Books and Letters in Joe Wright's Pride & Prejudice (2005)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hiff and Bafta New York to Honor Bevan and Fellner of Working Title Films With

THE HAMPTONS INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL IN PARTNERSHIP WITH THE BRITISH ACADEMY OF FILM AND TELEVISION ARTS, NEW YORK HONORS WORKING TITLE FILMS CO-CHAIRS - TIM BEVAN AND ERIC FELLNER WITH THE GOLDEN STARFISH AWARD FOR LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AS PART OF THE FESTIVAL’S “FOCUS ON UK FILM.” BAFTA and Academy® Award Winner Renée Zellweger Will Introduce the Honorees and be joined by Richard Curtis, Joe Wright and Edgar Wright to toast the Producers. East Hampton, NY (September 17, 2013) - The Hamptons International Film Festival (HIFF) and the British Academy of Film and Television Arts New York (BAFTA New York), announced today that they will present Tim Bevan and Eric Fellner, co-chairs of British production powerhouse Working Title Films, with this year’s Golden Starfish Award for Lifetime Achievement on October 12th during the festival. Actress, Renée Zellweger, who came to prominence as the star of Working Title Films’ Bridget Jones’ Diary movies, will introduce the event. Working Title Films has produced some of the most well known films from the UK including LES MISERABLES, ATONEMENT, FOUR WEDDINGS AND A FUNERAL, ELIZABETH, and BILLY ELLIOT to name just a few. Richard Curtis (ABOUT TIME, LOVE ACTUALLY), Edgar Wright (THE WORLD'S END, SHAUN OF THE DEAD) and Joe Wright (ANNA KARENINA, ATONEMENT), three directors and longtime collaborators responsible for some of Working Title Films most acclaimed titles, will join Renee Zellweger, Tim Bevan and Eric Fellner in conversation for an insider’s view of Working Title Films. “The Hamptons International Film Festival is pleased to recognize Working Title Films and its incredible body of work,” said Anne Chaisson, Executive Director of The Hamptons International Film Festival. -

Ludacris – Red Light District Brothers in Arms the Pacifier

Pickwick's Video/DVD Rentals – New Arrivals 19. Sept. 2005 Marc Aurel Str. 10-12, 1010 Vienna Tel. 01-533 0182 – open daily – http://www.pickwicks.at/ __________________________________________________________________ Ludacris – Red Light District Genre: Music Synopsis: Live concert from Amsterdam plus three music videos. Brothers In Arms Genre: Action Actors: David Carradine, Kenya Moore, Gabriel Casseus, Antwon Tanner, Raymond Cruz Director: Jean-Claude La Marre Synopsis: A crew of outlaws set out to rob the town boss who murdered one of their kinsmen. Driscoll is warned so his thugs surround the outlaws and soon there is a shootout. Set in the American West. The Pacifier Genre: Comedy Actors: Vin Diesel, Lauren Graham, Faith Ford, Brittany Snow, Max Theriot, Carol Kane, Brad Gardett Director: Adam Shankman Synopsis: The story of an undercover agent who, after failing to protect an important government scientist, learns the man's family is in danger. In an effort to redeem himself, he agrees to take care of the man's children only to discover that child care is his toughest mission yet. Pickwick's Video/DVD Rentals – New Arrivals 19. Sept. 2005 Marc Aurel Str. 10-12, 1010 Vienna Tel. 01-533 0182 – open daily – http://www.pickwicks.at/ __________________________________________________________________ The Killer Language: Japanese Genre: Action Actors: Chow Yun Fat Director: John Woo Synopsis: The story of an assassin, Jeffrey Chow (aka Mickey Mouse) who takes one last job so he can retire and care for his girlfriend Jenny. When his employers betray him, he reluctantly joins forces with Inspector Lee (aka Dumbo), the cop who is pursuing him. -

