Americans 64 Founded 1919 Colors Blue and Gold Nickname Bruins Conference Pac-12 National Affliation NCAA Division I Director of Track & Field/XC Avery Anderson Record at UCLA (Years) Fourth Year Asst. Coach (Jumps, Hurdles, Pole Vault) Marshall Ackley Asst. Coach (Sprints, Relays) Curtis Allen Asst. Coach (Distance) Devin Elizondo Asst. Coach (Distance) Austin O’Neil Asst. -