Economic Backwardness of Uttar Dinajpur : a Block Level Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Committee on the Establishment of Educational Institutions for Educationally Backward Minorities

Government of India Ministry of Minority Affairs Committee on the Establishment of Educational Institutions for Educationally Backward Minorities Report M A E F Maulana Azad Education Foundation Maulana Azad Campus, Chelmsford Road, New Delhi - 110055 M A E F ii M A E F Contents Ch. Page Particulars No. No. Foreword 1 Acknowledgement 7 Preamble 9 1. Educational Status of Minorities 14 1.1 Literacy 15 1.1.1 Literacy Rate of Minorities 15 1.1.2 Minorities at Primary school Level Education 17 1.1.3 Minorities at Middle school Level Education 17 1.1.4 Minorities at Secondary Level (Matric) Education 18 1.1.5 Minorities at Higher Secondary (10+2) Level 19 1.1.6 Minorities at Graduate Level 21 1.2 Accessibility 23 1.2.1 Enrollment 24 1.2.2 Dropout 27 2. Demography of Minority Communities 30 2.1 Minority Dominant States (MDSs) 30 2.2 Minority Concentrated States (MCSs) 31 2.3 Minority Dominant Districts (MDDs) 33 2.4 Minority Concentrated Districts (MCDs) 35 2.5 Minority Dominant Cities (MDCs) 39 2.6 Minority Concentrated Cities (MCCs) 39 3. Recommendations 42 3.1 Central Schools 42 3.1.1 Recommendation 46 iii M A E F Ch. Page Particulars No. No. 3.2 Community Colleges 59 3.2.1 Governance 60 3.2.2 Programs and Curricula 61 3.2.3 Infrastructure and Faculty 66 3.2.4 Recommendation 66 3.3 National Institutes 69 3.3.1 National Institute of Science & Technology (NISTECH) 71 3.3.2 National Institute of Health and Allied Sciences (NIHAS) 80 3.3.3 National Institute of Architecture, Planning & Design (NIAPD) 86 3.3.4 National Institute of Climate Change and Disaster Management (NICCDM) 96 3.3.5 National Institute of Renewable Energy and Food Security (NIREFS) 104 3.3.6 Recommendation 129 4. -

Kala Azar Outbreak in West Bengal

Kala Azar Outbreak in West Bengal - Prabir Chatterjee, Md Kabiul Akhter Ali, Neel Kamal and Ajay Chakraborty 1 History Kala azar (visceral leishmaniasis) has not been common in West Bengal after the 1960s. Historically it was highly prevalent in the late 19 th century and early 20 th century. Satyajit Ray's father died of Kala Azar. U.N. Brahmachari was credited with preparing Urea Stibamine and treating many patients in Kolkata. Recent Trends Kala azar has increased from 1238 cases in West Bengal in 2001 to 3015 cases in 2004 and from 756 kala azar cases in 2009 to 1962 cases in 2011. Cases decreased in Murshidabad from 810 in 2005 to 288 in 2011, while they increased in neighbouring Malda from 268 in 2009 to 827 in 2011. In 2011 there was a spurt in cases in Darjeeling and close by areas of Uttar Dinajpur in North Bengal. U Dinajpur reported just 58 cases in 2010 but 180 cases in 2011. The Outbreak in Uttar Dinajpur Six blocks of Uttar Dinajpur were considered endemic for Kala azar. Cases were highest in Karandighi and Dalua blocks. While the number of cases was almost the same every year from 2008 to 2012 in five blocks- one block- Dalua (Chopra) suddenly detected a large number of cases in 2011. 1Respectively Medical Officer, Kaliaganj Municipality, Uttar Dinajpur, West Bengal; NVBDCP Consultant, Uttar Dinajpur; District Epidemiologist, Uttar Dinajpur; and Deputy II Chief Medical Officer of Health, Uttar Dinajpur. Email contact: [email protected] Locality One area called Bohura Line in Debijhora Tea Garden (Majhiali Panchayat) had 30 patients. -

