Perspectives on Satyajit Ray's Charulata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celebrating the Birth Centenary of Shri Satyajit Ray (2Nd May, 1921- 23Rd April, 1992)

Ministry of Information & Broadcasting Celebrating the Birth Centenary of Shri Satyajit Ray (2nd May, 1921- 23rd April, 1992) Year-long celebrations in India and abroad “Satyajit Ray Lifetime Achievement Award for Excellence in Cinema” instituted Posted On: 30 APR 2021 6:41PM by PIB Delhi In homage to the legendary filmmaker, the Ministry of Information & Broadcasting will organise year-long centenary celebrations of late Shri Satyajit Ray across India and abroad. Shri Satyaji Ray was a renowned filmmaker, writer, illustrator, graphic designer, music composer. He started his career in advertising and found inspiration for his first film, Pather Panchali, while illustrating the children’s version of the novel by Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay. The film catapulted him into international fame. Shri Ray went on to make other great films such as Charulata, Agantuk and Nayak. He was also a prolific writer, making the famous sleuth Feluda and scientist Professor Shonku, a popular part of Bengali Literature. The Government of India honoured him with the Bharat Ratna, the highest civilian award, in 1992. As part of the celebrations, the Media Units of Ministry of Information & Broadcasting viz. Directorate of Film Festivals, Films Division, NFDC, NFAI, and Satyajit Ray Film and Television Institute (SRFTI), Kolkata are planning a series of activities. Other Ministries/Departments including Ministry of External Affairs and Ministry of Culture will also be playing an active part. However, in view of the pandemic situation, the celebrations will be held in hybrid mode, digital and physical both, during the year. In recognition of the auteur’s legacy, “Satyajit Ray Lifetime Achievement Award for Excellence in Cinema” has been instituted from this year to be given at the International Film Festival of India (IFFI) every year starting from this year. -

POWERFUL and POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS in SATYAJIT RAY's FILMS by DEB BANERJEE Submitted to the Graduate Degree Program in Fi

POWERFUL AND POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS IN SATYAJIT RAY’S FILMS BY DEB BANERJEE Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts ____________________ Chairperson Committee members* ____________________* ____________________* ____________________* ____________________* Date defended: ______________ The Thesis Committee of Deb Banerjee certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: POWERFUL AND POWERLESS: POWER RELATIONS IN SATYAJIT RAY’S FILMS Committee: ________________________________ Chairperson* _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Date approved:_______________________ ii CONTENTS Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….. 1 Introduction……………………………………………………………………….... 2 Chapter 1: Political Scenario of India and Bengal at the Time Periods of the Two Films’ Production……………………………………………………………………16 Chapter 2: Power of the Ruler/King……………………………………………….. 23 Chapter 3: Power of Class/Caste/Religion………………………………………… 31 Chapter 4: Power of Gender……………………………………………………….. 38 Chapter 5: Power of Knowledge and Technology…………………………………. 45 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………. 52 Work Cited………………………………………………………………………... 55 i Abstract Scholars have discussed Indian film director, Satyajit Ray’s films in a myriad of ways. However, there is paucity of literature that examines Ray’s two films, Goopy -

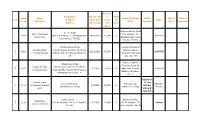

Comp. Sl. No Name S/D/W/O Designation & Office Address Date of First Application (Receving) Basic Pay / Pay in Pay Band Type

