Brief of T'ruah and J Street As Amici Curiae in Support of Plaintiff

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

J Street's Role As a Broker

J Street’s Role as a Broker: Is J Street Expanding the Reach of the Organized American Jewish Community? Emily Duhovny Senior Honors Thesis Submitted to Organizational Studies University of Michigan Advisor: Michael T. Heaney March 11, 2011 1 Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor Michael Heaney for inspiring me to write a thesis and for working with me every step of the way. Since our first meeting in the fall of 2009, Michael has been a remarkable mentor. In his lab group, he introduced me to the methods of organizational studies and political science research. In his classroom, he engaged my class on interest group politics and inspired me to select a thesis topic connected to interest groups. Now, as my faculty mentor for my senior honors thesis, he has dedicated many hours assisting me and answering my myriad of questions. I am especially grateful for the times when he pushed me to take responsibility for my work by encouraging me to be confident enough to make my own decisions. I would also like to thank my family and friends who have learned more about J Street and the American Jewish community then they ever could have possibly wanted to know. I especially want to thank my parents and Grandma Ruth for their love and support. Thank you to my dad, who has taught me that it is better to “think big” and risk failure than to not have tried at all. He has not only been a great sounding board, but also has challenged me to defend my views. -

J Street Sides with Israel's Enemies & Works to Destroy Support for Israel

ZIONIST ORGANIZATION OF AMERICA J Street Sides With Israel’s Enemies & Works to Destroy Support for Israel Special Report Including Executive Summary by The Zionist Organization of America by Morton A. Klein, Elizabeth Berney, Esq., and Daniel Mandel, PhD “J Street is one of the most virulent anti-Israel organizations in the history of Zionism and Judaism.” - Prof. Alan Dershowitz, Harvard Law School Copyright 2018, Zionist Organization of America CONTENTS Table of Contents . i Executive Summary . ES-00 - ES-13 Full Report . 1 Introduction . 1 I. J Street’s Anti-Israel, Foreign & Muslim Donors, and Its Lies About Them. 1 (1) For years, J Street Falsely Denied that Anti-Zionist Billionaire George Soros Was A Major J Street Funder . 1 (2) J Street’s Arab, Muslim and Foreign Donors . 4 II. J Street’s Interconnected Web Of Extremist Anti-Israel Organizations . 9 (1) J Street Is Part of a Soros-Funded Web of Anti-Israel Organizations . 9 (2) J Street Is Also Part of an Interconnected Web of Extremist Organizations Working to Delegitimize Israel, Founded by and/or Coordinated by J Street President Ben-Ami’s Consulting Firm . 11 III. J Street Persistently Even Opposes Israel’s Existence, Persistently Defames and Condemns Israel, And Has Even Encouraged Anti-Israel Violence. 12 (1) J Street Persistently Maligns and Blames Israel . 12 (2) J Street Speakers Have Called for the End of the Jewish State; and a J Street Official Letter to Congress Supported Those Calling for an End to Israel’s Existence . 15 (3) J Street’s Co-Founder Condemned Israel’s Creation As “Wrong” – A Repeated J Street Theme . -

