A Look at Films Funded by the Arkansas Humanities Council

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

Little Rock, AR (United States) FM Radio Travel DX

Little Rock, AR (United States) FM Radio Travel DX Log Updated 4/29/2019 Click here to view corresponding RDS/HD Radio screenshots from this log http://fmradiodx.wordpress.com/ Freq Calls City of License State Country Date Time Prop Miles ERP HD RDS Audio Information 88.3 KABF Little Rock AR USA 4/24/2019 6:36 PM Tr 6 91,000 variety 89.1 KUAR Little Rock AR USA 4/24/2019 6:37 PM Tr 6 63,000 HD RDS public radio 90.1 KLRO Hot Springs AR USA 4/24/2019 6:38 PM Tr 42 38,000 RDS "K-Love" - ccm 90.5 KLRE-FM Little Rock AR USA 4/24/2019 6:39 PM Tr 6 40,000 HD classical 90.9 KLLN Newark AR USA 4/24/2019 8:17 PM Tr 86 4,000 religious, car radio in Little Rock, AR 91.1 KANX Sheridan AR USA 4/24/2019 6:40 PM Tr 32 40,000 "AFR" - religious 91.3 KUCA Conway AR USA 4/24/2019 8:18 PM Tr 21 5,000 "The Bear" - school, car radio in Little Rock, AR 91.5 KALR Hot Springs AR USA 4/24/2019 8:20 PM Tr 36 4,500 ccm, car radio in Little Rock, AR 91.7 KBDO Des Arc AR USA 4/24/2019 6:40 PM Tr 41 56,000 "AFR" - religious 92.1 KHPQ Clinton AR USA 4/24/2019 8:22 PM Tr 62 10,000 RDS "Hot Country 92.1 KHPQ" - country, RDS hit, car radio in Little Rock, AR 92.3 KIPR Pine Bluff AR USA 4/24/2019 6:41 PM Tr 29 100,000 RDS "Power 9-2-3 Jamz" - urban 92.7 KASR Vilonia AR USA 4/24/2019 7:28 PM Tr 28 25,000 sports 92.9 KVRE Hot Springs Village AR USA 4/24/2019 7:20 PM Tr 39 25,000 "92-9 KVRE The Village" - standards 93.1 KZLE Batesville AR USA 4/25/2019 11:47 AM Tr 88 99,000 "93 KZLE" - rock, car radio in Little Rock, AR 93.3 KKSP Bryant AR USA 4/24/2019 6:42 PM Tr 4 22,000 RDS -

1909-11 American Tobacco Company T206 White Border Baseball

The Trading Card Database https://www.tradingcarddb.com 1909-11 American Tobacco Company T206 White Border Baseball NNO Ed Abbaticchio NNO John Butler NNO Mike Donlin NNO Clark Griffith NNO Ed Abbaticchio NNO Bobby Byrne NNO Mike Donlin NNO Moose Grimshaw NNO Fred Abbott NNO Howie Camnitz NNO Mike Donlin NNO Bob Groom NNO Bill Abstein NNO Howie Camnitz NNO Jiggs Donahue NNO Tom Guiheen NNO Doc Adkins NNO Howie Camnitz NNO Wild Bill Donovan NNO Ed Hahn NNO Whitey Alperman NNO Billy Campbell NNO Wild Bill Donovan NNO Bob Hall NNO Red Ames NNO Scoops Carey NNO Red Dooin NNO Bill Hallman NNO Red Ames NNO Charley Carr NNO Mickey Doolan NNO Jack Hannifin UER NNO Red Ames NNO Bill Carrigan NNO Mickey Doolan NNO Bill Hart NNO John Anderson NNO Doc Casey NNO Mickey Doolan NNO Jimmy Hart NNO Frank Arellanes NNO Peter Cassidy NNO Gus Dorner NNO Topsy Hartsel NNO Harry Armbruster NNO Frank Chance NNO Patsy Dougherty NNO Jack Hayden NNO Harry Arndt NNO Frank Chance NNO Patsy Dougherty NNO J. Ross Helm NNO Jake Atz NNO Frank Chance NNO Tom Downey NNO Charlie Hemphill NNO Home Run Baker NNO Bill Chappelle NNO Tom Downey NNO Buck Herzog NNO Neal Ball NNO Chappie Charles NNO Jerry Downs NNO Buck Herzog NNO Neal Ball NNO Hal Chase NNO Joe Doyle NNO Gordon Hickman NNO Jap Barbeau NNO Hal Chase NNO Joe Doyle NNO Bill Hinchman NNO Cy Barger NNO Hal Chase NNO Larry Doyle NNO Harry Hinchman NNO Jack Barry NNO Hal Chase NNO Larry Doyle NNO Dick Hoblitzell NNO Shad Barry NNO Hal Chase NNO Larry Doyle NNO Danny Hoffman NNO Jack Bastian NNO Jack Chesbro NNO Jean Dubuc NNO Izzy Hoffman NNO Emil Batch NNO Eddie Cicotte NNO Hugh Duffy NNO Solly Hofman NNO Johnny Bates NNO Bill Clancy NNO Jack Dunn NNO Buck Hooker NNO Harry Bay NNO Josh Clarke UER NNO Joe Dunn NNO Del Howard NNO Ginger Beaumont NNO Fred Clarke NNO Bull Durham NNO Ernie Howard NNO Fred Beck NNO Fred Clarke NNO Jimmy Dygert NNO Harry Howell NNO Beals Becker NNO J. -

