Original English Text Of: Die Kosmogonie Des Alten

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Inanna Research Script

INANNA RESEARCH SCRIPT (to be cut and shaped for performance) By Peggy Firestone Based on Translations of Clay Tablets from Sumer By Samuel Noah Kramer 1 [email protected] (773) 384-5802 © 2008 CAST OF CHARACTERS In order of appearance Narrators ………………………………… Storytellers & Timekeepers Inanna …………………………………… Queen of Heaven and Earth, Goddess, Immortal Enki ……………………………………… Creator & Organizer of Earth’s Living Things, Manager of the Gods & Goddesses, Trickster God, Inanna’s Grandfather An ………………………………………. The Sky God Ki ………………………………………. The Earth Goddess (also known as Ninhursag) Enlil …………………………………….. The Air God, inventor of all things useful in the Universe Nanna-Sin ………………………………. The Moon God, Immortal, Father of Inanna Ningal …………………………………... The Moon Goddess, Immortal, Mother of Inanna Lilith ……………………………………. Demon of Desolation, Protector of Freedom Anzu Bird ………………………………. An Unholy (Holy) Trinity … Demon bird, Protector of Cattle Snake that has no Grace ………………. Tyrant Protector Snake Gilgamesh ……………………………….. Hero, Mortal, Inanna’s first cousin, Demi-God of Uruk Isimud ………………………………….. Enki’s Janus-faced messenger Ninshubur ……………………………… Inanna’s lieutenant, Goddess of the Rising Sun, Queen of the East Lahamma Enkums ………………………………… Monster Guardians of Enki’s Shrine House Giants of Eridu Utu ……………………………………… Sun God, Inanna’s Brother Dumuzi …………………………………. Shepherd King of Uruk, Inanna’s husband, Enki’s son by Situr, the Sheep Goddess Neti ……………………………………… Gatekeeper to the Nether World Ereshkigal ……………………………. Queen of the -

®Ht Telict11ria Jnstitut~

JOURNAL OF THE TRANSACTIONS OF ®ht telict11ria Jnstitut~, on, Jgifosopgital Sodd~ of ~nat Jrifain. EDITED BY THE HONORARY SECHETARY, CAPTAIN F. W. H. PETRIE, F.G.S., &c. VOL. XXVIII. UON DON~: (Jluuli~clr b!! tbc :IEnstitutr, 8, \!llt'lpl)i et:crracr, ~baring ~rtrss, §".~.) INDIA: w. THACKER & Co. UNITED STATES: G. T. PUTN.AM'S SONS, JS. r. AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND: G. ROBERTSON & Co. Lrn. CAN.ADA: DAWSON BROS., Montreal. S . .AFRICA: JUTA & Co., Cape 1'own. PARIS: GALIGNANI. 1896. ALL RIG H T S RES E 11, Y ED, JOURNAL OF THE TRANSACTIONS OF THB VICTORIA INSTITUTE, OR PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY OF GREAT BRITAIN --+- ORDINARY MEETING.* PROFESSOR E. HULL, LL.D., F.R.S., IN THE CHAIR. The Minutes of the last Meeting were read and confirmed, and the following paper was read by the author :- THE RELIGIOUS IDEAS OF THE BABYLONIANS.t ~ By THEO. G. PINCHES. HE most extensive work upon the religion of the T Babylonians is Prof. Sayce's book, which forms the volume of the Hibbert Lectures for 1887 ; a voluminous work; and a monument of brilliant research. The learned author there quotes all the legends, from every source, connected .with Babylonian religion and mythology, and this book will always be indispensable to the student in that branch of Assyriology. I do not intend, however, to traverse the ground covered by Prof. Sayce, for a single lecture, such as this is, would be altogether inadequate for the purpose. I shall merely confine myself, therefore, to the points which have not been touched upon by others in this field, and I hope that I may be able to bring fot·ward something that may interest my audience and my readers. -

