Criminal Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charging Language

1. TABLE OF CONTENTS Abduction ................................................................................................73 By Relative.........................................................................................415-420 See Kidnapping Abuse, Animal ...............................................................................................358-362,365-368 Abuse, Child ................................................................................................74-77 Abuse, Vulnerable Adult ...............................................................................78,79 Accessory After The Fact ..............................................................................38 Adultery ................................................................................................357 Aircraft Explosive............................................................................................455 Alcohol AWOL Machine.................................................................................19,20 Retail/Retail Dealer ............................................................................14-18 Tax ................................................................................................20-21 Intoxicated – Endanger ......................................................................19 Disturbance .......................................................................................19 Drinking – Prohibited Places .............................................................17-20 Minors – Citation Only -

Evidence in Criminal Proceedings Hearsay and Related Topics

Criminal Law EVIDENCE IN CRIMINAL PROCEEDINGS: HEARSAY AND RELATED TOPICS A Consultation Paper LAW COMMISSION CONSULTATION PAPER No 138 The Law Commission was set up by section 1 of the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law. The Law Commissioners are: The Honourable Mr Justice Brooke, Chairman Professor Andrew Burrows Miss Diana Faber Mr Charles Harpum Mr Stephen Silber, QC The Secretary of the Law Commission is Mr Michael Sayers and its offices are at Conquest House, 37-38 John Street, Theobalds Road, London WClN 2BQ. This Consultation Paper, completed for publication on 11 May 1995, is circulated for comment and criticism only. It does not represent the final views of the Law Commission. The Law Commission would be grateful for comments on this Consultation Paper before 31 October 1995. All correspondence should be addressed to: Ms C Hughes Law Commission Conquest House 37-38 John Street Theobalds Road London WClN 2BQ (Tel: 0171- 453 1232) (Fax: 0171- 453 1297) It may be helpful for the Law Commission, either in discussion with others concerned or in any subsequent recommendations, to be able to refer to and attribute comments submitted in response to this Consultation Paper. Any request to treat all, or part, of a response in confidence will, of course, be respected, but if no such request is made the Law Commission will assume that the response is not intended to be confidential. The Law Commission Consultation Paper No 138 Criminal Law EVIDENCE IN CRIMINAL PROCEEDINGS: HEARSAY AND RELATED TOPICS -

Imagereal Capture

Some Aspects of Theft of Computer Software by M. Dunning I. INTRODUCTION The purpose of this paper is to test the capability of New Zealand law to adequately deal with the impact that computers have on current notions of crimes relating to property. Has the criminal law kept pace with technology and continued to protect property interests or is our law flexible enough to be applied to new situations anyway? The increase of the moneyless society may mean a decrease in money motivated crimes of violence such as robbery, and an increase in white collar crime. Every aspect of life is being computerised-even our per sonality is on character files, with the attendant )ossibility of criminal breach of privacy. The problems confronted in this area are mostly definitional. While it may be easy to recognise morally opprobrious conduct, the object of such conduct may not be so easily categorised as criminal. A factor of this is a general lack of understanding of the computer process, so this would seem an appropriate place to begin the inquiry. II. THE COMPUTER Whiteside I identifies five key elements in a computer system. (1) Translation of data into a form readable by the computer, called input; and subject to manipulation by the introduction of false data. Remote terminals can be situated anywhere outside the cen tral processing unit (CPU), connected by (usually) telephone wires over which data may be transmitted, e.g. New Zealand banks on line to Databank. Outside users are given a site code number (identifying them) and an access code number (enabling entry to the CPU) which "plug" their remote terminal in. -

