PIMS 751 SWEDPRA Terminal Evaluation Report- FINAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Korea 8 Tourism & Investment

UNDERSTANDING KOREA 8 TOURISM & INVESTMENT PYONGYANG, KOREA Juche 106 (2017) UNDERSTANDING KOREA 8 TOURISM & INVESTMENT Foreign Languages Publishing House Pyongyang, Korea Juche 106 (2017) CONTENTS 1. Tourism Resources.................................................1 2. Major Tourist Attractions .......................................1 3. Pyongyang, a Tourist Destination...........................2 4. Monumental Structures in Pyongyang....................2 5. Grand Monument on Mansu Hill............................2 6. Tower of the Juche Idea..........................................3 7. Monument to Party Founding .................................4 8. Chollima Statue.......................................................5 9. Arch of Triumph .....................................................6 10. Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum and Monument to the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War ....................7 11. Monument to the Three Charters for National Reunification......................................8 12. Parks and Pleasure Grounds in Pyongyang.............9 13. Moran Hill ............................................................10 14. Kaeson Youth Park ...............................................10 15. Rungna People’s Pleasure Ground........................11 16. Pyongyang, a Time-Honoured City ......................12 17. Royal Tombs in Pyongyang..................................13 18. Mausoleum of King Tangun................................. 13 19. Mausoleum of King Tongmyong.......................... 14 20. -

CBD Strategy and Action Plan

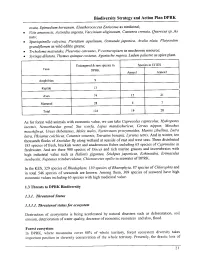

Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan DPRK ovata, Epimedium koreanum, Eleutherococcus Enticosus as medicinal; · Vitis amurensis, Actinidia argenta, Vaccinium uliginosum, Castanea crenata, Querecus sp._As nuts; · Spuriopinella calycina, Pteridium aquilinum, Osmunda japonica, Aralia elata, Platycodon grandifiorum as wild edible greens; · Trcholoma matsutake, 'Pleurotus ostreatus, P. cornucopiaen as mushroom resource; · Syringa dilatata, Thylgus quinque costatus, Agastache rugosa, Ledum palustre as spice plant. Endangered & rare species in Species inCITES Taxa DPRK Annexl Annex2 . Amphibian 9 Reptile 13 Aves 74 15 2 I Mammal 28 4 7 Total 124 19 28 As for forest wild animals with economic value, we can take Caprecolus caprecolus, Hydropotes inermis, Nemorhaedus goral, Sus scorfa, Lepus mandschuricus, Cervus nippon, Moschus moschiferus, Ursus thibetatnus, Meles meles, Nyctereutes procyonoides, Martes zibellina, Lutra lutra, Phsianus colchicus, Coturnix xoturnix, Tetrastes bonasia, Lyrurus tetrix. And in winter, ten thousands flocks of Anatidae fly along wetland at seaside of east and west seas. There distributed 185 species of fresh, brackish water and anadromous fishes including 65 species of Cyprinidae in freshwater. And are there 900 species of Disces and rich marine grasses and invertebrates with high industrial value such as Haliotis gigantea, Stichpus japonicus, Echinoidea, Erimaculus isenbeckii, Neptunus trituberculatus, Chionoecetes opilio in seawater of DPRK. In the KES, 329 species of Rhodophyta, 130 species of Rhaeophyta, 87 species of Chlorophta and in total 546 species of seaweeds are known. Among them, 309 species of seaweed have high economic values including 63 species with high medicinal value. 1.3 Threats to DPRK Biodiversity 1.3. L Threatened Status 1.3.1.1. Threatened status for ecosystem Destruction of ecosystems is being accelerated by natural disasters such as deforestation, soil erosion, deterioration of water quality, decrease of economic resources and also, flood. -

