Native Peoples' Relationship to the California Chaparral

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summary of Offerings in the PBS Bulb Exchange, Dec 2012- Nov 2019

Summary of offerings in the PBS Bulb Exchange, Dec 2012- Nov 2019 3841 Number of items in BX 301 thru BX 463 1815 Number of unique text strings used as taxa 990 Taxa offered as bulbs 1056 Taxa offered as seeds 308 Number of genera This does not include the SXs. Top 20 Most Oft Listed: BULBS Times listed SEEDS Times listed Oxalis obtusa 53 Zephyranthes primulina 20 Oxalis flava 36 Rhodophiala bifida 14 Oxalis hirta 25 Habranthus tubispathus 13 Oxalis bowiei 22 Moraea villosa 13 Ferraria crispa 20 Veltheimia bracteata 13 Oxalis sp. 20 Clivia miniata 12 Oxalis purpurea 18 Zephyranthes drummondii 12 Lachenalia mutabilis 17 Zephyranthes reginae 11 Moraea sp. 17 Amaryllis belladonna 10 Amaryllis belladonna 14 Calochortus venustus 10 Oxalis luteola 14 Zephyranthes fosteri 10 Albuca sp. 13 Calochortus luteus 9 Moraea villosa 13 Crinum bulbispermum 9 Oxalis caprina 13 Habranthus robustus 9 Oxalis imbricata 12 Haemanthus albiflos 9 Oxalis namaquana 12 Nerine bowdenii 9 Oxalis engleriana 11 Cyclamen graecum 8 Oxalis melanosticta 'Ken Aslet'11 Fritillaria affinis 8 Moraea ciliata 10 Habranthus brachyandrus 8 Oxalis commutata 10 Zephyranthes 'Pink Beauty' 8 Summary of offerings in the PBS Bulb Exchange, Dec 2012- Nov 2019 Most taxa specify to species level. 34 taxa were listed as Genus sp. for bulbs 23 taxa were listed as Genus sp. for seeds 141 taxa were listed with quoted 'Variety' Top 20 Most often listed Genera BULBS SEEDS Genus N items BXs Genus N items BXs Oxalis 450 64 Zephyranthes 202 35 Lachenalia 125 47 Calochortus 94 15 Moraea 99 31 Moraea -

Biological Resources Assessment

APPENDIX B: BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES ASSESSMENT BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES ASSESSMENT Sierra West Assisted Living and Memory Care Project City of Santa Clarita APNs 2827-005-042 & -043 Prepared for: MR. NORRIS WHITMORE P.O. Box 55786 Valencia, CA 91385 Attn: Mr. Norris Whitmore (661) 406-0961 Prepared by: ENVICOM CORPORATION 4165 E. Thousand Oaks Boulevard, Suite 290 WestlaKe Village, CA 91362 Contact: Jim Anderson, Senior Biologist (818) 879-4700 ext. 234 January 2020 Revised February 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 2.0 METHODS 1 2.1 Biological Resources Inventory 1 2.1.1 Literature Review 1 2.1.2 Field Survey 4 3.0 ENVIRONMENTAL SETTING 4 4.0 BIOLOGICAL RESOURCES 6 4.1 Vegetation and Plant Communities 6 4.1.1 Vegetation 6 4.1.2 Natural Communities of Special Concern 8 4.1.3 Plant Communities/Habitats Listed in CNDDB 9 4.2 Plant Species 10 4.2.1 Plant Species Observed 10 4.2.2 Special-Status Plant Species 10 4.3 Wildlife Species 12 4.3.1 Wildlife Observed 12 4.3.2 Special-Status Wildlife Species 12 4.4 Wildlife Movement 15 5.0 PROJECT IMPACTS 16 5.1 Impacts to Special-Status Plants 18 5.2 Impacts to Special-Status Wildlife 19 5.3 Impacts to Nesting Birds 20 6.0 REFERENCES 22 FIGURES Figure 1 Location Map 2 Figure 2 Aerial Image of the Project Site/Photo Location Map 3 Figure 3 Vegetation and Impacts Map 7 PLATE Plate 1 Representative Photographs of the Project Site and Habitats 5 Biological Resources Assessment S ierra West Assisted Living and Memory Care Project City of Santa Clarita i TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLES Table 1 Natural -

