The History and Politics of Second Amendment Scholarship: a Primer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Joyce Foundation Betraying Donor Intent in the Windy City

Stopping Juvenile Detention: The Joyce Foundation Betraying donor intent in the Windy City By Jonathan Hanen Summary : The Joyce Foundation’s en- dowment came from David Joyce, a lum- ber magnate who believed in the American system of free enterprise. Today the foun- dation that lives off his wealth is a hotbed of trendy, left-wing thinking and grant- making. It funds efforts to hurt the lumber industry, turn schools into union-controlled sources of Democratic Party patronage, block Americans’ gun rights, and constrict economic freedoms. Barack Obama sat on its board from 1994 to 2002, and directed the foundation’s money to causes Joyce al- most certainly would not have favored. he Joyce Foundation, based in Chicago, Illinois, was founded in T1948 by Beatrice Joyce Kean, the Leftist Ellen Alberding runs the Joyce Foundation. sole heir to the Joyce family fortune. The Joyces of Clinton, Iowa, originally made by the end of his life he was “a stockholder gave him the ownership of several plants.” their money in the lumber industry. The in twelve different sawmill plants located Joyce was “prominent in public enterprises patriarch who created the Joyce fortune was in all sections of the country, one within and contributed large amounts to various the great nineteenth-century entrepreneur eighteen miles of Lake Superior at the North religious institutions and was a subscriber David Joyce (died 1904). Of “old New and another within eighty miles of the Gulf to society and educational work.” England Puritan stock,” he was “strong, of Mexico in the South, while still another bold and resourceful.” “He was one of the was on Puget Sound.” “Mr. -

NACBS NECBS Program, Boston Cambridge, 1999

NACBS/NECBS Program, Boston/Cambridge, 1999 file:///Macintosh%20HD/Users/jaskelly/Desktop/temp.html THE NORTH AMERICAN CONFERENCE ON BRITISH STUDIES in conjunction with THE NORTHEAST CONFERENCE ON BRITISH STUDIES ANNUAL MEETING 19-21 November 1999 Royal Sonesta Hotel Cambridge, Massachusetts NACBS Council President 1 of 29 11/12/08 4:06 PM NACBS/NECBS Program, Boston/Cambridge, 1999 file:///Macintosh%20HD/Users/jaskelly/Desktop/temp.html Fred M. Leventhal (Boston University) Vice President Linda Levy Peck (George Washington University) Immediate Past President Walter L. Arnstein (University of Illinois) Executive Secretary Brian P. Levack (University of Texas, Austin) Associate Executive Secretary Patty Seleski (California State University, San Marcos) Treasurer Marc Baer (Hope College) Program Chair Chris Waters (Williams College) Elected Council Members James Cronin (Boston College) James Epstein (Vanderbilt University) Barbara J. Harris (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill) Robert Tittler (Concordia University) Margo Todd (Vanderbilt University) NECBS Executive Committee President Susan D. Amussen (The Union Institute) Vice President and Program Chair Peter Weiler (Boston College) Immediate Past President Robert Tittler (Concordia University) Secretary-Treasurer Peter Hansen (Worcester Polytechnic Institute) A NOTE FROM THE PROGRAM CHAIR On behalf of the program committees and officers of the North American Conference on British Studies and the Northeast Conference on British Studies, I would like to welcome you to this year’s joint annual meeting of the two organizations and draw your attention to several special events taking place at the conference. There will be three plenary addresses this year. On Friday, following lunch, Professor Deborah Epstein Nord (Princeton University) will be speaking on ‘Children of Hagar: Gypsy Fascination in 2 of 29 11/12/08 4:06 PM NACBS/NECBS Program, Boston/Cambridge, 1999 file:///Macintosh%20HD/Users/jaskelly/Desktop/temp.html Nineteenth-Century Britain’. -

The Joyce Foundation 2004 Annual Report a Teacher Affects Eternity; He Can Never Tell Where His Influence Stops