DPRK) So Far This Year

DEMOCRATIC PEOPLE’S 16 April 2004 REPUBLIC OF KOREA Appeal No. 01.68/2004 Appeal Target: CHF 14, 278, 310 Programme Update No. 01 Period covered: January – March 2004 The Federation’s mission is to improve the lives of vulnerable people by mobilising the power of humanity. It is the world’s largest humanitarian organisation and its millions of volunteers are active in over 180 countries. For more information: www.ifrc.org In Brief Appeal coverage: 36.3 %; See attached Contributions List for details. Outstanding needs: CHF 9,089,504 Related Emergency or Annual Appeals: 01.67/2003 Programme Summary: No major natural disasters have affected the People’s Democratic Republic of Korea (DPRK) so far this year. Food security is a major concern, especially in areas remote from the capital. The Red Cross Society of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK RC) has been granted permission from the government to expand the Federation supported health and care programme to another province, increasing the number of potential beneficiaries covered by the essential medicines programme to 8.8 million from July 2004. Due to delayed funding, the first quarter of 2004 has been used to finalise most of the programme activities from the 2003 appeal. Bilateral support from the Republic of Korea, the Netherlands and the Norwegian Red Cross Societies is supplementing Federation support. Partner national societies renewed their commitment to continue supporting DPRK RC. DPRK RC is regarded as an important organisation in DPRK by the government, donor country embassies, UN agencies and NGOs. Operational developments Harvests last year in DPRK were above average, however, the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) and the World Food Programme (WFP) state that, despite the good harvests, the situation remains “especially precarious” for young children, pregnant and nursing women and many elderly people. -

Korea-Today-2021-0306.Pdf

Monthly Journal (777) C O N T E N T S 2 Second Plenary Meeting of Eighth Central Committee of WPK Held 12 Kim Jong Un Sees Lunar New Year’s Day Performance with Party Central Leadership Body Members 14 Appeal to All Working People Across the Country 15 By Dint of Scientifi c Self-reliance 16 Harnessing of Renewable Energy Propelled 17 Electric Power Management Gets Upgraded 18 By Tapping Local Materials 19 Secret of Increasing Production 20 Ideals for New Victory 21 Guidance for the People’s Well-being Monthly journal Korea Today is available on the Internet site www.korean-books.com.kp in English, Russian and Chinese. 22 Education Highlighted in DPRK 23 Immortal Juche Idea (10) Self-reliance in National Defence 24 Pride of Medical Scientist 24 Authority on Burns Treatment 26 With Sincerity and Devotion 28 True story Front Cover: On March Life and Promise 8 International Women’s Day 30 Vinalon Inventor and His Descendants Photo by courtesy 32 E-commerce Gets Expansive of the KCNA 33 Efforts for Correct and Prompt Weather Forecast 34 How Mun Has Overcome Disability 35 Liquefi ed Rare Earth Draws Attention 36 Small Institute in Woods 37 People Who Strive to Increase Forest Land 38 Songchon County Changes 40 Pacesetter of Costume Culture 41 For Conservation of Water Resources 42 Kimchi, Distinctive Dish of Korea (1) Kimchi and Folklore of Korea 44 Mt Chilbo ( 2 ) Back Cover: Rhododen- 46 National Intangible Cultural Heritage (51) dron blossoms in the snow Ssolmaethagi Photo by Song Tae Hyok 47 Ho Jun and Tonguibogam 48 History Denounces 13502 Edited by An Su Yong Address: Sochon-dong, Sosong District, Pyongyang, DPRK E-mail: fl [email protected] © The Foreign Language Magazines 2021 1 ► amine the plans for this year in detail and fi x and work for implementing the decisions made at the issue them as the decisions of the Party Central Party congress starts and what kind of change is Committee. -