Survey for Special-Status Vascular Plant Species

SURVEY FOR SPECIAL-STATUS VASCULAR PLANT SPECIES For the proposed Eagle Canyon Fish Passage Project Tehama and Shasta Counties, California Prepared for: Tehama Environmental Solutions 910 Main Street, Suite D Red Bluff, California 96080 Prepared by: Dittes & Guardino Consulting P.O. Box 6 Los Molinos, California 96055 (530) 384-1774 [email protected] Eagle Canyon Fish Passage Improvement Project - Botany Report Sept. 12, 2018 Prepared by: Dittes & Guardino Consulting 1 SURVEY FOR SPECIAL-STATUS VASCULAR PLANT SPECIES Eagle Canyon Fish Passage Project Shasta & Tehama Counties, California T30N, R1W, SE 1/4 Sec. 25, SE1/4 Sec. 24, NE ¼ Sec. 36 of the Shingletown 7.5’ USGS Topographic Quadrangle TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................. 4 II. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 III. Project Description ............................................................................................................................................... 4 IV. Location .................................................................................................................................................................. 5 V. Methods .................................................................................................................................................................. -

P L a N T L I S T Water-Wise Trees and Shrubs for the High Plains

P L A N T L I S T Water-Wise Trees and Shrubs for the High Plains By Steve Scott, Cheyenne Botanic Gardens Horticulturist 03302004 © Cheyenne Botanic Gardens 2003 710 S. Lions Park Dr., Cheyenne WY, 82001 www.botanic.org The following is a list of suitable water-wise trees and shrubs that are suitable for water- wise landscaping also known as xeriscapes. Many of these plants may suffer if they are placed in areas receiving more than ¾ of an inch of water per week in summer. Even drought tolerant trees and shrubs are doomed to failure if grasses or weeds are growing directly under and around the plant, especially during the first few years. It is best to practice tillage, hoeing, hand pulling or an approved herbicide to kill all competing vegetation for the first five to eight years of establishment. Avoid sweetening the planting hole with manure or compost. If the soil is needs improvement, improve the whole area, not just the planting hole. Trees and shrubs generally do best well with no amendments. Many of the plants listed here are not available in department type stores. Your best bets for finding these plants will be in local nurseries- shop your hometown first! Take this list with you. Encourage nurseries and landscapers to carry these plants! For more information on any of these plants please contact the Cheyenne Botanic Gardens (307-637-6458), the Cheyenne Forestry Department (307-637-6428) or your favorite local nursery. CODE KEY- The code key below will assist you in selecting for appropriate characteristics. -

Amelanchierspp. Family: Rosaceae Serviceberry

Amelanchier spp. Family: Rosaceae Serviceberry The genus Amelanchier contains about 16 species native to North America [5], Mexico [2], and Eurasia to northern Africa [4]. The word amelanchier is derived from the French common name amelanche of the European serviceberry, Amelanchier ovalis. Amelanchier alnifolia-juneberry, Pacific serviceberry, pigeonberry, rocky mountain servicetree, sarvice, sarviceberry, saskatoon, saskatoon serviceberry, western service, western serviceberry , western shadbush Amelanchier arborea-Allegheny serviceberry, apple shadbush, downy serviceberry , northern smooth shadbush, shadblow, shadblown serviceberry, shadbush, shadbush serviceberry Amelanchier bartramiana-Bartram serviceberry Amelanchier canadensis-American lancewood, currant-tree, downy serviceberry, Indian cherry, Indian pear, Indian wild pear, juice plum, juneberry, may cherry, sugar plum, sarvice, servicetree, shadberry, shadblow, shadbush, shadbush serviceberry, shadflower, thicket serviceberry Amelanchier florida-Pacific serviceberry Amelanchier interior-inland serviceberry Amelanchier sanguinea-Huron serviceberry, roundleaf juneberry, roundleaf serviceberry , shore shadbush Amelanchier utahensis-Utah serviceberry Distribution In North America throughout upper elevations and temperate forests. The Tree Serviceberry is a shrub or tree that reaches a height of 40 ft (12 m) and a diameter of 2 ft (0.6 m). It grows in many soil types and occurs from swamps to mountainous hillsides. It flowers in early spring, producing delicate white flowers, making -