The Joyce Foundation 2004 Annual Report A teacher affects eternity; he can never tell where his influence stops. Henry Adams 8 President’s Letter 10 Education 44 Employment 45 Environment 46 Gun Violence 47 Money and Politics 48 Culture 49 Grants Approved 65 Financial Statements 73 2005 Program Guidelines 48 Fifty years after Brown v. Board of Education, America’s schools still fail to provide many poor and minority children with a quality education. 2 3 A big part of the problem: poor and minority children are much more likely than other children to have teachers who are inexperienced, uncertified, or teaching subjects they were not trained to teach. 4 5 Yet hope exists: over time, effective teachers can erase the achievement gap and help kids learn. 6 7 In each of the Foundation’s programs, our priorities are shaped by what the research identifies as the most effective strategies to address social challenges. Our goal is to identify and promote evidence-based public policies that will improve the lives of Midwest citizens. The Foundation’s board has identified six broad categories of issues that have an impact on our region: education, the environment, employment, gun violence, money and politics, and culture. When determining what to fund within these categories, we consider the president’s letter severity of a problem, our ability to identify a possible solution, and the likelihood that our resources can make Among the central challenges facing our nation today is how to provide high-quality education and a difference. The projects that we fund almost always include some of the following: training to the next generation of adults. -

How the Firearms Industry and NRA Market Guns to Communities of Color

JANUARY 2021 How the Firearms Industry and NRA Market Guns to Communities of Color WWW.VPC.ORG COPYRIGHT AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Copyright © January 2021 Violence Policy Center Violence Policy Center 1025 Connecticut Avenue, NW Suite 1210 Washington, DC 20036 202-822-8200 The Violence Policy Center (VPC) is a national nonprofit educational organization that conducts research and public education on violence in America and provides information and analysis to policymakers, journalists, advocates, and the general public. This study was authored by VPC Executive Director Josh Sugarmann. Additional research assistance was provided by Alyssa Berkson, Jacob Gurvis, Nicholas Hannan, Ellie Pasternack, and Jill Rosenfeld. This study was funded with the support of The Joyce Foundation and the Lisa and Douglas Goldman Fund. For a complete list of VPC publications with document links, please visit http://www.vpc.org/publications. To learn more about the Violence Policy Center, or to make a tax-deductible contribution to help support our work, please visit www.vpc.org. 2 | VIOLENCE POLICY CENTER HOW THE FIREARMS INDUSTRY AND NRA MARKET GUNS TO COMMUNITIES OF COLOR TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Section One: The National Shooting Sports Foundation (NSSF) and the Firearms Industry 4 Section Two: The National Rifle Association 20 Section Three: The NSSF and NRA Exploit COVID-19 in Their Marketing Efforts 28 Section Four: The Reality of Black and Latino Americans and Guns 32 Section Five: The Myth of Self-Defense Gun Use 36 Conclusion 38 This study is also available online at: https://vpc.org/how-the-firearms-industry-and-nra-market-guns-to-communities-of-color/. -

The Joyce Foundation Annual Report 2001 President’S Letter 2 Education 6 Employment 10 Environment 14

The Joyce Foundation Annual Report 2001 President’s Letter 2 Education 6 Employment 10 Environment 14 Gun Violence 18 Money and Politics 22 Culture 26 Grants Approved 30 Financial Statements 46 2002 Program Guidelines 54 The Joyce Foundation supports efforts to protect the natural environment of the Great Lakes, to reduce poverty and violence in the region, and to ensure that its people have access to good schools, decent jobs, and a diverse and thriving culture. We are especially interested in improving public policies, because public systems such as education and welfare directly affect the lives of so many people, and because public policies help shape private sector decisions about jobs, the environment, and the health of our communities. To ensure that public policies truly reflect public rather than private interests, we support efforts to reform the system of financing election campaigns. What really matters? What really matters? Saving the life of one When economic progress falters, when people child. The health of the place where we live. lose confidence in fundamental institutions, when A decent education. The capacity to climb out the world seems irrevocably changed by acts of of poverty and into a job. A functioning democ- terrorism, people find themselves asking basic racy. Access to culture, to help us understand, questions about meaning, purpose, and mission. shape, and celebrate our world. These are the As a new leader, but one with a long associa- things that give us hope, in the sense that Vaclav tion with this remarkable Foundation, I begin Havel defines it: “not the same as joy that things my tenure knowing that Joyce has chosen to are going well, or willingness to invest in enter- tackle problems that defy easy solutions. -

