The Journey from Instrumentalist to Musician

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Money from Music: Survey Evidence on Musicians’ Revenue and Lessons About Copyright Incentives

MONEY FROM MUSIC: SURVEY EVIDENCE ON MUSICIANS’ REVENUE AND LESSONS ABOUT COPYRIGHT INCENTIVES Peter DiCola* According to the incentive theory of copyright, financial rewards are what the public trades for the production of creative works. To know whether this quid pro quo is working, one needs to know how much the creators are getting from the bargain. Based on an original, nationwide survey of more than 5,000 musicians, this Article addresses one of the key links in the incentive theory’s chain of logic. For most musicians, copyright does not provide much of a direct financial reward for what they are producing currently. The survey findings are instead consistent with a winner-take-all or superstar model in which copyright motivates musicians through the promise of large rewards in the future in the rare event of wide popularity. * Associate Professor, Northwestern University School of Law. A.B. 1998, Princeton University; J.D. 2005, Ph.D. (Economics) 2009, University of Michigan. I am grateful to my colleagues Jean Cook and Kristin Thomson of the Future of Music Coalition. We worked together to develop and analyze the Internet survey of musicians discussed in this Article, and I have benefited greatly from our discussions as a research team. The views expressed in this Article are my own, however, and not those of Jean, Kristin, or Future of Music Coalition. My thanks to Ken Ayotte, Scott Baker, Shari Diamond, Zev Eigen, Josh Fischman, Ezra Friedman, William Hubbard, Jessica Litman, Anup Malani, Mark McKenna, Tom Miles, Max Schanzenbach, and Avishalom Tor for helpful comments and advice. -

Scale Agreement Between

Scale Agreement between and October 1, 2015 to September 30, 2020 NFB – CFM SCALE AGREEMENT Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .............................................................................................. 1 RECOGNITION ....................................................................................................... 4 1. SCOPE ........................................................................................................... 4 2. DEFINITIONS ................................................................................................. 4 3. APPLICABLE FEES....................................................................................... 5 4. PENSION FUND ............................................................................................. 5 5. MEMBERSHIP ............................................................................................... 5 6. TEMPORARY MEMBER PERMITS ............................................................... 6 7. TELEVISION CLIPS OR FILLERS ................................................................. 7 8. LICENCE FEES .............................................................................................. 7 9. SCORING IN CANADA .................................................................................. 7 10. CONDITIONS AND FEES .............................................................................. 7 11. WORK DUES DEDUCTIONS ......................................................................... 8 12. CONTRACTS ................................................................................................ -

10 Chapter 2

10 Chapter 2 Answer 2.3 The ER diagram is shown in Figure 2.1. Exercise 2.4 A company database needs to store information about employees (iden- tified by ssn,withsalary and phone as attributes), departments (identified by dno, with dname and budget as attributes), and children of employees (with name and age as attributes). Employees work in departments; each department is managed by an employee; a child must be identified uniquely by name when the parent (who is an employee; assume that only one parent works for the company) is known. We are not interested in information about a child once the parent leaves the company. Draw an ER diagram that captures this information. Answer 2.4 Answer omitted. Exercise 2.5 Notown Records has decided to store information about musicians who perform on its albums (as well as other company data) in a database. The company has wisely chosen to hire you as a database designer (at your usual consulting fee of $2500/day). Each musician that records at Notown has an SSN, a name, an address, and a phone number. Poorly paid musicians often share the same address, and no address has more than one phone. Each instrument used in songs recorded at Notown has a unique identification number, a name (e.g., guitar, synthesizer, flute) and a musical key (e.g., C, B-flat, E-flat). Each album recorded on the Notown label has a unique identification number, a title, a copyright date, a format (e.g., CD or MC), and an album identifier. Each song recorded at Notown has a title and an author. -

The Compositional Influence of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart on Ludwig Van Beethoven’S Early Period Works

