Images of Guy Fawkes and the Creation of Postmodern Anarchism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How We Became Legion: Burke's Identification and Anonymous By

How We Became Legion: Burke's Identification and Anonymous by Débora Cristina Ramos Antunes da Silva A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in English - Rhetoric and Communication Design Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2013 © Débora Cristina Ramos Antunes da Silva 2013 I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This thesis presents a study of how identification, according to Kenneth Burke's theory, can be observed in the media-related practices promoted by the cyber-activist collective Anonymous. Identification is the capacity of community-building through the use of shared interests. Burke affirms that, as human beings are essentially social, identification is the very aim of any human interaction. Cyber-activism deeply relies on this capacity to promote and legitimise its campaigns. In the case of Anonymous, the collective became extremely popular and is now a frequent presence even in street protests, usually organised online, around the world. Here, I argue that this power was possible through the use of identification, which helped attract a large number of individuals to the collective. Anonymous was particularly skilled in its capacity to create an ideology for each campaign, which worked well to set up a perfect enemy who should be fought against by any people, despite their demographic or social status. Other forms of identification were also present and important. -

A Construção Histórica Na Graphic Novel V for Vendetta: Aspectos Políticos, Sociais E Culturais Na Inglaterra (1982-1988)

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE PELOTAS INSTITUTO DE CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA Dissertação A construção histórica na graphic novel V for Vendetta: aspectos políticos, sociais e culturais na Inglaterra (1982-1988). Felipe Radünz Krüger Pelotas, 2014 2 Felipe Radünz Krüger A construção histórica na graphic novel V for Vendetta: aspectos políticos, sociais e culturais na Inglaterra (1982-1988). Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em História da Universidade Federal de Pelotas, como requisito parcial à obtenção do título de Mestre em História. Orientadora: Profª Drª Larissa Patron Chaves Pelotas, 2014 3 4 Felipe Radünz Krüger A construção histórica na graphic novel V for Vendetta: aspectos políticos, sociais e culturais na Inglaterra da década de 1980 Dissertação aprovada, como requisito parcial, para obtenção do grau de Mestre em História, Programa de Pós-Graduação em História, Universidade Federal de Pelotas. Data da Defesa: 11/04/2014 Banca examinadora: Prof. Dr. Larissa Patron Chaves (Orientador) Doutora em História pela Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos Prof. Dr. Arthur Lima de Avila Doutor em História pela Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul Prof. Dr. Nádia da Cruz Senna Doutora em Ciências da Comunicação pela Universidade de São Paulo Prof. Dr. Aristeu Elisandro Machado Lopes Doutor em História pela Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul 5 Agradecimentos Após o termino da escrita, pensei finalmente ter acabado meu trabalho. Todavia, ao iniciar a formatação do texto, deparei-me com o espaço direcionado aos agradecimentos e comecei automaticamente a lembrar das pessoas responsáveis pela minha formação pessoal e profissional. Após alguns minutos, conclui que por mais que me esforce, não tenho como agradecer a todos os que ajudaram a formar o indivíduo e o historiador que sou hoje. -

Icons of Survival: Metahumanism As Planetary Defense." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture

Lioi, Anthony. "Icons of Survival: Metahumanism as Planetary Defense." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 169–196. Environmental Cultures. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 25 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474219730.ch-007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 25 September 2021, 20:32 UTC. Copyright © Anthony Lioi 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 6 Icons of Survival: Metahumanism as Planetary Defense In which I argue that superhero comics, the most maligned of nerd genres, theorize the transformation of ethics and politics necessary to the project of planetary defense. The figure of the “metahuman,” the human with superpowers and purpose, embodies the transfigured nerd whose defects—intellect, swarm-behavior, abnormality, flux, and love of machines—become virtues of survival in the twenty-first century. The conflict among capitalism, fascism, and communism, which drove the Cold War and its immediate aftermath, also drove the Golden and Silver Ages of Comics. In the era of planetary emergency, these forces reconfigure themselves as different versions of world-destruction. The metahuman also signifies going “beyond” these economic and political systems into orders that preserve democracy without destroying the biosphere. Therefore, the styles of metahuman figuration represent an appeal to tradition and a technique of transformation. I call these strategies the iconic style and metamorphic style. The iconic style, more typical of DC Comics, makes the hero an icon of virtue, and metahuman powers manifest as visible signs: the “S” of Superman, the tiara and golden lasso of Wonder Woman. -

