In the Gates of Israel Herman Bernstein

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Jewish Yearbook

JEWISH STATISTICS 277 JEWISH STATISTICS The statistics of Jews in the world rest largely upon estimates. In Russia, Austria-Hungary, Germany, and a few other countries, official figures are obtainable. In the main, however, the num- bers given are based upon estimates repeated and added to by one statistical authority after another. For the statistics given below various authorities have been consulted, among them the " Statesman's Year Book" for 1910, the English " Jewish Year Book " for 5670-71, " The Jewish Ency- clopedia," Jildische Statistik, and the Alliance Israelite Uni- verselle reports. THE UNITED STATES ESTIMATES As the census of the United States has, in accordance with the spirit of American institutions, taken no heed of the religious convictions of American citizens, whether native-born or natural- ized, all statements concerning the number of Jews living in this country are based upon estimates. The Jewish population was estimated— In 1818 by Mordecai M. Noah at 3,000 In 1824 by Solomon Etting at 6,000 In 1826 by Isaac C. Harby at 6,000 In 1840 by the American Almanac at 15,000 In 1848 by M. A. Berk at 50,000 In 1880 by Wm. B. Hackenburg at 230,257 In 1888 by Isaac Markens at 400,000 In 1897 by David Sulzberger at 937,800 In 1905 by "The Jewish Encyclopedia" at 1,508,435 In 1907 by " The American Jewish Year Book " at 1,777,185 In 1910 by " The American Je\rish Year Book" at 2,044,762 DISTRIBUTION The following table by States presents two sets of estimates. -

Campaign and Transition Collection: 1928

HERBERT HOOVER PAPERS CAMPAIGN LITERATURE SERIES, 1925-1928 16 linear feet (31 manuscript boxes and 7 card boxes) Herbert Hoover Presidential Library 151 Campaign Literature – General 152-156 Campaign Literature by Title 157-162 Press Releases Arranged Chronologically 163-164 Campaign Literature by Publisher 165-180 Press Releases Arranged by Subject 181-188 National Who’s Who Poll Box Contents 151 Campaign Literature – General California Elephant Campaign Feature Service Campaign Series 1928 (numerical index) Cartoons (2 folders, includes Satterfield) Clipsheets Editorial Digest Editorials Form Letters Highlights on Hoover Booklets Massachusetts Elephant Political Advertisements Political Features – NY State Republican Editorial Committee Posters Editorial Committee Progressive Magazine 1928 Republic Bulletin Republican Feature Service Republican National Committee Press Division pamphlets by Arch Kirchoffer Series. Previously Marked Women's Page Service Unpublished 152 Campaign Literature – Alphabetical by Title Abstract of Address by Robert L. Owen (oversize, brittle) Achievements and Public Services of Herbert Hoover Address of Acceptance by Charles Curtis Address of Acceptance by Herbert Hoover Address of John H. Bartlett (Herbert Hoover and the American Home), Oct 2, 1928 Address of Charles D., Dawes, Oct 22, 1928 Address by Simeon D. Fess, Dec 6, 1927 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – Boston, Massachusetts, Oct 15, 1928 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – Elizabethton, Tennessee. Oct 6, 1928 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – New York, New York, Oct 22, 1928 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – Newark, New Jersey, Sep 17, 1928 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – St. Louis, Missouri, Nov 2, 1928 Address of W. M. Jardine, Oct. 4, 1928 Address of John L. McNabb, June 14, 1928 Address of U. -

A Study in American Jewish Leadership

Cohen: Jacob H Schiff page i Jacob H. Schiff Cohen: Jacob H Schiff page ii blank DES: frontis is eps from PDF file and at 74% to fit print area. Cohen: Jacob H Schiff page iii Jacob H. Schiff A Study in American Jewish Leadership Naomi W. Cohen Published with the support of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America and the American Jewish Committee Brandeis University Press Published by University Press of New England Hanover and London Cohen: Jacob H Schiff page iv Brandeis University Press Published by University Press of New England, Hanover, NH 03755 © 1999 by Brandeis University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 54321 UNIVERSITY PRESS OF NEW ENGLAND publishes books under its own imprint and is the publisher for Brandeis University Press, Dartmouth College, Middlebury College Press, University of New Hampshire, Tufts University, and Wesleyan University Press. library of congress cataloging-in-publication data Cohen, Naomi Wiener Jacob H. Schiff : a study in American Jewish leadership / by Naomi W. Cohen. p. cm. — (Brandeis series in American Jewish history, culture, and life) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-87451-948-9 (cl. : alk. paper) 1. Schiff, Jacob H. (Jacob Henry), 1847-1920. 2. Jews—United States Biography. 3. Jewish capitalists and financiers—United States—Biography. 4. Philanthropists—United States Biography. 5. Jews—United States—Politics and government. 6. United States Biography. I. Title. II. Series. e184.37.s37c64 1999 332'.092—dc21 [B] 99–30392 frontispiece Image of Jacob Henry Schiff. American Jewish Historical Society, Waltham, Massachusetts, and New York, New York. -