An Analysis of Spatial Patterns of Disabled Persons in West Bengal

IJDS 2017; Vol. 04 No. 02, December 2017, pp. 137-145 137 ISSN: 2355 – 2158 DOI: An Analysis of Spatial Patterns of Disabled Persons in West Bengal *Md Monirul Islam *Senior Research Fellow, Dept. of Geography, Aliah University, Kolkata Abstract In this paper an attempt has been made to observe the spatial patterns of disabled persons by sex and residence in and across the districts of West Bengal. The research paper is exclusively based on secondary sources of data which have been taken from Census of India publications, New Delhi. Advanced statistical techniques have been used to analyze the data. Apart from, advanced cartographic techniques and GIS-MapInfo has also been used to visual representation of the data. The study reveals that disabled persons are highly concentrated in southern part of the state while, central part and a little area of northern part have the lower concentration. There is an enormous regional variation in the distributional patterns of male-female and rural- urban areas of the state. The study also examined the probable association between disability and selected socio- economic variables and it is observed that several variables are significantly associated with disability. Keywords: correlation, disabled persons, pattern, spatial. 1. Introduction According to Census of India 2011, there Persons with disabilities are the most are more than 26 millions disabled persons in oppressed, demoralized, marginalized, excluded India which implies every 22 persons are disabled section of the society. The concentration of out of 1000 among them 24 are male, while 20 disabled persons varies from place to place and are female and there are notable differentials in time to time (Islam et al., 2016). -

West Bengal Minorities' Development and Finance Corporation

West Bengal Minorities' Development & Finance Corporation • (A Statutory Corporation of Govt. of West Bengal) Memo No: 194 -MDC/VT-13-14 Date: 12th January,2021 ~: WBMDFC-.$1~ '5ll\JMt~. fly,: rn:f¥« C~IO:BI WEIT !-til~N,\S / <Pl©C.§iM~ - National Institute of Fashion Teechnology (NIFT). Kolkata C1J ~ ~~ WBMDFC ~ "'-!rnf@'-!> NIFT Kolkata-el ~ ~ QaR~ C~~ ~ "'-!IC<PFI ;qsrnc~··( ~ ~ri ')~M '9!11Jll~1, ~o~') - ~~M '9!11Jll'ffi, ~o~') ~ )O.oo C~ ~.oo ~'i:f ~~ ~1'1i:lR:,@-~ ~ ~'3m'i:f ~ "'-1-!Ci:ll~ ~ ~ I ~1'1i::1R,© .El'?l'~<J' .El<f~ ~ i6ll--ll~ ~ WBMDFC website (www.wbmdfc.org) 01~1 ~~~~1.,Ji:lR:,@~~~C<PR~TA&DA~~~~ I ~1.S1i:1f;©::4J'i:f~Rtii?l~~~'3 ~<Pf~~~~) "'-!HC\!>~g 1. ~ (17'/')o/')~) ~ s:i1fGf¥c;qs'G ~9RT'i:l" ~"'-l"i~l~ s:i1fGr¥c¥G "'-11..:ic<:1..:i) 2. ISrJJ s:i1fGf¥c;qs'G 3. ~ ~ f% ffi / '5JTl:ffif ffi 4. ~ <Pf9f 9ff51t9ffi, ~ ~ 5. "'-!r.!i.91~"'1-~ ~~~-~'i:f~GITT% ~ ~ ;::;,r-=ror--·,o I. ''II / 111. "I I / I -, '\ ····· o WEST BENGAL MINORITIES DEVELOPMENT & ~-~-~ - (7003597117) FINANCE CORPORATION (WBMDFC) "AMBER"DD- (NIFT) 27 /e, SECTOR 1, SALT LAKE CITY, KOLKATA 700 '1fibll<:15'/ '51"~~~'3 ~R~ 064 (WBMDFC) -18001202130 West Bengal Minorities' Development & Finance Corporation • (A Statutory Corporation of Govt. of West Bengal) 1 Memo no: 194-MDC/VT-13-14 Date: 12 h January, 2021 Notice Subject: Counselling/ Interview for Skill Training at National Institute of Fashion Technology (NIFT). Kolkata sponsored by WBMDFC Candidates applied for Skill Training course at National Institute of Fashion Technology (NIFT), Kolkata , sponsored by WBMDFC are hereby requested to attend Interview for selection from 19th January, 2021 to 22nd January, 2021 from 10.00 am to 2.p.m. -