Cuneiform Monographs

VANSTIPHOUT/F1_i-vi 4/26/06 8:08 PM Page ii Cuneiform Monographs Editors t. abusch ‒ m.j. geller s.m. maul ‒ f.a.m. wiggerman VOLUME 35 frontispiece 4/26/06 8:09 PM Page ii Stip (Dr. H. L. J. Vanstiphout) VANSTIPHOUT/F1_i-vi 4/26/06 8:08 PM Page iii Approaches to Sumerian Literature Studies in Honour of Stip (H. L. J. Vanstiphout) Edited by Piotr Michalowski and Niek Veldhuis BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2006 VANSTIPHOUT/F1_i-vi 4/26/06 8:08 PM Page iv This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on http: // catalog.loc.gov ISSN 0929-0052 ISBN-10 90 04 15325 X ISBN-13 978 90 04 15325 7 © Copyright 2006 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill Academic Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. printed in the netherlands VANSTIPHOUT/F1_i-vi 4/26/06 8:08 PM Page v CONTENTS Piotr Michalowski and Niek Veldhuis H. L. J. Vanstiphout: An Appreciation .............................. 1 Publications of H. -

Burn Your Way to Success Studies in the Mesopotamian Ritual And

Burn your way to success Studies in the Mesopotamian Ritual and Incantation Series Šurpu by Francis James Michael Simons A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Classics, Ancient History and Archaeology School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham March 2017 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The ritual and incantation series Šurpu ‘Burning’ is one of the most important sources for understanding religious and magical practice in the ancient Near East. The purpose of the ritual was to rid a sufferer of a divine curse which had been inflicted due to personal misconduct. The series is composed chiefly of the text of the incantations recited during the ceremony. These are supplemented by brief ritual instructions as well as a ritual tablet which details the ceremony in full. This thesis offers a comprehensive and radical reconstruction of the entire text, demonstrating the existence of a large, and previously unsuspected, lacuna in the published version. In addition, a single tablet, tablet IX, from the ten which comprise the series is fully edited, with partitur transliteration, eclectic and normalised text, translation, and a detailed line by line commentary. -

Eski Anadolu Ve Eski Mezopotamya'da Tanrıça Kültleri

T.C. NECMETTİN ERBAKAN ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TARİH ANABİLİM DALI ESKİÇAĞ TARİHİ BİLİM DALI ESKİ ANADOLU VE ESKİ MEZOPOTAMYA’DA TANRIÇA KÜLTLERİ KADER BAĞDERE YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ DANIŞMAN: DOÇ. DR. MUAMMER ULUTÜRK KONYA-2021 T.C. NECMETTİN ERBAKAN ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TARİH ANABİLİM DALI ESKİÇAĞ TARİHİ BİLİM DALI ESKİ ANADOLU VE ESKİ MEZOPOTAMYA’DA TANRIÇA KÜLTLERİ KADER BAĞDERE YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ DANIŞMAN: DOÇ. DR. MUAMMER ULUTÜRK KONYA-2021 T.C. NECMETTİN ERBAKAN ÜNİVERSİTESİ Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Müdürlüğü BİLİMSEL ETİK SAYFASI Adı Soyadı Kader Bağdere Numarası 18810501035 Ana Bilim / Bilim Dalı Tarih/Eskiçağ Programı Tezli Yüksek Lisans X Doktora Öğrencinin Tezin Adı Eski Anadolu ve Eski Mezopotamya’da Tanrıça Kültleri Bu tezin hazırlanmasında bilimsel etiğe ve akademik kurallara özenle riayet edildiğini, tez içindeki bütün bilgilerin etik davranış ve akademik kurallar çerçevesinde elde edilerek sunulduğunu, ayrıca tez yazım kurallarına uygun olarak hazırlanan bu çalışmada başkalarının eserlerinden yararlanılması durumunda bilimsel kurallara uygun olarak atıf yapıldığını bildiririm. Öğrencinin Adı Soyadı İmzası i T.C. NECMETTİN ERBAKAN ÜNİVERSİTESİ Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Müdürlüğü ÖZET Adı Soyadı Kader Bağdere Numarası 18810501035 Tarih/Eskiçağ Tarihi Ana Bilim / Bilim Dalı Tezli Yüksek Lisans X Programı Doktora Öğrencinin Tez Danışmanı Doç. Dr. Muammer Ulutürk Eski Anadolu ve Eski Mezopotamya’da Tanrıça Kültleri Tezin Adı Anadolu ve Mezopotamya yüzyıllar boyunca pek çok medeniyete ev sahipliği yapmıştır. Bu topraklar üzerinde birçok kavim doğmuş, varlığını sürdürmüş ve yok olmuştur. Bu bölgeler çok uluslu bir yapıya sahiptir. Çok uluslu olması, dinin de çok tanrılı olmasına neden olmuştur. Hem Anadolu’da hem Mezopotamya’da birçok tanrıça inanışı oluşmuştur. Anadolu’nun en mühim tanrıçası Kibele’dir. -