26Th Annual Julian Y. Bernstein Distinguished Service Awards Ceremony 2021/5781

7:30pm 4 Nisan 5781 Nisan 4 Tuesday, March 16, 2021 16, March Tuesday, AWARDS CEREMONY AWARDS DISTINGUISHED SERVICE DISTINGUISHED JULIAN Y. BERNSTEIN Y. JULIAN ANNUAL th 26 WESTCHESTER JEWISH COUNCIL Connect Here® Academy for Jewish Religion Hebrew Free Loan Society Sanctuary ACHI - American Communities Helping Israel Hebrew Institute of White Plains Scarsdale Synagogue - Temples - Tremont AIPAC - American Israel Public Affairs Committee HIAS and Emanu-El AJC Westchester/Fairfield Hillels of Westchester Shaarei Tikvah Ameinu, Project Rozana Holocaust & Human Rights Education Center Shalom Hartman Institute of North America American Friends of Magen David Adom ImpactIsrael Shames JCC on the Hudson American Friends of Soroka Medical Center Israel Bonds (Development Corporation for Israel) Sinai Free Synagogue American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) Israel Policy Forum Students & Parents Against Campus American Zionist Movement (AZM) J Street Anti-Semitism (SPACA) Anti-Defamation League (ADL) JCCA Sprout Westchester Areyvut The Jewish Board StandWithUs BBYO Westchester Region Jewish Broadcasting Services (JBS) Stein Yeshiva of Lincoln Park Bet Am Shalom Synagogue Jewish Community Center of Harrison Temple Beth Abraham Bet Torah Jewish Community Center of Mid-Westchester Temple Beth Am Beth El Synagogue Center Jewish Community Council of Mt. Vernon Temple Beth El of Northern Westchester The Blue Card Jewish Deaf (and Hard-of-Hearing) Resource Temple Beth El – Danbury Bronx Jewish Community Council, Inc Center Temple Beth Shalom - Hastings Camp Zeke The Jewish Education Project Temple Beth Shalom - Mahopac Chabad Center for Jewish Life of the Rivertowns Jewish National Fund of Temple Israel Center of White Plains Chabad of Bedford Westchester & Southern CT Temple Israel of New Rochelle Chabad Lubavitch of Larchmont and Mamaroneck Jewish Theological Seminary Temple Israel of Northern Westchester Chavurat Tikvah Justice Brandeis Westchester Law Society Temple Shaaray Tefila of Westchester Children’s Jewish Education Group Keren Or, Inc. -

Jewish Journal February 2017

The Jewish Journal is for Kids, too! Check out Kiddie Corner, PAGE 26-27 The Jewish Journalof san antonio SH’VAT - ADAR 5777 Published by The Jewish Federation of San Antonio FEBRUARY 2017 Former Chief Rabbi of Israel to visit San Antonio and speak at Rodfei Sholom Rabbi Yisrael Meir Lau will be visiting unimaginable hardship. In 2005, Lau was San Antonio February 10 – 12. He will be awarded the Israel Prize for his lifetime KICKING THINGS the scholar in residence and guest speaker achievements and special contribution to UP A NOTCH IN 2017 at Congregation Rodfei Sholom. society and the State of Israel. On April 14, See What’s Happening Rabbi Lau is the Chairman of Yad 2011, he was awarded the Legion of Honor in YOUR San Antonio Vashem and Chief Rabbi of Tel Aviv. He (France’s highest accolade) by French Jewish Community, previously served as the Ashkenazi Chief President Nicolas Sarkozy, in recognition Rabbi of Israel. His father, Rabbi Moshe of his efforts to promote interfaith PAGES 14 - 21 Chaim Lau, was the last Chief Rabbi of the dialogue. Polish town of Piotrkow. At age 9, Rabbi Rabbi Yisrael Meir Lau will be visiting San Antonio Rabbi Lau’s bestselling autobiography, PARTNERS Lau was the youngest person liberated February 10 – 12. Out of the Depths, tells the story of his TOGETHER: from the Buchenwald concentration tale of triumph and faith as a young boy miraculous journey from an orphaned COMING SOON camp, and he came on the first boatload during the Holocaust provides us with a Plans underway to of Holocaust survivors to Israel. -

NEW POLL: Majority of American Jews Support Iran Nuclear Deal

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 28, 2015 CONTACT: Jessica Rosenblum, [email protected], 202.448.1600/202.279.0005 (m) NEW POLL: Majority of American Jews Support Iran Nuclear Deal WASHINGTON—The majority of American Jews support the Iran nuclear deal and do so at a higher rate than Americans as a whole, according to a new poll. The poll, conducted by Jim Gerstein of GBA Strategies and released today by J Street, finds that 60 percent of American Jews support the agreement reached between the P5+1 and Iran. This, as compared to the 56 percent of American adults who backed the deal when asked the exact same question in a July 20 Washington Post-ABC poll. “These results make clear that American Jews overwhelmingly support this deal and see this diplomatic agreement as the best way to keep Iran from getting a nuclear weapon,” says J Street President Jeremy Ben-Ami. “The numbers just go to show—once again— that the pundits and those who speak most loudly on behalf of the Jewish community are flat- out wrong in their presumption that Jewish Americans are hawkish on Iran or regarding U.S. policy in the Middle East in general.” The full survey, crosstabs and analysis can be found here. As a fierce battle over the deal between pro-Israel advocacy organizations takes shape on Capitol Hill, American Jews want their Members of Congress to approve the agreement by the same 20-point margin, 60 to 40 percent. Support for the agreement cuts across demographic groups. There is broad and, in most cases, majority support for the agreement across the Jewish community, regardless of age, gender, region, Jewish organizational engagement and knowledge of the issue. -