Jeremy Langley Chief Operations Officer Wilhite Langley, Inc. 21800 Barton Road, Ste 102 Grand Terrace, Ca 92313

47 1st Street, Suite 1 Redlands, CA 92373-4601 (909) 915-5900 May 22, 2019 Jeremy Langley Chief Operations Officer Wilhite Langley, Inc. 21800 Barton Road, Ste 102 Grand Terrace, Ca 92313 RE: Biological Resources Assessment, Jurisdictional Waters Delineation Glen Helen/Devore parcel - APN: 0261-161-17, Devore, CA Dear Mr. Langley: Jericho Systems, Inc. (Jericho) is pleased to provide this letter report that details the results of a general Biological Resources Assessment (BRA) that includes habitat suitability assessments for nesting birds, Burrowing owl (Athene cunicularia) [BUOW] and a Jurisdictional Waters Delineation (JD) for the proposed Glen Helen/Devore parcel (Project) located within Assessor’s Parcel Number (APN) #0261-161-17 in the community of Devore, CA (Attachment B: Figures 1 and 2). This report is designed to address potential effects of the proposed Project to designated Critical Habitats and/or any species currently listed or formally proposed for listing as endangered or threatened under the federal Endangered Species Act (ESA) and the California Endangered Species Act (CESA), or species designated as sensitive by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW), or the California Native Plant Society (CNPS). Attention was focused on sensitive species known to occur locally. This report also addresses resources protected under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, federal Clean Water Act (CWA) regulated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) and Regional Water Quality Control Board (RWQCB) respectively; and Section 1602 of the California Fish and Game Code (FCG) administered by the CDFW. SITE LOCATION The approximately 1-acre parcel (APN: 0261-161-17) is located north of Kendall Drive just north of the intersection with N. -

The Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Bird Conservation Plan

The Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Bird Conservation Plan A Strategy for Protecting and Managing Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Habitats and Associated Birds in California A Project of California Partners in Flight and PRBO Conservation Science The Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Bird Conservation Plan A Strategy for Protecting and Managing Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Habitats and Associated Birds in California Version 2.0 2004 Conservation Plan Authors Grant Ballard, PRBO Conservation Science Mary K. Chase, PRBO Conservation Science Tom Gardali, PRBO Conservation Science Geoffrey R. Geupel, PRBO Conservation Science Tonya Haff, PRBO Conservation Science (Currently at Museum of Natural History Collections, Environmental Studies Dept., University of CA) Aaron Holmes, PRBO Conservation Science Diana Humple, PRBO Conservation Science John C. Lovio, Naval Facilities Engineering Command, U.S. Navy (Currently at TAIC, San Diego) Mike Lynes, PRBO Conservation Science (Currently at Hastings University) Sandy Scoggin, PRBO Conservation Science (Currently at San Francisco Bay Joint Venture) Christopher Solek, Cal Poly Ponoma (Currently at UC Berkeley) Diana Stralberg, PRBO Conservation Science Species Account Authors Completed Accounts Mountain Quail - Kirsten Winter, Cleveland National Forest. Greater Roadrunner - Pete Famolaro, Sweetwater Authority Water District. Coastal Cactus Wren - Laszlo Szijj and Chris Solek, Cal Poly Pomona. Wrentit - Geoff Geupel, Grant Ballard, and Mary K. Chase, PRBO Conservation Science. Gray Vireo - Kirsten Winter, Cleveland National Forest. Black-chinned Sparrow - Kirsten Winter, Cleveland National Forest. Costa's Hummingbird (coastal) - Kirsten Winter, Cleveland National Forest. Sage Sparrow - Barbara A. Carlson, UC-Riverside Reserve System, and Mary K. Chase. California Gnatcatcher - Patrick Mock, URS Consultants (San Diego). Accounts in Progress Rufous-crowned Sparrow - Scott Morrison, The Nature Conservancy (San Diego). -

