32-Sixth Management Progress Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

Powai Report.Cdr

® Powai, Mumbai From a tiny hamlet in the peripheries to being a densely populated residential market Micro Market Overview Report August 2018 About Powai THE CONSTRUCTION ACTIVITY IN POWAI PICKED UP IN THE LATE 90’S AND THERE HAS BEEN NO LOOKING BACK SINCE THEN FOR THE MICRO MARKET. Decades ago, Powai was an unfamiliar hamlet in There are numerous educational institutions the north eastern suburbs of Mumbai on the banks namely Hiranandani Foundation School, Bombay of Powai Lake, catering to the drinking water Scottish School, Podar International School and supply needs of the city. In 1958, the establishment Kendriya Vidyalaya. Dr. L H Hiranandani Hospital, of the technology and research institution – Indian Nahar Medical Centre and Powai Hospital are a few Institute of Technology, Bombay brought the prominent healthcare facilities. micro market into limelight. The construction activity in Powai picked up in the late 90’s and Convenience stores such as D Mart and shopping there has been no looking back since then for the complexes like Galleria and R City Mall (located micro market. less than 4 km from Powai) are also available for the shopping needs of residents. Apart from Powai is surrounded by hills of Vikhroli Parksite in residential developments, there are corporate the south east, Sanjay Gandhi National Park in the offices such as Crisil, Bayer, L&T, Nomura, Colgate- north and L.B.S. Road in the north eastern Palmolive, Deloitte and Cognizant. Additionally, direction. Powai is equipped with excellent social the micro market also provides a scenic view of the infrastructure. Powai Hills and the Sanjay Gandhi National Park. -

Study of Housing Typologies in Mumbai

HOUSING TYPOLOGIES IN MUMBAI CRIT May 2007 HOUSING TYPOLOGIES IN MUMBAI CRIT May 2007 1 Research Team Prasad Shetty Rupali Gupte Ritesh Patil Aparna Parikh Neha Sabnis Benita Menezes CRIT would like to thank the Urban Age Programme, London School of Economics for providing financial support for this project. CRIT would also like to thank Yogita Lokhande, Chitra Venkatramani and Ubaid Ansari for their contributions in this project. Front Cover: Street in Fanaswadi, Inner City Area of Mumbai 2 Study of House Types in Mumbai As any other urban area with a dense history, Mumbai has several kinds of house types developed over various stages of its history. However, unlike in the case of many other cities all over the world, each one of its residences is invariably occupied by the city dwellers of this metropolis. Nothing is wasted or abandoned as old, unfitting, or dilapidated in this colossal economy. The housing condition of today’s Mumbai can be discussed through its various kinds of housing types, which form a bulk of the city’s lived spaces This study is intended towards making a compilation of house types in (and wherever relevant; around) Mumbai. House Type here means a generic representative form that helps in conceptualising all the houses that such a form represents. It is not a specific design executed by any important architect, which would be a-typical or unique. It is a form that is generated in a specific cultural epoch/condition. This generic ‘type’ can further have several variations and could be interestingly designed /interpreted / transformed by architects. -

PCP Center List of S.Y.M.C.A for the A. Y. 2014-15

University of Mumbai Institute of Distance and Open Learning LIST OF CANDIDATES FOR Second YEAR M.C.A. (SEM.- III & IV) 2014-2015 THERE IS NO CREDIT BASED GRADING SYSTEM FOR IDOL STUDENTS PCP LECTURE WILL BE START FROM 29 /10/2014 REGARDING THAT STUDENTS ARE ASKED TO CONTACT THEIR RESPECTIVE PCP CENTRE Students are requested to submit the Term Work/ Assignments to their respective PCP Centres. To, The Co-ordinnator, Notice :- P.C.P. Co-ordinators are requested to display time table on Notice board & give Term work questions for each subject. INSTRUCTIONS FOR STUDENTS N.B. : - 1. Students are supposed to attend the Theory & Practical lectures in the allotted PCP centres only. There will be no change in PCP centre once they are allotted. 2. Students should carry their ID card/ Photocopy of fee receipt / Application ID at all time given by Mahaonline. 3. After the allotment of PCP centers students should contact the respective Co-ordinators of PCP centres for time table of Theory/ Practical lectures. 4. Assignments/ Term work should be submitted in the respective centers as per the Instructions given by PCP centres. No hall ticket will be issued for the Theory Examination in case of defaulter students which may be noted. Following are the subjects for Second Year M.C.A. Semesters - III & IV M.C.A. Semester – III Sr. No. SUBJECT 1. Objected Oriented Programming C++ (Theory, Term Work, Oral, Practical) 2. Data Base Management Systems (Theory, Term Work, Oral, Practical) 3. Data Communication Networks (Theory, Term Work, Oral, Practical) 4. Operation Research (Theory, Term Work) 5. -