Polytechnic College on P-1 Days I.E. 28-04-2021 I.C.W. GEWBLA-2021 for 8Th Phase

Route Chart for Movement of Polling Personnel from different pickup points to DC &RC Malda College & Malda Polytechnic College on P-1 days i.e. 28-04-2021 i.c.w. GEWBLA-2021 for 8th Phase Sl Route Sl Route No ( DC&RC Malda College ) No ( DC&RC Malda Polytechnic) 1 Kushida Bus Stand to Malda College Via Manikchak 1 Kushida Bus Stand to Malda Polytechnic College Via Manikchak Harishchandrapur Trekker Stand to to Malda Polytechnic College Manikchak 2 Harishchandrapur Trekker Stand to to Malda College Via Manikchak 2 Via Manikchak Bhaluka Bus Stand to to Malda Polytechnic College Via Laskarpur Kumarganj, 3 Bhaluka Bus Stand to to Malda College Via Laskarpur Kumarganj, Paranpur 3 Paranpur 4 Ratua Bus Stand to to Malda College Via Pukuria More, Sovanagar 4 Ratua Bus Stand to to Malda Polytechnic College Via Pukuria More, Sovanagar 5 Samsi Bus Stand to Malda College Via Alal, Gazole 5 Samsi Bus Stand to Malda Polytechnic College Via Alal, Gazole 6 Manikchak Bus Stand to Malda College Via Sovanagar, Milky 6 Manikchak Bus Stand to Malda Polytechnic College Via Sovanagar, Milky 7 Gazole Bus Stand to Malda College via Narayanpur 7 Gazole Bus Stand to Malda Polytechnic College via Narayanpur 8 Pakuahat Bus Stand to Malda College via Aiho 8 Pakuahat Bus Stand to Malda Polytechnic College via Aiho 9 Bulbulchandi More to Malda College Via Aiho, Mangalbari 9 Bulbulchandi More to Malda Polytechnic College Via Aiho, Mangalbari Seshroad Bus Stand to Malda College Via Baishnabnagar, 16 Mile, Seshroad Bus Stand to Malda Polytechnic College Via Baishnabnagar, -

Syllabus for B.A./B.Sc

UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL SYLLABUS FOR B.A./B.SC. HONOURS PROGRAMME COURSE IN ECONOMICS & B.A. PROGRAMME COURSE IN ECONOMICS UNDER CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM (CBCS) [Effective from 2018-2019] Department of Economics University of North Bengal Raja Rammohunpur, Darjeeling–734013, West Bengal, India CONTENTS Page No. 1. Syllabus for B.A./B.Sc. Honours Programme Course in Economics 04 2. Detailed Course Structure in Honours Programme Course 05 3. Scheme for Honours Programme Course in Economics 06 4. Skill Enhancement Course (SEC) 07 5. Discipline Specific Elective (DSE) 07 6. Credit Details Honours Programme Course in Economics 08 7. DSC101 – Introductory Microeconomics 09 8. DSC102 – Mathematical Methods for Economics-I 10 9. DSC203 – Introductory Macroeconomics 12 10. DSC204 – Mathematical Methods for Economics-II 13 11. DSC305 – Intermediate Microeconomics-I 14 12. DSC306 – Intermediate Macroeconomics-I 15 13. DSC307 – Statistical Methods for Economics-I 16 14. SEC301 – Basic Computer Applications 17 15. SEC302 – Business Project Formulation & Entrepreneurship Development 18 16. DSC408 – Intermediate Microeconomics-II 20 17. DSC409 – Intermediate Macroeconomics-II 21 18. DSC410 – Statistics and Econometrics 22 19. SEC403 – Insurance Market and Products 23 20. SEC404 – Tourism Management 24 21. DSC511 – Indian Economy 25 22. DSC512 – Development Economics 26 23. DSE701 – Economics of Health and Education 27 24. DSE702 – Economic History of India (1857-1947) 28 25. DSE703 – Indian Political Economy 29 26. DSE704 – Topics in Public Economics 31 27. DSC613 – International Economics 32 28. DSC614 – Public Economics 33 29. DSE705 – Tribal Economics 35 30. DSE706 – Comparative Economic Development (1850-1950) 36 31. DSE707 – Topics in International Economics 37 32. -

