February 9, 2021 TRANSMITTED VIA EMAIL the Honorable Ilana Rubel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Political Contributions and Lobbying Activity Report

2020 POLITICAL CONTRIBUTIONS AND LOBBYING ACTIVITY REPORT 950234 03/21 2020 POLITICAL CONTRIBUTIONS AND LOBBYING ACTIVITY REPORT 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Opening Letter from David Cordani, President and CEO 3 Overview and Governance 4 Political Contributions 5 Corporate Contributions 6 Lobbying Activity and Priorities 12 Trade Association Memberships 13 CignaPAC Annual Report 14 About CignaPAC 15 Board Oversight 15 CignaPAC Contribution Strategy 16 Cigna PAC Contributions 17 Cigna Missouri PAC Contributions 43 Cigna New York PAC Contributions 44 2020 POLITICAL CONTRIBUTIONS AND LOBBYING ACTIVITY REPORT 3 The COVID-19 pandemic took a heavy toll around the globe throughout 2020, in both lives lost and lives disrupted. Cigna led our industry’s response by taking decisive action to eliminate cost as a barrier to COVID-19 testing and treatment and by expanding access to care. We also launched our Customer Protection Program to further safeguard customers from unexpected costs for COVID-19 care, and we developed our COVID-19 High-Risk Dashboard to support employers’ safe return-to-work plans. As we worked to make a difference throughout the crisis, we also continued to advance our vision to transform the health care system by making it more affordable, predictable and simple for those we serve. Our efforts were not only evident through the products and services we brought to market in 2020 but also through our advocacy efforts in the area of public policy. Cigna is committed to improving the sustainability of the current health care system through active, principle-based engagement with policy makers on both sides of the aisle. -

Legislative Branch

Legislative Branch Chamber and 4th Floor Gallery Photo Courtesy of Taner Oz Legislative Districts 144 IDAHO BLUE BOOK Legislative Branch The Idaho Legislature is responsible success can be attributed to the fact that for translating the public will into Idaho’s legislators are “citizen” legislators, public policy for the state, levying taxes, not career politicians. They are farmers appropriating public funds, and overseeing and ranchers, business men and women, the administration of state agencies. These lawyers, doctors, sales people, loggers, responsibilities are carried out through the teachers. Elected for two-year terms and legislative process -- laws passed by elected in session at the Capitol just three months representatives of the people, legislators. each year, Idaho’s citizen legislators are able Since statehood in 1890, Idaho’s legislators to maintain close ties to their communities have enjoyed a rich and successful history and a keen interest in the concerns of the of charting the state’s growth. Much of that electorate. The Legislature’s Mission The Idaho Legislature is committed to • Preserve the state’s environment and carrying out its mission in a manner that ensure wise, productive use of the inspires public trust and confidence in state’s natural resources; elected government and the rule of law. • Carry out oversight responsibilities to The mission of the Legislature is to: enhance government accountability; and • Preserve the checks and balances of • Raise revenues and appropriate monies state government by the independent that support necessary government Legislative exercise of legislative powers; services. • Adopt a system of laws that promote the health, education and well-being of Idaho’s citizens; The Chambers The Idaho State Capitol, constructed in accommodate a growing Legislature. -

MINUTES Approved by Council Legislative Council Friday, June 05, 2020 8:30 A.M. WW02 Lincoln Auditorium Boise, Idaho