January 1982–May 1983

KIM IL SUNG WORKS WORKING PEOPLE OF THE WHOLE WORLD, UNITE! KIM IL SUNG WORKS 37 January 1982–May 1983 FOREIGN LANGUAGES PUBLISHING HOUSE PYONGYANG, KOREA 1 9 9 1 CONTENTS NEW YEAR ADDRESS January 1, 1982 ......................................................................................................................1 ON IMPROVING THE QUALITY OF REFRACTORIES Speech at a Consultative Meeting of the Senior Officials of the Administration Council, January 27, 1982................................................................10 ON SOME TASKS FACING THE CHEMICAL INDUSTRY Speech Delivered at a Consultative Meeting of the Senior Officials of the Chemical Industry, February 9, 1982.........................................................20 ON CONDUCTING SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNOLOGICAL RESEARCH IN KEEPING WITH THE SITUATION IN OUR COUNTRY Speech at the Consultative Meeting of Officials in the Field of Science and Technology, February 17, 1982..................................................................30 ON SOME TASKS IN DEVELOPING SEAFOOD PRODUCTION Speech at an Enlarged Meeting of the Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the Workers’ Party of Korea, February 18, 1982.........................................46 OPEN LETTER TO ALL VOTERS THROUGHOUT THE COUNTRY February 19, 1982 ................................................................................................................68 ON THE ADMINISTRATION COUNCIL’S ORIENTATION OF ACTIVITIES Speech at the First Plenary Meeting of the Administration Council of the Democratic -

Most of Korea's

Gold Medal of Yesenin Chairman Kim Jong Il received Gold Medal of Yesenin from the Moscow Committee of the Union of Russian Authors and Editorial Board of Moscoviya Literaturnaya in March 2008. Monthly Journal (753) C O N T E N T S 3 Into “Gold Mountains,” “Treasure Mountains” In Korea there is under way a vigorous all-people drive for afforestation and conservation of forests. 5 Forest Resources Increase 8 Forest Designers 10 Efforts Go into Afforestation 12 Planting Trees Personally 13 Product of Growing Demand 14 Makers of Pine Brand Backpacks 16 Light-burned Magnesia Products Grow Popular 18 Talented Young Scientists 20 For Underground Resources Development Monthly journal Korea Today is printed and posted on the Internet site www.korean-books.com.kp in English, Russian and Chinese. 1 21 High Aim to Beat World 22 Using New Teaching Methods 24 Worthwhile 26 Under Free Medical Care 27 Songyo Koryo Medicine Factory 28 Star of Gymnastics 28 National Intangible Cultural Heritage (28) Koryo Medicinal Dietary Therapy Front Cover: Saplings are tended well at the Mun- 30 Motive Force for Victory dok County Forest Man- agement Station in South 32 Believe in Yourself Phyongan Province 34 Women’s Profi le Photo by Ra Phyong Ryol 36 Patriotic Family 37 Changing Scenery of Taedong River 40 White Herons Fly over Land of Sangwon 41 Country Rich in Mineral Water 42 Mt Kumgang (1) 44 Myongnimdabbu, a Hundred-year-old Veteran Commander 45 To Usher in Heyday of Peace, Prosperity and Reunifi cation 46 Demonstration of Ardent Patriotic Spirit 48 Japan’s Old -

Setting Devotion to People at Core of WPK's Activities

Democratic People’s Republic of Korea No. 32 (3 172) weekly http://www.pyongyangtimes.com.kp e-mail:[email protected] Sat, August 7, Juche 110 (2021) LEAD PATRIOT Setting devotion to people at Nation blessed with core of WPK’s activities growing number of patriots Meritorious persons of Kim Jong Il made sure that It is the supreme principle of always went deeper among the day in August 2018, saying he socialist patriotism are found the people across the country activities of the Workers’ Party people to become their firm would only feel at ease when everywhere in the DPRK which learned after the spiritual world of Korea to steadily improve the spiritual pillar and share weal he rode it first, and examined is seething with enthusiasm of Hero Jong Song Ok and, at people’s material and cultural and woe near them and devoted handles and other fittings one for implementing the first-year the same time, put forward standards of living. everything for their wellbeing by one. tasks of the new five-year plan. frontrunners in various fields as The Third Plenary Meeting of whenever they were in trouble. When new streets and leisure They are unassumingly leaving heroes of the times. the Eighth Central Committee One day in September facilities such as Changjon, indelible marks of their life The Korean people cultivated of the WPK held last June 2020 when the General Mirae Scientists and Ryomyong in the building of a thriving their minds in the days of severe discussed as its major agenda Secretary inspected Kangbuk- streets and the Munsu Water country with their intense trials as they learned the noble items the issues of protecting ri of Kumchon County, North Park were under construction, loyalty, clean conscience and spirit of the chairwoman of the the life and safety of the people, Hwanghae Province, which was he visited the construction sites untiring devotion and passion. -

