For the Degree Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lycée Français Charles De Gaulle Damascus, Syria

2013 On Site Review Report 4032.SYR by Wael Samhouri Lycée français Charles de Gaulle Damascus, Syria Architect Ateliers Lion Associés, Dagher, Hanna & Partners Client French Ministry of Foreign Affairs Design 2002 - 2006 Completed 2008 Lycée Français Charles de Gaulle Damascus, Syria I. Introduction The Lycée Français Charles de Gaulle in Damascus, a school that houses 900 students from kindergarten up to baccalaureate level, is a garden-like school with classrooms integrated into an intricate system of courtyards and green patios. The main aim of the design was to set a precedent: a design in full respect of the environment that aspires to sustainability. Consequently it set out to eliminate air conditioning and use only natural ventilation, cooling, light/shadows and so economise also on running costs. The result is a project that fully reflects its aims and translates them into a special architectural language of forms with rhythms of alternating spaces, masses, gardens and a dramatic skyline rendered by the distinct vertical elements of the proposed solar chimneys. II. Contextual Information A. Brief historical background This is not an ordinary school, one that is merely expected to perform its educational functions although with a distinguishing characteristic: doing everything in French within an Arab country. Rather, it is a school with a great deal of symbolism and history attached to it. To illustrate this, suffice to say that this school, begun in 2006, was formally inaugurated by the French President himself. On a 2008 hot September Damascene morning, in the presence of world media, President Nicolas Sarkozy and the Syrian Minister of Education attended the formal opening of the school, in the hope of establishing a new phase of Franco-Syrian educational relations. -

The English Claim to Gothic: Contemporary Approaches to an Age-Old Debate (Under the Direction of DR STEFAAN VAN LIEFFERINGE)

ABSTRACT MARY ELIZABETH BLUME The English Claim to Gothic: Contemporary Approaches to an Age-Old Debate (Under the Direction of DR STEFAAN VAN LIEFFERINGE) The Gothic Revival of the nineteenth century in Europe aroused a debate concerning the origin of a style already six centuries old. Besides the underlying quandary of how to define or identify “Gothic” structures, the Victorian revivalists fought vehemently over the national birthright of the style. Although Gothic has been traditionally acknowledged as having French origins, English revivalists insisted on the autonomy of English Gothic as a distinct and independent style of architecture in origin and development. Surprisingly, nearly two centuries later, the debate over Gothic’s nationality persists, though the nationalistic tug-of-war has given way to the more scholarly contest to uncover the style’s authentic origins. Traditionally, scholarship took structural or formal approaches, which struggled to classify structures into rigidly defined periods of formal development. As the Gothic style did not develop in such a cleanly linear fashion, this practice of retrospective labeling took a second place to cultural approaches that consider the Gothic style as a material manifestation of an overarching conscious Gothic cultural movement. Nevertheless, scholars still frequently look to the Isle-de-France when discussing Gothic’s formal and cultural beginnings. Gothic historians have entered a period of reflection upon the field’s historiography, questioning methodological paradigms. This -

It Is Now Commonplace to Think of Preservation As Part of the State's

It is now commonplace to think of preservation as part of the state’s responsibility to protect the public’s interests and welfare. But what happens when government fails to be a good steward of heritage, or worse, engages in its destruction? Activism, as a soft means of citizen oversight and influence in government, has become a central component of preservation. Victor Hugo shaped the role and the responsibilities of preservation activism through newspaper editorials such as these two calls to arms against “demolishers.” He fearlessly spoke truth to power, publishing scathing accusations of negligence and malfeasance against government bureaucrats and private developers for destroying beautiful historic buildings. The beauty of historic architecture was a public good, belonging to everyone and in need of protection. Hugo was born in Besançon, France, in 1802. His father was a military officer, and during Hugo’s childhood, years of political turmoil, his family moved frequently, including to Italy and Spain. He settled in Paris with his mother in 1812, where he developed his literary talents, publishing his first novel in 1825. Hugo’s numerous works of fiction and poetry increasingly took up social injustices, and, after being elected to the Academie Française over the objections of opponents of Romanticism, he became increasingly involved in national politics. His novel Notre-Dame de Paris (The Hunchback of Notre Dame, 1831) helped inspire the restoration of Paris’s cathedral, and a renewed appreciation of Paris’s pre-Renaissance physiognomy. It was published a year after the establishment of the Comité des Arts, later transformed into the Commission de Monuments Historiques with Ludovic Vitet (1802-73) as Inspector General. -