The Fifty Names of Marduk.Pdf

The Fifty names of Marduk What we find in the list of the names of Marduk, head of the Mesopotamian divine pantheon, as listed in the Enuma Elish (‘When on High’), is the name of each aspect of Marduk followed by a short description of the powers and properties which each name represents. Taken together, these descriptions of the aspects of Marduk provide a catalogue of divine qualities, and consequently, since the duty of the Mesopotamian king is to emulate the qualities of the gods, also provide a catalogue of the qualities required in the king. It isn't necessary to review all of the names for the purpose of this study - the first ten are reviewed, plus some later names in the list, and the colophon. The translation of the text is by E.A Speiser, from his: Enuma Elish, The Fifty Names of Marduk, (Tablet VIb – VII). What I'm interested in here is the underlying rationale for this collection of names, properties and attributes. It is well known that the divine pantheon in Mesopotamia was subject to local politics and changes in rulership and cultural hegemony, and I am not challenging that at all. However it was possible for properties and attributes to be reassigned, and transferred to other deities. And they were so reassigned. I'm interested in the properties and attributes of Marduk as they appear in the Enuma Elish, and what can be understood of the process by which the list was generated. Samuel Noah Kramer commented, with some puzzlement, on a Sumerian list of disparate things which were white, which I referred to earlier. -

The Lost Book of Enki.Pdf

L0ST BOOK °f6NK1 ZECHARIA SITCHIN author of The 12th Planet • . FICTION/MYTHOLOGY $24.00 TH6 LOST BOOK OF 6NK! Will the past become our future? Is humankind destined to repeat the events that occurred on another planet, far away from Earth? Zecharia Sitchin’s bestselling series, The Earth Chronicles, provided humanity’s side of the story—as recorded on ancient clay tablets and other Sumerian artifacts—concerning our origins at the hands of the Anunnaki, “those who from heaven to earth came.” In The Lost Book of Enki, we can view this saga from a dif- ferent perspective through this richly con- ceived autobiographical account of Lord Enki, an Anunnaki god, who tells the story of these extraterrestrials’ arrival on Earth from the 12th planet, Nibiru. The object of their colonization: gold to replenish the dying atmosphere of their home planet. Finding this precious metal results in the Anunnaki creation of homo sapiens—the human race—to mine this important resource. In his previous works, Sitchin com- piled the complete story of the Anunnaki ’s impact on human civilization in peacetime and in war from the frag- ments scattered throughout Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian, Assyrian, Hittite, Egyptian, Canaanite, and Hebrew sources- —the “myths” of all ancient peoples in the old world as well as the new. Missing from these accounts, however, was the perspective of the Anunnaki themselves What was life like on their own planet? What motives propelled them to settle on Earth—and what drove them from their new home? Convinced of the existence of a now lost book that formed the basis of THE lost book of ENKI MFMOHCS XND PKjOPHeCieS OF XN eXTfCXUfCWJTWXL COD 2.6CHXPJA SITCHIN Bear & Company Rochester, Vermont — Bear & Company One Park Street Rochester, Vermont 05767 www.InnerTraditions.com Copyright © 2002 by Zecharia Sitchin All rights reserved. -

3 a Typology of Sumerian Copular Clauses36

3 A Typology of Sumerian Copular Clauses36 3.1 Introduction CCs may be classified according to a number of characteristics. Jagersma (2010, pp. 687-705) gives a detailed description of Sumerian CCs arranged according to the types of constituents that may function as S or PC. Jagersma’s description is the most detailed one ever written about CCs in Sumerian, and particularly, the parts on clauses with a non-finite verbal form as the PC are extremely insightful. Linguistic studies on CCs, however, discuss the kind of constituents in CCs only in connection with another kind of classification which appears to be more relevant to the description of CCs. This classification is based on the semantic properties of CCs, which in turn have a profound influence on their grammatical and pragmatic properties. In this chapter I will give a description of CCs based mainly on the work of Renaat Declerck (1988) (which itself owes much to Higgins [1979]), and Mikkelsen (2005). My description will also take into account the information structure of CCs. Information structure is understood as “a phenomenon of information packaging that responds to the immediate communicative needs of interlocutors” (Krifka, 2007, p. 13). CCs appear to be ideal for studying the role information packaging plays in Sumerian grammar. Their morphology and structure are much simpler than the morphology and structure of clauses with a non-copular finite verb, and there is a more transparent connection between their pragmatic characteristics and their structure. 3.2 The Classification of Copular Clauses in Linguistics CCs can be divided into three main types on the basis of their meaning: predicational, specificational, and equative. -