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2018 Apr 18th, 12:30 PM - 1:45 PM The Compositional Influence of olfW gang Amadeus Mozart on Ludwig van Beethoven’s Early Period Works Mary L. Krebs Clackamas High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the Musicology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Krebs, Mary L., "The Compositional Influence of olfW gang Amadeus Mozart on Ludwig van Beethoven’s Early Period Works" (2018). Young Historians Conference. 7. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2018/oralpres/7 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. THE COMPOSITIONAL INFLUENCE OF WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART ON LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN’S EARLY PERIOD WORKS Mary Krebs Honors Western Civilization Humanities March 19, 2018 1 Imagine having the opportunity to spend a couple years with your favorite celebrity, only to meet them once and then receiving a phone call from a relative saying your mother was about to die. You would be devastated, being prevented from spending time with your idol because you needed to go care for your sick and dying mother; it would feel as if both your dream and your reality were shattered. This is the exact situation the pianist Ludwig van Beethoven found himself in when he traveled to Vienna in hopes of receiving lessons from his role model, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. -

Beethoven's Eroica Sketches: a Form-Functional Approach

Thomas W. Posen Dissertation Prospectus. Approved Winter 2020 McGill University Beethoven’s Eroica Sketches: A Form-Functional Approach Introduction, Methodology, and Contributions This dissertation introduces new insights into Beethoven’s compositional process to his third symphony. It accomplishes this aim by reconstructing the transcribed single-line sketches to the Eroica found in the Eroica Sketchbook (Beethoven, Lockwood, and Gosman 2013), and by analyzing the reconstructed sketches with form-functional theory (Caplin 1998; 2013). More broadly, this study reorients the analyst’s perspective by valorizing the sketches instead of critiquing them. Form-function theory provides an ideal framework for finding and understanding the strengths in the sketches for three primary reasons.1 First, it prioritizes the role of local harmonic progressions as a determinant of form. We can realize the harmonies that Beethoven implies in his single-line sketches with a high degree of objective accuracy. By contrast, other musical parameters such as texture, dynamics, or instrumentation, which are vital criteria for other well-defined sonata theories (e.g., Hepokoski and Darcy 2011), are very sparse in the sketches and therefore difficult to reconstruct without substantial subjective interpretations. Second, form-function theory minimizes motivic content as the basis of formal function. This feature is important for describing how Beethoven uses the same musical material for different formal functions in successive drafts, and conversely, how he preserves particular formal functions while changing their musical content. Third, the theory establishes well- defined formal categories that can be applied flexibly at all levels of analysis of the sketches (Caplin 1998, 4). These strictly defined categories enable an analyst to elucidate Beethoven’s formal and phrase- structural strategies in individual sketches and compare them across drafts with firm theoretical foundations in an aesthetically neutral environment. -

The-DIY-Musician's-Starter-Guide.Pdf

Table of Contents Introduction 1 - 2 Music Copyright Basics 3 Compositions vs. Sound Recordings 4 - 5 Being Your Own Record Label 6 Being Your Own Music Publisher 7 Wearing Multiple Hats: Being Four Income Participants 8 - 12 Asserting Your Rights and Collecting Your Royalties 13 - 18 Conclusion 19 Legal Notice: This guide is solely for general informational purposes and does not constitute legal or other professional advice. © 2017 TuneRegistry, LLC. All Rights Reserved. 0 Introduction A DIY musician is a musician who takes a “Do-It-Yourself” approach to building a music career. That is, a DIY musician must literally do everything themselves. A DIY musician might have a small network of friends, family, collaborators, and acquaintances that assists them with tasks from time to time. However, virtually all decisions, all failures, and all successes are a result of the DIY musician’s capabilities and efforts. Being a DIY musician can be overwhelming. A DIY musician has a lot on their plate including: writing, recording, promoting, releasing, and monetizing new music; planning, marketing, and producing tours; reaching, building, and engaging a fan base; managing social media; securing publicity; and so much more. A DIY musician may hire a manager and/or attorney to assist them with their career, but they are not signed to or backed by a record label or a music publishing company. Just three decades ago it was virtually impossible for the average DIY musician to get their music widely distributed without the help of a record company. While some DIY musicians were successful in releasing music locally and developing local fan bases, widespread distribution and reach was hard to achieve. -