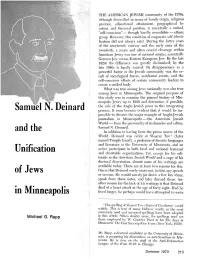

Samuel N. Deinard and the Unification of Jews in Minneapolis / Michael G

THE AMERICAN JEWISH community of the 1970s, although diversified in terms of family origin, rehgious practice, educational attainment, geographical lo cation, and financial position, is essentially a united, "self-conscious" — though hardly monolithic — ethnic group. However, this condition of corporate self-identi fication did not always exist. During the latter years of the nineteenth century and the early ones of the twentieth, a major and often crucial cleavage within American Jewry was one of national origins, essentially German Jew versus Eastern European Jew. By the late 1920s the difference was greatly diminished; by the late 1940s it hardly existed. Its disappearance as a powerful factor in the Jewish community was the re sult of sociological forces, accidental events, and the self-conscious efforts of certain community leaders to create a unified body. What was true among Jews nationally was also true among Jews in Minneapolis. The original purpose of this study was to examine the general history of Min neapolis Jewry up to 1922 and determine, if possible, the role of the Anglo-Jewish press in this integrating Samuel N. Deinard process. It soon became evident that it would be im possible to divorce the major example of Anglo-Jewish journalism in Minneapolis — the American Jewish World — from the personality of its founder and editor, Samuel N. Deinard. and the In addition to having been the prime mover of the World, Deinard was rabbi at Shaarai Tov^ (later named Temple Israel), a professor of Semitic languages and literature at the University of Minnesota, and an active participant in both local and national fraternal Unification and charitable organizations. -

Volume 43, Issue 2 (The Sentinel, 1911

THE SENTINEL American Jews Give One Million Dollars For Money to Your Palestine In 3 Months. Relative: in Europe. Dr. Weizmann Leaves for Europe. We have our own direct connections New York (J. C. B.)-After a stay to America makes possible the found- for sending money by mail or cable to of approximately three months, during ing of Jewish Agrarian Bank in Pal- POLAND LITHUANIA which time he visited the larger Jew- estine which will be opened as soon as LATVIA ROUMANIA ish centers in the United States and the necessary preliminaries have been BESSARABIA Canada in the interest of the Keren gone through. Hayesod, Dr. Chaim Weizmann, Pres- At a farewell meeting in Carnegie and other parts of the world. ident of the World Zionist Organiza- iall, Dr. Weizmann touched on the We also send t'on, left for Europe on board the present diplomatic status of Zionist af- "Celtic" on Saturday, June 26. fairs and said: DOLLARS TO0 POLAND On the afternoon before, Dr. Weiz- "No one is to doubt and no one is through our own office. mann entertained the Jewish journal- to fear that the Balfour Declaration ists of New York City at a luncheon thSaReodcsnwilihr STEAMSHIP TICKET- in the Hotel Commodore. The Zionist drtet nRmodcsinwllete sent by mail or cable. leader expressed his sincere thanks to dircty or indirectly be modified. The the Yiddish and English-Jewish press rromiseg ivzeuswyrat Britan rand of the country for making possible tewhco ciiiedesworldi a rpok SCH1lI 0COMPANYSTATE BANK what success he has met with in thiswhccantbderodndun Cigarette R~oosevelt Poad near Haisted country. -