The 48 Stars That People Like Less Than Anne Hathaway by Nate Jones

The 48 Stars That People Like Less Than Anne Hathaway By Nate Jones Spend a few minutes reading blog comments, and you might assume that Anne Hathaway’s approval rating falls somewhere between that of Boko Haram and paper cuts — but you'd actually be completely wrong. According to E-Poll likability data we factored into Vulture's Most Valuable Stars list, the braying hordes of Hathaway haters are merely a very vocal minority. The numbers say that most people actually like her. Even more shocking? Who they like her more than. In calculating their E-Score Celebrity rankings, E-Poll asked people how much they like a particular celebrity on a six-point scale, which ranged from "like a lot" to "dislike a lot." The resulting Likability percentage is the number of respondents who indicated they either "like" Anne Hathaway or "like Anne Hathaway a lot." Hathaway's 2014 Likability percentage was 67 percent — up from 66 percent in 2013 — which doesn't quite make her Will Smith (85 percent), Sandra Bullock (83 percent), Jennifer Lawrence (76 percent), or even Liam Neeson (79 percent), but it does put her well above plenty of stars whose appeal has never been so furiously impugned on Twitter. Why? Well, why not? Anne Hathaway is a talented actress and seemingly a nice person. The objections to her boiled down to two main points: She tries too hard, and she's overexposed. But she's been absent from the screen since 2012'sLes Misérables, so it's hard to call her overexposed now. And trying too hard isn't the worst thing in the world, especially when you consider the alternative. -

A Dangerous Method

A David Cronenberg Film A DANGEROUS METHOD Starring Keira Knightley Viggo Mortensen Michael Fassbender Sarah Gadon and Vincent Cassel Directed by David Cronenberg Screenplay by Christopher Hampton Based on the stage play “The Talking Cure” by Christopher Hampton Based on the book “A Most Dangerous Method” by John Kerr Official Selection 2011 Venice Film Festival 2011 Toronto International Film Festival, Gala Presentation 2011 New York Film Festival, Gala Presentation www.adangerousmethodfilm.com 99min | Rated R | Release Date (NY & LA): 11/23/11 East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Donna Daniels PR Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Donna Daniels Ziggy Kozlowski Carmelo Pirrone 77 Park Ave, #12A Jennifer Malone Lindsay Macik New York, NY 10016 Rebecca Fisher 550 Madison Ave 347-254-7054, ext 101 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 New York, NY 10022 Los Angeles, CA 90036 212-833-8833 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8844 fax 323-634-7030 fax A DANGEROUS METHOD Directed by David Cronenberg Produced by Jeremy Thomas Co-Produced by Marco Mehlitz Martin Katz Screenplay by Christopher Hampton Based on the stage play “The Talking Cure” by Christopher Hampton Based on the book “A Most Dangerous Method” by John Kerr Executive Producers Thomas Sterchi Matthias Zimmermann Karl Spoerri Stephan Mallmann Peter Watson Associate Producer Richard Mansell Tiana Alexandra-Silliphant Director of Photography Peter Suschitzky, ASC Edited by Ronald Sanders, CCE, ACE Production Designer James McAteer Costume Designer Denise Cronenberg Music Composed and Adapted by Howard Shore Supervising Sound Editors Wayne Griffin Michael O’Farrell Casting by Deirdre Bowen 2 CAST Sabina Spielrein Keira Knightley Sigmund Freud Viggo Mortensen Carl Jung Michael Fassbender Otto Gross Vincent Cassel Emma Jung Sarah Gadon Professor Eugen Bleuler André M. -

Nikωletta Skarlatos Make up Designer / Make up Department Head Journeyman Makeup Artist Film & Television

NIKΩLETTA SKARLATOS MAKE UP DESIGNER / MAKE UP DEPARTMENT HEAD JOURNEYMAN MAKEUP ARTIST FILM & TELEVISION FUTURE MAN (Pilot, Seasons 1 and 2) (Make-up Department Head, Make-up Designer) Director: Seth Rogan & Evan Goldberg Production Company: Point Grey Pictures Cast: Josh Hutcherson, Eliza Coupe, Derek Wilson, Glenne Headley, Ed Begley Jr. NAPPILY EVER AFTER (Make-up Department Head, Make-up Designer) Personal: Sanaa Lathan & Lynne Whitfield, Director: Haifaa Al-Mansour Production Company: Netflix Cast: Sanaa Lathan, Lynne Whitfield, Ricky Whittle, Lyriq Bent, Ernie Hudson FREE STATE OF JONES (Make-up Department Head, Makeup Designer) Director: Gary Ross Production Company: Bluegrass Films Cast: Matthew McConaughey, Keri Russell, Mahershala Ali, Gugu Mbatha-Raw THE HUNGER GAMES: MOCKINGJAY PART 2 (Make-up Department Head) Director: Francis Lawrence Production Company: Lionsgate Cast: Jennifer Lawrence, Mahershala Ali, Liam Hemsworth, Josh Hutcherson, Elizabeth Banks, Woody Harrelson, Phillip Seymour Hoffmann, Donald Sutherland THE PERFECT GUY (Make-up Department Head, Make-up Designer) Director: David Rosenthal Production Company: Screen Gems Cast: Sanaa Lathan, Michael Ealy, Morris Chestnut, Charles Dutton LUX ARTISTS | 1 THE HUNGER GAMES: MOCKINGJAY PART 1 (Make-up Department Head) Director: Francis Lawrence Production Company: Lionsgate Cast: Jennifer Lawrence. Personal: Liam Hemsworth, Josh Hutcherson, Elizabeth Banks, Woody Harrelson, Mahershala Ali Nominated, Best Period and/or Character Make-up, Make-up and Hair Guild Awards (2015) SOLACE (Makeup Department Head, Makeup Designer) Director: Afonso Poyart Production Company: Eden Rock Media Cast: Anthony Hopkins, Colin Farrell, Abbie Cornish, Jeffrey Dean Morgan THE HUNGER GAMES: CATCHING FIRE (Key Make-up Artist) Director: Francis Lawrence Production Company: Lionsgate Cast: Jennifer Lawrence. -