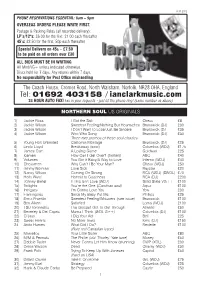

Clarky List 50 31/07/2012 13:06 Page 1

Clarky List 51_Clarky List 50 31/07/2012 13:06 Page 1 JULY 2012 PHONE RESERVATIONS ESSENTIAL : 8am – 9pm OVERSEAS ORDERS PLEASE WRITE FIRST. Postage & Packing Rates (all recorded delivery): LP’s/12"s: £6.00 for the first, £1.00 each thereafter 45’s: £2.50 for the first, 50p each thereafter Special Delivery on 45s – £7.50 to be paid on all orders over £30 ALL BIDS MUST BE IN WRITING All Mint/VG+ unless indicated otherwise. Discs held for 7 days. Any returns within 7 days. No responsibility for Post Office mis han dling The Coach House, Cromer Road, North Walsham, Norfolk, NR28 0HA, England Tel: 01692 403158 / ianclarkmusic.com 24 HOUR AUTO FAX! Fax in your requests - just let the phone ring! (same number as above) NORTHERN SOUL US ORIGINALS 1) Jackie Ross I Got the Skill Chess £8 2) Jackie Wilson Sweetest Feeling/Nothing But Heartaches Brunswick (DJ) £30 3) Jackie Wilson I Don’t Want to Lose/Just Be Sincere Brunswick (DJ £35 4) Jackie Wilson Who Who Song Brunswick (DJ) £30 Three rare promos of these soul classics 5) Young Holt Unlimited California Montage Brunswick (DJ) £25 6) Linda Lloyd Breakaway (swol) Columbia (WDJ) £175 7) James Carr A Losing Game Goldwax £25 8) Icemen How Can I Get Over? (brilliant) ABC £40 9) Volumes You Got it Baby/A Way to Love Inferno (WDJ) £40 10) Chessmen Why Can’t I Be Your Man? Chess (WDJ) £50 11) Jimmy Norman Love Sick Raystar £20 12) Nancy Wilcox Coming On Strong RCA (WDJ) (SWOL) £70 13) Herb Ward Honest to Goodness RCA (DJ) £200 14) Johnny Bartel If This Isn’t Love (WDJ) Solid State VG++ £100 15) Twilights -

Text and Image in Translation

CLEaR, 2016, 3(2), ISSN 2453 - 7128 DOI: 10.1515/clear - 2016 - 0013 Text and Image in T ranslation Milena Yablonsky Pedagogical University of Cracow, Poland [email protected] Abstract The primary objective of the following paper is t he analysis of selected issues related to the translation of comic books. The paper aims at investigating the relationships between the text and the image and their implications in the process of translation. It reflects on the status of the translation of comics/graphic novels - a still largely unexp loited area within Translation Studies and briefly presents a definition and specificity of the genre. Moreover, it discusses Jakobson’s (1971) tripartite distinction into interlinguistic, intralinguistic and intersemiotic translation. The paper concludes with the analysis of certain issues associated with the Polish translation of V like Vendetta by Alan Moore, a text that is copious with intertextual and cultural references. Keywords: graphic novel, comics, V like Vendetta , Jakobson, constrained translat ion, intertextuality Introduction The translation of comic books still occupies a rather unexploited area within the discipline of Translation Studies, maybe due to the fact that it “might be perceived as a field of l esser interest” (Zanettin 273) and comics are usually regarded as an artistic form of a lower status. In Dictionary of Translation Studies by Shuttleworth and Cowie there is no t a single entry on comics. They refer to them only when they explain the term “multi - medial texts” ( 109 - 1 10) as: “ . The multi - medial category consists of texts in which the ver bal content is supplemented by elements in other media; however, all such texts will also simultaneously belong to one of the other, main text - type . -

Satan's Sibling - Poems

Poetry Series Satan's Sibling - poems - Publication Date: 2008 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Satan's Sibling(15/03/1990) I am a poetry enthusiast with a variety of poetry styles. Some are love poems, some are hate poems. But I guess that love and hate are the basis of life, Aren't they? (My motto for life is 'There is no God, he is a figment of our imagination. There is no Karma, we punish ourselves. No destiny, we choose our own path. No freedom. We are bound by our own laws. For now.) www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 1 Million Years Bc (Lyrics) They're calling me, the creatures of the nigh, Beautiful music, Animal instincts survived, the serpent tongue, so ancient before the dawn of time, Spread throughout the ages, On the blood of mankind. I've seen it all. From grace man falls, Babylon, curse of all creation, Winged serpent of the pit, Monstrosity. Ten thousand centuries ago, Cast down from heaven, To pillage below, The serpents eye, Still watching for it's easy prey, Feed upon the hopeless, the weak and afraid. I've seen it all. From grace men fall, Babylon, curse of all creation. Winged serpent of the pit, Monstrosity. 1 million yeasr bc x3 Satan's Sibling www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 2 8 Line Poem (Lyrics) The tactful cactus by your window Surveys the prairie of your room The mobile spins to its collision Clara puts her head between her paws They've opened shops down West side Will all the cacti find a home But the key to the city Is in the sun that pins the branches to the sky Satan's Sibling www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 3 A Desirable Complication I sit here in anguish, Silently suffering. -