Albania: the Country That Actually Saved Jews During the Holocaust

Albania: The Country That Actually Saved Jews During the Holocaust Stephen D. Kulla Gratz College Situated on the Balkan Peninsula in Southeast Europe, with its coastline facing the Adriatic Sea to the northwest and the Ionian Sea to the southwest along the Mediterranean Sea, sits the country of Albania. Albanians are generally recognized as the oldest inhabitants of Southeast Europe, and are descendants of the Illyrians, the core pre-Hellenic population that 1 extended as far as Greece and Italy. Albania is a relatively small county of 11,000 square miles with a present population of just under three million people; yet within the mountains and hills that run in different directions across the length and breadth of the country lies a little-known 2 story of preeminent heroism. Despite being a predominantly Muslim nation and the only majority Muslim nation in Europe at the time, Albania is the only European country able to 3 arguably claim that every Jew within its borders was spared from death during the Holocaust. 4 The assertion, while not completely accurate, is even more compelling because the result was unequivocally not due to an organized effort, nor by a governmental decree. It was, however, surely not accidental. Despite being occupied by Italy and then Germany during World War II and being ruled at different times by two very distinctive forms of government, Albania not only 5 protected its meager Jewish population, but offered refuge to Jews from wherever they came. The explanation for this occurrence is greatly summed up in one word: Besa, an honor code 6 unique to Albania, which simply and concisely means “to keep the promise.” On the eve of World War II, Albania remained an impoverished feudal kingdom, largely inaccessible, lacking railways, telephone lines and electric power beyond the capital of Tirana. -

Henry Ford's Anti-Semitism: a Rhetorical Analysis of the "Paranoid" Style

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-1999 Henry Ford's anti-Semitism: A rhetorical analysis of the "paranoid" style Jeffrey Brian Farrell University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Farrell, Jeffrey Brian, "Henry Ford's anti-Semitism: A rhetorical analysis of the "paranoid" style" (1999). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 968. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/wfo5-e1b5 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. -

The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, Food Donations and Jewish American Identity During and After World War I Taylor Dwyer Chapman University

Voces Novae Volume 8 Article 3 2018 "I've Had A Bully Good Feed!” and “I'm Waiting in the Bread Line for Mine!": The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, Food Donations and Jewish American Identity during and after World War I Taylor Dwyer Chapman University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/vocesnovae Recommended Citation Dwyer, Taylor (2018) ""I've Had A Bully Good Feed!” and “I'm Waiting in the Bread Line for Mine!": The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, Food Donations and Jewish American Identity during and after World War I," Voces Novae: Vol. 8 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/vocesnovae/vol8/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Voces Novae by an authorized editor of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dwyer: "I've Had A Bully Good Feed!” and “I'm Waiting in the Bread Line "I've Had A Bully Good Feed!” and “I'm Waiting in the Bread Line for Mine!" Voces Novae: Chapman University Historical Review, Vol 8, No 1 (2016) HOME ABOUT USER HOME SEARCH CURRENT ARCHIVES PHI ALPHA THETA Home > Vol 8, No 1 (2016) "I've Had A Bully Good Feed!” and “I'm Waiting in the Bread Line for Mine!": The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, Food Donations and Jewish American Identity during and after World War I Taylor Dwyer American Jews were far from a homogenous, singular community at the brink of World War I. -

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Blood and Ink: Russian and Soviet Jewish Chroniclers of Catastrophe from World War I to World War II Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/48x3j58s Author Zavadivker, Polly Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ BLOOD AND INK: RUSSIAN AND SOVIET JEWISH CHRONICLERS OF CATASTROPHE FROM WORLD WAR I TO WORLD WAR II A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY by Polly M. Zavadivker June 2013 The Dissertation of Polly M. Zavadivker is approved: ______________________________ Professor Nathaniel Deutsch, Chair _______________________________ Professor Murray Baumgarten _______________________________ Professor Peter Kenez _____________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Polly M. Zavadivker 2013 Table of Contents Table of Contents iii Abstract iv Dedication vi Acknowledgements vii Introduction Witnesses to War: Russian and Soviet Jews as 1 Chroniclers of Catastrophe, 1914-1945 Chapter 1 Fighting 'On Our Own Territory': The Relief, Rescue and 54 Representation of Jews in Russia during World War I Chapter 2 The Witness as Translator: S. An-sky's 1915 88 War Diary and Postwar Memoir, Khurbn Galitsye Chapter 3 Reconstructing a Lost Archive: Simon Dubnov and 128 'The Black Book of Imperial Russian Jewry,' 1914-1915 Chapter 4 Witness Behind a Mask: Isaac Babel and the 158 Polish-Bolshevik War , 1920 Chapter 5 To Carry the Burden Together: Vasily Grossman 199 as Chronicler of Jewish Catastrophe, 1941-1945 Conclusion The Face of War, 1914-1945 270 Bibliography 278 iii Abstract Polly M. -