Building a Culture of Free Expression on the American College Campus

Building a Culture of Free Expression on the American College Campus CHALLENGES & SOLUTIONS by JOYCE LEE MALCOLM Perspectives on Higher Education American Council of Trustees and Alumni | Institute for Effective Governance™ The American Council of Trustees and Alumni (ACTA) is an independent, nonprofit organization committed to academic freedom, excellence, and accountability at America’s colleges and universities. Founded in 1995, ACTA is the only national organization dedicated to working with alumni, donors, trustees, and education leaders across the United States to support liberal arts education, uphold high academic standards, safeguard the free exchange of ideas on campus, and ensure that the next generation receives an intellectually rich, high-quality education at an affordable price. Our network consists of alumni and trustees from nearly 1,300 colleges and universities, including over 23,000 current board members. Our quarterly newsletter, Inside Academe, reaches more than 13,000 readers. ACTA’s Institute for Effective Governance™ (IEG), founded in 2003 by college and university trustees for trustees, is devoted to enhancing boards’ effectiveness and helping trustees fulfill their fiduciary responsibilities fully and effectively. IEG offers a range of services tailored to the specific needs of individual boards and focuses on academic quality, academic freedom, and accountability. Through its Perspectives on Higher Education essays, the Institute for Effective Governance™ seeks to stimulate discussion of key issues affecting America’s colleges and universities. Building a Culture of Free Expression on the American College Campus n n n CHALLENGES & SOLUTIONS by Joyce Lee Malcolm American Council of Trustees and Alumni Institute for Effective Governance™ April 2018 Building a CULTURE OF FREE EXPRESSION on the American College Campus About the Author Joyce Lee Malcolm is the Patrick Henry Professor of Constitutional Law and the Second Amendment at the Antonin Scalia Law School of George Mason University. -

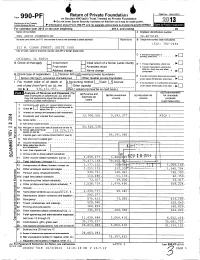

Form 990-PF and Its Separate Instructions Is at Www

Return of Private Foundaticii OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-P F or Section 4947( a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation Do not enter Social Security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury ► 2013 Internal Revenue Service ► Information about Form 990-PF and its separate instructions is at www. frs.gov/form990pf. • For calendar y ear 2013 or tax y ear be g inning , 2013 , and endin g , 20 Name of foundation A Employer identification number THE JOYCE FOUNDATI ON 36-6079185 Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room / suite B Telephone number (see instructions) (312) 782-2464 321 N. CLARK STREET, SUITE 1500 City or town, state or province , country , and ZIP or foreign postal code q C If exemption application is ► pending , check here • . , CHICAGO, IL 60654 all that G Check apply Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1 Foreign organizations, check here . ► Final return Amended return 2 Foreign organizations meeting the Address than a Name than e 85% test check here and attach computation ► H Check type of organization X Section 501 ( c 3 exempt private foundation )..? E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947 ( a )( 1 ) nonexem pt charitable trust Other taxable p rivate foundation under section 507(b )(1)(A) El , check here . ► I Fair market value of all assets at J Accounting method L_J Cash X Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month terminati on Other undersectenhO7(b )(1)lB),theckhere end of year (from Part 11, col (c), line (specify) --- -- ----------------- - . -

Promoting Child Development from Birth in State Early Care and Education Initiatives