Democratic People's Republic of Korea

DEMOCRATIC PEOPLE’S 11 December 2004 REPUBLIC OF KOREA The Federation’s mission is to improve the lives of vulnerable people by mobilising the power of humanity. It is the world’s largest humanitarian organisation and its millions of volunteers are active in over 181 countries. For more information: www.ifrc.org In Brief Appeal No. 01.68/2004; Programme Update no. 03, Period covered: July to September 2004; Appeal coverage: 71.7%; Outstanding needs: CHF 4,040,761.73 (USD 3,481,615 or EUR 2,634,394). (click here to go directly to the attached Contributions List (also available on the website). Appeal target: CHF 14,278,310 (USD 12,302,525 or EUR 9,308,811) Related Emergency or Annual Appeals: Appeal 2004 (01.68/04) Programme summary: This programme update covers the third quarter of 2004, reporting on the progress made by the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) Red Cross and the Federation during the months of July, August and September. The DPRK Red Cross and the Federation’s health and care, water and sanitation, disaster management and organisational development (OD) programmes are more or less progressing according to plan. Several review teams were in DPRK over the reporting period to measure progress made in the DPRK Red Cross activities, and results from these visits for the most part were quite positive. Although progress in meeting the expected results for the OD programme is slightly behind target, the distribution of health kits to medical institutions will surpass the original appeal target because of an in-kind donation. -

Democratic People's Republic of Korea

Operational Environment & Threat Analysis Volume 10, Issue 1 January - March 2019 Democratic People’s Republic of Korea APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE; DISTRIBUTION IS UNLIMITED OEE Red Diamond published by TRADOC G-2 Operational INSIDE THIS ISSUE Environment & Threat Analysis Directorate, Fort Leavenworth, KS Topic Inquiries: Democratic People’s Republic of Korea: Angela Williams (DAC), Branch Chief, Training & Support The Hermit Kingdom .............................................. 3 Jennifer Dunn (DAC), Branch Chief, Analysis & Production OE&TA Staff: North Korea Penny Mellies (DAC) Director, OE&TA Threat Actor Overview ......................................... 11 [email protected] 913-684-7920 MAJ Megan Williams MP LO Jangmadang: Development of a Black [email protected] 913-684-7944 Market-Driven Economy ...................................... 14 WO2 Rob Whalley UK LO [email protected] 913-684-7994 The Nature of The Kim Family Regime: Paula Devers (DAC) Intelligence Specialist The Guerrilla Dynasty and Gulag State .................. 18 [email protected] 913-684-7907 Laura Deatrick (CTR) Editor Challenges to Engaging North Korea’s [email protected] 913-684-7925 Keith French (CTR) Geospatial Analyst Population through Information Operations .......... 23 [email protected] 913-684-7953 North Korea’s Methods to Counter Angela Williams (DAC) Branch Chief, T&S Enemy Wet Gap Crossings .................................... 26 [email protected] 913-684-7929 John Dalbey (CTR) Military Analyst Summary of “Assessment to Collapse in [email protected] 913-684-7939 TM the DPRK: A NSI Pathways Report” ..................... 28 Jerry England (DAC) Intelligence Specialist [email protected] 913-684-7934 Previous North Korean Red Rick Garcia (CTR) Military Analyst Diamond articles ................................................ -