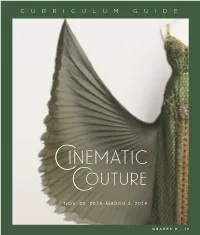

C U R R I C U L U M G U I

C U R R I C U L U M G U I D E NOV. 20, 2018–MARCH 3, 2019 GRADES 9 – 12 Inside cover: From left to right: Jenny Beavan design for Drew Barrymore in Ever After, 1998; Costume design by Jenny Beavan for Anjelica Huston in Ever After, 1998. See pages 14–15 for image credits. ABOUT THE EXHIBITION SCAD FASH Museum of Fashion + Film presents Cinematic The garments in this exhibition come from the more than Couture, an exhibition focusing on the art of costume 100,000 costumes and accessories created by the British design through the lens of movies and popular culture. costumer Cosprop. Founded in 1965 by award-winning More than 50 costumes created by the world-renowned costume designer John Bright, the company specializes London firm Cosprop deliver an intimate look at garments in costumes for film, television and theater, and employs a and millinery that set the scene, provide personality to staff of 40 experts in designing, tailoring, cutting, fitting, characters and establish authenticity in period pictures. millinery, jewelry-making and repair, dyeing and printing. Cosprop maintains an extensive library of original garments The films represented in the exhibition depict five centuries used as source material, ensuring that all productions are of history, drama, comedy and adventure through period historically accurate. costumes worn by stars such as Meryl Streep, Colin Firth, Drew Barrymore, Keira Knightley, Nicole Kidman and Kate Since 1987, when the Academy Award for Best Costume Winslet. Cinematic Couture showcases costumes from 24 Design was awarded to Bright and fellow costume designer acclaimed motion pictures, including Academy Award winners Jenny Beavan for A Room with a View, the company has and nominees Titanic, Sense and Sensibility, Out of Africa, The supplied costumes for 61 nominated films. -

Press-Release-The-Endings.Pdf

Publication Date: September 4, 2018 Media Contact: Diane Levinson, Publicity [email protected] 212.354.8840 x248 The Endings Photographic Stories of Love, Loss, Heartbreak, and Beginning Again By Caitlin Cronenberg and Jessica Ennis • Foreword by Mary Harron 11 x 8 in, 136pp, Hardcover, Photographs throughout ISBN 978‐1‐4521‐5568‐5, $29.95 Featuring some of today’s most celebrated actresses, including Julianne Moore, Alison Pill, and Imogen Poots, the photographic vignettes in The Endings capture female characters in the throes of emotional transformation. Photographer Caitlin Cronenberg and art director Jessica Ennis created stories of heartbreak, relationship endings, and new beginnings—fictional but often inspired by real life—and set out to convey the raw emotions that are exposed in these most vulnerable states. Cronenberg and Ennis collaborated with each actress to develop a character, build the world she inhabits, and then photograph her as she lived the role before the camera. Patricia Clarkson depicts a woman meeting her younger lover in the campus library—even though they both know the relationship has been over since before it even began. Juno Temple portrays a broken‐hearted woman who engages in reckless and self‐destructive behavior to numb the sadness she feels. Keira Knightley ritualistically cleanses herself and her home after the death of her great love. Also featured are Jennifer Jason Leigh, Danielle Brooks, Tessa Thompson, Noomi Rapace, and many more. These intimate images combine the lush beauty and rich details of fashion photographs with the drama and narrative energy of film stills. Telling stories of sadness, loneliness, anger, relief, rebirth, freedom, and happiness, they are about relationship endings, but they are also about beginnings. -

