Finders Keepers”: Performing the Street, the Gallery and the Spaces In-Between

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anti-Trump Street Art Along the US-Mexico Border" (2019)

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Center for Advanced Research in Global CARGC Papers Communication (CARGC) 8-2019 Dreamers and Donald Trump: Anti-Trump Street Art Along the US- Mexico Border Julia Becker [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/cargc_papers Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Becker, Julia, "Dreamers and Donald Trump: Anti-Trump Street Art Along the US-Mexico Border" (2019). CARGC Papers. 11. https://repository.upenn.edu/cargc_papers/11 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/cargc_papers/11 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dreamers and Donald Trump: Anti-Trump Street Art Along the US-Mexico Border Description What tools are at hand for residents living on the US-Mexico border to respond to mainstream news and presidential-driven narratives about immigrants, immigration, and the border region? How do citizen activists living far from the border contend with President Trump’s promises to “build the wall,” enact immigration bans, and deport the millions of undocumented immigrants living in the United States? How do situated, highly localized pieces of street art engage with new media to become creative and internationally resonant sites of defiance? CARGC Paper 11, “Dreamers and Donald Trump: Anti-Trump Street Art Along the US-Mexico Border,” answers these questions through a textual analysis of street art in the border region. Drawing on her Undergraduate Honors Thesis and fieldwork she conducted at border sites in Texas, California, and Mexico in early 2018, former CARGC Undergraduate Fellow Julia Becker takes stock of the political climate in the US and Mexico, examines Donald Trump’s rhetoric about immigration, and analyzes how street art situated at the border becomes a medium of protest in response to that rhetoric. -

The Evolution of Graffiti Art

Journal of Conscious Evolution Volume 11 Article 1 Issue 11 Issue 11/ 2014 June 2018 From Primitive to Integral: The volutE ion of Graffiti Art White, Ashanti Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/cejournal Part of the Clinical Psychology Commons, Cognition and Perception Commons, Cognitive Psychology Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Liberal Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons, Social Psychology Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, Sociology of Religion Commons, and the Transpersonal Psychology Commons Recommended Citation White, Ashanti (2018) "From Primitive to Integral: The vE olution of Graffiti Art," Journal of Conscious Evolution: Vol. 11 : Iss. 11 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/cejournal/vol11/iss11/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Conscious Evolution by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. : From Primitive to Integral: The Evolution of Graffiti Art Journal of Conscious Evolution Issue 11, 2014 From Primitive to Integral: The Evolution of Graffiti Art Ashanti White California Institute of Integral Studies ABSTRACT Art is about expression. It is neither right nor wrong. It can be beautiful or distorted. It can be influenced by pain or pleasure. It can also be motivated for selfish or selfless reasons. It is expression. Arguably, no artistic movement encompasses this more than graffiti art. -

PIER 34 Something Possible Everywhere Something Possible

NYC 1983–84 NYC PIER 34 Something Possible Everywhere Something Possible PIER 34 Something Possible Everywhere NYC 1983–84 PIER 34 Something Possible Everywhere NYC 1983–84 Jane Bauman PIER 34 Mike Bidlo Something Possible Everywhere Paolo Buggiani NYC 1983–84 Keith Davis Steve Doughton John Fekner David Finn Jean Foos Luis Frangella Valeriy Gerlovin Judy Glantzman Peter Hujar Alain Jacquet Kim Jones Rob Jones Stephen Lack September 30–November 20 Marisela La Grave Opening reception: September 29, 7–9pm Liz-N-Val Curated by Jonathan Weinberg Bill Mutter Featuring photographs by Andreas Sterzing Michael Ottersen Organized by the Hunter College Art Galleries Rick Prol Dirk Rowntree Russell Sharon Kiki Smith Huck Snyder 205 Hudson Street Andreas Sterzing New York, New York Betty Tompkins Hours: Wednesday–Sunday, 1–6pm Peter White David Wojnarowicz Teres Wylder Rhonda Zwillinger Andreas Sterzing, Pier 34 & Pier 32, View from Hudson River, 1983 FOREWORD This exhibition catalogue celebrates the moment, thirty-three This exhibition would not have been made possible without years ago, when a group of artists trespassed on a city-owned the generous support provided by Carol and Arthur Goldberg, Joan building on Pier 34 and turned it into an illicit museum and and Charles Lazarus, Dorothy Lichtenstein, and an anonymous incubator for new art. It is particularly fitting that the 205 donor. Furthermore, we could not have realized the show without Hudson Gallery hosts this show given its proximity to where the the collaboration of its many generous lenders: Allan Bealy and terminal building once stood, just four blocks from 205 Hudson Sheila Keenan of Benzene Magazine; Hal Bromm Gallery and Hal Street. -