Basic Pay Designation Date of First / Type Comp. Name Name & Address Roster Date of Date of Sl. No. & Office Application Pay in of Status Sl. No S/D/W/O D.D.O. Category Birth Retirement Address (Receving) Pay Flat Band Accounts Officer, 9D & Gr. - II Sister Smt. Anita Biswas B.G. Hospital , 57, 1 1879 9D & B.G. Hospital , 57, Beleghata Main 28/12/2012 21,140 A ALLOTTED Sri Salil Dey Beleghata Main Road, Road, Kolkata - 700 010 Kolkata - 700 010 District Fishery Officer Assistant Director of Bikash Mandal O/O the Deputy Director of Fisheries, Fisheries, Kolkata 2 1891 31/12/2012 22,500 A ALLOTTED Lt. Joydev Mandal Kolkata Zone, 9A, Esplanade East, Kol - Zone, 9A, Esplanade 69 East , Kol - 69 Asstt. Director of Fishery Extn. Officer Fisheries, South 24 Swapan Kr. Saha O/O The Asstt. Director of Fisheries 3 1907 1/1/2013 17,020 A Pgns. New Treasury ALLOTTED Lt. Basanta Saha South 24 Pgs., Alipore, New Treasury Building (6th Floor), Building (6th Floor), Kol - 27 Kol - 27 Eligible for Samapti Garai 'A' Type Assistant Professor Principal, Lady Allotted '' 4 1915 Sri Narayan Chandra 2/1/2013 20,970 A flats but Lady Brabourne College Brabourne College B'' Type Garai willing 'B' Type Flat Staff Nurse Gr. - II Accounts Officer, Lipika Saha 5 1930 S.S.K.M. Hospital , 244, A.J.C. Bose Rd. , 4/1/2013 16,380 A S.S.K.M. Hospital , 244, Allotted Sanjit Kumar Saha Kol -20 A.J.C. Bose Rd. , Kol -20 Basic Pay Designation Date of First / Type Comp. -

Rabindranath Tagore: a Social Thinker and an Activist a Review of Literature and a Bibliography Kumkum Chattopadhyay, Retd

2018 Heritage Vol.-V Rabindranath Tagore: a Social Thinker and an Activist A Review of Literature and a Bibliography Kumkum Chattopadhyay, Retd. Associate Professor, Dept. of Political Science, Bethune College, Kolkata-6 Abstract: Rabindranath Tagore, although basically a poet, had a multifaceted personality. Among his various activities his sincerity as a social thinker and activist attract our attention. But this area is till now comparatively unexplored. Many scholars in this area have tried to study Tagore as a social thinker. But so far the findings are scattered and on the whole there is no comprehensive analysis in the strict sense of the term. Hence it is necessary to collect the different findings and to integrate and arrange them within a theoretical framework. This article is an attempt to make a review of literature of the existing books and to prepare a short but sharp bibliography to introduce the area. Key words: Rabindranath Tagore, society, social, political, history, education, Santiniketan, Visva-Bharati Rabindranath Tagore (1861 – 1941) was a prolific writer, a successful music composer, a painter, an actor, a drama director and what not. Besides these talents, he was also a social activist and contributed a lot to Indian social and political thought, although this area has not been very much explored till now. Tagore was emphatic upon society building. So he tried to develop all the component elements which were essential for developing the Indian society. He studied the history of India to follow the trend of its evolution. Next he prepared his programme of action – rural reconstruction and spread of education. -

Letter Correspondences of Rabindranath Tagore: a Study

Annals of Library and Information Studies Vol. 59, June 2012, pp. 122-127 Letter correspondences of Rabindranath Tagore: A Study Partha Pratim Raya and B.K. Senb aLibrarian, Instt. of Education, Visva-Bharati, West Bengal, India, E-mail: [email protected] b80, Shivalik Apartments, Alakananda, New Delhi-110 019, India, E-mail:[email protected] Received 07 May 2012, revised 12 June 2012 Published letters written by Rabindranath Tagore counts to four thousand ninety eight. Besides family members and Santiniketan associates, Tagore wrote to different personalities like litterateurs, poets, artists, editors, thinkers, scientists, politicians, statesmen and government officials. These letters form a substantial part of intellectual output of ‘Tagoreana’ (all the intellectual output of Rabindranath). The present paper attempts to study the growth pattern of letters written by Rabindranath and to find out whether it follows Bradford’s Law. It is observed from the study that Rabindranath wrote letters throughout his literary career to three hundred fifteen persons covering all aspects such as literary, social, educational, philosophical as well as personal matters and it does not strictly satisfy Bradford’s bibliometric law. Keywords: Rabindranath Tagore, letter correspondences, bibliometrics, Bradfords Law Introduction a family man and also as a universal man with his Rabindranath Tagore is essentially known to the many faceted vision and activities. Tagore’s letters world as a poet. But he was a great short-story writer, written to his niece Indira Devi Chaudhurani dramatist and novelist, a powerful author of essays published in Chhinapatravali1 written during 1885- and lectures, philosopher, composer and singer, 1895 are not just letters but finer prose from where innovator in education and rural development, actor, the true picture of poet Rabindranath as well as director, painter and cultural ambassador. -