Public Law and Civil Liberties ISBN 978-1-137-54503-9.Indd

Copyrighted material – 9781137545039 Contents Preface . v Magna Carta (1215) . 1 The Bill of Rights (1688) . 2 The Act of Settlement (1700) . 5 Union with Scotland Act 1706 . 6 Official Secrets Act 1911 . 7 Parliament Acts 1911 and 1949 . 8 Official Secrets Act 1920 . 10 The Statute of Westminster 1931 . 11 Public Order Act 1936 . 12 Statutory Instruments Act 1946 . 13 Crown Proceedings Act 1947 . 14 Life Peerages Act 1958 . 16 Obscene Publications Act 1959 . 17 Parliamentary Commissioner Act 1967 . 19 European Communities Act 1972 . 24 Local Government Act 1972 . 26 Local Government Act 1974 . 30 House of Commons Disqualification Act 1975 . 36 Ministerial and Other Salaries Act 1975 . 38 Highways Act 1980 . 39 Senior Courts Act 1981 . 39 Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 . 45 Public Order Act 1986 . 82 Official Secrets Act 1989 . 90 Security Service Act 1989 . 96 Intelligence Services Act 1994 . 97 Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 . 100 Police Act 1996 . 104 Police Act 1997 . 106 Human Rights Act 1998 . 110 Scotland Act 1998 . 116 Northern Ireland Act 1998 . 121 House of Lords Act 1999 . 126 Freedom of Information Act 2000 . 126 Terrorism Act 2000 . 141 Criminal Justice and Police Act 2001 . 152 Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001 . 158 Police Reform Act 2002 . 159 Constitutional Reform Act 2005 . 179 Serious Organised Crime and Police Act 2005 . 187 Equality Act 2006 . 193 Terrorism Act 2006 . 196 Government of Wales Act 2006 . 204 Serious Crime Act 2007 . 209 UK Borders Act 2007 . 212 Parliamentary Standards Act 2009 . 213 Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010 . 218 European Union Act 2011 . -

Common Law Fraud Liability to Account for It to the Owner

FRAUD FACTS Issue 17 March 2014 (3rd edition) INFORMATION FOR ORGANISATIONS Fraud in Scotland Fraud does not respect boundaries. Fraudsters use the same tactics and deceptions, and cause the same harm throughout the UK. However, the way in which the crimes are defined, investigated and prosecuted can depend on whether the fraud took place in Scotland or England and Wales. Therefore it is important for Scottish and UK-wide businesses to understand the differences that exist. What is a ‘Scottish fraud’? Embezzlement Overview of enforcement Embezzlement is the felonious appropriation This factsheet focuses on criminal fraud. There are many interested parties involved in of property without the consent of the owner In Scotland criminal fraud is mainly dealt the detection, investigation and prosecution with under the common law and a number where the appropriation is by a person who of statutory offences. The main fraud offences has received a limited ownership of the of fraud in Scotland, including: in Scotland are: property, subject to restoration at a future • Police Service of Scotland time, or possession of property subject to • common law fraud liability to account for it to the owner. • Financial Conduct Authority • uttering There is an element of breach of trust in • Trading Standards • embezzlement embezzlement making it more serious than • Department for Work and Pensions • statutory frauds. simple theft. In most cases embezzlement involves the appropriation of money. • Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service. It is important to note that the Fraud Act 2006 does not apply in Scotland (apart from Statutory frauds s10(1) which increases the maximum In addition there are a wide range of statutory Investigating fraud custodial sentence for fraudulent trading to offences which are closely related to the 10 years). -

Crimes Act 2016

REPUBLIC OF NAURU Crimes Act 2016 ______________________________ Act No. 18 of 2016 ______________________________ TABLE OF PROVISIONS PART 1 – PRELIMINARY ....................................................................................................... 1 1 Short title .................................................................................................... 1 2 Commencement ......................................................................................... 1 3 Application ................................................................................................. 1 4 Codification ................................................................................................ 1 5 Standard geographical jurisdiction ............................................................. 2 6 Extraterritorial jurisdiction—ship or aircraft outside Nauru ......................... 2 7 Extraterritorial jurisdiction—transnational crime ......................................... 4 PART 2 – INTERPRETATION ................................................................................................ 6 8 Definitions .................................................................................................. 6 9 Definition of consent ................................................................................ 13 PART 3 – PRINCIPLES OF CRIMINAL RESPONSIBILITY ................................................. 14 DIVISION 3.1 – PURPOSE AND APPLICATION ................................................................. 14 10 Purpose -

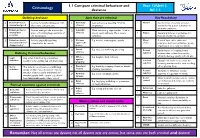

1.1 Compare Criminal Behaviour and Deviance

1.1 Compare criminal behaviour and Year 12/Unit 2. Criminology deviance AC 1.1 Defining deviance Acts that are criminal Key Vocabulary 1 Behaviour that is Such as heroically risking your own 1 Summary Less serious e.g. speeding. Tried by 1 Norms Specific rules or socially accepted unusual and good life to save someone else. offences magistrates. standards that govern behaviour in particular situations. 2 Behaviour that is Such as talking to the trees in the 2 Indictable More serious e.g. rape/murder. Tried in unusual and park, or hoarding huge quantities of offences crown court with jury. More severe 2 Values General principles or guidelines for eccentric old newspapers. sentences. how we should live our lives. 3 Behaviour that is Such as physically attacking 3 Violence E.g. murder, manslaughter, assault 3 Moral A set of basic rules, values and unusual and bad or someone for no reason. against the codes prinicples, held by an individual, group, disapproved of person organisation or society as a whole. 4 Sexual E.g. rape, sex trafficking, grooming. 4 Formal Punishments for breaking formal offences Defining Criminal behaviour sanction written rules or laws. Imposed by Offences official bodies e.g. courts, schools etc. Legal Any action forbidden by criminal law – 5 E.g. burglary, theft, robbery. 1 against definition 5 Informal Disapproval shown to a person for usually involves actus rea and mens rea property sanction breaking unwritten rules, such as telling 2 Social This includes consideration of differing 6 Fraud and E.g. frauds by company directors, benefit off or ignoring them. -