The Hollywood Reporter November 2015

Reese Witherspoon (right) with makeup artist Molly R. Stern Photographed by Miller Mobley on Nov. 5 at Studio 1342 in Los Angeles “ A few years ago, I was like, ‘I don’t like these lines on my face,’ and Molly goes, ‘Um, those are smile lines. Don’t feel bad about that,’ ” says Witherspoon. “She makes me feel better about how I look and how I’m changing and makes me feel like aging is beautiful.” Styling by Carol McColgin On Witherspoon: Dries Van Noten top. On Stern: m.r.s. top. Beauty in the eye of the beholder? No, today, beauty is in the eye of the Internet. This, 2015, was the year that beauty went fully social, when A-listers valued their looks according to their “likes” and one Instagram post could connect with millions of followers. Case in point: the Ali MacGraw-esque look created for Kendall Jenner (THR beauty moment No. 9) by hairstylist Jen Atkin. Jenner, 20, landed an Estee Lauder con- tract based partly on her social-media popularity (40.9 million followers on Instagram, 13.3 million on Twitter) as brands slavishly chase the Snapchat generation. Other social-media slam- dunks? Lupita Nyong’o’s fluffy donut bun at the Cannes Film Festival by hairstylist Vernon Francois (No. 2) garnered its own hashtag (“They're calling it a #fronut,” the actress said on Instagram. “I like that”); THR cover star Taraji P. Henson’s diva dyna- mism on Fox’s Empire (No. 1) spawns thousands of YouTube tutorials on how to look like Cookie Lyon; and Cara Delevingne’s 22.2 million Instagram followers just might have something do with high-end brow products flying off the shelves. -

Atonement (2007) Compiled by Jay Seller

Literature to Film, lecture on Atonement (2007) Compiled by Jay Seller Atonement (2007) Universal Pictures Director: Joe Wright Screenwriter: Christopher Hampton Novel: Ian McEwan 123 minutes Cast Cecilia Tallis Keira Knightley Robbie Turner James McAvoy Briony Tallis,Briony Romola Garai Older Briony Vanessa Redgrave Briony Taliis,Briony Saoirse Ronan Grace Turner Brenda Blethyn Singing Housemaid Allie MacKay Betty Julia Ann West Lola Quincey Juno Temple Jackson Quincey Charlie Von Simpson Leon Tallis Patrick Kennedy Paul Marshall Benedict Cumberbatch Emily Tallis Harriet Walter Fiona MacGuire Michelle Duncan Sister Drummond Gina McKee Police Constable Leander Deeny Luc Cornet Jeremie Renier Police Sergeant Peter McNeil O’Connor Tommy Nettle Daniel Mays Danny Hardman Alfie Allen Pierrot,Pierrot Jack Harcourt Frenchmen Michel Vuillemoz Jackson,Jackson Ben Harcourt Frenchmen Lionel Abelanski Frank Mace Nonso Anozie Naval Officer Tobias Menzies Crying Soldier Paul Stocker Police Inspector Peter Wright Solitary Sunbather Alex Noodle Vicar John Normington Mrs. Jarvis Wendy Nottingham Beach Soldier Roger Evans, Bronson Webb, Ian Bonar, Oliver Gilbert Interviewer Anthony Minghella Soldier in Bray Bar Jamie Beamish, Johnny Harris, Nick Bagnall, Billy Seymour, Neil Maskell Soldier With Ukulele Paul Harper Probationary Nurse Charlie Banks, Madeleine Crowe, Olivia Grant, Scarlett Dalton, Katy Lawrence, Jade Moulla, Georgia Oakley, Alice Orr-Ewing, Catherine Philps, Bryony Reiss, DSarah Shaul, Anna Singleton, Emily Thomson Hospital Admin Assistant Kelly Scott Soldier at Hospital Entrance Mark Holgate Registrar Ryan Kiggell Staff Nurse Vivienne Gibbs Second Soldier at Hospital Entrance Matthew Forest Injured Sergeant Richard Stacey Soldier Who Looks Like Robbie Jay Quinn Mother of Evacuees Tilly Vosburgh Evacuee Child Angel Witney, Bonnie Witney, Webb Bem 1 Primary source director’s commentary by Joe Wright. -