Jewish News Issue 3 | Volume XL | May & June 2015

Columbia Jewish News Issue 3 | Volume XL | May & June 2015 Camp Gesher: The Best-Kept Reports from AIPAC Summer Camp Secret and J Street see page 7 see page 9 Permit No. 48 No. Permit RETURN SERVICE REQUESTED SERVICE RETURN Columbia, SC Columbia, Columbia, SC 29223 SC Columbia, PAID US Postage US 306 Flora Drive Flora 306 Non Profit Org Profit Non Columbia Jewish Federation Jewish Columbia The Secret to Jewish Immortality The Columbia Jewish News is a bi-monthly Barry Abels, CJF and JCC Executive Director publication of the Columbia Jewish Federation. Soon we will be observing Shavuot, the receiving of the Ten Commandments and the Torah at Mount Sinai. This critical event in our history was the point where we, the Jewish people, became a nation. This nation would continue to experience challenges and major trials, but would Columbia Jewish Federation also come to make a mark on the world. 306 Flora Drive This is as true today as in times past. I am Columbia, SC 29223 reminded of the words of Mark Twain in reference to our Jewish people: t (803) 787-2023 | f (803) 462-1337 www.jewishcolumbia.org “All things are mortal but the Jews; all other forces pass, but he remains. What is the secret of his immortality?” Columbia Jewish Federation Staff Barry Abels, Executive Director In the previous Jewish News I discussed our belief in the value of life. [email protected], ext. 207 That explicit cultural value is one of many the many “secrets” Mark Elaine Cohen, Jewish Family Service Director Twain pondered. -

1 Morton Klein of the Zionist Organization of America (ZOA) and Candace Owens of Turning Point USA Will Be Testifying at a Congr

Morton Klein of the Zionist Organization of America (ZOA) and Candace Owens of Turning Point USA will be testifying at a congressional hearing on hate crime. Not only does neither individual possess any expertise on the matter, they have also both engaged in bigoted and incendiary rhetoric that disqualifies them from engaging productively on the subJect. Morton Klein: In 2018, Klein compared Arabs to Nazis, and doubled down on his use of “filthy Arab” as a slur he found legitimate. Morton Klein came to the defense of Jeanine Pirro after Fox News condemns her anti-Muslim comments suggesting the HiJab is a sign of disloyalty to the United States: 1 Klein also called for the U.S. to adopt Israel’s discriminatory policies that profile on the basis of faith and background, saying: “we should adopt the same profiling policies as Israel and be more thorough in vetting Muslims.” Morton Klein leveled sexist attack on Harvard-educated actress Natalie Portman, suggesting she was attractive but stupid, over her criticism of BenJamin Netanyahu: 2 Klein regularly attacks more established Jewish organizations for failing to seemingly engage in bigoted attacks. Here, he makes the baseless allegation that the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) does not condemn the murder of Jews by Arabs: Klein also attacks the ADL by accusing them of “promoting Black Lives Matter and … the extremist anti-Israel group J Street,” prompting criticism from the Conference of Presidents of MaJor American Jewish Organizations: 3 When Fox News host Jeanine Pirro found herself in hot water a few weeks ago, after suggesting that American Muslims who wear a HiJab (including an American Muslim Congresswoman) could not be loyal to the United States, Morton Klein tweeted his support for Pirro’s comments. -