Subasta Octubre 2019

Subasta Octubre 2019 MITTWOCH 9 OKTOBER 2019 KL. 16:00 CEST (1 - 481) 1. LOMBARD SCHOOL. Gold reliquary medallion, late 16th 9. Jewellery set consisting of a brooch and earrings in gold, first Century - early 17th Century. half of the 19th Century. 18K gold, black enamel and central medallion depicting the Adoration of 14K gold, gilt metal and oval, round and square cut garnets, 1.80 cts the Shepherds on the front and the Flight to Egypt on the back, in approx. Brooch: 5.4x4.5 cm. Earrings: 4.3 cm. 20.5 gr. reverse-glass painting and églomisé. 4.8 x 3.8 cm. 31.8 gr. Schätzwert: 750 EUR Schätzwert: 550 EUR Endpreis: - Endpreis: 1.800 EUR 10. Catalan silver long earrings, 19th Century. 2. Two reliquary pendants, 17th-18th centuries. Silver, probably oval, cushion and pear cut topazes, 2.85 cts and rose One of them in the shape of Jerusalem Cross in silver and wood with cut diamonds, 0.25 cts approx. Original case included. 5.8 x 1.4 cm. mother of pearl inlays; and the other one as a medallion depicting Our 13.9 gr. Lady of Sorrows with the attributes of passion on the front and Saint Schätzwert: 300 EUR Margaret in an illuminated engraving on the back. 7.5x4.8 cm and 7x4.7 Endpreis: 650 EUR cm. 56.3 gr. Schätzwert: 550 EUR 11. Coral long earrings and bracelet, 19th Century. Endpreis: - 14K and 18K gold, coral beads, two flower-shaped coral beads, carved coral beads and coral cameo with the representation of a male bust. -

La Défense / Zone B (1953-91): Light and Shadows of the French Welfare State Pierre Chabard

71 La Défense / Zone B (1953-91): Light and Shadows of the French Welfare State Pierre Chabard The business district of La Défense, with its luxu- The history of La Défense Zone B during the rious office buildings, is a typical example of the second half of the twentieth century gives a very French version of welfare state policy1: centralism, clear - and even caricatural - illustration not only of modernism, and confusion between public and the urban and architectural consequences of the private elites.2 This district was initially planned in French welfare state - both positive and negative 1958 by the Etablissement Public d’Aménagement - but also of its crisis, which emerged in the 1970s de la région de La Défense (EPAD), the first such and influenced the development of other types of planning organism controlled by the state. But this urban governance and planning. Therefore, Zone B district, called Zone A (130 ha), constitutes only a offers a relevant terrain for analysing relationships small part of the operational sector of the EPAD; between the political and architectural aspects of the other part, Zone B (620 ha), coincides with the this history since the end of World War II. Indeed, northern part of the city of Nanterre, capital of the this case study suggests a rather unexpected double Hauts-de-Seine district. Characterized for a long assumption: while French architecture of the 1950s time by agriculture and market gardening, this city and 1960s is generally considered by architectural underwent a strong process of industrialization history as pompous, authoritarian and subjected to at the turn of the twentieth century, welcoming a power, here it can appear incredibly free, inventive great number of workers and immigrants, a popula- and experimental. -

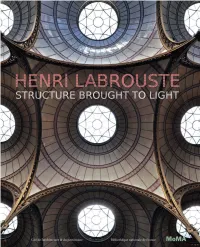

Henri Labrouste: Structure Brought to Light Is the Condensed Result of Several Years of Research, Goers Are Plunged