Defining and Understanding Street Art As It Relates to Racial Justice In

Décor-racial: Defining and Understanding Street Art as it Relates to Racial Justice in Baltimore, Maryland A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Meredith K. Stone August 2017 © 2017 Meredith K. Stone All Rights Reserved 2 This thesis titled Décor-racial: Defining and Understanding Street Art as it Relates to Racial Justice in Baltimore, Maryland by MEREDITH K. STONE has been approved for the Department of Geography and the College of Arts and Sciences by Geoffrey L. Buckley Professor of Geography Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT STONE, MEREDITH K., M.A., August 2017, Geography Décor-racial: Defining and Understanding Street Art as it Relates to Racial Justice in Baltimore, Maryland Director of Thesis: Geoffrey L. Buckley Baltimore gained national attention in the spring of 2015 after Freddie Gray, a young black man, died while in police custody. This event sparked protests in Baltimore and other cities in the U.S. and soon became associated with the Black Lives Matter movement. One way to bring communities together, give voice to disenfranchised residents, and broadcast political and social justice messages is through street art. While it is difficult to define street art, let alone assess its impact, it is clear that many of the messages it communicates resonate with host communities. This paper investigates how street art is defined and promoted in Baltimore, how street art is used in Baltimore neighborhoods to resist oppression, and how Black Lives Matter is influencing street art in Baltimore. -

Mural Mural on the Wall: Revisiting Fair Use of Street Art

UIC REVIEW OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAW MURAL MURAL ON THE WALL: REVISITING FAIR USE OF STREET ART MADYLAN YARC ABSTRACT Mural mural on the wall, what’s the fairest use of them all? Many corporations have taken advantage of public art to promote their own brand. Corporations commission graffiti advertising campaigns because they create a spectacle that gains traction on social media. The battle rages on between the independent artists who wish to protect the exclusive rights over their art, against the corporations who argue that the public art is fair game and digital advertising is fair use of art. The Eastern Market district of Detroit is home to the Murals in the Market Festival. In January 2018, Mercedes Benz obtained a permit from the City of Detroit to photograph its G 500 SUV in specific downtown areas. On January 26, 2018, Mercedes posted six of these photographs on its Instagram account. When Defendant-artists threatened to file suit, Mercedes removed the photos from Instagram as a courtesy. In March 2019, Mercedes filed three declaratory judgment actions against the artists for non-infringement. This Comment will analyze the claims for relief put forth in Mercedes’ complaint and evaluate Defendant-artists’ arguments. Ultimately, this Comment will propose how the court should rule in the pending litigation of MBUSA LLC v. Lewis. Cite as Madylan Yarc, Mural Mural on the Wall: Revisiting Fair Use of Street Art, 19 UIC REV. INTELL. PROP. L. 267 (2020). MURAL MURAL ON THE WALL: REVISITING FAIR USE OF STREET ART MADYLAN YARC I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 267 A. -

The Writing on the Wall: Graffiti, Street Art, and a New Organic Urban Architecture Name: Isabella Siegel Faculty Adviser: Professor Laura Mcgrane

The Writing on the Wall: Graffiti, Street Art, and a New Organic Urban Architecture Name: Isabella Siegel Faculty Adviser: Professor Laura McGrane In the past half a century, graffiti and street art have grown from roots in Philadelphia to become a worldwide phenomenon. Graffiti is a method of self-expression and defiance that has mutated into new art forms that breach the status quo and gesture toward insurrection. Street art has evolved from such work, as a thriving tradition that works to articulate fears and hopes of a city’s inhabitants on the very buildings they live in. Street art, and graffiti as well, is a complex art form, especially when detangling issues of legality in the U.S. The language of “Organic Architecture” describes the way that the inhabitants of a built space work to determine what fills the empty spaces that remain. Graffiti and street art often constitute the materials with which these inhabitants build. Both genres are methods of expression of a personality, a frustration, or a window into the urban subconscious. These issues speak to Fine Arts and Art History majors, but also to those who study Political Science, History, Economics, Sociology, and Anthropology, and the Growth and Form of Cities. Art history is often used as a bridge into all of these topics, and the study of un-commissioned wall-art is no exception. The insurrectionist political nature of many pieces of street art, and much of graffiti as well, can be studied through the unique lens of someone with a background in political science. -