The Mesopotamian Origins of Byzantine Symbolism and Early Christian Iconography

The Mesopotamian Origins of Byzantine Symbolism and Early Christian Iconography BY PAUL JOSEPH KRAUSE The eagle-god is a prominent iconographic symbol of ancient Mesopotamian religion which wielded tremendous power in the Mesopotamian imagination. The eagle-like gods of Mesopotamia eventually evolved into double-headed gods whose depictions became widespread in imperial and religious symbolism and iconography in Sumer and Akkad.1 These symbols now have common misapprehension as in the common public as being tied to Byzantine Empire of Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Rather, the Byzantines most likely inherited these Mesopotamian symbols and employed them in a similar manner as the Sumerians, Akkadians, and Hittites did. Likewise, the iconographic symbols of the moon god Nanna-Sin, who had the power to render the fate of humans,2 re-appeared in early Christian iconography depicting Christ in the Last Judgment. To best understand the iconographic practices and symbols used by the Byzantine Empire and emerging early Christian Church is to understand the foundational contexts by which these symbols first arose and the common religious practice of transferring and re-dedicating prior religious shrines to new deities. “Today the Byzantine eagle flutters proudly from the flags of nations from Albania to Montenegro, and though each state has its local version of the church, the heritage they all bear 1 C.N. Deedes, “The Double-Headed God,” Folklore 46, no. 3 (1935): 197-200. 2 See Samuel Noah Kramer, The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1971), 132; Georges Roux, Ancient Iraq (New York: Penguin Books, 1992), 88. -

Mesopotamian Mythology

MESOPOTAMIAN MYTHOLOGY The myths, epics, hymns, lamentations, penitential psalms, incantations, wisdom literature, and handbooks dealing with rituals and omens of ancient Mesopotamian. The literature that has survived from Mesopotamian was written primarily on stone or clay tablets. The production and preservation of written documents were the responsibility of scribes who were associated with the temples and the palace. A sharp distinction cannot be made between religious and secular writings. The function of the temple as a food redistribution center meant that even seemingly secular shipping receipts had a religious aspect. In a similar manner, laws were perceived as given by the gods. Accounts of the victories of the kings often were associated with the favor of the gods and written in praise of the gods. The gods were also involved in the established and enforcement of treaties between political powers of the day. A large group of texts related to the interpretations of omens has survived. Because it was felt that the will of the gods could be known through the signs that the gods revealed, care was taken to collect ominous signs and the events which they preached. If the signs were carefully observed, negative future events could be prevented by the performance of appropriate apotropaic rituals. Among the more prominent of the Texts are the shumma izbu texts (“if a fetus…”) which observe the birth of malformed young of both animals and humans. Later a similar series of texts observed the physical characteristics of any person. There are also omen observations to guide the physician in the diagnosis and treatment of patients. -

Lambert Walcot Kadmos 4 Dunnu

WARNING OF COPYRIGHT RESTRICTIONS1 The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, U.S. Code) governs the maKing of photocopies or other reproductions of the copyright materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, library and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than in private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user maKes a reQuest for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. The Yale University Library reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order, if, in its judgement fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. 137 C.F.R. §201.14 2018 KADMOS ZEITSCHRIFT FOR VOR- UND FRÜHGRIECHISCIIE EPIGRAPHIK IN VERBINDUNG MIT: EMMETT L. BENNETT-MADISON • WILLIAM C. BRICE-MANCHESTER PORPHYRIOS DIKAIOS-WALTHAM • KONSTANTINOS D. KTISTOPOULOS ATHENN. OLIVIER MASSON-PARIS • PIERO MERIGGI-PAVIA • FRITZ SCHACHE RMEYR-WIEN - JOHANNES SUNDWALL-HELSINGFORS HERAUSGEGEBEN VON ERNST GRUMACH BAND IV / HEFT 1 WA LTER DE G R U Y T E R & CO. / BERLIN LUNG - J. G. VERLAG 1TAhCOMP. ~ U CHHANDLUUNG -EORGG REIMER SK IKARL J.TRUBNER TTVE 1965 WILFRED G. LAMBERT and PETER WALCOT1 A NEW BABYLONIAN THEOGONY AND HESIOD A volume of cuneiform texts just published by the British Museum2 contains a short theogony, which is of interest to Classical scholars since it is closer to Hesiod's opening list of gods than any other cuneiform material of this category. -