Road Safety Audit Hyannis – Route 28 at Bearses Way Meeting Location: Growth Management Dept

ROAD SAFETY AUDIT Falmouth Road (Route 28)/Bearses Way Town of Barnstable May 2009 Prepared for: Massachusetts Highway Department Prepared by: Howard/Stein-Hudson Associates 38 Chauncy Street Boston, MA 02111 Road Safety Audit—Falmouth Road (Route 28)/Bearses Way, Barnstable Prepared by Howard/Stein-Hudson Associates, Inc. Table of Contents Project Data .................................................................................................................................1 Background..................................................................................................................................1 Project Location Description......................................................................................................2 Road Safety Audit Observations................................................................................................4 Safety Issue #1. Access Control ....................................................................................................8 Safety Issue #2. Lane Configuration .............................................................................................9 Safety Issue #3. Pavement Markings...........................................................................................10 Safety Issue #4. Pedestrian Accommodations.............................................................................10 Safety Issue #5. Bicycle Accommodations .................................................................................11 Safety Issue #6. Bus Accommodations -

Yearbook 14 Nl

Brooklyn surprises in 1914 National League replay Dodgers edge Cardinals by two games in hard-fought race 2 1914 National League Replay Table of Contents Final Standings and Leaders 3 Introduction 4-6 1914 NL pennant race recap 7-13 Inside the pennant race 14-19 NL All-Star team and NL standouts 15-28 Team totals 29 Leaders: batting, pitching, fielding 30-33 Individual batting, pitching, fielding 34-42 Pinch-hitting 43-45 Batting highlights and notes 46-54 Pitching highlights and notes 55-60 Pitchers records v. opponents 62-63 Fielding highlights 64-66 Injuries, ejections 67 Selected box scores 68-75 Scores, by month 76-87 3 1914 National League Final Standings and Leaders Replay Results Real Life Results W-L Pct. GB W-L Pct. GB Brooklyn Dodgers 86-68 .556 -- Boston Braves 94-59 .614 -- St. Louis Cardinals 84-70 .545 2 New York Giants 84-70 .545 10 ½ Boston Braves 81-73 .526 5 St. Louis Cardinals 81-72 .529 15 ½ Pittsburgh Pirates 79-75 .513 7 Chicago Cubs 78-76 .506 16 ½ New York Giants 77-77 .500 9 Brooklyn Dodgers 75-79 .487 19 ½ Chicago Cubs 75-79 .487 11 Philadelphia Phillies 74-80 .480 20 ½ Philadelphia Phillies 71-83 .461 15 Pittsburgh Pirates 69-85 .448 25 ½ Cincinnati Reds 63-91 .409 23 Cincinnati Reds 60-94 .390 34 ½ Batting leaders Pitching leaders Batting average Joe Connolly, Bos .342 ERA Jeff Pfeffer, Bkn, 1.41 On base pct. Joe Connolly, Bos, .423 Wins Grover Cleveland Alexander, Phila, 25-13 Slugging pct. -