Center for Law and Social Policy July 2006 Starting Off Right: Promoting Child Development from Birth in State Early Care and Education Initiatives Rachel Schumacher and Katie Hamm Center for Law and Social Policy Anne Goldstein Zero To Three Joan Lombardi The Children’s Project Acknowledgments This paper was made possible by a grant from the A.L. Mailman Family Foundation, as well as general support from the Annie E. Casey Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the George Gund Foundation, the Joyce Foundation, the Moriah Fund, the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, and the Rockefeller Foundation. We are extremely grateful to the many state policymakers and advocates who took time out of their busy schedules to share their experiences and lessons learned. We also wish to thank our reviewers for their comments and input: Helen Blank, Steffanie Clothier, Gerry Cobb, Harriet Dichter, Barbara Gebhard, Erica Lurie-Hurvitz, Anne Mitchell, Marsha Moore, and Nancy Shier. Special thanks also go to our colleagues at CLASP who provided valuable feedback: Danielle Ewen, Director of Child Care and Early Education; Hannah Matthews, Policy Analyst; and Mark Greenberg, Director of Policy. Patrice Johnson also provided research assistance for this project. While we are grateful to the contributions of our reviewers, the authors are solely responsible for the content of this report. For additional resources, see the Child Care and Early Education page of www.clasp.org. Copyright © 2006 by the Center for Law and Social Policy. All rights reserved. Table of -

Hispanic Victims of Lethal Firearms Violence in the United States

Hispanic Victims of Lethal Firearms Violence in the United States This is not the most recent version of Hispanic Victims of Lethal Firearms Violence in the United States. For the most recent edition, as well as its corresponding press release and links to all prior editions, please visit http://vpc.org/revealing-the-impacts-of-gun-violence/hispanic-homicide- victimization/. Violence Policy Center www.vpc.org JULY 2015 Hispanic Victims of Lethal Firearms Violence in the United States WWW.VPC.ORG HISPANIC VICTIMS OF LETHAL FIREARMS VIOLENCE IN THE UNITED STATES VIOLENCE POLICY CENTER | 1 COPYRIGHT AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Copyright © July 2015 Violence Policy Center The Violence Policy Center (VPC) is a national nonprofit educational organization that conducts research and public education on violence in America and provides information and analysis to policymakers, journalists, advocates, and the general public. This study was funded with the support of The Herb Block Foundation, The California Wellness Foundation, and The Joyce Foundation. This study was authored by VPC Senior Policy Analyst Marty Langley and VPC Executive Director Josh Sugarmann. For a complete list of VPC publications with document links, please visit www.vpc.org/publications/. 2 | VIOLENCE POLICY CENTER HISPANIC VICTIMS OF LETHAL FIREARMS VIOLENCE IN THE UNITED STATES TABLE OF CONTENTS Key Findings and Recommendations .............................................................................................................................................................i -

The Second Amendment Works! the Second “Jim Ostrowski Is One of the Finest People in the Libertarian Movement.” -- Murray N

James Ostrowski Political Science/Law/History The Second Amendment Works! The Second “Jim Ostrowski is one of the finest people in the libertarian movement.” -- Murray N. Rothbard (1926-1995), founder of the modern liberty movement and dean of the Austrian School of Amendment Economics “Ostrowski has developed into something of a modern-day Works! Thomas Paine.” -- The Freeman: Ideas on Liberty (2005) From the book: A Primer on How to Defend Our We need to recognize that gun control is a progressive idea. If we don’t understand what progressivism is, then how can we understand the Most Important Right basis for gun control proposals and refute and defeat them? Because the left controls the terms of the debate, the issue has been framed in such a way that we lose. The true purposes of the Second James Ostrowski Amendment are ignored or obfuscated, and smoke screens and red herrings degrade the debate. Never forget that the gun control movement, the government gun monopoly movement in America is, at best, a dangerous ideological delusion, and at worst, a sinister hoax and conspiracy, a movement that claims to abhor gun violence but which has as its core mission to use guns against peaceful law-abiding people to leave them defenseless against murderers, rapists and dictators. Published by Cazenovia Books The Second Amendment Works! A Primer on How to Defend Our Most Important Right By James Ostrowski PROOF COPY Cazenovia Books Buffalo, New York LibertyMovement.org 2AWNY.com Copyright 2020 By Cazenovia Books All rights reserved. Permission to re-print with attribution for non-commercial, educational purposes is hereby granted. -