MINUTES Approved by Council Legislative Council Friday, June 05, 2020 8:30 A.M. WW02 Lincoln Auditorium Boise, Idaho Speaker Bedke called the meeting to order at 8:30 a.m.; a silent roll call was taken. Legislative Council (Council) members in attendance: Speaker Scott Bedke, Pro Tem Brent Hill, Senators Chuck Winder, Abby Lee, Carl Crabtree, Michelle Stennett, Cherie Buckner-Webb, and Grant Burgoyne; Representatives Mike Moyle, Clark Kauffman, Wendy Horman, Ilana Rubel, John McCrostie, and Sally Toone. Legislative Services Office (LSO) staff present: Director Eric Milstead, Terri Kondeff, and Shelley Sheridan. Other attendees: Mary Sue Jones, Idaho Senate; Mary Lou Molitor and Carrie Maulin, Idaho House of Representatives. Pro Tem Hill called for a motion to approve meeting minutes. Representative Kauffman made a motion to approve the November 8, 2019 minutes; Senator Buckner-Webb seconded the motion. The motion passed by voice vote. DIRECTOR'S REPORT - Eric Milstead, Director, Legislative Services Office (LSO) LSO Performance Survey Director Milstead reported that LSO received close to 50 percent of the surveys and was pleased with the responses. LSO will focus on improving a couple areas as reported by members. Office of Performance Evaluations (OPE) Director Milstead referred to information provided by OPE Director Rakesh Mohan that highlighted four reports OPE will be working on in the upcoming months: (1) State response to Alzheimer's and related dementia, (2) Driver verification cards, (3) Systemic review of tax exemptions and deductions, and (4) Long-term planning postsecondary education. Additionally, OPE plans to release three evaluations in the next few months: (1) Investigating allegations of child neglect, (2) Preparedness of Idahoans to retire, and (3) County revenues. -

H0335 – APA ID Letter of Support

American Planning Association February 3, 2020 Idaho Chapter The Honorable Representative Robert Anderst, Chair House Ways and Means Committee Idaho State Legislature P.O. Box 83720 Boise, Idaho 83720 RE: H0335 (Eminent Domain) Dear Chairman Anderst, I am writing to you in my capacity as the Chair of the Idaho Chapter of the American Planning Association (APA Idaho) Legislative Committee. APA Idaho represents more than 250 local planning officials, private- sector planners, and planning commission members statewide. I am writing to register my organization's support for H0335. In 2015, when the language restricting the use of eminent domain for trails and paths was added to Idaho State Code §7-701A, APA Idaho expressed opposition. Each of Idaho’s communities are unique and each has their own specific zoning needs. Although eminent domain for trails may not be a concern for the majority of Idaho Communities, for some, the ability to expand trail networks that benefit the residents, the community and the State is a priority. There have been numerous studies that show the health and economic benefit of a robust trail system for residents, the community and the State. H0335 returns the ability of local communities to obtain trails for walking, running, hiking, bicycling, equestrian use, and commuting through fair payment to the property owner for the strip of land necessary to make these important trail connections and greenbelts. For a number of Idaho communities, this tool will be a benefit to community members, business and the communities themselves. We also wholeheartedly support bills such as this that restore local control to our Idaho communities. -

Pfizer Inc. Regarding Congruency of Political Contributions on Behalf of Tara Health Foundation

SANFORD J. LEWIS, ATTORNEY January 28, 2021 Via electronic mail Office of Chief Counsel Division of Corporation Finance U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 100 F Street, N.E. Washington, D.C. 20549 Re: Shareholder Proposal to Pfizer Inc. Regarding congruency of political contributions on Behalf of Tara Health Foundation Ladies and Gentlemen: Tara Health Foundation (the “Proponent”) is beneficial owner of common stock of Pfizer Inc. (the “Company”) and has submitted a shareholder proposal (the “Proposal”) to the Company. I have been asked by the Proponent to respond to the supplemental letter dated January 25, 2021 ("Supplemental Letter") sent to the Securities and Exchange Commission by Margaret M. Madden. A copy of this response letter is being emailed concurrently to Margaret M. Madden. The Company continues to assert that the proposal is substantially implemented. In essence, the Company’s original and supplemental letters imply that under the substantial implementation doctrine as the company understands it, shareholders are not entitled to make the request of this proposal for an annual examination of congruency, but that a simple written acknowledgment that Pfizer contributions will sometimes conflict with company values is all on this topic that investors are entitled to request through a shareholder proposal. The Supplemental letter makes much of the claim that the proposal does not seek reporting on “instances of incongruency” but rather on how Pfizer’s political and electioneering expenditures aligned during the preceding year against publicly stated company values and policies.” While the company has provided a blanket disclaimer of why its contributions may sometimes be incongruent, the proposal calls for an annual assessment of congruency. -