Crime and Punishment Affray

(crime) CRIME AND PUNISHMENT Affr ay Armed – riding and going Arson and maiming Barretr y (causing unnecessary legal actions) Burglary Forcible Detainer Felonies: buggery, abduction, tongue or eyes, stealing records, multiplication of gold or silver, unlawful hunting, bigamy Forcible entry Larceny Murder and homicide Offences by officer s Rape and attempted rape Riot Robbery Suicide Theft Treason Witchcraf t AFFRAY Hale gave the following definition of affray: 'if weapons drawn, or stroke given or offered, but words no affray: menace to kill or beat, no affr ay, but yet for safeguard of peace, constable may bring them before Justice'. It would thus appear that in order to commit an affray a weapon must be drawn, or a stroke given or offered. In the event of an affray, if it wer e considerable, a private person might stop the affray and deliver them to the constable. If a person hurt another dangerously, a private person might arrest the offender , and bring him to gaol or to the next Justice. A constable or Jus tice must suppress all affrays . Affr ays were misdemeanours, not punishable by death. Where were they pros ecuted and how punished? KING S BENCH AND ASS IZES A first glance through the KB and ASS I material(to be checked with the machine) does not reveal any cases of simple affr ay being prosecuted. This would not be surprising, since the offence was not of a suf ficiently serious nature in itself to come to these courts. The one exception I have found occurred in the Assizes for 1603 when three EC yeomen were indicted for assaulting a man at Bures. -

Criminal Law: Conspiracy to Defraud

CRIMINAL LAW: CONSPIRACY TO DEFRAUD LAW COMMISSION LAW COM No 228 The Law Commission (LAW COM. No. 228) CRIMINAL LAW: CONSPIRACY TO DEFRAUD Item 5 of the Fourth Programme of Law Reform: Criminal Law Laid before Parliament bj the Lord High Chancellor pursuant to sc :tion 3(2) of the Law Commissions Act 1965 Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 6 December 1994 LONDON: 11 HMSO E10.85 net The Law Commission was set up by section 1 of the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law. The Commissioners are: The Honourable Mr Justice Brooke, Chairman Professor Andrew Burrows Miss Diana Faber Mr Charles Harpum Mr Stephen Silber QC The Secretary of the Law Commission is Mr Michael Sayers and its offices are at Conquest House, 37-38 John Street, Theobalds Road, London, WClN 2BQ. 11 LAW COMMISSION CRIMINAL LAW: CONSPIRACY TO DEFRAUD CONTENTS Paragraph Page PART I: INTRODUCTION 1.1 1 A. Background to the report 1. Our work on conspiracy generally 1.2 1 2. Restrictions on charging conspiracy to defraud following the Criminal Law Act 1977 1.8 3 3. The Roskill Report 1.10 4 4. The statutory reversal of Ayres 1.11 4 5. Law Commission Working Paper No 104 1.12 5 6. Developments in the law after publication of Working Paper No 104 1.13 6 7. Our subsequent work on the project 1.14 6 B. A general review of dishonesty offences 1.16 7 C. Summary of our conclusions 1.20 9 D. -