HENRI LABROUSTE STRUCTURE BROUGHT TO LIGHT With essays by Martin Bressani, Marc Grignon, Marie-Hélène de La Mure, Neil Levine, Bertrand Lemoine, Sigrid de Jong, David Van Zanten, and Gérard Uniack The Museum of Modern Art, New York In association with the Cité de l’architecture & du patrimoine et the Bibliothèque nationale de France, with the special participation of the Académie d’architecture and the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève. This exhibition, the first the Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine has devoted to Since its foundation eighty years ago, MoMA’s Department of Architecture (today the a nineteenth-century architect, is part of a larger series of monographs dedicated Department of Architecture and Design) has shared the Museum’s linked missions of to renowned architects, from Jacques Androuet du Cerceau to Claude Parent and showcasing cutting-edge artistic work in all media and exploring the longer prehistory of Christian de Portzamparc. the artistic present. In 1932, for instance, no sooner had Philip Johnson, Henry-Russell Presenting Henri Labrouste at the Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine carries with Hitchcock, and Alfred H. Barr, Jr., installed the Department’s legendary inaugural show, it its very own significance, given that his name and ideas crossed paths with our insti- Modern Architecture: International Exhibition, than plans were afoot for a show the following tution’s history, and his works are a testament to the values he defended. In 1858, he year on the commercial architecture of late-nineteenth-century Chicago, intended as the even sketched out a plan for reconstructing the Ecole Polytechnique on Chaillot hill, first in a series of shows tracing key episodes in the development of modern architecture though it would never be followed through. -

Baroque Architecture

'"" ^ 'J^. rfCur'. Fig. I. — Venice. S. Maria della Salute. (See pp. 88-90.) BAROQUE ARCHITECTURE BY MARTIN SHAW BRIGGS A.K.I. B. A. " iAulhor of " In the Heel of Italy WITH 109 ILLUSTRATIONS NEW YORK ; ' McBRIDE, NAST & COMPANY ^ y 1914 ,iMvMV NA (^Ay n^/i/j reserved) In all ages there have been some excellent workmen, and some excellent work done.—Walter Pater. PREFACE is commonly supposed that the purpose of a preface is to IT explain the scope of a book to those who do not read so far as the first page. There is a touch of cynicism in such an opinion which makes one loth to accept it, but I prefer to meet my troubles half way by stating at the outset what I have emphasized in my last chapter—that this book is not in any way an attempt to create a wholesale revival of Baroque Architecture in England. It is simply a history of a complex and neglected period, and has been prepared in the uncertain intervals of an architectural practice. The difficulty of the work has been increased by the fact that the subject has never been dealt with as a whole in any language previously. Gurlitt in his Geschichte des Barockstiles, published in 1887, covered a considerable part of the ground, but his work is very scarce and expensive. To students his volumes may be recommended for their numerous plans, but for details and general views they are less valuable. In recent years several fine mono- graphs have appeared dealing with Baroque buildings in specific districts, and very recently in a new international series the principal buildings of the period in Germany and Italy have been illustrated. -

National Architectures in Europe

The Monument National Architectures in Europe Fabienne CHEVALLIER ABSTRACT The concept of a national architecture was born in the eighteenth century in England, where the Neo-Gothic emerged as a symbol of the kingdom’s influence and would soon been reoriented by the Arts and Crafts movement towards the vernacular. In Germany, the completion of Cologne Cathedral gave the movement an ultra-romantic appearance, which competed with the Rundbogenstil. In France, the Neo-Gothic, which was theorized by rationalist architects close to Viollet-le-Duc, competed with the more regionalist Neo-Romanesque movement. National architectures then proliferated in Europe from 1880 to 1920. The primary ingredients of this architectural recycling of the past included popular culture (Hungary), the mythical roots of territories (Finland, Catalonia), and the natural beauty of local materials (Sweden). Stockholm's city hall, facade on the lake Mälar. Arch. Ragnar ÖSTBERG (1911-1923). J. ROOSVAL dir., Stockholms Stadshus, Stockholm, Gunnar Tisells tekniska förlag, 1923. Paris, Bib. Nordique. The movement of national architectures, whose matrix was the Neo-Gothic, was born during the eighteenth century in England, and spread to Germany, France, and later to numerous centres in Europe. It ended during the 1920s. The picturesque English world—the melancholy of ruins, the sublime, Christian piety, idealization of the Middle Ages—prepared the way for romanticism, which was consubstantial with national architectures. From the early eighteenth century, the Gothic—which was used during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603) in an approach explicitly linked to strengthening the kingdom and English identity—became the style of the picturesque movement. -