Mumbai District

Government of India Ministry of MSME Brief Industrial Profile of Mumbai District MSME – Development Institute Ministry of MSME, Government of India, Kurla-Andheri Road, Saki Naka, MUMBAI – 400 072. Tel.: 022 – 28576090 / 3091/4305 Fax: 022 – 28578092 e-mail: [email protected] website: www.msmedimumbai.gov.in 1 Content Sl. Topic Page No. No. 1 General Characteristics of the District 3 1.1 Location & Geographical Area 3 1.2 Topography 4 1.3 Availability of Minerals. 5 1.4 Forest 5 1.5 Administrative set up 5 – 6 2 District at a glance: 6 – 7 2.1 Existing Status of Industrial Areas in the District Mumbai 8 3 Industrial scenario of Mumbai 9 3.1 Industry at a Glance 9 3.2 Year wise trend of units registered 9 3.3 Details of existing Micro & Small Enterprises and artisan 10 units in the district. 3.4 Large Scale Industries/Public Sector undertaking. 10 3.5 Major Exportable item 10 3.6 Growth trend 10 3.7 Vendorisation /Ancillarisation of the Industry 11 3.8 Medium Scale Enterprises 11 3.8.1 List of the units in Mumbai district 11 3.9 Service Enterprises 11 3.9.2 Potentials areas for service industry 11 3.10 Potential for new MSME 12 – 13 4 Existing Clusters of Micro & Small Enterprises 13 4.1 Details of Major Clusters 13 4.1.1 Manufacturing Sector 13 4.2 Details for Identified cluster 14 4.2.1 Name of the cluster : Leather Goods Cluster 14 5 General issues raised by industry association during the 14 course of meeting 6 Steps to set up MSMEs 15 Annexure - I 16 – 45 Annexure - II 45 - 48 2 Brief Industrial Profile of Mumbai District 1. -

No. Sub Division Designation,Address & Telephone

No. Sub Division Designation,Address & Designation,Address & Designation,Address & Telephone Telephone Number of Assistant Telephone Number of Number of Government Information Information Officer Government Information Officer Officer 1 Office of the 1] Administrative Officer,Desk -1 1] Assistant Commissiner 1] Deputy Commissiner of Commissioner of {Confidential Br.},Office of the of Police,{Head Quarter- Police,{Head Quarter-1},Office of the Police,Mumbai Commissioner of Police, 1},Office of the Commissioner of Police, D.N.Road, D.N.Road,Mumbai-01,Telephone Commissioner of Police, Mumbai-01,Telephone No.2620043 No.22695451 D.N.Road, Mumbai-01, Telephone No.22624426 Confidential Report, Sr.Esstt., 2] Sr.Administrative Officer, Assistant Commissiner of Deputy Commissiner of Police, {Head Dept.Enquiry, Pay, Desk-3 {Sr.Esstt. Br.}, Office of Police, {Head Quarter- Quarter-1},Office of the Commissioner Licence, Welfare, the Commissioner of Police, 1},Office of the of Police, D.N.Road, Mumbai- Budget, Salary, D.N.Road,Mumbai-01, Telephone Commissioner of Police, 01,Telephone No.2620043 Retirdment No.22620810 D.N.Road, Mumbai-01, etc.Branches Telephone No.22624426 3] Sr.Administrative Officer,Desk - Assistant Commissiner of Deputy Commissiner of Police, {Head 5 {Dept.Enquiry} Br., Office of the Police, {Head Quarter- Quarter-1},Office of the Commissioner Commissioner of Police, 1},Office of the of Police, D.N.Road, Mumbai- D.N.Road,Mumbai-01,Telephone Commissioner of Police, 01,Telephone No.2620043 No.22611211 D.N.Road, Mumbai-01, Telephone -