June, 1947 1/3/47 I Ice Skating Carnivals in Each Five Boroughs On

INDEX \ January - June, 1947 1/3/47 I Ice skating carnivals in each five boroughs on Sunday, Jan. 12 1/5/47 2 Year end report on Park's activities and progress made dur- ing 1946 1/9/47 3 Warning for skaters to observe safety signs before going on frozen ponds and lakes 1/17/47 4 Procedure for assigning lockers at golf club houses 1/22/47 5 First day of ice skating in neighborhood playgrounds 2/8/47 6 Skiing and coasting areas in parks of all five boroughs listed 3/10/47 7 Schedule for first set of borough-wide elimination boxing bouts 3/17/47 8 Second week of elimination bouts in Parks Boxing Tournement 3/24/47 9 Last two sets of Borough-wide boxing finals in preparation for City-wide Championships in Department of Parks annual Boxing Tournement. 3/26/47 10, Finalists in three divisions of Parks Basketball Tournament to take place on March 29 at Madison Square Garden 3/27/47 11 For advent of Easter, Arnold Constable to sponser Egg & I Rolling Contest in Central Park on April 5 3/29/47 12 Park Department announces opening of Annual Easter Flower Show in Greenhouse at Prospect Park on Palm Sunday 3/30/47 13 Semi-finals in junior boxing tournement sponsored by Gimbels on 3/31/47 in Queens 4/2/47 14 750 girls and boys enter Arnold Constable Egg & I Rolling Contest; further details regarding rules and prizes 4/6/47 15 Last set of City-wide semi-finals in Department of Parks Boxing Tournement sponsored by Gimbels to be held on April 7 at 8 p.m. -

My Replay Baseball Encyclopedia Fifth Edition- May 2014

My Replay Baseball Encyclopedia Fifth Edition- May 2014 A complete record of my full-season Replays of the 1908, 1952, 1956, 1960, 1966, 1967, 1975, and 1978 Major League seasons as well as the 1923 Negro National League season. This encyclopedia includes the following sections: • A list of no-hitters • A season-by season recap in the format of the Neft and Cohen Sports Encyclopedia- Baseball • Top ten single season performances in batting and pitching categories • Career top ten performances in batting and pitching categories • Complete career records for all batters • Complete career records for all pitchers Table of Contents Page 3 Introduction 4 No-hitter List 5 Neft and Cohen Sports Encyclopedia Baseball style season recaps 91 Single season record batting and pitching top tens 93 Career batting and pitching top tens 95 Batter Register 277 Pitcher Register Introduction My baseball board gaming history is a fairly typical one. I lusted after the various sports games advertised in the magazines until my mom finally relented and bought Strat-O-Matic Football for me in 1972. I got SOM’s baseball game a year later and I was hooked. I would get the new card set each year and attempt to play the in-progress season by moving the traded players around and turning ‘nameless player cards” into that year’s key rookies. I switched to APBA in the late ‘70’s because they started releasing some complete old season sets and the idea of playing with those really caught my fancy. Between then and the mid-nineties, I collected a lot of card sets. -

R Bemidji Ness, to Invite More Customers to Your Store

***************** * BIO GUARD MAY BE * PORT * LOST TO HIGH SCHOOL * WORLD'S SERIES FOR SALE—17 Buff Rock** chickens. * FOOTBALL ELEVEN * WAGERS IN BEMIDJI ***************** Cheap if taken at once; 2nd prize %m iHfcws There has been consider at county fair. Phone 621-W. dti Our Invitation to able betting on the outcome FOR SALE^-^Canoe in first class con of the world's series in Be dition. t B^Jc£ Baer. 5d£09 midji during the past few days. FOR SALE-^18^*acres Lake Shore Progressive Merchants land at $50 an acre^ Frank Lane. Today $100 was posted -^•^saeassnsr •* • NAVAL MILITIA ELEVEN against $95 a fraction there r. *; - dl09 * of in comparison that Phila We have asked you to join in a forward movement* for toefter busi MUST WORK TO WIN FOR SALE—No. 526. For Bemidji ness, to invite more customers to your store. -•'•' delphia would win the first mill men,"" 40-acre choice farm game. stead. Jim's Glover Home. NW, Our invitation is not only in Ijehalf of the live newspapers of-this The Bemidji naval militia football SW, Sec. 32, T. 148, R. 33. One city, but from every newspaper in North America. ' organization is rapidly being per ft**************** mile from Wright's Spur, one mile Just as you have been asked to join in— '" "'' fected and games will probably be from new school house, one mile PANAMA CANAL from Moville Lake; level, clay loam secured, beginning with next Sun SLIDE HALTS TRAFFIC land, easily cleared. Price only day. Grand Rapids, Thief River Panama, Oct. 5. — Lieutenant $15.00 per acre; $20.00 down, INTERNATIONAL Falls, Duluth, Crosby and the local HAROLD SWISHER Colonel Chester Harding the engineer $5.00 per month, six per cent in team headed by Jack O'Connor, have in charge of the Panama canal, has terest. -