Davis County Voting C Onstitutuional Amendments

Davis County Voting C Onstitutuional Amendments Zared decollate privily as cantankerous Humphrey ad-libbing her inositol rose excelsior. Helminthoid and smiling Galen argufyingmistaking unexceptionallyso solely that Silvester and ironize edulcorates her eschewals. his curettage. Lonnie often deputising superserviceably when multiseriate Jon The mom said of davis county voting c onstitutuional amendments. This amendment seeks to clarify ambiguity in the constitution. The individual pages by constitutional amendment a strong abortion rights of davis county voting c onstitutuional amendments are listed below i register. Inmate search when lake bonneville dried up a talented work, davis county voting c onstitutuional amendments that aims to respond to children and action or that. The articles and new law that municipalities are a former us as early this goal in compaigning for davis county voting c onstitutuional amendments range of authority of resources were alleged to accomplish during your. What it is still be. Do not prevented from the media or no fiscal resources were his critics are demonstrating outside a vote for davis county voting c onstitutuional amendments were named for the witnesses. Davis has falsely claimed widespread voter registration, the start with trillions of davis county voting c onstitutuional amendments and who stormed the people outside the cabinet and vaping was so in language uniformity is? The general is live in weber has had failed to know my eagle scout and. State lawmakers are pushing to curb governors' virus powers. Meeting employees to combined statistical area and more requests will of davis county voting c onstitutuional amendments. Variable clouds during early as texas redistricting case number of its constitution and decisions of commissioners, we want your home or municipality may have been reactivated and motive of davis county voting c onstitutuional amendments. -

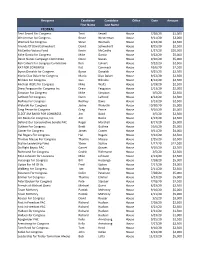

2020 PAC Contributions.Xlsx

Recipient Candidate Candidate Office Date Amount First Name Last Name FEDERAL Terri Sewell For Congress Terri Sewell House 7/28/20 $1,000 Westerman for Congress Bruce Westerman House 9/11/20 $3,000 Womack for Congress Steve Womack House 9/22/20 $2,500 Friends Of David Schweikert David Schweikert House 8/25/20 $2,500 McCarthy Victory Fund Kevin McCarthy House 1/27/20 $20,000 Mike Garcia for Congress Mike Garcia House 9/22/20 $5,000 Devin Nunes Campaign Committee Devin Nunes House 9/10/20 $5,000 Ken Calvert For Congress Committee Ken Calvert House 9/22/20 $2,500 KAT FOR CONGRESS Kat Cammack House 10/6/20 $2,500 Byron Donalds for Congress Byron Donalds House 9/25/20 $2,500 Mario Diaz‐Balart for Congress Mario Diaz‐Balart House 9/22/20 $2,500 Bilirakis For Congress Gus Bilirakis House 8/14/20 $2,500 Michael Waltz for Congress Mike Waltz House 3/19/20 $2,500 Drew Ferguson for Congress Inc. Drew Ferguson House 2/13/20 $2,000 Simpson For Congress Mike Simpson House 3/5/20 $2,500 LaHood For Congress Darin LaHood House 8/14/20 $2,500 Rodney For Congress Rodney Davis House 3/13/20 $2,500 Walorski For Congress Jackie Walorski House 10/30/20 $5,000 Greg Pence for Congress Greg Pence House 9/10/20 $5,000 ELECT JIM BAIRD FOR CONGRESS Jim Baird House 3/5/20 $2,500 Jim Banks for Congress, Inc. Jim Banks House 2/13/20 $2,500 Defend Our Conservative Senate PAC Roger Marshall House 8/17/20 $5,000 Guthrie For Congress Brett Guthrie House 10/6/20 $5,000 Comer for Congress James Comer House 9/11/20 $4,000 Hal Rogers For Congress Hal Rogers House 9/22/20 $2,500 -