Chapter 8 Criminal Conduct Offences

Chapter 8 Criminal conduct offences Page Index 1-8-1 Introduction 1-8-2 Chapter structure 1-8-2 Transitional guidance 1-8-2 Criminal conduct - section 42 – Armed Forces Act 2006 1-8-5 Violence offences 1-8-6 Common assault and battery - section 39 Criminal Justice Act 1988 1-8-6 Assault occasioning actual bodily harm - section 47 Offences against the Persons Act 1861 1-8-11 Possession in public place of offensive weapon - section 1 Prevention of Crime Act 1953 1-8-15 Possession in public place of point or blade - section 139 Criminal Justice Act 1988 1-8-17 Dishonesty offences 1-8-20 Theft - section 1 Theft Act 1968 1-8-20 Taking a motor vehicle or other conveyance without authority - section 12 Theft Act 1968 1-8-25 Making off without payment - section 3 Theft Act 1978 1-8-29 Abstraction of electricity - section 13 Theft Act 1968 1-8-31 Dishonestly obtaining electronic communications services – section 125 Communications Act 2003 1-8-32 Possession or supply of apparatus which may be used for obtaining an electronic communications service - section 126 Communications Act 2003 1-8-34 Fraud - section 1 Fraud Act 2006 1-8-37 Dishonestly obtaining services - section 11 Fraud Act 2006 1-8-41 Miscellaneous offences 1-8-44 Unlawful possession of a controlled drug - section 5 Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 1-8-44 Criminal damage - section 1 Criminal Damage Act 1971 1-8-47 Interference with vehicles - section 9 Criminal Attempts Act 1981 1-8-51 Road traffic offences 1-8-53 Careless and inconsiderate driving - section 3 Road Traffic Act 1988 1-8-53 Driving -

CHAPTER 10 General Offenses

CHAPTER 10 General Offenses Article I Offenses and Miscellaneous Provisions Sec. 10-1 Definitions generally Sec. 10-2 Legislative intent Sec. 10-3 Affirmative defenses Sec. 10-4 Penalty Sec. 10-5 Parental responsibility for acts of minor children Sec. 10-6 Attempts; aiding, abetting or advising Sec. 10-7 Accessory to crime Article II Property Sec. 10-21 Trespass Sec. 10-22 Interference with use of public property Sec. 10-23 Parking on private premises Sec. 10-24 Littering Article III Damage or Destruction Sec. 10-41 Public property generally Sec. 10-42 Criminal mischief Sec. 10-43 Posters Article IV Theft and Related Offenses Sec. 10-61 Theft generally Sec. 10-62 Bad checks Sec. 10-63 Theft of rental property Sec. 10-64 Joyriding Sec. 10-65 Shoplifting Sec. 10-66 Price switching Sec. 10-67 Theft by receiving Sec. 10-68 Questioning of person suspected of theft without liability Article V Public Health and Safety Sec. 10-81 Abandoned containers Sec. 10-82 Storage of flammable liquids in vehicles Sec. 10-83 Storage of construction materials Sec. 10-84 Contamination of water Sec. 10-85 Poisonous substances Sec. 10-86 Cruelty to animals Sec. 10-87 Hunting and feeding of wildlife prohibited Sec. 10-88 Fire bans Article VI Morals Sec. 10-101 Lewd conduct Sec. 10-102 Obscene conduct Sec. 10-103 Indecent books or demonstrations Article VII Public Peace Sec. 10-121 Disorderly conduct Sec. 10-122 Disrupting lawful assembly Sec. 10-123 Loitering Sec. 10-124 Unlawful assembly Sec. 10-125 Unlawful interference; educational institutions 10-1 Sec. -

Table of Common Charge Options for State Offences

TABLE OF COMMON CHARGE OPTIONS FOR STATE OFFENCES A PRACTITIONERS’ GUIDE FOR THE EAGP SCHEME The Public Defenders Last updated 8 March 2019 Users’ guide, notes and acknowledgements The purpose of this document and a disclaimer • This document has been prepared as a resource designed to assist lawyers, whether defence or prosecution, involved in negotiations under the Early Appropriate Guilty Plea legislation. • You should always undertake your own research into the particular offences and provisions which may be relevant to any case you are working on. This document is a guide only and should be treated as a starting point for your consideration of appropriate offences. • Further and importantly, this document refers to the current versions of offences, maximum penalties and standard non-parole periods. You should always refer to the version of the legislation applicable at the time of any alleged offence. Because changes to sexual assault offences are so recent, we have included the most recently repealed offences for your convenience. • Please ensure you are working from the latest version of this document available from the Public Defenders’ website. The date of the most recent update is on the title page. • Please bear in mind that this document does not include any Commonwealth offences. Commonwealth offences might be alternatives to, for example, child pornography, grooming and procuring, money laundering, terrorism and drug offences. • Whilst every effort has been made to ensure the correctness of information in this Table, please be reminded of the Disclaimer pertaining to all information on the website of Public Defenders, Department of Justice NSW at: https://www.justice.nsw.gov.au/Pages/copyright-disclaimer.aspx Acknowledgments This Table has been prepared by the Public Defenders with assistance and input from Legal Aid NSW and the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions NSW, initially as part of the Early Appropriate Guilty Plea Working Party 2018.