Artist Recreates Satyajit Ray S Film Posters on 100Th Birth Anniversary

Artist recreates Satyajit Ray's film posters on 100th birth anniversary to depict Covid crisis An artist marked 100 years of legendary filmmaker Satyajit Ray by recreating his iconic film posters to depict the Covid-19 crisis in India. Krishna Priya Pallavi Writer [email protected] If I am not writing on fashion, places you can travel to for that perfect holiday, mental health, trending topics, I am probably escaping the city for a vacation, eating a scrumptious meal at a quaint cafe, and so much more in between. Love to travel (obviously), dance, explore new places, read extensively and try out new and exciting dishes. Works as Senior Sub-Editor at India Today Digital. Aniket Mitra used posters from Satyajit Ray's iconic films to depict the Covid-19 crisis going on in India Photo: Facebook/Aniket Mitra Satyajit Ray had an inedible mark on the Indian cinema. His films are admired by cinephiles all over the world. May 2 marks 100 years since Satyajit Ray was born, and to celebrate his 100th birth anniversary, an artist paid the legendary filmmaker a poignant and relevant tribute. A Mumbai-based artist named Aniket Mitra celebrated the historic day by reimagining Satyajit Ray's iconic film posters amid the Covid times. ARTIST RECREATES SATYAJIT RAY'S FILM POSTERS TO DEPICT COVID CRISIS Aniket Mitra used ten films by Satyajit Ray to depict the Covid-19 crisis going on in India. Posters of films like Pather Panchali, Devi, Nayak, Seemabaddha, Jana Aranya, Mahanagar, Ashani Sanket and more, were used to show the citizens' struggle during the second wave of the deadly virus. -

Rabindranath Tagore's Model of Rural Reconstruction: a Review

[ VOLUME 5 I ISSUE 4 I OCT.– DEC. 2018] E ISSN 2348 –1269, PRINT ISSN 2349-5138 Rabindranath Tagore’s Model of Rural Reconstruction: A review Dr. Madhumita Chattopadhyay Assistant Professor in English, B.Ed. Department, Gobardanga Hindu College (affiliated to West Bengal State University), P.O. Khantura, Dist- 24 Parganas North, West Bengal, PIN – 743273. Received: July 07, 2018 Accepted: August 17, 2018 ABSTRACT Rabindranath Tagore’s unique venture on rural reconstruction at Silaidaha-Patisar and at Sriniketan was a pioneering work carried out by him with the motto of the wholesome development of the community life of village people through education, training, healthcare, sanitation, modern and scientific agricultural production, revival of traditional arts and crafts and organizing fairs and festivities in daily life. He believed that through self-help, self-initiation and self-reliance, village people will be able to help each other in their cooperative living and become able to prepare the ground work for building the nation as an independent country in the true sense. His model of rural reconstruction is the torch-bearer of so many projects in independent India. His principles associated with this programme are still relevant in the present day world, but is not out of criticism. The need is to make critical analysis and throw new lights on this esteemed model so that new programmes can be undertaken based on this to achieve ‘life in its completeness’ among rural population in India. Keywords: Rural reconstruction, cooperative effort, community development. Introduction Rathindranath Tagore once said, his father was “a poet who was an indefatigable man of action” and “his greatest poem is the life he has lived”. -

The 157Th Birthday of Rabindranath COMMEMORATING Tagore, Nobel

Assembly Resolution No. 1257 BY: M. of A. Fernandez COMMEMORATING the 157th Birthday of Rabindranath Tagore, Nobel Laureate of India on Monday May 7, 2018, in New York City WHEREAS, The true architects of society and community are those extraordinary individuals whose faith and unremitting commitment have served to sustain the spiritual and cultural values of life; Rabindranath Tagore, the first Nobel Laureate of Asia was undoubtedly such an individual; and WHEREAS, Attendant to such concern, and in full accord with its long-standing traditions, this Legislative Body is justly proud to commemorate the 157th Birthday of Rabindranath Tagore, Nobel Laureate of India on Monday, May 7, 2018, in New York City; and WHEREAS, Born on May 7, 1861, in Calcutta, India, Rabindranath Tagore was the youngest son of Debendranath Tagore, a leader of the Brahmo Samaj, which was a new religious sect in 19th Century Bengal; and WHEREAS, Rabindranath Tagore was an Indian/Bengali poet, philosopher, novelist, visual artist, playwright, composer and Indian public figure; his works transformed Bengali literature and music in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries; through his works he vigorously influenced the development of Bengali as a literary language, elevating its poetry with new forms and meters; and WHEREAS, Rabindranath Tagore was educated at home; at age 17, he was sent abroad to England for formal schooling, but he did not complete his studies there; and WHEREAS, In his mature years, in addition to his many-sided literary activities, Rabindranath Tagore -