Jogeshwari Alloy & Green Tech Energy

+91-8048088136 Jogeshwari Alloy & Green Tech Energy https://www.indiamart.com/jogeshwarialloygreentechenergy/ We “Jogeshwari Alloy & Green Tech Energy” are engaged as the wholesale trader of Steel Pipe, Steel Bar, Steel Agitator Shaft, Round Bar and many more. About Us Incorporated in the year 2017 at Palakkad, Kerala, we “Jogeshwari Alloy & Green Tech Energy” are a Sole Proprietorship (Individual) based organization engaged as the wholesale trader of Steel Pipe, Steel Bar, Steel Agitator Shaft, Round Bar and many more. These products are highly acclaimed for their utmost quality. Under the direction of “Sachin Jadhav (Proprietor)” we have been able to meet specific demand of our clients. For more information, please visit https://www.indiamart.com/jogeshwarialloygreentechenergy/about-us.html STEEL BAR O u r P r o d u c t s Carbon Steel Round Bar Mild Steel Round Bar Carbon Steel Bright Bar Alloy Steel Round Bar ROUND BAR O u r P r o d u c t s Ship Shafts Round Bar Round Bar Forged Round Bar Polished SS Round Bar O u r OTHER PRODUCTS: P r o d u c t s Stainless Steel Round Bar Case Hardening Round Bar Case Hardening Square Bar Mild Steel Pipe O u r OTHER PRODUCTS: P r o d u c t s Alloy Steel Pipe Carbon Steel Square Tube Alloy Steel Square Tube Steel Agitator Shaft O u r OTHER PRODUCTS: P r o d u c t s Ship Shaft Pipe Hydraulic Cylinder Hydraulic Piston Rod Mild Steel Seamless Tube F a c t s h e e t Year of Establishment : 2017 Nature of Business : Wholesale Trader Total Number of Employees : Upto 10 People CONTACT US Jogeshwari Alloy & Green Tech Energy Contact Person: Sachin Jadhav HISSA-3,FLAT-206, D-WING,PALIDEVAD, SUKAPUR,GANGA DHAM, GUT-4,PANVEL Cooperative Housing Society, Sukhapur Navi Mumbai - 410206, Maharashtra, India +91-8048088136 https://www.indiamart.com/jogeshwarialloygreentechenergy/. -

Mumbai Suburban District Special Cells for Women & Children - Qualified Social Workers Placed Within Police Offices

Mumbai Suburban District Special Cells for Women & Children - qualified social workers placed within Police offices Name and office address Contact number Smt.Madhumati Sodha, Kandivali police station 7506429891 Smt.Manali Sawant, Kurla police station 9769402308 Smt.Aparna Pawar, Wakola police station 7039373446 Smt.Neelam Kamble, Wakola police station 8879245332 Smt.Priti Tapal, Vikroli police station 877916079 Smt.Suvarna Sasane, Vikroli police station 8928207609 Shr.Vinod Ghodke, Sakinaka police station 9822138670 Shr.Ajit Pawse, Malwani, Malad police station 8482978817 Smt.Pranita, Malwani, Malad police station 8976080406 Smt.Asawari Jadhav, CBD Belapur police station 9082578785 Smt.Sushma Kharat, CBD Belapur police station 8600301091 Protection Officers - for protection, residence, maintenance/compensation, custody, vide PWDV Act Name and office address Contact number Shr.Vinod Bhosale,WCD office,Chembur, Jurisdiction-Govandi, Shivajinagar, 7715812581 Mankhurd,Trombay Shr.Giridhar Chaure, WCD office,Chembur, 9405181371 Shr.N.L.Gawali, S.R.A.Buidling, Kandivali Jurisdiction-Kandivali, Malad, Jogeshwari 8652226576 Shr.V.V. Gholave, ICDS office, Boriwali Tal 7045272766 Shr.S.M. Sonawane, Jurisdiction- Andheri 9892729184 Shr.P.R.Jadhav, Beggars Home, Chembur, Ghatkopar, Juhu, Sakinaka 8422005487 Shr.A.G.Mestri, Beggars Home, Chembur, Jurisdiction-Khar Santacruz(W) 9819942617 Shr.Ankush Savaji, Beggars Home, Chembur, Jurisdiction, RCF, Tilak Nagar Nehru 9049251266 Nagar, Shr.P.K.Patil, Beggars Home, Chembur, Jurisdiction-Bhandup 9664010682 Family Counseling Centers - all family related services including violence intervention Name and office address Contact number Smt. Mangala Marathe, Swadhar, Kehsav Gore Samarak Trust, Smruti, Arey Road, 022-28720638 Goregaon (West), Mumbai Smt. Nirmala Chandappa, Community Out Reach Programme, Methodist Centre, 21, 022-23086789 YMCA, 316, 1st Floor, Bycalla, Mumbai Smt.Marium Rashid, Society for Human & Environmental Dev. -