Press Release Martha Cooper: Taking Pictures

URBAN NATION ALT-MOABIT 101 A NANCY HENZE MOBIL: +49 173 1416030 MUSEUM FOR URBAN D – 10559 BERLIN PRESSE/ TELEFON: +49 30 47081536 CONTEMPORARY ART WWW.URBAN-NATION.COM PUBLIC RELATIONS [email protected] Press Release Icon of street art photography Martha Cooper: Taking Pictures will run at the URBAN NATION museum until 1 August 2021 A first: the opening was also streamed live Martha Cooper photographed by Nika Kramer. After being closed for a month, the URBAN NATION museum reopened last Friday with the exhibition Martha Cooper: Taking Pictures. Over the opening weekend alone, more than 1,300 visitors came to see the US photographer's first comprehensive retrospec- tive. In addition to the museum visitors, more than 700 people interested in the exhibition opening followed it digitally. On the opening evening, the music journalist Falk Schacht and the Dutch graffiti artist Mick La Rock guided the audience through the exhibition via a live stream that also featured exclusive interviews with Martha Cooper, the curators Steven P. Harrington and Jaime Rojo, who are currently in New York, as well as other artists and contemporaries. With the two-part opening concept of a reduced number of visitors at the museum plus a live stream, the URBAN NATION made it possible for Berlin-based as well as worldwide street art and graffiti fans to attend the opening des- pite the social distancing rules. Exhibition shows Martha Cooper's oeuvre The extensive retrospective covers Martha Cooper's artistic output over ten decades and features not only her well-known photographs but also unpublished pictures and personal items. -

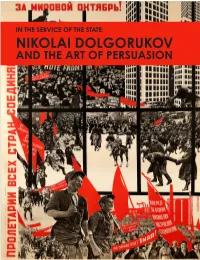

Nikolai Dolgorukov

IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: AGES IM CO U N R T IO E T S Y C E O L L F © T O H C E M N 2020 A E NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV R M R R I E L L B . C AND THE ART OF PERSUASION IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV’ AND THE ART OF PERSUASION NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV’ AND THE ART OF THE STATE: IN THE SERVICE © 2020 Merrill C. Berman Collection IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV AND THE ART OF PERSUASION 1 Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Series Editor, Adrian Sudhalter Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph.D. Content editing by Karen Kettering, Ph.D., Independent Scholar, Seattle, Washington Research assistance by Sofía Granados Dyer, graduate student, Higher School of Economics, Moscow, and Elena Emelyanova, Curator, Rare Books Department, The Russian State Library, Moscow Design, typesetting, production, and photography by Jolie Simpson Copy editing by Madeline Collins Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2020 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted © 2020 the Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Illustrations on pages 39–41 for complete caption information. Cover: Poster: Za Mirovoi Oktiabr’! Proletarii vsekh stran soediniaites’! (Proletariat of the World, Unite Under the Banner of World October!), 1932 Lithograph 57 1/2 x 39 3/8” (146.1 x 100 cm) (p. 103) Acknowledgments We are especially grateful to Sofía Granados Dyer, graduate student at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, for conducting research in various Russian archives as well as for assisting with the compilation of the documentary sections of this publication: Bibliography, Exhibitions, and Chronology. -

A Medici to Spray Paint and Graffiti Artists by FELICIA R

ART & DESIGN A Medici to Spray Paint and Graffiti Artists By FELICIA R. LEE JAN. 28, 2014 From left, the filmmaker Charlie Ahearn and the artist Lee Quiñones at ABC No Rio.CreditDamon Winter/The New York Times “Times have changed,” Aaron Goodstone said stoically, eyeing the spruced-up brick tenement at Ridge and Stanton Streets on the Lower East Side, now hip, where his friend Martin Wong once lived. Thirty years ago, when Mr. Goodstone was a teenage graffiti artist, he vied with drug dealers for the corner pay phone to reach Wong in his buzzerless sixth-floor walk-up: a salon, a studio, an archive and a refuge among the crumbling buildings and gated storefronts. Wong, a major painter in the East Village art scene, who died in 1999, was also a major collector. A mentor to young artists, he amassed about 300 works of graffiti in that small railroad apartment. Nearly 20 years after he donated his collection to the Museum of the City of New York, nearly 150 of those works are in “City as Canvas: Graffiti Art From the Martin Wong Collection.” The first exhibition of Wong’s collection, opening on Tuesday and running through Aug. 24, it is one of several graffiti and street art shows in the United States and abroad at museums and galleries in the past several years. Lee Quiñones’s “Howard the Duck” (1988). CreditMuseum of the City of New York. The exhibition prompted Mr. Goodstone’s recent trek to Wong’s old neighborhood. He was accompanied by the filmmaker Charlie Ahearn (director of the seminal 1983 film “Wild Style,” about New York’s hip-hop and graffiti scene), who shot a 13-minute documentary for “City as Canvas.” The film shows how several artists helped the museum’s curators choose and identify the artworks, some unsigned or misidentified: Mr. -