Indian Sandpaintings of Southern California

UC Merced Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology Title Indian Sandpaintings of Southern California Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/59b7c0n9 Journal Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, 9(1) ISSN 0191-3557 Author Cohen, Bill Publication Date 1987-07-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Journal of California and Great Basin Antliropology Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 4-34 (1987). Indian Sandpaintings of Southern California BILL COHEN, 746 Westholme Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90024. OANDPAINTINGS created by native south were similar in technique to the more elab ern Californians were sacred cosmological orate versions of the Navajo, they are less maps of the universe used primarily for the well known. This is because the Spanish moral instruction of young participants in a proscribed the religion in which they were psychedelic puberty ceremony. At other used and the modified native culture that times and places, the same constructions followed it was exterminated by the 1860s. could be the focus of other community ritu Southern California sandpaintings are among als, such as burials of cult participants, the rarest examples of aboriginal material ordeals associated with coming of age rites, culture because of the extreme secrecy in or vital elements in secret magical acts of which they were made, the fragility of the vengeance. The "paintings" are more accur materials employed, and the requirement that ately described as circular drawings made on the work be destroyed at the conclusion of the ground with colored earth and seeds, at the ceremony for which it was reproduced. -

Antileishmanial Compounds from Nature - Elucidation of the Active Principles of an Extract from Valeriana Wallichii Rhizomes

ANTILEISHMANIAL COMPOUNDS FROM NATURE - ELUCIDATION OF THE ACTIVE PRINCIPLES OF AN EXTRACT FROM VALERIANA WALLICHII RHIZOMES Dissertation zur Erlangung des naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorgrades der Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg vorgelegt von Jan Glaser aus Hammelburg Würzburg 2015 ANTILEISHMANIAL COMPOUNDS FROM NATURE - ELUCIDATION OF THE ACTIVE PRINCIPLES OF AN EXTRACT FROM VALERIANA WALLICHII RHIZOMES Dissertation zur Erlangung des naturwissenschaftlichen Doktorgrades der Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg vorgelegt von Jan Glaser aus Hammelburg Würzburg 2015 Eingereicht am ....................................... bei der Fakultät für Chemie und Pharmazie 1. Gutachter Prof. Dr. Ulrike Holzgrabe 2. Gutachter ........................................ der Dissertation 1. Prüfer Prof. Dr. Ulrike Holzgrabe 2. Prüfer ......................................... 3. Prüfer ......................................... des öffentlichen Promotionskolloquiums Datum des öffentlichen Promotionskolloquiums .................................................. Doktorurkunde ausgehändigt am .................................................. "Wer nichts als Chemie versteht, versteht auch die nicht recht." Georg Christoph Lichtenberg (1742-1799) DANKSAGUNG Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde am Institut für Pharmazie und Lebensmittelchemie der Bayerischen Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg auf Anregung und unter Anleitung von Frau Prof. Dr. Ulrike Holzgrabe und finanzieller Unterstützung der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 630) angefertigt. Ich -

CDFG Natural Communities List

Department of Fish and Game Biogeographic Data Branch The Vegetation Classification and Mapping Program List of California Terrestrial Natural Communities Recognized by The California Natural Diversity Database September 2003 Edition Introduction: This document supersedes all other lists of terrestrial natural communities developed by the Natural Diversity Database (CNDDB). It is based on the classification put forth in “A Manual of California Vegetation” (Sawyer and Keeler-Wolf 1995 and upcoming new edition). However, it is structured to be compatible with previous CNDDB lists (e.g., Holland 1986). For those familiar with the Holland numerical coding system you will see a general similarity in the upper levels of the hierarchy. You will also see a greater detail at the lower levels of the hierarchy. The numbering system has been modified to incorporate this richer detail. Decimal points have been added to separate major groupings and two additional digits have been added to encompass the finest hierarchal detail. One of the objectives of the Manual of California Vegetation (MCV) was to apply a uniform hierarchical structure to the State’s vegetation types. Quantifiable classification rules were established to define the major floristic groups, called alliances and associations in the National Vegetation Classification (Grossman et al. 1998). In this document, the alliance level is denoted in the center triplet of the coding system and the associations in the right hand pair of numbers to the left of the final decimal. The numbers of the alliance in the center triplet attempt to denote relationships in floristic similarity. For example, the Chamise-Eastwood Manzanita alliance (37.106.00) is more closely related to the Chamise- Cupleaf Ceanothus alliance (37.105.00) than it is to the Chaparral Whitethorn alliance (37.205.00). -