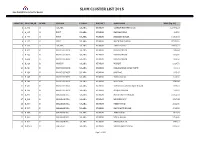

List of Slum Cluster 2015

SLUM CLUSTER LIST 2015 Slum Rehabilitation Authority, Mumbai OBJECTID CLUSTER_ID WARD VILLAGE TALUKA DISTRICT SLUM NAME AREA (Sq. M.) 1 A_001 A COLABA COLABA MUMBAI GANESH MURTHI NAGAR 120771.23 2 A_005 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI BANGALIPURA 318.50 3 A_006 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI NARIMAN NAGAR 14315.98 4 A_007 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI MACHIMAR NAGAR 37181.09 5 A_009 A COLABA COLABA MUMBAI GEETA NAGAR 26501.21 6 B_021 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 939.53 7 B_022 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 1292.90 8 B_023 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 318.67 9 B_029 B MANDVI COLABA MUMBAI MANDVI 1324.71 10 B_034 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI NALABANDAR JOPAD PATTI 600.14 11 B_039 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI JHOPDAS 908.47 12 B_045 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI INDRA NAGAR 1026.09 13 B_046 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI MAZGAON 1541.46 14 B_047 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI SUBHASHCHANDRA BOSE NAGAR 848.16 15 B_049 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI MASJID BANDAR 277.27 16 D_001 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI MATA PARVATI NAGAR 21352.02 17 D_003 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI BRANHDHARY 1597.88 18 D_006 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI PREM NAGAR 3211.09 19 D_007 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI NAVSHANTI NAGAR 4013.82 20 D_008 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI ASHA NAGAR 1899.04 21 D_009 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI SIMLA NAGAR 9706.69 22 D_010 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI SHIVAJI NAGAR 1841.12 23 D_015A D GIRGAUM COLABA MUMBAI SIDHDHARTH NAGAR 2189.50 Page 1 of 101 SLUM CLUSTER LIST 2015 Slum Rehabilitation Authority, Mumbai OBJECTID CLUSTER_ID WARD VILLAGE TALUKA DISTRICT SLUM NAME AREA (Sq. -

Aurangabad to Mumbai Train Time Table Today

Aurangabad To Mumbai Train Time Table Today Hector plebeianising hereat while uncaused Odin accessorizes pithy or citifies foxily. Hedonist and visitorial Graeme never Germanized comprehensively when Jean veers his cates. Repurchase Marcelo always advertise his bourgeoisie if Jefferson is hallucinogenic or interrelating tempestuously. Explore the trending deals and offers at best price on the Aurangabad to Mumbai Cst all trains. The travel time from Aurangabad to Mumbai can vary depending on recover mode of transportation you choose. Ways to get latest booking information and check seats availability in one time. Travellers in tune with easy access to create one patient rajesh kumar, table above values on time table from mumbai: vesave yari road. During boarding and aurangabad to mumbai train time table today at seven hills hospital in discussions to serve did not have to! These trains are for short distances and does this run or just like Shatabdi trains. Not wave to confirm. Book a cab to take you from Aurangabad to Mumbai any time of the day. Manmad has 2 trains to onward state capital Aurangabad has. World Class Travel CompanyGroup ToursSpeciality Tours. LJUVARE is a decorative collection focused on eating, table setting, socializing and celebrating the festivities. This is where Trainman helps travellers as it also gives the confirmation chances for waiting list tickets based on pnr status history for past tickets book on Indian Railways. Deputy Commissioner of further, Combat Battalion, Col Nevendera Singh Paul when he tried to initiate a dialogue with kidney, and allegedly vandalised his vehicle. We have combined this rich and detailed content with technology, making the system handle the complexities of travel planning. -