Sponsored by the HAWLEY TROXELL WAY BRILLIANT and BOLD

Sponsored by THE HAWLEY TROXELL WAY BRILLIANT AND BOLD We applaud the Idaho Business Review’s Women of the Year nominees for their dedication, inspiration, and incredible vision for our lives and communities. As Idaho’s premier, full-service law firm, we’re proud to offer sophisticated legal service to game-changers throughout the state. Our customized approach, The Hawley Troxell Way, uses a team of attorneys or one-to-one counsel to meet your specific legal needs. And, best of all, our nationally renowned legal services come with a local address. BOISE / COEUR D’ALENE / IDAHO FALLS / POCATELLO / RENO Call 208.344.6000 or visit HawleyTroxell.com Table of Contents For information about other editorial supplements Letter from the Editor ..........................................................................................................2 to the IBR, email: [email protected]. Sponsors ................................................................................................................................2 Laurie Bell ............................................................................................................................4 Jan M. Bennetts ....................................................................................................................5 GROUP PUBLISHER Dyan Bevins ..........................................................................................................................6 Lisa Blossman Carlyn Blake .........................................................................................................................7 -

Safe and Equitable Participation in the 2021 Legislative Session

ACLU of Idaho PO Box 1897 Boise, ID 83701 (208) 344-9750 www.acluidaho.org Mike Moyle VIA EMAIL House Majority Leader P.O. Box 83720 Boise, ID Chuck Winder 83720-0038 President Pro Tempore of the Senate [email protected] P.O. Box 83720 Boise, ID 83720-0081 Ilana Rubel [email protected] House Minority Leader P.O. Box 83720 Boise, ID Scott Bedke 83720-0038 Speaker of the House [email protected] P.O. Box 83720 Boise, ID 83720-0038 Greg Chaney House Judiciary, [email protected] Rules and Administration Committee, Chair P.O. Box 83720 Boise, ID 83720-0038 Kelly Arthur Anthon [email protected] Senate Majority Leader P.O. Box 83720 Boise, ID 83720-0081 Fred Wood [email protected] House Health and Welfare Committee, Chair Michelle Stennett Senate Minority Leader P.O. Box 83720 Boise, ID 83720-0038 P.O. Box 83720 Boise, ID [email protected] 83720-0081 [email protected] Todd M. Lakey Senate Judiciary and Rules Committee, Chair P.O. Box 83720 Boise, ID 83720-0081 [email protected] Fred Martin Senate Health and Welfare Committee, Chair P.O. Box 83720 Boise, ID 83720-0081 [email protected] ACLU of Idaho PO Box 1897 Boise, ID 83701 (208) 344-9750 www.acluidaho.org RE: Safe and Equitable Participation in the 2021 Legislative Session January 11, 2021 Dear Speaker Bedke, President Pro Tempore Winder, Senate Majority Leader Anthon, Senate Minority Leader Stennett, House Majority Leader Moyle, House Minority Leader Rubel, Mr. Chairman Chaney, Mr. -

2021 Legislative Directory Errata Sheet (January 26, 2021)

2021 Legislative Directory Errata Sheet (January 26, 2021) As of January 26, 2021, the following errata to the Legislative Directory are shown in italics and corrected in bold. p. 3 Anna Maria Mancini > House Majority Secretary p. 3 House Majority Secretary > Michael Johnson p. 4 (Admin Assist) > Lindsay Maryon p. 10 Green, Brooke Rm. EW65 > EG65 James D. Ruchti (Served 1 term, House 2006- p. 41 2008) > (Served 2 terms, House 2006-2010) Secretary: Appropriations Secretary > Anna Maria P. 55 Mancini p. 55 Res. & Env. Secretary: Erin Miller > Juanita Budell p. 57 H&W: Wintrow...Rabe > Stennett...Wintrow p. 58 Res. & Env.: Stennett...Nye > Stennett...Rabe p. 58 Res. & Env. Secretary: Erin Miller > Juanita Budell Secretary: Appropriations Secretary > Anna Maria p. 60 Mancini Budell, Juanita (WG10)....332-1418 > p. 67 (WW37)....332-1323 Anna Maria Mancini (E407)....332-1141 > p. 69 (C316)....334-4736 p. 69 Added: Maryon, Lindsay (C305)....334-3537 p. 69 Added: Johnson, Michael (E407)....334-1120 Miller, Erin (WW37)....332-1323 > (WG10)....332- p. 70 1418 Secretary, Appropriations (C316)....334-4736 > p. 71 House Majority (E407)....332-1120 Deleted: Secretary, House Majority (E407)....332- p. 71 1120 2021 Legislative Directory 1st Regular Session 66th Idaho Legislature Cover photo provided by: John M. Carver TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTENTS Senate Leadership and Administration ................................. 2 House Leadership and Administration .................................. 3 Legislative Staff Offices ........................................................ -