Stewart2019.Pdf

Political Change and Scottish Nationalism in Dundee 1973-2012 Thomas A W Stewart PhD Thesis University of Edinburgh 2019 Abstract Prior to the 2014 independence referendum, the Scottish National Party’s strongest bastions of support were in rural areas. The sole exception was Dundee, where it has consistently enjoyed levels of support well ahead of the national average, first replacing the Conservatives as the city’s second party in the 1970s before overcoming Labour to become its leading force in the 2000s. Through this period it achieved Westminster representation between 1974 and 1987, and again since 2005, and had won both of its Scottish Parliamentary seats by 2007. This performance has been completely unmatched in any of the country’s other cities. Using a mixture of archival research, oral history interviews, the local press and memoires, this thesis seeks to explain the party’s record of success in Dundee. It will assess the extent to which the character of the city itself, its economy, demography, geography, history, and local media landscape, made Dundee especially prone to Nationalist politics. It will then address the more fundamental importance of the interaction of local political forces that were independent of the city’s nature through an examination of the ability of party machines, key individuals and political strategies to shape the city’s electoral landscape. The local SNP and its main rival throughout the period, the Labour Party, will be analysed in particular detail. The thesis will also take time to delve into the histories of the Conservatives, Liberals and Radical Left within the city and their influence on the fortunes of the SNP. -

“Why So Serious?” Comics, Film and Politics, Or the Comic Book Film As the Answer to the Question of Identity and Narrative in a Post-9/11 World

ABSTRACT “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD by Kyle Andrew Moody This thesis analyzes a trend in a subgenre of motion pictures that are designed to not only entertain, but also provide a message for the modern world after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The analysis provides a critical look at three different films as artifacts of post-9/11 culture, showing how the integration of certain elements made them allegorical works regarding the status of the United States in the aftermath of the attacks. Jean Baudrillard‟s postmodern theory of simulation and simulacra was utilized to provide a context for the films that tap into themes reflecting post-9/11 reality. The results were analyzed by critically examining the source material, with a cultural criticism emerging regarding the progression of this subgenre of motion pictures as meaningful work. “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Mass Communications Area by Kyle Andrew Moody Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2009 Advisor ___________________ Dr. Bruce Drushel Reader ___________________ Dr. Ronald Scott Reader ___________________ Dr. David Sholle TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... III CHAPTER ONE: COMIC BOOK MOVIES AND THE REAL WORLD ............................................. 1 PURPOSE OF STUDY ................................................................................................................................... -

S Jews in World War II

The Rescue of Bulgaria's Jews in World War II ON FEBRUARY 13, 1998, Bulgarian President Petar Stoyanov accepted on behalf of his ex-Communist nation the Courage to Care Award, which the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) had bestowed upon Bulgaria in recognition of the heroism of its people in saving Bulgarian Jews during World War II. Speaking at a meeting of the League's National Executive Committee in Palm Beach, Florida, the ADL National Director Abraham Foxman presented this prestigious award to President Stoyanov with words of deep gratitude: "Today I am here to say thank you — thank you to a people and a nation that unanimously said 'no' to the Nazi killing machine, 'no' to the deportation trains and concentration camps, and 'yes' to its 48,000 Jews."[1] He praised the Bulgarian people who heroically saved the local Jews by preventing their deportation to Hitler's death camps, even though the Bulgarian government was allied with Nazi Germany during World War II. According to Mr. Foxman, this miraculous salvation of Bulgaria's Jewish community was made possible by the courageous leadership of Bulgarian King Boris III, "whose personal defiance of Hitler and refusal to supply troops to the Russian front or to cooperate with deportation requests set an example for his country."[2] Thanking his host for this high honor, President Stoyanov replied with some modesty, "What happened then should not be seen as a miracle. My nation did what any decent nation, human being, man or woman, would have done in those circumstances…. The events of World War II have made the Bulgarian Jews forever the closest friends of my people."[3] On March 11, 2003, Bulgaria's international image got an even bigger boost, when the U.S. -