Jeremy Versus Goliath J Street’S Brave Effort to Promote Peace in the Middle East by Scott Macleod

Books Jeremy Versus Goliath J Street’s Brave Effort to Promote Peace in the Middle East By Scott MacLeod A New Voice for Israel: Fighting for the Survival of the Jewish Nation. By Jeremy Ben-Ami. Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. 242 pp. eremy Ben-Ami has written a valuable book that should be read by everyone affected Jby the Israeli–Palestinian conflict—Israelis, Arabs and especially by Americans. The title may suggest to some that this is another volume of familiar pro-Israel boosterism. The author believes that Israel’s existence is under threat and this is the focus of his effort. Yet, he has written a very different sort of book than we are used to seeing from Israel’s die-hard supporters in America. Part of A New Voice for Israel is an account of the deep roots of Ben-Ami’s family in Israel. The book also serves as an insider’s guide to J Street, the pro-Israel lobby group that Ben-Ami founded in 2008. In that aspect, he tells the story of a struggle under way for the soul of America’s Jewish community, and J Street’s role in it. At its core, Ben-Ami’s book, like J Street’s work, is a courageous effort to rewrite the Israel- driven narrative of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict that is too unquestioningly accepted and parroted in the West. This is an impassioned plea for American Jews, U.S. politicians, and Israelis to get on the right side of history in the Middle East. Ben-Ami debunks the mythology about Israel’s founding, embraces the need for a peace settlement that provides dignity and jus- tice to the Palestinians, criticizes Israeli politics for undemocratic tendencies, and blasts Washington’s uncritical support for Israeli policies. -

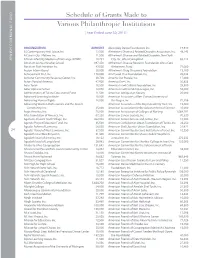

Schedule of Grants Made to Various

Schedule of Grants Made to Various Philanthropic Institutions [ Year Ended June 30, 2015 ] ORGANIZATION AMOUNT Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. 19,930 3S Contemporary Arts Space, Inc. 12,500 Alzheimer’s Disease & Related Disorders Association, Inc. 46,245 A Cure in Our Lifetime, Inc. 11,500 Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders, New York A Torah Infertility Medium of Exchange (ATIME) 20,731 City, Inc. d/b/a CaringKind 65,215 Abraham Joshua Heschel School 397,450 Alzheimer’s Disease Research Foundation d/b/a Cure JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND JEWISH COMMUNAL Abraham Path Initiative, Inc. 42,500 Alzheimer’s Fund 71,000 Accion International 30,000 Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation 15,100 Achievement First, Inc. 170,000 Am Yisroel Chai Foundation, Inc. 25,036 Achiezer Community Resource Center, Inc. 20,728 Ameinu Our People, Inc. 17,000 Actors Fund of America 47,900 America Gives, Inc. 30,856 Adas Torah 16,500 America-Israel Cultural Foundation, Inc. 25,500 Adler Aphasia Center 14,050 America-Israel Friendship League, Inc. 55,000 Administrators of Tulane Educational Fund 11,500 American Antiquarian Society 25,000 Advanced Learning Institute 10,000 American Associates of Ben-Gurion University of Advancing Human Rights 18,000 the Negev, Inc. 71,386 Advancing Women Professionals and the Jewish American Associates of the Royal Academy Trust, Inc. 15,000 Community, Inc. 25,000 American Association for the Advancement of Science 35,000 Aegis America, Inc. 75,000 American Association of Colleges of Nursing 1,064,797 Afya Foundation of America, Inc. 67,250 American Cancer Society, Inc. -

2020 IMPACT REPORT JCRC in 2021: Letter from the JEREMY BURTON STACEY BLOOM DEFENDING Executive Director & President Executive Director President DEMOCRACY Page 5