The Unfamiliar in Modern Art: Street Art As a Model

International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change. www.ijicc.net Volume 12, Issue 10, 2020 The Unfamiliar in Modern Art: Street Art as a Model Rana Meery Mizala, Ibtisam Naji Kadhemb*, aBabylon University/ College of Fine Arts/ Department of Design, bBabylon University/ College of Fine Arts/ Department of Plastic Arts, Email: [email protected], b*[email protected] Contemporary art experiences, including street art, are a holistic phenomenon that works to capture everything that surrounds us socially and psychologically, and melts it in a simulation and study of reality as one of the environmental arts that seeks to beautify and preserve the environment. Thus, we always find it be dynamic, as it attracts the changes that afflict civilisation. We even find that the structure of contemporary conceptual art and environmental art has taken a path different from what was previously mentioned in their construction or completion. The later worked to involve the recipient in its construction by raising questions, leaving that to the recipient to mobilise his cognitive abilities to answer the proposals of the contemporary technical text. The true philosophical significance of the work of art is particularly evident in the face of the artist, for what it is in the world (absurdity or strange), and his rebellion only comes by imposing an organised artistic form on reality (Ibrahim, 2010). The criticism of reasonableness in all its varieties, the glorification of life and its elevations, and limitation to the unfamiliar in the implementation of artwork, lasts for hours and days throughout the perspective body to show the viewer that it is real and three- dimensional. -

A Celebration of Hip Hop Culture & Free Expression

STREET ARTS A Celebration of Hip Hop Culture & Free Expression OCTOBER NOVEMBER 2010 Albuquerque New Mexico 516 ARTS The 5G Gallery ABQ Ride ABQ Trolley Co. ACLU-NM Albuquerque Academy Albuquerque MainStreet The Albuquerque Museum Albuquerque Public Art Program Amy Biehl High School BECA Foundation The Cell Theatre Church of Beethoven Creative Albuquerque Downtown Action Team FUSION Theatre Company Global DanceFest The Guild Cinema KiMo Theatre & Art Gallery KUNM Radio N4th Theater National Hispanic Cultural Center New Studio A.D. The Outpost Performance Space Warehouse 508 Working Classroom CONTENTS Introduction 2 Exhibitions 4 Murals & Tours 6 Hip Hop Film Festival 8 Spoken Word Festival 9 Calendar 10 Performances & Events 12 Talks 14 Join 516 ARTS 16 Credits 17 www.516arts.org • 505-242-1445 STREET ARTS is organized by 516 ARTS, with ACLU-NM & local organizations Visual Art • Spoken Word • Music • Film • Dance • Talks • Tours INTRODUCTION STREET ARTS 3 Starting from Scratch Let’s begin with two generally agreed upon definitions of Hip Hop. One deals in the intangible realm of sensibility and perspective: Hip Hop = Culture. The second refers to the business of selling snapshots and sound-bites gleaned from the culture’s creative expression: Hip Hop = $. If Hip Hop is indeed a way of life, what is that “way?” Consider an apt metaphor derived from a widely known mode of Hip Hop expression, the scratch. Created when the turntablist’s fingers manipulate recorded sound in sync to new musical elements, the scratch is both defiant and tributary. The practice of re-contextualizing sound and symbol is evident in Hip Hop’s signpost elements: “break dancing,” “MC’ing/rapping,” “graffiti,” “beat making” and “beat boxing.” Each challenge the norms of the visual/performance/literary mediums in which they’re associated. -

Street Art: Lesson What Is Street Art? 9 How Is It Diferent from Grafti? Why Can It Be Perceived As Controversial?

Street Art: Lesson What is Street Art? 9 How is it diferent from Grafti? Why can it be perceived as controversial? LESSON OVERVIEW/OBJECTIVES Students will learn about Street Art, its history and evolution. They will explore the differences between Street Art and Graffti and talk about why Street Art can be controversial. Students will learn about a well known street artist named Banksy and his work and style as well as look at samples of street art from aroud the world. Students will use stencils, paints and pens to create their own personal brand in the form of street art. KEY IDEAS THAT CONNECT TO VISUAL ARTS CORE CURRICULUM: Based on Utah State Visual Arts Core Curriculum Requirements (3rd Grade) Standard 1 (Making): The student will explore and refne the application of media, techniques, and artistic processes. Objective 1: Explore a variety of art materials while learning new techniques and processes. b. Use simplifed forms, such as cones, spheres, and cubes, to begin drawing more complex forms. d. Make one color dominant in a painting. e. Create the appearance of depth by drawing distant objects smaller and with less detail than objects in the foreground. Objective 3: Handle art materials in a safe and responsible manner. a. Ventilate the room to avoid inhaling fumes from art materials. b. Dispose and/or recycle waste art materials properly. c. Clean and put back to order art making areas after projects. d. Respect other students’ artworks as well as one’s own. Standard 2 (Perceiving): The student will analyze, refect on, and apply the structures of art.