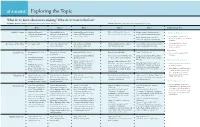

Exploring the Topic

AT A GLANCE Exploring the Topic What do we know about music making? What do we want to find out? Vocabulary—English: instrument, instrumental, sound, accompaniment, homemade Spanish: instrumento, instrumental, sonido, acompañamiento, casero Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Day 4 Day 5 Make Time for… Interest Areas Music and Movement: Music and Movement: Music and Movement: listening Music and Movement: collection of Library: pictures of instruments and Outdoor Experiences collection of homemade and collection of homemade and station with CDs representing a homemade and standard instruments people engaged in musical experiences standard instruments standard instruments; chart variety of musical styles • Invite children to walk around Music and Movement: collection of paper and markers the school or outdoor area and listen homemade and standard instruments for music. • Encourage children to think Question of the Day Do you like to sing? Did you hear music on your Can we make a sound with Which instrument would you like to Do you think you can use these to make of ways to make music with way to school today? these? (objects such as keys, play? (offer three choices) music? (a comb and two spoons) outdoor materials. spoons, etc.) Physical Fun Movement: Movement: Movement: Movement: Song: Large Group Bounce, Bounce, The Kids Go My Body Jumps Let’s All Follow “Old MacDonald” • Intentional Teaching Card P21, Bounce Marching In Discussion and Shared Writing: Discussion and Shared Writing: What Discussion and Shared Writing: What “Hopping” Discussion and Shared -

Understanding Music Past and Present

Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Dahlonega, GA Understanding Music: Past and Present is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This license allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work, even commercially, as long as you credit this original source for the creation and license the new creation under identical terms. If you reuse this content elsewhere, in order to comply with the attribution requirements of the license please attribute the original source to the University System of Georgia. NOTE: The above copyright license which University System of Georgia uses for their original content does not extend to or include content which was accessed and incorpo- rated, and which is licensed under various other CC Licenses, such as ND licenses. Nor does it extend to or include any Special Permissions which were granted to us by the rightsholders for our use of their content. Image Disclaimer: All images and figures in this book are believed to be (after a rea- sonable investigation) either public domain or carry a compatible Creative Commons license. If you are the copyright owner of images in this book and you have not authorized the use of your work under these terms, please contact the University of North Georgia Press at [email protected] to have the content removed. ISBN: 978-1-940771-33-5 Produced by: University System of Georgia Published by: University of North Georgia Press Dahlonega, Georgia Cover Design and Layout Design: Corey Parson For more information, please visit http://ung.edu/university-press Or email [email protected] TABLE OF C ONTENTS MUSIC FUNDAMENTALS 1 N. -

EXPLORING MUSIC with Bill Mcglaughlin Broadcast Schedule – Winter 2020

EXPLORING MUSIC with Bill McGlaughlin Broadcast Schedule – Winter 2020 PROGRAM #: EXP 20-14 RELEASE: Week of January 6, 2020 Beethoven and the Piano Beethoven and the Piano – 200 years after the composition of Beethoven’s five Piano Concertos, they’re still the giants of the piano world. Join us for a concerto a day, plus some of his more intimate works for the instrument. Leon Fleisher, Murray Perahia, and Martha Argerich are a few of the prominent pianist that we will hear from this week. PROGRAM #: EXP 20-15 RELEASE: Week of January 13, 2020 André Previn: German born American composer, conductor, and pianist (1929-2019) By age 20, Andre Previn was successfully composing for Hollywood and playing the piano in Jazz clubs. Soon after winning one of his many Academy Awards, for “My Fair Lady”, Previn released a highly acclaimed jazz album based on the popular songs from this Oscar winning movie. In the 1960s, at the top of his jazz and film composing career, he transformed his profession to include classical music. Previn is known for his open approach to blending the musical worlds of classical, pop, film, theater, and jazz. This week we will listen to recordings from his long career with the London Symphony, hear his brilliant piano playing, his film scores, and sample an aria or two from one of his operas. PROGRAM #: EXP 20-16 RELEASE: Week of January 20, 2020 Claude Debussy Claude Debussy, who once said he learned more from poets and painters than from the music conservatory, is considered the figurehead of Impressionist music (though he would vehemently argue against it). -