JCRC of Greater Boston Kraft Family Building | 126 High Street | Boston, MA 02110 617.457.8600 | jcrcboston.org [email protected] BostonJCRC BostonJCRC 2020 IMPACT REPORT JCRC IN 2021: Letter from the JEREMY BURTON STACEY BLOOM DEFENDING Executive Director & President Executive Director President DEMOCRACY page 5 FIGHTING FOR WE CANNOT YET SAY how our reality will be permanently altered in the wake of the coronavirus and In the pages of this report, you will read about the RACIAL JUSTICE page 7 the enduring crises we have faced this year. But there is one realization from this chapter of the resolve, steadfastness, and care that drove JCRC’s story we’re living through: JCRC’s commitment to fulfilling its mission remains constant. When the work this year. Together, we endeavored to achieve COMBATING pandemic hit, our response was deeply rooted in our understanding of JCRC’s core purpose. JCRC’s vision of a Greater Boston where the policy ANTISEMITISM Our work has proven essential to Boston’s Jewish community time and time again. Throughout priorities of the Jewish community are implemented, & HATRED page 9 the global health crisis and economic downturn, JCRC helped Jewish agencies and local non- and Jewish social service agencies are well-funded. Thank you to every JCRC partner, donor, volunteer, profits secure critical federal, state and local funding to address immediate needs. We combatted and leader who worked with us this year. WORKING FOR rising COVID-related food insecurity, homelessness, and economic devastation. And during the IMMIGRANT simultaneous resurgence of the movement for racial justice, JCRC galvanized the Jewish community Writing this in February 2021, we can’t tell you what JUSTICE page 11 of our region to stand with our partners in the Black community. -

J Street 2020 Election Survey Topline Results 110320.Docx

J Street October 28-November 3, 2020 National Jewish Voters Survey 800 Jewish Voters Q.2 Are you currently registered to vote? Total Yes.....................................................................................100 No.........................................................................................- Not sure................................................................................- Q.4 (PRE-ELECTION DAY) What are the chances of your voting in the upcoming general election for President, U.S. Congress, and other offices - have you already voted, are you almost certain to vote, will you probably vote, are the chances fifty-fifty, or don't you think you will vote? (ELECTION DAY) As you may know, there was an election today for President of the United States, Congress, and other offices. Many people weren't able to vote. How about you? Were you able to vote or for some reason were you unable to vote? Total Already voted/Voted...........................................................100 Almost certain.......................................................................- Probably...............................................................................- Fifty-fifty................................................................................- Will not vote/Did not vote......................................................- Q.6 What is your present religion, if any? Total Jewish (Judaism)................................................................86 Atheist..................................................................................6 -

Public Memorial for Victims of Pittsburgh Synagogue Shooting

Editorials ..................................... 4A Op-Ed .......................................... 5A Calendar ...................................... 6A Scene Around ............................. 9A Synagogue Directory ................ 11A News Briefs ............................... 13A WWW.HERITAGEFL.COM YEAR 44, NO. 11 NOVEMBER 15, 2019 17 CHESHVAN, 5780 ORLANDO, FLORIDA SINGLE COPY 75¢ Michael Bloomberg for president? By Ben Sales NEW YORK (JTA)—Mi- chael Bloomberg, the former New York City mayor and billionaire media mogul, ap- pears to be preparing to run for president. Bloomberg, 77, flirted with presidential runs in past elec- tion cycles before declining to run. As recently as March, he ruled out a presidential campaign this year, writing that he was “clear-eyed about the difficulty of winning the Democratic nomination in such a crowded field.” Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf Joins in mourning after the mass shooting of Jewish worshippers in the Tree of Life*Or But now he is registering Michael Bloomberg L’Simcha Synagogue in the Squirrel Hill neighborhood of Pittsburgh. to run in the Democratic pri- mary in Alabama, whose filing the race may draw votes away deadline is Friday, accord- from former Vice President ing to The New York Times. Joe Biden, another centrist. Public memorial for victims of Although the filing does not He is the second billionaire mean that Bloomberg would to enter the Democratic race definitely run, he has called a after Tom Steyer. Pittsburgh synagogue shooting number of senior Democratic Last year, ahead of the mid- leaders to tell them he is con- term elections, Bloomberg By Marcy Oster Cindy Snyder of the Center for Victims and recite with her the Birkat Hagomel sidering a campaign.