L'adieu a La Vie, 130 Alice in Wonderland, 33 Amiel's Journal, 33

Index Abbott, Lyman, 16 Bauls,46 Achebe, Chinua, 141 Bedford Chapel, Bloomsbury, 11 L'Adieu ala Vie, 130 Beerbohm, Max, 18 African writers, 143 Bengal, 12, 13, 26, 27, 28, 51, 84, 88, Ajanta Cave paintings, 8, 113 100, 110, 145 Agriculture, 96 Bengal Academy, 145 Ahmedabad, 30 Bengal partition, 17 AJfano, Franco, 123 Bengal Renaissance, 50, 51, 52, 54 AJhambra Theatre, London, 123, Bengali language, 1, 8, 13, 27, 29, 35, 127 36,42,142 Alice in Wonderland, 33 Bengali literature, 3, 8, 9, 11, 14,29, Amiel's Journal, 33 33,35,36,37,38,39,42,114 Amritsar massacre, 128 Benjamin, Walter, 109 see also Jalianwalla Bagh Beowulf, 35 massacre, Berg,AJban, 131, 132, 133 Andersen, Hans Christian, 30 Berhampore Gessore), 27 Andrews, C. F., 63, 96, 99 Berlin, 133 Anderson, James Drummond, 8 Berlin Exhibition of Tagore's art, The Arabian Nights, 30, 79, 122 108 Argentina, 97 Bhanaphul (Wild Flower), 52 Aristotle, 38 Bhanusinha (pen-name of Aronson,AJex,l04 Rabindranath Tagore), 27 Art deco, 110 Bhiirati (Bengali journal), 31, 52 Art nouveau, 110 Bharatvasher Itihasha Dhara (A Vision The Artist, 115 of India's History), 58, 59 Asian languages, 142 Bhartrhari, 124 Asian literature, 143 Bhiisa Katha, 42 Asian Review, 20 Bhattacharya, Upendranath, 43 The Athenaeum (journal), 6, 17 Bidou, Henri, 106, 107 Attenborough, Richard, 153 Birdwood, Sir George, 7, 8 Aurobindo Ghose, 50 Birmingham Exhibition of Tagore's Art, 106 Bach, J. S., 106 Bisarjan (Sacrifice), 143 Baines, William, 127 see also Sacrifice Balak (Bengali journal), 31, 32 Blake, William, 6 Balej, -

Lions Film Awards 01/01/1993 at Gd Birla Sabhagarh

1ST YEAR - LIONS FILM AWARDS 01/01/1993 AT G. D. BIRLA SABHAGARH LIST OF AWARDEES FILM BEST ACTOR TAPAS PAUL for RUPBAN BEST ACTRESS DEBASREE ROY for PREM BEST RISING ACTOR ABHISEKH CHATTERJEE for PURUSOTAM BEST RISING ACTRESS CHUMKI CHOUDHARY for ABHAGINI BEST FILM INDRAJIT BEST DIRECTOR BABLU SAMADDAR for ABHAGINI BEST UPCOMING DIRECTOR PRASENJIT for PURUSOTAM BEST MUSIC DIRECTOR MRINAL BANERJEE for CHETNA BEST PLAYBACK SINGER USHA UTHUP BEST PLAYBACK SINGER AMIT KUMAR BEST FILM NEWSPAPER CINE ADVANCE BEST P.R.O. NITA SARKAR for BAHADUR BEST PUBLICATION SUCHITRA FILM DIRECTORY SPECIAL AWARD FOR BEST FILM PREM TELEVISION BEST SERIAL NAGAR PARAY RUP NAGAR BEST DIRECTOR RAJA SEN for SUBARNALATA BEST ACTOR BHASKAR BANERJEE for STEPPING OUT BEST ACTRESS RUPA GANGULI for MUKTA BANDHA BEST NEWS READER RITA KAYRAL STAGE BEST ACTOR SOUMITRA CHATTERHEE for GHATAK BIDAI BEST ACTRESS APARNA SEN for BHALO KHARAB MAYE BEST DIRECTOR USHA GANGULI for COURT MARSHALL BEST DRAMA BECHARE JIJA JI BEST DANCER MAMATA SHANKER 2ND YEAR - LIONS FILM AWARDS 24/12/1993 AT G. D. BIRLA SABHAGARH LIST OF AWARDEES FILM BEST ACTOR CHIRANJEET for GHAR SANSAR BEST ACTRESS INDRANI HALDER for TAPASHYA BEST RISING ACTOR SANKAR CHAKRABORTY for ANUBHAV BEST RISING ACTRESS SOMA SREE for SONAM RAJA BEST SUPPORTING ACTRESS RITUPARNA SENGUPTA for SHWET PATHARER THALA BEST FILM AGANTUK OF SATYAJIT ROY BEST DIRECTOR PRABHAT ROY for SHWET PATHARER THALA BEST MUSIC DIRECTOR BABUL BOSE for MON MANE NA BEST PLAYBACK SINGER INDRANI SEN for SHWET PATHARER THALA BEST PLAYBACK SINGER SAIKAT MITRA for MISTI MADHUR BEST CINEMA NEWSPAPER SCREEN BEST FILM CRITIC CHANDI MUKHERJEE for AAJKAAL BEST P.R.O. -