Caractère Types and the Beaux - Arts Tradition: Interpreting Academic Typologies of Form and Decorum

Athens Journal of Architecture - Volume 3, Issue 3 – Pages 227-250 Caractère Types and the Beaux - Arts Tradition: Interpreting Academic Typologies of Form and Decorum By Diane Viegut Al Shihabi The articulation of caractère types, or variations and qualities of architectural caractère, in Beaux-Arts interiors and how they transposed when translated in another culture are infrequently explored in design historical scholarship. Discerning the theories and doctrines of caractère types in French academic architecture will help illuminate the Académie’s paramount objectives and also distinguish its intended meanings across cultures. This study asked (1) what historical and theoretical principles underlay the primary expressions of architectural caractère in the French Beaux-Arts tradition, and (2) how did caractère expressions manifest in Beaux-Arts interiors in France and abroad? It argues that the French Académie developed caractère types to communicate specific information about artistic history and contemporary society, in terms of tradition, purpose, and ingenuity. The paper’s research methodology integrated literary analysis of period works, content analysis of architects’ documents, material culture analysis of interiors, and iconographical analysis of symbolism. The study finds that preeminent caractère types in Beaux-Arts interiors, consistently reflected each room’s purpose and its social importance through a classical and art historical form language that visually persisted when interpreted beyond France. Further, the connotations of visual social hierarchies varied over time and by location, and were individualized through discreet cultural semiotics, making the French architectural tradition germane to other sovereign states. The information is of value to academicians and practitioners, including historic preservationists and contemporary Neo Beaux-Arts classicists. -

Autographes & Manuscrits

_25_06_15 AUTOGRAPHES & MANUSCRITS & AUTOGRAPHES Pierre Bergé & associés Société de Ventes Volontaires_agrément n°2002-128 du 04.04.02 Paris 92 avenue d’Iéna 75116 Paris T. +33 (0)1 49 49 90 00 F. +33 (0)1 49 49 90 01 Bruxelles Avenue du Général de Gaulle 47 - 1050 Bruxelles Autographes & Manuscrits T. +32 (0)2 504 80 30 F. +32 (0)2 513 21 65 PARIS - JEUDI 25 juIN 2015 www.pba-auctions.com VENTE AUX ENCHÈRES PUBLIQUES PARIS Pierre Bergé & associés AUTOGRAPHES & MANUSCRITS DATE DE LA VENTE / DATE OF THE AUCTION Jeudi 25 juin 2015 - 13 heures 30 June Thursday 25th 2015 at 1:30 pm LIEU DE VENTE / LOCATION Drouot-Richelieu - Salle 8 9, rue Drouot 75009 Paris EXPOSITION PRIVÉE / PRIVATE VieWinG Sur rendez-vous à la Librairie Les Autographes 45 rue de l’Abbé Grégoire 75006 Paris T. + 33 (0)1 45 48 25 31 EXPOSITIONS PUBLIQUES / PUBlic VieWinG Mercredi 24 juin de 11 heures à 18 heures Jeudi 25 juin de 11 heures à 12 heures June Wednesday 24th from 11:00 am to 6:00 pm June Thursday 25th from 11:00 am to 12:00 pm TÉLÉPHONE PENDANT L’EXPOSITION PUBLIQUE ET LA VENTE T. +33 (0)1 48 00 20 08 CONTACTS POUR LA VENTE Eric Masquelier T. + 33 (0)1 49 49 90 31 - [email protected] Sophie Duvillier T. + 33 (0)1 49 49 90 10 - [email protected] EXPERT POUR LA VENTE Thierry Bodin Syndicat Français des Experts Professionnels en Œuvres d'Art 45 rue de l'Abbé Grégoire, 75006 Paris T. -