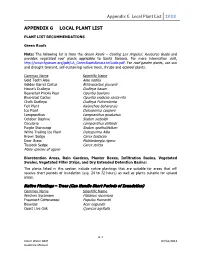

Appendix G Local Plant List 2013 APPENDIX

Appendix G Local Plant List 2013 APPENDIX G LOCAL PLANT LIST PLANT LIST RECOMMENDATIONS Green Roofs Note: The following list is from the Green Roofs – Cooling Los Angeles: Resource Guide and provides vegetated roof plants applicable to Santa Barbara. For more information visit, http://www.fypower.org/pdf/LA_GreenRoofsResourceGuide.pdf. For roof garden plants, use sun and drought tolerant, self-sustaining native trees, shrubs and ecoroof plants. Common Name Scientific Name Gold Tooth Aloe Aloe nobilis Golden Barrel Cactus Echinocactus grusonii Hasse’s Dudleya Dudleya hassei Beavertail Prickly Pear Opuntia basilaris Blue-blad Cactus Opuntia violacea santa-rita Chalk Dudleya Dudleya Pulverulenta Felt Plant Kalanchoe beharensis Ice Plant Delosperma cooperii Lampranthus Lampranthus productus October Daphne Sedum sieboldii Oscularia Lampranthus deltoids Purple Stonecrop Sedum spathulifolium White Trailing Ice Plant Delosperma Alba Brown Sedge Carex testacea Deer Grass Muhlenbergia rigens Tussock Sedge Carex stricta Many species of agave Bioretention Areas, Rain Gardens, Planter Boxes, Infiltration Basins, Vegetated Swales, Vegetated Filter Strips, and Dry Extended Detention Basins: The plants listed in this section include native plantings that are suitable for areas that will receive short periods of inundation (e.g. 24 to 72 hours) as well as plants suitable for upland areas. Native Plantings – Trees (Can Handle Short Periods of Inundation) Common Name Scientific Name Western Sycamore Platanus racemosa Freemont Cottonwood Populus fremontii -

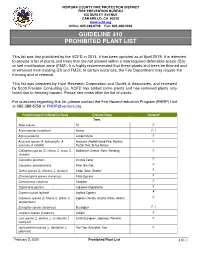

Guideline 410 Prohibited Plant List

VENTURA COUNTY FIRE PROTECTION DISTRICT FIRE PREVENTION BUREAU 165 DURLEY AVENUE CAMARILLO, CA 93010 www.vcfd.org Office: 805-389-9738 Fax: 805-388-4356 GUIDELINE 410 PROHIBITED PLANT LIST This list was first published by the VCFD in 2014. It has been updated as of April 2019. It is intended to provide a list of plants and trees that are not allowed within a new required defensible space (DS) or fuel modification zone (FMZ). It is highly recommended that these plants and trees be thinned and or removed from existing DS and FMZs. In certain instances, the Fire Department may require the thinning and or removal. This list was prepared by Hunt Research Corporation and Dudek & Associates, and reviewed by Scott Franklin Consulting Co, VCFD has added some plants and has removed plants only listed due to freezing hazard. Please see notes after the list of plants. For questions regarding this list, please contact the Fire Hazard reduction Program (FHRP) Unit at 085-389-9759 or [email protected] Prohibited plant list:Botanical Name Common Name Comment* Trees Abies species Fir F Acacia species (numerous) Acacia F, I Agonis juniperina Juniper Myrtle F Araucaria species (A. heterophylla, A. Araucaria (Norfolk Island Pine, Monkey F araucana, A. bidwillii) Puzzle Tree, Bunya Bunya) Callistemon species (C. citrinus, C. rosea, C. Bottlebrush (Lemon, Rose, Weeping) F viminalis) Calocedrus decurrens Incense Cedar F Casuarina cunninghamiana River She-Oak F Cedrus species (C. atlantica, C. deodara) Cedar (Atlas, Deodar) F Chamaecyparis species (numerous) False Cypress F Cinnamomum camphora Camphor F Cryptomeria japonica Japanese Cryptomeria F Cupressocyparis leylandii Leyland Cypress F Cupressus species (C.