4.1 Uttar Dinajpur: a Brief Profile

4.1 UTTAR DINAJPUR: A BRIEF PROFILE 88"U'IY'E 88''20'0'"E .UTTAR DINAJPUR Roads & Railway Lines 26'20'0~ 26'20'0'1\ ~ J: <( en :I: w m a <( 26"'0'0''N _J 2S'O'O"N (!) z <( OJ 25"40'0~ Dakshin Dinajpur Legend e District & Block Headquater Roads Railways SCALE 25"20'0~ 25'20'0'T• -··-··-··· District Boundary 1:500,000 0 2 4 8 . 12 16 Block Bounqa,ry. Kilometers HRDMS Centre, Uttar Dinajpur. 68'0'D"E 88'20'0'"E 107 North Dinajpur district or Uttar Dinajpur district (uttar meaning North) came into existence on 1992-04-01 after the bifurcation of erstwhile West Dinajpur District by the Gazette Notification No. 177 L.R I 6M-7/92 dated 28.2.1992. It is located in the north of West Bengal. The District lies between latitude 25°11' N to 26°49' Nand longitude 87°49' E to 90°00' E occupying an area of 3142 k:m2 enclosed by Bangladesh on the east, Bihar on the west, Darieeling District and Jalpaiguri District on the north and Maida District and South Dinajpur District on the south. The district is constituted of nine Blocks under two Sub-Divisions namely Raiganj and Islampur. This is a multi-lingual district dominated by Bengali speaking people and there are Urdu and Hindi speaking population in the Islampur area. Uttar Dinajpur is well connected with the rest of the state through National Highways, State Highways and Railways. NH-31 and NH-34 pass through the heart of the district. -

W.B.C.S.(Exe.) Officers of West Bengal Cadre

W.B.C.S.(EXE.) OFFICERS OF WEST BENGAL CADRE Sl Name/Idcode Batch Present Posting Posting Address Mobile/Email No. 1 ARUN KUMAR 1985 COMPULSORY WAITING NABANNA ,SARAT CHATTERJEE 9432877230 SINGH PERSONNEL AND ROAD ,SHIBPUR, (CS1985028 ) ADMINISTRATIVE REFORMS & HOWRAH-711102 Dob- 14-01-1962 E-GOVERNANCE DEPTT. 2 SUVENDU GHOSH 1990 ADDITIONAL DIRECTOR B 18/204, A-B CONNECTOR, +918902267252 (CS1990027 ) B.R.A.I.P.R.D. (TRAINING) KALYANI ,NADIA, WEST suvendughoshsiprd Dob- 21-06-1960 BENGAL 741251 ,PHONE:033 2582 @gmail.com 8161 3 NAMITA ROY 1990 JT. SECY & EX. OFFICIO NABANNA ,14TH FLOOR, 325, +919433746563 MALLICK DIRECTOR SARAT CHATTERJEE (CS1990036 ) INFORMATION & CULTURAL ROAD,HOWRAH-711102 Dob- 28-09-1961 AFFAIRS DEPTT. ,PHONE:2214- 5555,2214-3101 4 MD. ABDUL GANI 1991 SPECIAL SECRETARY MAYUKH BHAVAN, 4TH FLOOR, +919836041082 (CS1991051 ) SUNDARBAN AFFAIRS DEPTT. BIDHANNAGAR, mdabdulgani61@gm Dob- 08-02-1961 KOLKATA-700091 ,PHONE: ail.com 033-2337-3544 5 PARTHA SARATHI 1991 ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER COURT BUILDING, MATHER 9434212636 BANERJEE BURDWAN DIVISION DHAR, GHATAKPARA, (CS1991054 ) CHINSURAH TALUK, HOOGHLY, Dob- 12-01-1964 ,WEST BENGAL 712101 ,PHONE: 033 2680 2170 6 ABHIJIT 1991 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR SHILPA BHAWAN,28,3, PODDAR 9874047447 MUKHOPADHYAY WBSIDC COURT, TIRETTI, KOLKATA, ontaranga.abhijit@g (CS1991058 ) WEST BENGAL 700012 mail.com Dob- 24-12-1963 7 SUJAY SARKAR 1991 DIRECTOR (HR) BIDYUT UNNAYAN BHAVAN 9434961715 (CS1991059 ) WBSEDCL ,3/C BLOCK -LA SECTOR III sujay_piyal@rediff Dob- 22-12-1968 ,SALT LAKE CITY KOL-98, PH- mail.com 23591917 8 LALITA 1991 SECRETARY KHADYA BHAWAN COMPLEX 9433273656 AGARWALA WEST BENGAL INFORMATION ,11A, MIRZA GHALIB ST. agarwalalalita@gma (CS1991060 ) COMMISSION JANBAZAR, TALTALA, il.com Dob- 10-10-1967 KOLKATA-700135 9 MD. -