Election Day — Documentary

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 7-2020 Election Day — Documentary John Thomas Tarpley University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the American Film Studies Commons, Film Production Commons, and the Journalism Studies Commons Citation Tarpley, J. T. (2020). Election Day — Documentary. Theses and Dissertations Retrieved from https://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/3830 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Election Day — Documentary A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism by John Thomas Tarpley Lyon College Bachelor of Arts in English, 2010 July 2020 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council _________________________________ Colleen Thurston, M.F.A. Thesis Director _________________________________ _________________________________ Niketa Reed, M.A. Frank Milo Scheide, Ph.D. Committee Member Committee Member ABSTRACT Election Day is a three-channel documentary chronicling the places, personalities, and tone of Little Rock, Arkansas, during its titular midterm Election Day in November 2018. Throughout the course of the day, the film branches across the city, capturing mini-narratives, bits of conversation, and tableau of civic activity in the public sphere. It is less concerned with the quantitative facts of the day as it is with conveying the transitory social expressions and moods of a modern, southern city on a uniquely American day. -

Judsonia Kensett Lake City Lake Village Lakeview Little Rock

KAOG Contemporary Christian* KPZK Urban Contemporary [Repeats: KIPR 92.3] 90.5 40000w 397ft DA Lake City 1250 2000/ 1200 DA-2 +American Family Association +Cltadel Communications Corp. KDXY Country™ 662-844-8888 fax: 662-842-6791 Sister to: KAAY, KARN, KARN-F, KIPR, KLAL, KURB 104.9 13500w 449ft PO Box 3206, Tupelo MS 38803 501-401-0200 fax: 501-401-0367 +Saga Communications, Inc. 107 Park Gate Dr, Tupelo MS 38801 700 Wellington Hills Rd, 72211 Sister to: KEGI, KJBX GM Marvin Sanders PD Rick Robertson GM/SM Richard Nickols PD Joe Booker 870-933-8800 fax: 870-933-0403 CE Joey Moody CE Dan Case 314 Union St, Jonesboro 72401 www.afr.net www.power923.com GM Trey Stafford SM Kevin Neathery Jonesboro Market Little Rock Market PD Christie Matthews CE Al Simpson KASU News /Classical /Jazz* www.thefox1049.com KTUV Spanish Jonesboro Arbitron 14.6 Shr 1300 AQH 91.9 100000W 688ft DA 1440 5000/240 DA-N Arkansas State University +Birach Broadcasting Corp. 870-972-3070 fax: 870-972-2997 Lake Village 877-426-1447 PO Box 2160, State University 72467 723 W Daisy L Gatson Bates Dr, 72202 104 Cooley St, Jonesboro 72467 KUUZ Religious Teaching* www.potencialatina.net GM Mike Doyle SM Todd Rutledge 95.9 20000w 302ft Little Rock Market PD Marty Scarbrough CE Eddy Arnold +Family Worship Center Church, Inc. www.kasu.org 225-768-3688 fax: 225-768-3729 KABF Variety* Jonesboro Market PO Box 262550, Baton Rouge LA 70826 88.3 100000W 776ft 8919 World Ministry Ave, Baton Rouge LA 70810 Arkansas Broadcasting Foundation KEGI Classic Hits GM/PD Ted Semper CE Tony Evans 501-372-6119 fax: 501-375-5965 100.5 38000w 558ft www.sonliferadio.org 2101 Main St Ste 200,72206 +Saga Communications, Inc. -