Introduction to Music Technology

PUBLIC SCHOOLS OF EDISON TOWNSHIP DIVISION OF CURRICULUM AND INSTRUCTION INTRODUCTION TO MUSIC TECHNOLOGY Length of Course: Semester (Full Year) Elective / Required: Elective Schools: High Schools Student Eligibility: Grade 9-12 Credit Value: 5 credits Date Approved: September 24, 2012 Introduction to Music Technology TABLE OF CONTENTS Statement of Purpose ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 Introduction ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 Course Objectives ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 Unit 1: Introduction to Music Technology Course and Lab ------------------------------------9 Unit 2: Legal and Ethical Issues In Digital Music -----------------------------------------------11 Unit 3: Basic Projects: Mash-ups and Podcasts ------------------------------------------------13 Unit 4: The Science of Sound & Sound Transmission ----------------------------------------14 Unit 5: Sound Reproduction – From Edison to MP3 ------------------------------------------16 Unit 6: Electronic Composition – Tools For The Musician -----------------------------------18 Unit 7: Pro Tools ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------20 Unit 8: Matching Sight to Sound: Video & Film -------------------------------------------------22 APPENDICES A Performance Assessments B Course Texts and Supplemental Materials C Technology/Website References D Arts -

Show Design and Wind Arranging for Marching Ensembles

Show Design and Wind Arranging for Marching Ensembles Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By John Michael Brennan, B.M.E. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2014 Thesis Committee: Professor Daryl W. Kinney, Advisor Professor Timothy Gerber Professor Thomas Wells Director Jonathan Waters Copyrighted by John Michael Brennan 2014 Abstract The purpose this study is to illustrate current trends in show design and wind arranging within the marching band and drum corps activity. Through a comprehensive review of literature a need for further study on this subject was discovered. Specifically, texts from the 1950s, 60s, and 70s focused primarily on marching band arranging practices with minimal influence of show design. Since the 1980s, several documents have been written that discuss show design with some degree of detail, but have neglected to thoroughly address changes in marching band arranging. It is the aim of this thesis to discuss current trends and techniques in marching band wind arranging, and the higher level of detail placed into show conceptualization used by drum corps, competitive, and show band. ii Dedication To Rachael, the most patient, loving, and caring wife a husband could ever ask for. To my daughter Ellie Ann, who I cannot wait to meet in the coming weeks. iii Acknowledgements First and foremost, my family has helped me immensely both in my personal and professional life. It is without their support, witty commentary (especially from my brother’s), and encouragement that I have been able to work in a field I am passionate about. -

CALIFORNIA STATE POLYTECHNIC UNIVERSITY, POMONA MU4171 Theory, History, and Design of Musical Instruments Expanded Course Outline

CALIFORNIA STATE POLYTECHNIC UNIVERSITY, POMONA MU4171 Theory, History, and Design of Musical Instruments Expanded Course Outline Course Subject Area: MU Course Number: 4171 Course Title: Theory, History, and Design of Musical Instruments Units: 3 C/S Classification #: C-04 Component: Lecture Grading Basis: (graded only, CR/NC only, student’s Graded only choice) Repeat Basis: (may be taken once, taken multiple times, Taken once taken multiple times only with different topics) Cross Listed Course: (if offered with another department) NO Dual Listed Course: (if offered as lower/upper division or NO undergraduate/graduate) Major course/Service course/GE Course: (pick all that GE Course apply) General Education Area/Subarea: (as appropriate) C-4 Date Prepared: 10.29.15 Prepared by: Dr. Jessie M. Vallejo I. Catalog Description Theory, History, and Design of Musical Instruments (3) A modern interpretation of organology, or the study and classification of musical instruments. Students will explore sound production by classifying and analyzing musical instruments. The class will also examine diverse concepts of musical instruments as tools or beings. All students will be required to design and build a prototype of a new instrument or adaptation of an already existing instrument. 3 lectures/discussion. Course fulfills GE C-4, B-5, or D-4. II. Required Coursework and Background Complete GE requirements for area A, C-1, C-2, C-3, and lower divisions for at least B, C, or D. III. Expected Outcomes A. Class Outcomes 1. Students will be able to evaluate and analyze how sound is produced by musical instruments according to several classification systems, such as Hornbostel-Sachs.