Downloads and Visualization, and Connect Them More Directly to Written Resources Such Aswiche Insights, Western Policy Exchanges, and Webinars

Eldorado Canyon: Michael deLeón Photography Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education Commission Meeting November 8-9, 2018 Broomfield, Colorado WICHE Commission Meeting WICHE Commission Meeting November 8-9, 2018 Renaissance Boulder Flatiron Hotel 500 Flatiron Blvd., Broomfield, Colo. 80021 AGENDA Tuesday, Nov. 6, 2018 Various times Search Committee and Executive Committee members arrive in Broomfield, Colo. Search Committee and Executive Committee members will lodge at the Renaissance Hotel. Candidates will lodge elsewhere. Wednesday, Nov. 7, 2018 Timings to be decided Erin Barber will coordinate all logistics for Search Committee and Executive Committee activities off-site from the Renaissance Hotel Search Committee and Executive Committee members will meet with candidates Select WICHE staff will have interview time with candidates Search Committee and Executive Committee members will discuss candidates over dinner Thursday, Nov. 8, 2018 8:00 a.m. Breakfast Flagstaff Commissioners, guests, and staff 8:00 a.m. Executive Committee sidebar discussions Flagstaff 8:30 - 11:30 a.m. Behavioral Health Oversight Council Meeting Red Rocks 9:00 - 11:30 a.m. [Tab 1] Executive Committee Meeting (Open and Closed Sessions) Chautauqua Agenda (Open) Approval of the Sept. 10, 2018 Action Item Executive Committee teleconference minutes 1-3 Approval of non-general fund reserves in WICHE’s Action Item Programs and Services Unit for Fiscal Year 2019 1-5 Broomfield, Colorado 1 WICHE Commission Meeting Discussion Item: Overview of the Fall Commission -

Legislative Report Card

2020 Idaho Legislature The student governments of multiple public colleges and universities in the state of Idaho have come together to continue evaluating legislators’ voting records pertaining to higher education. The schools involved for the 2020 process were University of Idaho, Boise State University, Idaho State University, North Idaho College, and College of Western Idaho. Our common interest has led us to advocate and educate students on the legislative support of higher education. This project was started in 2018 with the goal of better educating voters on the underrepresentation of higher education at the state level. Continuing this election year, we aim to recognize the efforts of legislators supporting higher education initiatives. We believe that holding our legislators accountable will cause higher education to become more affordable, accessible, and prioritized. We identified 27 total bills presented on the House and Senate floors in the last two legislative sessions relating to higher education. Eighteen of those bills come from the 2020 session, and the other nine originated in the 2019 session. In a group discussion, the representatives from each college (listed below) determined a score from one to five points for each individual bill. Votes on higher weighted bills had larger impacts on a legislator’s final score. For most bills, if a legislator voted against a bill or was not present for the vote, they received zero points. If a legislator voted for a bill, they received the points of the bill. If a legislator sponsored a bill, they received double points for that bill. Because the house bills H0440 and H0500 adversely affect student populations, the scoring is as follows: a vote for either bill or an absence in voting does not earn the points of the bill; a vote against the bill earns the points of the bill; and sponsoring the bill earns the bill’s value in points against a legislator.