Black Homicide Victimization in the United States Violence Policy Center | 1 Copyright and Acknowledgments

MAY 2021 Black Homicide Victimization in the United States An Analysis of 2018 Homicide Data WWW.VPC.ORG BLACK HOMICIDE VICTIMIZATION IN THE UNITED STATES VIOLENCE POLICY CENTER | 1 COPYRIGHT AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Copyright © May 2021 Violence Policy Center The Violence Policy Center (VPC) is a national nonprofit educational organization that conducts research and public education on violence in America and provides information and analysis to policymakers, journalists, advocates, and the general public. This study was funded with the support of The Joyce Foundation. This study was also supported by generous gifts from Christine Armeo, David and Ellen Berman, Nicole Fealey, Michael and Chris Feves, and Olivia Hartsell. This study was authored by VPC Senior Policy Analyst Marty Langley and VPC Executive Director Josh Sugarmann. For a complete list of VPC publications with document links, please visit http://www.vpc.org/publications/. To learn more about the Violence Policy Center, please visit www.vpc.org. To make a tax-deductible contribution to help support our work, please visit https://www.vpc.org/contribute. 2 | VIOLENCE POLICY CENTER BLACK HOMICIDE VICTIMIZATION IN THE UNITED STATES THE EPIDEMIC OF BLACK HOMICIDE VICTIMIZATION The devastation homicide inflicts on Black teens and adults is a national crisis, yet it is all too often ignored outside of affected communities. This study examines the problem of Black homicide victimization at the state level by analyzing unpublished Supplementary Homicide Report (SHR) data for Black homicide victimization submitted to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).1 The information used for this report is for the year 2018 and is the most recent data available. -

1 APRIL M. ZEOLI Curriculum Vitae Contact Information School Of

APRIL M. ZEOLI Curriculum Vitae Contact Information School of Criminal Justice Phone: (517) 353-9554 Michigan State University Fax: (517) 432-1787 Baker Hall Email: [email protected] 655 Auditorium Road, Rm. 526 East Lansing, MI 48824 EDUCATION Ph.D. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore MD Department of Health Policy and Management Concentration in Health and Public Policy Dissertation Title: Effects of Public Policies on Intimate Partner Homicide September 2007 M.P.H. The University of Michigan School of Public Health, Ann Arbor MI Department of Health Management and Policy Interdepartmental Concentration in Reproductive and Women’s Health April 2000 B.A. The University of Michigan College of Literature, Science & Arts, Ann Arbor MI Major in Women’s Studies April 1998 PROFESSIONAL EMPLOYMENT 2015-present Associate Professor. School of Criminal Justice and AgBioResearch, Michigan State University. Undergraduate Education Coordinator. School of Criminal Justice, Michigan State University. Faculty Affiliate. Michigan State University College of Law. 2008-present Core Faculty. Research Consortium on Gender-based Violence, Michigan State University. Core Faculty. Center for Gender in Global Context, Michigan State University. 2008-2015 Assistant Professor. School of Criminal Justice and AgBioResearch, Michigan State University. 2003-2008 Research Assistant. Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Policy and Research. 1 SCHOLARSHIP Grants anD AwarDs 2018-2022. Building research capacity for firearm safety among children. Principal Investigators: Rebecca Cunningham & Marc Zimmerman (FY 2018: $947,355). Subcontract to Michigan State University: $53,728. Investigator: April M. Zeoli. 2018. Case-Control Study: How Do Victims and Suspects of Firearm Violence Compare to Controls? Principal Investigator: Mallory O’Brien.