The Leo Frank Affair As a Turning Point in Jewish-American History

The Yahudim and the Americans: The Leo Frank Affair as a Turning Point in Jewish-American History Jason Schulman Columbia University Historians have often described the Jewish-American past as exceptional, mostly because anti-Semitism has played a conspicuously less important role in America than in any other country in the Diaspora. As American Jewish historian Jonathan Sarna concludes, if the United States “has not been utter heaven for Jews, it has been as far from hell as Jews in the Diaspora have ever known.”1 If such a statement is true, then the Leo Frank affair becomes even more egregious in Jewish American history. For Jews who had come to see America as the land of unencumbered opportunity, the “Goldene Medina,” the false conviction and subsequent lynching of a prominent Jew in Atlanta in 1913 resembled contemporaneous anti-Semitic attacks in Europe. Looking back on this incident from a Jewish as well as an American perspective, and despite admirable attempts by previous historians to make sense of this muddled event, the Frank affair has not been given proper attention. Typically, historians seeking to stress the ease with which Jewish immigrants became “Americanized” have ignored or downplayed the Frank affair, while even those historians who acknowledge the severity of the anti-Semitic event have failed to grasp its widespread significance; for the latter group, the Leo Frank affair was an isolated southern incident.2 The Leo Frank affair is arguably the single-most loaded event in Jewish American history, touching on multiple issues that have defined the rise of Jews in America: “Americanization,” labor, upward mobility, gender, immigration, nativism, and anti-Semitism.3 The facts of the Leo Frank “affair,” the term employed by Albert Lindemann to describe Frank’s conviction, imprisonment, and lynching, are clear.4 In April 1913, Leo Frank, the superintendent of a pencil factory in Atlanta, was arrested for the murder of Mary Phagan, a child laborer in the factory. -

Transatlantica, 2 | 2010 Edsel Ford: the Businessman As Artist 2

Transatlantica Revue d’études américaines. American Studies Journal 2 | 2010 The Businessman as Artist / New American Voices Edsel Ford: The Businessman as Artist A Wealth of Creative Abilities John Dean Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/5175 DOI: 10.4000/transatlantica.5175 ISSN: 1765-2766 Publisher Association française d'Etudes Américaines (AFEA) Electronic reference John Dean, “Edsel Ford: The Businessman as Artist”, Transatlantica [Online], 2 | 2010, Online since 15 April 2011, connection on 18 May 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/5175 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/transatlantica.5175 This text was automatically generated on 18 May 2021. Transatlantica – Revue d'études américaines est mise à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Edsel Ford: The Businessman as Artist 1 Edsel Ford: The Businessman as Artist A Wealth of Creative Abilities John Dean 1 This essay’s objective is to examine an overlooked, outstanding example of the businessman as artist, Edsel Bryant Ford. To consider his skill as automobile designer; his forceful, innovative management of advertising and public relations; his adept painting, sculpting and photography; his exceptional sense of personal elegance; the creation by his wife and himself of a remarkable personal residence; his philanthropic enterprises; his challenging, adroit and often deeply frustrating dealings with his own father Henry Ford; and, last but not least, his use of Diego Rivera—a man strangely misunderstood in his own time as the artist who did not do business. 2 Edsel Ford’s life story happened in a unique American city, Detroit, Michigan, which the late New York Times journalist R. -

Download PDF Catalogue

F i n e Ju d a i C a . he b r e w pr i n t e d bo o K s , ma n u s C r i p t s , Gr a p h i C & Ce r e m o n i a l ar t in C l u d i n G : th e al F o n s o Ca s s u t o Co l l e C t i o n o F ib e r i a n -Ju d a i C a K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y th u r s d a y , Fe b r u a r y 24t h , 2011 K e s t e n b a u m & Co m p a n y . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 264 Catalogue of F i n e Ju d a i C a . PRINTED BOOKS , MANUSCRI P TS , AUTOGRA P H LETTERS , GRA P HIC & CERE M ONIA L ART Featuring: Iberian Judaica The Distinguished Collection of the late Alfonso Cassuto of Lisbon, Portugal ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Thursday, 24th February, 2011 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, 20th February - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday, 21st February - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Tuesday, 22nd February - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Wednesday 23rd February - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm No viewing on the day of sale.