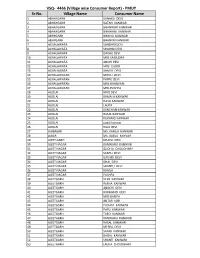

Sr No. Village Name Consumer Name VSQ- 4466 (Village Wise Consumer Report)

VSQ- 4466 (Village wise Consumer Report) - PMUY Sr No. Village Name Consumer Name 1 ABHAYGARH KANAKU DEVI 2 ABHAYGARH RATAN KANWAR 3 ABHAYGARH BHANWAR KANWAR 4 ABHAYGARH BHAWANI KANWAR 5 ABHYGARH BHIKHU KANWAR 6 ABHYGARH BHANVRI KANWAR 7 ACHALAWATA SUNDARI DEVI 8 ACHALAWATA SHOBHA DEVI 9 ACHALAWATA DAKHU DEVI 10 ACHALAWATA MRS SAMUDRA 11 ACHALAWATA ANOPI DEVI 12 ACHALAWATA MRS GUDDI 13 ACHALAWATA KAMLA DEVI 14 ACHALAWATAN MOOLI DEVI 15 ACHALAWATAN PAPPU DEVI 16 ACHALAWATAN MRS BHANVARI 17 ACHALAWATAN MRS PUSHPA 18 AGOLAI HIRO DEVI 19 AGOLAI KAMALA KANWAR 20 AGOLAI HAVA KANWAR 21 AGOLAI LALITA 22 AGOLAI KANCHAN KANWAR 23 AGOLAI RASAL KANWAR 24 AGOLAI RUKAMO KANWAR 25 AGOLAI guddi kanwar 26 AGOLAI RAJO DEVI 27 AJABASAR MS. KAMLA KANWAR 28 AJBAR MS. BABLU KANVAR 29 AJEET GARH DHAPU DEVI 30 AJEET NAGAR KANWARU KANWAR 31 AJEET NAGAR GUDIYA CHOUDHARY 32 AJEET NAGAR SANTU DEVI 33 AJEET NAGAR GAVARI DEVI 34 AJEET NAGAR DHAI DEVI 35 AJEET NAGAR SHANTU DEVI 36 AJEET NAGAR KAMLA . 37 AJEET NAGAR PUSHPA . 38 AJEETGARH VEER KANWAR 39 AJEETGARH REKHA KANWAR 40 AJEETGARH ANACHI DEVI 41 AJEETGARH RUKHAMO DEVI 42 AJEETGARH MRS BABITA 43 AJEETGARH ANTAR KOR 44 AJEETGARH PUSHPA KANWAR 45 AJEETGARH PAPU KANWAR 46 AJEETGARH TARO KANWAR 47 AJEETGARH KANWARU KANWAR 48 AJEETGARH RASAL KANWAR 49 AJEETGARH MEERA DEVI 50 AJEETGARH SAYAR KANWAR 51 AJEETGARH BADAL KANWAR 52 AJEETGARH SHANTI KANWAR 53 AJEETGARH LALITA CHOUDHARY Sr No. Village Name Consumer Name 54 AJEETGARH PEP KANWAR 55 AJEETGARH RASAL KANWAR 56 AJEETGARH JASU KANWAR 57 AJEETGARH LILA KANWAR 58 AJEETGARH KHAMMA DEVI 59 AJIT GADH SUGAN KANWAR 60 AJITGARH CHIMU DEVI 61 AJITGARH KANWARU KANWAR 62 AJJETGADH SOHNI DEVI 63 AKADEEYAWALA MAGEJ KANWAR 64 ALIDAS NAGAR PAPPU KANWAR 65 ALIDAS NAGAR PARVATI DEVI 66 ALIDAS NAGAR NAINU KANWAR 67 ALIDAS NAGAR MOHANI DEVI 68 ALIDAS NAGAR PISTA DEVI 69 ALIDAS NAGAR PRAKASH KANWAR 70 ALIDAS NAGAR NAKHTU DEVI 71 ALIDAS NAGAR DHAPU .