2017 Annual Report the Red Cross Society of The

2017 Annual Report The Red Cross Society of the Democratic People‟s Republic of Korea January 2018 1 Contents Introduction Analysis of the situation SWOT analysis – external threats and opportunities SWOT analysis – internal strengths and weaknesses Stakeholder analysis Achievements of Strategic Goals Annex1: Achievements of programme goals Annex 2: Partners‟ commitments discussed in CAS meeting, September 2017 Fundamental Principles of RCRC Movement 2 1. I ntrodu cti on The Red Cross Society of Democratic People‟s Republic of Korea, founded on October 18, 1946 was admitted to the IFRC on May 11, 1956. The following figures reflect the human resource and the branch network of the society by the end of 2017. The total number of RC members is 1,079,934; among them adult members are 723,563; volunteers 105,609 and youth members 356,371. The headquarters is in Pyongyang with 17 permanent branches (of provincial/city level) and 192 non-permanent branches (of county level). The society has gon through two stages of institutional changes in 2000s and consistently building its capacity following the developing situation to complete its mission and the role as the leading humanitarian organization in the country. By the special attention to strengthen the legal basis of the society, the Law of the DPRK RCS was adopted in January 2007 and the revised statutes of the society was adopted in 2016 during the National Congress, the statutory gathering holding every four years. Upholding the organizational development and the capacity building as its most priority tasks, the society separated the roles and responsibilities of the governance from the management in 2004, revised the organizational structure into the one of specialization from the headquarters down to the branches, improved the specialization level by providing appropriate human resource and building their capacity in order to fulfill its role as the auxiliary to the government in the humanitarian field. -

Annual Report of the Red Cross Society of Democratic People's

Annual Report of the Red Cross Society of Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (2016) Mission The mission of the Red Cross Society of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK RCS) is to prevent and alleviate human sufferings and misfortunes without any discrimination and to improve their health and welfare, promoting the friendship, solidarity and cooperation among peoples, thus contributing to maintenance of world peace. DPRK RCS activities in 2016 to implement the objectives of the NS strategic plan 2016 1. Save lives, protect livelihoods and strengthen recovery from different disasters and crises by enhancing disaster preparedness and emergency response capacity, focusing on disaster prevention and mitigation. (2016 strategic aim 1) Community-Based Disaster Risk Reduction Project Activities DPRK Red Cross Society has greatly contributed to building safe and resilient communities through the activities to reduce the disaster risks such as flood, landslide, typhoon, tidal wave and mountain fire, and improving livelihood of people in over 50 disaster-prone communities. In close collaboration with the local authorities and scientific institutions, DPRK RCS branches of all levels have conducted several disaster risk reduction (DRR) activities to prevent natural disasters and improve the technical skills of the field staff. DPRK RCS, in cooperation with Ministry of Land and Environment Protection (MoLEP) and the Academy of Forestry, actively supported tree seedling production of city/county mother tree nurseries and tree planting in RC targeted communities and neighbouring areas, thus contributed to preventing forest denudation, main cause of disasters, and conserving the soil. With the technical support of engineers and technicians from MoLEP, DPRK RCS organized the technical trainings for 200 tree nursery staff and forest rangers to improve their knowledge and practice on construction and management of tree nursery and tree seedling production. -

Climate Change Outlook Democratic People’S Republic of Korea Environment and Climate Change Outlook

Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Environment and Climate Change Outlook Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Environment and Climate Change Outlook Pyongyang 2012 Democratic People’s Republic of Korea Environment and Climate Change Outlook Copyright © 2012, Ministry of Land and Environment Protection, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea ISBN: 978-9946-1-0170-5 This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the Ministry of Land and Environment Protection, DPR of Korea. DISCLAIMER The contents and views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies, or carry the endorsement of the contributory organizations or the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expressions of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the contributory organizations or UNEP concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Data and information contained in this report were provided by agencies and experts from the DPR of Korea and other sources. Although UNEP has provided technical assistance in the preparation of the report, it is not responsible for the contents of the report and does not warrant the accuracy, adequacy or completeness of the data and information.