North Circle - I

Government of West Bengal Public Works Department Establishment Branch Khadya Bhawan 11A,Mirza Ghalib Street,Kolkata -87. No.: 52-E/PWD-11041/2/2020-DIR (PWD) Dated:17.08.2020 NOTIFICATION The Restructuring of various offices under the preview of the Public Works Department has been undertakenvide Notification No.178 dated 20.12.2019. As a result thereof, necessity of re-jurisdiction of Divisions and Sub-Divisions under the Zones of PWD have been felt to cope with the requirement of proper implementation and execution of works relating to restructuring of various offices under Public Works Department. 2. Now, in view of above, the Governor is pleased, in the interest of public service to create re-jurisdiction of Divisionsand Sub-Divisionsunder the Zonesof PWDin the following manner: (AI Rejurisdiction of Divisionand Sub-Division Offices under administrative jurisdiction of North Zone Existing Name of office Name of office by Zonal Chief Jurishdlction of office by Zonal Chief (Division/Sub-Division) Engineer Engineer (Block / Municipality) NORTH CIRCLE - I Coochbehar Division Coochbehar Division-I Coochbehar Sub-Division-I Cooch Behar Sub-Division Eastern part of Dharala river of Cooch Behar-I block inclusive of Cooch Behar Municipality Coochbehar Sub-Dlvlsion-ll Tufanganj Sub-Division Tufanganj-I inclusive of Tufanganj municipality and Tufanganj-II block Dinhata Sub-Division Dinhata Sub-Division Dinhata-I inclusive of Dinhata erstwhile Jorai Costr. Sub- municipality and Dinhata-II block and Division. Sitai block Alipurduar Division Alipurduar Division Alipurduar Sub-Division. Alipurduar Sub-Division Block Alipurduar-I inclusive of Alipurduar Municipality and Eastern part of Kalchini Block consisting of Buxa and Jayanti Notification No: 52-E/PWD-ll041/2/2020-DIR (PWD) dated 17.08.2020 Rejurisdiction of Division and Sub-Division Offices under administrative jurisdiction of North Zone Existing Name of office Name of office by Zonal Chief lurishdiction of office by Zonal Chief (Division/Sub-Division) Engineer Engineer (Block / Municipality) Kamakhyaguri Constr. -

Chapter 2: Historical and Geographical Background of the Study Area

Chapter 2: Historical and Geographical Background of the Study Area 2.1. Historical Background: Bifurcation of the erstwhile district West Dinajpur on 1st April in the year 1992 gave birth of Uttar Dinajpur District, a narrow strip of land between Bihar and Bangladesh extending from north to south, bounded to the north by district Darjeeling, on the east by Bangladesh, in the south by the district of Dakshin Dinajpur and in the West by the district of Malda, also by Kishanganj, Katihar & Purnea Districts of Bihar. The district is subdivided into two subdivisions viz. Raiganj and Islampur. In 1947, Dinajpur district was divided into namely Dinajpur (now in Bangladesh) and West Dinajpur (jointly Uttar and Dakshin Dinajpur districts). It is said that according to the name of King Danuj @ Dinaj, the erstwhile Dinajpur district was named. 2.2. Location of the study area: Uttar Dinajpur district lies within the coordinate of latitude 25°11' N to 26°49' N and longitude 87°49'E to 90°00'E occupying an area of 3142 km² enclosed by Panchagarh, Thakurgaon and Dinajpur district of Bangladesh in the east, Kishanganj, Purnia and Katihar districts of Bihar on the west, Darjeeling district and Jalpaiguri district on the north and Malda district and Dakshin Dinajpur district on the south. 2.3. Administrative division: The district has been subdivided into two sub-divisions viz. Raiganj and Islampur, 110 km (68 mi) apart from each other and comprising mainly of Bengali speaking population while Islampur has a large number of Urdu and Hindi speaking people. There are 4 Municipalities, 9 Blocks and 97 Panchayats covering 3263 inhabited villages. -