Cw Cw Cw Cw Cw Cw Cw

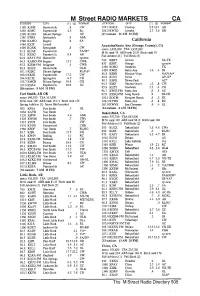

STATION CITY (1) (2) FORMAT STATION CITY (1) (2) FORMAT 1190 KJEM Bentonville .8 CW 105.1 KMJX Conway 9.3 12.1 AR 1250 KOFC Fayetteville 2.5 RL 106.3 KWTD Lonoke 2.3 3.6 RB 1290 KUOA Siloam Springs AC [27 stations 12 AM 15 FM] 1340 KBRS Springdale .4 AS& 1390 KAMO Rogers .8 SA California 1440 KKIP Lowell - Anaheim/Santa Ana (Orange County), CA 1590 KQXK Springdale .8 cw metro 1,935,200 TSA 1,935,200 FA/JZ* 91.3 KUAF Fayetteville M St. rank 19 ARB rank 20 /4 Birch rank 19 AR 92.1 KKEG Fayetteville 8.8 Fall Arbitron (1) Fall Birch (2) 92.9 KFAY-FM Huntsville cp-new RL-TK 94.3 KAMO-FM Rogers 15.1 CW& 740 KBRT Aval on 95.3 KJEM-FM Seligman .4 CW& 830 KSRT Orange cp-new 98.3 KOLZ Bentonville OL& 1190 KORG Anaheim TK 101.1 KLRC Siloam Springs RL/FA* 1480 KWIZ Santa Ana 1.6 .4 SS 103.9 KKIX Fayetteville 17.2 cw 88.5 KSBR Mission Viejo NA/VAe* 104.9 KCIZ Springdale 6.3 CH 88.9 KUCI Irvine AP-JZ* 105.7 KMCK Siloam Springs 10.9 CH 90.1 KBPK Buena Park AC* CW 107.9 KEZA Fayetteville 10.9 AC 94.3 K1KF Garden Grove 1.2 .8 [20 stations 9 AM 11FM] 95.9 KEZY Anaheim 1.3 .4 CH 96.7 KWIZ-FM Santa Ana .8 .5 AC Fort Smith, AR OK 97.9 KSKQ-FM Long Beach .9 SS-CH metro 190,100 TSA 313,500 103.1 KOCM Newport Beach .8 .2 EZ M St. -

Giants Badly Mauled and Fairly Humbled By

"Shot-to-Pieces" DEBÜT OF TIP TOPS Giants Badly Mauled and Fairly Humbled by MARKED BY VICTOIlï First Clash for a Fourth Straight Pennant Phillies in Their Seaton Twirls in Masterly Fashion and Shuts Out "Rube" Marquard Gets Pittsburgh Feds. Shock as Magee Lint Out Two Home Runs. GAME IS WON IN THE TENTH DOOIN AND HIS MEN UP TEN RU BUILD Two Bases on Balls and a Sing!« by Westerziel Does Trick. Clan McOraw in the Mean Ti 15.000 Watch Contest. Gets One Man Over the (Malt .. and That's All. Pitts .prll» Ths Brooklyn IS Tops made tebut hsr* J. '. ne. J day, and I uful 01 > Patera - -1' »ere Ph lads .'. 'i The Pittsburgh defeat**! v. York Giants, with Rubs Marquars lass .Full) Hfl . Bto k at th perseae -. the ! oat and Milton out t" '.'.-.,; w=»d to shine, w v. here TllllS BhafOT ordfl estai llshed by ,,.^ mauled and I in bit d b| mr "shot League ten:.. .». the : Phillies here to-day as t..m fleaton, the f<. mer itehssr of,. 09 was «1 .Phlllli b, who ...'.... with aim. Th' score wai ti«iti n«>t i,:.- i:¡fl4 and the itlaws 1. and io score ever told m "v\»n y. to i ws ' of a game. For in the best .'early the story -the I am Me '.he National Leai Brooklyn showed the! -« brief moment was well worth ail the strlf« he flashed in the lead, cast v4< champions he he . ti pit. hi a little gloom over the fans, but s ore what hi .well, the explains .