V for Vendetta’: Book and Film

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE ESTUDOS ANGLÍSTICOS “9 into 7” Considerations on ‘V for Vendetta’: Book and Film. Luís Silveiro MESTRADO EM ESTUDOS INGLESES E AMERICANOS (Estudos Norte-Americanos: Cinema e Literatura) 2010 UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE ESTUDOS ANGLÍSTICOS “9 into 7” Considerations on ‘V for Vendetta’: Book and Film. Luís Silveiro Dissertação orientada por Doutora Teresa Cid MESTRADO EM ESTUDOS INGLESES E AMERICANOS (Estudos Norte-Americanos: Cinema e Literatura) 2010 Abstract The current work seeks to contrast the book version of Alan Moore and David Lloyd‟s V for Vendetta (1981-1988) with its cinematic counterpart produced by the Wachowski brothers and directed by James McTeigue (2005). This dissertation looks at these two forms of the same enunciation and attempts to analise them both as cultural artifacts that belong to a specific time and place and as pseudo-political manifestos which extemporize to form a plethora of alternative actions and reactions. Whilst the former was written/drawn during the Thatcher years, the film adaptation has claimed the work as a herald for an alternative viewpoint thus pitting the original intent of the book with the sociological events of post 9/11 United States. Taking the original text as a basis for contrast, I have relied also on Professor James Keller‟s work V for Vendetta as Cultural Pastiche with which to enunciate what I consider to be lacunae in the film interpretation and to understand the reasons for the alterations undertaken from the book to the screen version. An attempt has also been made to correlate Alan Moore‟s original influences into the medium of a film made with a completely different political and cultural agenda. -

Overthrowing Vengeance: the Role of Visual Elements in V for Vendetta

Overthrowing Vengeance: The Role of Visual Elements in V for Vendetta Pedro Moreira University of Porto, Portugal Citation: Pedro Moreira, ”Overthrowing Vengeance: The Role of Visual Elements in V for Vendetta ”, Spaces of Utopia: An Electronic Journal , nr. 4, Spring 2007, pp. 106-112 <http://ler.letras.up.pt > ISSN 1646-4729. Introduction The emergence of the critical dystopia genre in the 1980s allowed for the appearance of a body of literature capable of both informing and prompting readers to action. The open-endness of these works, coupled with the sense of critique, becomes a key element in performing a catalyst function and maintaining hope within the text. V for Vendetta , by Alan Moore, with illustrations by David Lloyd, first published in serial form between 1982 and 1988 and, later, in 1990, as a graphic novel is one of such works. Appearing during the political climate of Margaret Thatcher’s conservative government, it became a cult classic amongst graphic novels readers and collectors. A film adaptation was released in 2006, from a screenplay by the Wachowski brothers, to different reactions from the graphic novel’s creators; Moore withdrew his support and denied any involvement in the adaptation while David Lloyd publicly confessed his admiration for the movie. I first became interested in the series due to its gritty realism, and the enigmatic, cultured figure of the protagonist. In fact, V for Vendetta ’s universe is quite distant from the comic book genre, which is dominated by God-like figures such as Superman or Spiderman. Also, the sheer scope of reference in the work, ranging from Blake and Shakespeare to the Rolling Stones and The Velvet Underground, added to my interest, making it the subject of this paper. -

Structures of Desire: Postanarchist Kink in the Speculative Fiction Of

Chapter 7 Structures of desire Postanarchist kink in the speculative fiction of Octavia Butler and Samuel Delany Lewis Call It's a beautiful universe ... wondrous and the more exciting because no one has written plays and poems and built sculptures to indicate the structure of desire I negotiate every day as I move about in it. -Samuel Delany, Stars in My Pocket Like Grains of Sand The problem of power is one of the major philosophical and political preoccupations of the modern West. It is a problem which has drawn the attention of some of the greatest minds of the nineteenth and twentieth cen turies, including Fried~ich Nietzsche and Michel Foucault. I have argued else where that the philosophies of power articulated by Nietzsche and Foucault stand as prototypes of an innovative form of anarchist theory, one which finds liberatory potential in the disintegration of the modern self and its liberal humanist politics (Call 2002: chs 1 and 2). Lately this kind of theory has become known as postanarchism. For me, postanarchism refers to a form of contemporary anarchist theory which draws extensively upon postmodern and poststructuralist philosophy in order to push anarchism beyond its traditional boundaries. Postanarchism tries to do this by adding important new ideas to anarchism's traditional critiques of statism and capitalism. Two of these ideas are especially significant for the present essay: the Foucauldian philosophy of power, which sees power as omnipresent but allows us to distinguish between power's various forms, and the Lacanian concept of subjectivity, which understands the self to be constituted by and through its desire.