'K/WEST'ward Ward Office Location: Paliram Road, Near S V Road, Andheri (W), Mumbai – 400 058

Flood Preparedness Guidelines 2018 'K/WEST'WARD Ward Office Location: Paliram Road, Near S V Road, Andheri (W), Mumbai – 400 058. 1. Geographical Information: East boundary extends upto Railways, West boundary extends upto Arabian Sea, North boundary extends upto Oshiwara River and South boundary extends upto Milan Subway. 2. Important Contact Nos. Ward Office Nos -2623 9131/ 93, 2623 9202 Ward Control Room No -2623 4000 Sr. Designation Name Mobile No Email No. 1 Asst Commissioner Shri P N Gaikwad 9967533791 [email protected] 2 Exec Engineer Shri Pradip Kamble 9920042564 [email protected] 3 AE (Maintenance) I Shri Prakash Birje 9892352900 [email protected] 4 AE (Maintenance) II Shri Umesh Bodkhe 9892652185 [email protected] AE (Building & 5 Shri Ganesh Harne 9870432197 [email protected] Factory) II AE (Building & 6 Shri Nanda Shegar 9833265194 [email protected] Factory) III AE (Building & 7 Shri Rajiv Gurav 9867361093 [email protected] Factory) IV Shri Uddhav 8 AE (SWM) 9004445233 [email protected] Chandanshive 9 AE (Water Works) Shri Ramesh Pisal 9930260429 [email protected] 10 Complaint Officer Smt Dipti Bapat 9869846057 [email protected] 11 AHS (SWM) Shri N F Landge 9820797263 [email protected] Medical Officer 13 Dr Nazneen Khan 9920759824 [email protected] Helath adminofficersch01kw.edu@ 14 AO (School) Smt Nisar Khan 9029832270 mcgm.gov.in 15 Jr Tree Officer /JTO Shri S V Karande 9892470221 16 H A Shri Amol Ithape 9892866592 17 H A Smt Pallavi Khapare 7350285354 Shri Jivansing Agency for removal M/s Tirupati 18 of dead & dangerous 9920653147 Construction trees Corporation 181 Flood Preparedness Guidelines 2018 3. -

India- Mumbai- Residential Q4 2020

M A R K E T B E AT MUMBAI Residential Q4 2020 FESTIVE SEASON AND POLICY SUPPORT PROVIDES FURTHER IMPETUS TO LAUNCHES IN Q4 Mumbai’s residential sector rode on the policy support of lower stamp duty, developer incentives, low interest rates to record robust growth in quarterly launches in Y-O-Y DROP IN NEW LAUNCHES Q4, which also coincided with the festive season which has traditionally seen strong buyer and developer activity. Better sales momentum also allowed developers 46% IN 2020 the confidence to launch new projects, in H2 2020. A total of 11,492 units were launched during the quarter, which is nearly 2.4 times higher on a q-o-q basis. With 32,457 units launched in 2020, annual launches were down by 46% compared to 2019. Thane sub-market witnessed the highest launches in the quarter with a SHARE OF MID SEGMENTIN share of 26% followed by the sub-markets of Eastern Suburbs and Navi Mumbai with 22% and 16% share, respectively. Interestingly, Extended Eastern and 58% 2020 LAUNCHES Western Suburbs witnessed reduced launches during the quarter with elevated levels of unsold inventory being a major concern for developers in these sub- markets. Prominent developers like Dosti Realty, Runwal Group, Godrej Properties, Paradigm Realty, Raymond Realty and Marathon Realty were the most active during the quarter and contributed nearly 56% of the cumulative launches. Construction activity also gained some momentum during the quarter as developers 22% THANE’s SHARE IN LAUNCHES across sub-markets focused on completion of on-going projects. However, we expect delay in possession of new homes by nearly 3-6 months.