Architectural Interiors I Prepared Especially for Home Study

r 720 (07) 157 v. 6 Federal Housing Acbnmistration Library)^ ^ J. pC~. -=rv J J. m J J n%A MMfaHNK,** ■ ' • ^•SiSfcK.iS iiii&j*t&Mis 53«*« International Correspondence Schools, Scranton, Pa. ! | Architectural Interiors I Prepared Especially for Home Study By DAVID T. JONES, B. Arch. Director, School of Architecture and Building Construction International Correspondence Schools Member, American Institute of Architects 641 l-l Edition 2 International Correspondence Schools, Scranton, Pennsylvania International Correspondence Schools, Canadian, Ltd., Montreal, Canada i j 1 ;i ! i Architectural Interiors ■ vY- ! '‘I And m Lite ihai most atlairs thu» require suriou* handling arc distasteful, For this reason, 1 have By always believed that the successiul man has the hardest battle with nimtelf rather than with the other fellow DAVID T. JONES, B. Arch. To bring ones ielf to a frame of mind and to the proper energy to accomplish tnings that require plain Director, School of Architecture hard work continuously is the one big battle tbtu and Building Construction I everyone has. When this battle is woo for all time, International Correspondence Schools then everything is eas).” —Thomas A Buckner Member, American Institute of Architects l i- f 33 Serial 6411-1 ! I : i ;■! © 1962, 1958 by INTERNATIONAL TEXTBOOK COMPANY Printed in United States of America :1 :i •! : !r International Correspondence Schools j Scranton, Pennsylvania / ICS International Correspondence Schools Canadian, Ltd, Montreal, Canada L 710^ (p i? inv-£ fFTiat T/iis Text Covers • . 1. Development of Interior Design Pages 1 to 6 The relation between architecture and interior design and decora- ration is explained. -

Architecture and Engineering Theme: Period Revival, 1919-1950 Theme: Housing the Masses, 1880-1980 Sub-Theme: Period Revival Neighborhoods, 1918-1942

LOS ANGELES CITYWIDE HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT Context: Architecture and Engineering Theme: Period Revival, 1919-1950 Theme: Housing the Masses, 1880-1980 Sub-Theme: Period Revival Neighborhoods, 1918-1942 Prepared for: City of Los Angeles Department of City Planning Office of Historic Resources JANUARY 2016 SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement Architecture and Engineering/Period Revival; Housing the Masses/Period Revival Neighborhoods TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 3 CONTRIBUTORS 3 INTRODUCTION 3 HISTORICAL CONTEXT 5 THEME: PERIOD REVIVAL, 1919-1950 11 SUB-THEME: French Norman, 1919-1940 11 SUB-THEME: Storybook, 1919-1950 15 SUB-THEME: Late Tudor Revival, 1930-1950 20 SUB-THEME: Late Gothic Revival, 1919-1939 24 SUB-THEME: Chateauesque, 1919-1950 29 THEME: HOUSING THE MASSES, 1880-1980 33 SUB-THEME: Period Revival Neighborhoods, 1918-1942 33 SUB-THEME: Period Revival Multi-Family Residential Neighborhoods, 1918-1942 39 SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY 44 Page | 2 SurveyLA Citywide Historic Context Statement Architecture and Engineering/Period Revival; Housing the Masses/Period Revival Neighborhoods PREFACE These themes are components of Los Angeles’ citywide historic context statement and provide guidance to field surveyors in identifying and evaluating potential historic resources relating to Period Revival architecture. Refer to www.HistoricPlacesLA.org for information on designated resources associated with these themes as well as those identified through SurveyLA and other surveys. CONTRIBUTORS Teresa Grimes and Allison Lyons, GPA Consulting. Ms. Grimes is a Principal Architectural Historian at GPA Consulting. She earned her Master of Arts degree in Architecture from the University of California, Los Angeles and has over twenty-five years of experience in the field. Ms.