The Character of Bimala in Tagore's the Home and the World Bimala Is

The character of Bimala in Tagore’s The Home and the World Bimala is a rare portrayal of womanhood by Rabindranath Tagore because unlike the other female characters in Indian literature, there are two sides of Bimala. She is obligated to serve her husband and take care of the household. Yet, she is also willing to overstep these boundaries to speak out for her people. This fact is what makes her a positive representation of women in The Home and the World. Bimala in Tagore’s The Home and the World is perhaps the liveliest character of the story. She is the centre of action as well as attraction of the novel. She emblematizes love amid the fire and fury of politics, and her psychological intricacy contributes much in making Tagore's novel an interesting study. Tagore's Bimala is not a paragon of beauty. She herself admits in the course of the novel that, she had a dark complexion and lacked physical beauty. Yet she was fortunate enough to get married into the Zamindar's house. Bimala was married to Nikhil because of some good astrological signs in her and it was predicted that she would turn out to be an ideal wife. Truly Bimala's conjugal life with Nikhil was happy and blissful. She was fortunate too, to have an ideal, loving husband who unlike his brothers was not authoritarian. She could have from Nikhil not only sincere love but earnest help to make herself a cultivated, advanced modern woman. Arrangements were made for her English training under one European woman, Miss Gilby, and that was quite surprising in an old, conservative family. -

Beyond the World of Apu: the Films of Satyajit Ray'

H-Asia Sengupta on Hood, 'Beyond the World of Apu: The Films of Satyajit Ray' Review published on Tuesday, March 24, 2009 John W. Hood. Beyond the World of Apu: The Films of Satyajit Ray. New Delhi: Orient Longman, 2008. xi + 476 pp. $36.95 (paper), ISBN 978-81-250-3510-7. Reviewed by Sakti Sengupta (Asian-American Film Theater) Published on H-Asia (March, 2009) Commissioned by Sumit Guha Indian Neo-realist cinema Satyajit Ray, one of the three Indian cultural icons besides the great sitar player Pandit Ravishankar and the Nobel laureate Rabindra Nath Tagore, is the father of the neorealist movement in Indian cinema. Much has already been written about him and his films. In the West, he is perhaps better known than the literary genius Tagore. The University of California at Santa Cruz and the American Film Institute have published (available on their Web sites) a list of books about him. Popular ones include Portrait of a Director: Satyajit Ray (1971) by Marie Seton and Satyajit Ray, the Inner Eye (1989) by Andrew Robinson. A majority of such writings (with the exception of the one by Chidananda Dasgupta who was not only a film critic but also an occasional filmmaker) are characterized by unequivocal adulation without much critical exploration of his oeuvre and have been written by journalists or scholars of literature or film. What is missing from this long list is a true appreciation of his works with great insights into cinematic questions like we find in Francois Truffaut's homage to Alfred Hitchcock (both cinematic giants) or in Andre Bazin's and Truffaut's bio-critical homage to Orson Welles.