Dakshin Dinajpur Merit List

NATIONAL MEANS‐CUM ‐MERIT SCHOLARSHIP EXAMINATION,2019 PAGE NO.1/10 GOVT. OF WEST BENGAL DIRECTORATE OF SCHOOL EDUCATION SCHOOL DISTRICT AND NAME WISE MERIT LIST OF SELECTED CANDIDATES CLASS‐VIII NAME OF ADDRESS OF ADDRESS OF QUOTA UDISE NAME OF SCHOOL DISABILITY MAT SAT SLNO ROLL NO. THE THE THE GENDER CASTE TOTAL DISTRICT CODE THE SCHOOL DISTRICT STATUS MARKS MARKS CANDIDATE CANDIDATE SCHOOL SHAORA TALA NEAR DURGAMANDAP,KUSHMANDI,KUS DAKSHIN KUSHMANDI HIGH WEST DAKSHIN 1 123193702042 ABHIJIT SARKAR 19050800102 M SC None 57 65 122 HMANDI DAKSHIN DINAJPUR DINAJPUR SCHOOL BENGAL DINAJPUR 733132 BAODHARA,RAJUA,BALURGHAT DAKSHIN WEST DAKSHIN 2 123193701154 AFCHHANA MIMI 19050614402 RAJUA S.S.HIGH SCHOOL F GENERAL None 45 59 104 DAKSHIN DINAJPUR 733102 DINAJPUR BENGAL DINAJPUR AFRIN HOSSAIN TELIPUKUR,BASAIL,KUSHMANDI DAKSHIN KUSHMANDI HIGH WEST DAKSHIN 3 123193702085 19050800102 F GENERAL None 56 56 112 TANVI DAKSHIN DINAJPUR 733132 DINAJPUR SCHOOL BENGAL DINAJPUR BALARAMVITA,SINGADAHA,BANSHI DAKSHIN GANGURIA HIGH SCHOOL WEST DAKSHIN 4 123193702106 AKASH ROY 19050504803 M SC None 35 37 72 HARI DAKSHIN DINAJPUR 733125 DINAJPUR (H.S) BENGAL DINAJPUR AKKHAY KUMAR NAYABAZAR,NAYABAZAR,TAPAN DAKSHIN SAYRAPUR KMV HIGH WEST DAKSHIN 5 123193702019 19050307302 M SC None 36 36 72 SARKAR DAKSHIN DINAJPUR 733142 DINAJPUR SCHOOL BENGAL DINAJPUR JOYPUR,JOYPUR,GANGARAMPUR DAKSHIN SAYRAPUR KMV HIGH WEST DAKSHIN 6 123193702016 ANAMIKA SARKAR 19050307302 F SC None 36 43 79 DAKSHIN DINAJPUR 733142 DINAJPUR SCHOOL BENGAL DINAJPUR KUMARGRAM,THAKURPURA,BALU DAKSHIN -

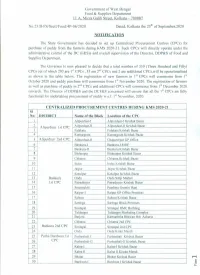

Notification on CPC.Pdf

Government of West Bengal Food & Supplies Department 11 A, Mirza Galib Street, Kolkata - 700087 No.2318-FS/Sectt/Food/4P-06/2020 Dated, Kolkata the zs" of September,2020 NOTIFICATION The State Government has decided to set up Centralized Procurement Centres (CPCs) for purchase of paddy from the farmers during KMS 2020-21. Such CPCs will directly operate under the administrative control of the DC (F&S)s and overall supervision of the Director, DDP&S of Food and Supplies Department. The Governor is now pleased to decide that a total number of 350 (Three Hundred and Fifty) nd CPCs out of which 293 are 1st CPCs ,55 are 2 CPCs and 2 are additional CPCs,will be operationalised as shown in the table below. The registration of new farmers in 1st CPCs will commence from 1sI October 2020 and paddy purchase will commence from 1st November 2020. The registration of farmers nd as well as purchase of paddy in 2 CPCs and additional CPCs will commence from 1st December 2020 onwards. The Director of DDP&S and the DCF&S concerned will ensure that all the 1st CPCs are fully functional for undertaking procurement of paddy w.e.f. 1st November, 2020. CENTRALIZED PROCUREMENT CENTRES DURING KMS 2020-21 SI No: DISTRICT Name ofthe Block Location of the CPC f--- 1 Alipurduar-I Alipurduar-I Krishak Bazar 2 Alipurduar-II Alipurduar-II Krishak Bazar f--- Alipurduar 1st CPC - 3 Falakata Falakata Krishak Bazar 4 Kurnarzram Kumarzram Krishak Bazar 5 Alipurduar 2nd Cf'C Alipurduar-Il Chaporerpar GP Office - 6 Bankura-l Bankura-I RlDF f--- 7 Bankura-II Bankura Krishak Bazar I--- 8 Bishnupur Bishnupur Krishak Bazar I--- 9 Chhatna Chhatna Krishak Bazar 10 - Indus Indus Krishak Bazar ..».