Ian Mcewan's Atonement

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI Pedagogická fakulta Katedra anglického jazyka ANETA VRÁGOVÁ III. ročník – prezenční studium Obor: Anglický jazyk se zaměřením na vzdělávání – Německý jazyk se zaměřením na vzdělávání IAN MCEWAN’S ATONEMENT: COMPARISON OF THE NOVEL AND THE FILM ADAPTATION Bakalářská práce Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Josef Nevařil, Ph.D. Olomouc 2015 Prohlášení: Prohlašuji, že jsem závěrečnou práci vypracovala samostatně a použila jen uvedených pramenů a literatury. V Olomouci (datum) ……………………………………………… vlastnoruční podpis I would like to thank Mgr. Josef Nevařil, Ph. D. for his assistance, comments and guidance throughout the writing process. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 6 1. BIOGRAPHY OF IAN MCEWAN ...................................................................... 7 1.1. BIOGRAPHY ................................................................................................... 7 1.2. LITERARY OUTPUT ...................................................................................... 8 1.3. AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL ASPECTS ................................................................ 9 2. POSTMODERNISM .......................................................................................... 12 3. COMPARISON OF THE NOVEL ATONEMENT AND THE FILM ADAPTATION ......................................................................................................................... 14 3.1. NOVEL: GENERAL INFORMATION ........................................................ -

29 Jan Litflix Week3

When? Where? What? Why? Pride and Prejudice Adapted from Jane Austen’s novel of the Saturday 30th 5Select January Elizabeth Bennet is one of five sisters whose mother is determined to find them same name. This tale of life in Regency 12.30pm suitable husbands. The arrival of a wealthy gentleman and his friends at a Great Britain is one of the most loved nearby mansion leads to an introduction between Elizabeth and the aloof Mr books and its numerous adaptations Darcy, to whom she takes an instant dislike. However, an unexpected attraction mean that a mass audience know the eventually develops. Starring Keira Knightley, Matthew Macfadyen and Judi famous characters and themes! Dench. Age rating: U Saturday 30th 5Star Stand By Me Based on Stephen King’s novella ‘The January Four 12-year-old best friends embark on a life-changing adventure in the Oregon Body’. King himself said the adaptation 4.55pm wilderness in search of a missing teenager's body, unaware of the trials and was ‘the best film ever made out of triumphs that await them. The film was nominated for an Academy Award for Best anything I've written.’ Adapted Screenplay. Age rating: 15 Saturday 30th Film4 Snow White and the Huntsman Based on the German fairytale ‘Snow January An evil queen learns that her reign will last forever if she kills a princess, so sends White’ compiled by the Brothers Grimm. 6.55pm a renowned warrior to find and murder her. However, he comes to realise his mistress's evil ways, and instead trains his intended victim to fight so they can bring the tyrant's rule to an end. -

Press Release

Press Release Stephanie Yera, 212-556-1957, [email protected] Contact: Angela He, 212-556-7850, [email protected] This press release can be downloaded from www.NYTCo.com. The New York Times’s TimesTalks Announces Collaboration with The Toronto International Film Festival for the 2015 Season First TimesTalks+TIFF in L.A. with Stars of “The Imitation Game” NEW YORK, February 11, 2015 – TimesTalks, The New York Times’s live, online and video conversations between Times journalists and today’s leading talents and thinkers, will collaborate with The Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) for the 2015 season. The first TimesTalks+TIFF will take place in Los Angeles on Monday, February 16, at 8 p.m. P.T., at the Paley Center for Media in Beverly Hills, CA, with a special interview with the stars of “The Imitation Game,” Benedict Cumberbatch and Keira Knightley. A live audience of film lovers in L.A., and audiences around the globe via live webcast, will watch these Academy Award nominees for Best Actor and Best Supporting Actress in conversation with Cara Buckley, New York Times Culture reporter and lead writer for The Carpetbagger, The Times’s awards season blog. “The Imitation Game,” winner of the prestigious Grolsch People’s Choice Award at the 2014 Toronto International Film Festival, is also nominated for Academy Awards for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Original Score, Best Film Editing and Best Production Design. This TimesTalks+TIFF is the launch event of the 2015 series of high-profile talks and panel discussions about the top films and performers of the year for consumer audiences in the key markets of New York, Toronto, London and Los Angeles.