Treatment of Sepsis in an Intensive Care Unit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gestational Diabetes

Scan with your smartphone to get an e-version of this leaflet. You might need an app to scan this code. Gestational diabetes Information for women Department of Diabetes Aberdeen Royal Infirmary What is gestational diabetes? Some women develop diabetes during pregnancy. This is called gestational diabetes. Gestational diabetes usually starts in the later stages of pregnancy. It happens when the body can’t control its own blood glucose level (sometimes called the “blood sugar level”). The hormone insulin is responsible for controlling blood glucose levels. The hormones produced during pregnancy block the action of insulin in the body. In women who develop gestational diabetes, there is not enough extra insulin produced to overcome the blocking effect. Gestational diabetes can usually be controlled by changes to your diet but some women may need to take tablets or insulin therapy as well. Why do I need to keep my blood glucose down? It’s important to control the level of glucose in your blood during pregnancy and keep it within the normal range. Normal ranges in pregnancy are: • Fasting - less than 5.5mmol/l • 2 hours after food - less than 7.0mmol/l (up to 35 weeks) • 2 hours after food - less than 8.0mmol/l (over 35 weeks). 1 If there’s too much glucose in your blood, your baby’s body may start to make extra insulin to try to cope with it. This extra insulin can make the baby grow larger, making delivery more difficult and so could cause injury to you and your baby. Also a baby who is making extra insulin may have low blood glucose after they are born, which can affect them in the first few hours of life. -

Turn to Your Dentist

WHEN YOU ARE ILL OR INJURED KNOW WHO TO TURN TO. SELF CARE PHARMACIST GP www.know-who-to-turn-to.com This publication is also available in large print NHS OUT OF OPTICIAN SELF MANAGEMENT and on computer disk. Other formats and HOURS SERVICE OPTOMETRIST languages can be supplied on request. Please call Equality and Diversity on 01224 551116 or 552245 or email [email protected] Ask for publication CGD 150869 December 2015 MINOR DENTIST MENTAL HEALTH INJURIES UNIT SELF CARE 4 - 5 PHARMACIST 6 - 7 WHEN YOU’RE ILL MENTAL HEALTH 8 - 9 GP 10 - 11 OR INJURED KNOW NHS OUT OF HOURS SERVICE 12 - 13 WHO TO TURN TO. SELF MANAGEMENT 14 - 15 www.know-who-to-turn-to.com OPTICIAN / OPTOMETRIST 16 - 17 This booklet has been produced to help you get the right DENTIST 18 - 19 medical assistance when you’re ill or injured. There are ten options to choose from. MINOR INJURIES UNIT 20 - 21 A&E / 999 22 - 23 Going directly to the person with the appropriate skills is important. This can help you to a speedier recovery and makes sure all NHS services are run efficiently. The following sections of this booklet give examples of common conditions, and provide information on who to turn to. Remember, getting the right help is in your hands. So please keep this booklet handy, and you’ll always know who to turn to when you’re ill or injured. Further information on all of the above services can be found at www.know-who-to-turn-to.com HANGOVER. -

Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, Aberdeen, Scotland, United Kingdom

Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, Aberdeen, Scotland, United Kingdom Aberdeen Royal Infirmary opened its doors to its first 4 patients in August 1742, and admitted 21 patients in its first year, tak- ing in people from the Northeast region of Scotland and beyond. The early 1800s saw huge changes take place, including the opening of a dedicated mental health hospital. In 1830, increasing demand on the Infirmary resulted in the construction of the Simpson Pavilion at the Woolmanhill site (top left), accommodating 230 patients. Early cardiology records from 1890 show an unidentified physician diagnosing mitral and aortic stenosis. Aberdeen graduate Augustus Désiré Waller conceptualized and recorded the world’s first ECG in 1887, and the first ECG machine was introduced at Woolmanhill in 1920. The New Aberdeen Royal Infirmary at Foresterhill opened in 1936 (aerial photo, top right), expanding over the last century to become one of the largest hospital complexes in Europe (bottom right). As the main teaching hospital of the University of Aberdeen (world’s fifth-oldest English-speaking University, established 1495), doctors and scientists work closely together in shared facilities. Aberdeen Royal Infirmary is home to many medical discoveries and innovations. In the early 1970s, John Mallard andJim Hutchinson pioneered the design and construction of the world’s first whole body magnetic resonance imaging scanner for clinical use (bottom left). Development of the next generation of the technology (fast field cycling magnetic reso- nance imaging) continues here today. In collaboration with general practitioners, Aberdeen cardiologists pioneered prehospital thrombolysis for acute myocardial infarction in the prepercutaneous intervention era. Dana Dawson, DM, DPhil University of Aberdeen and Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, Scotland Euan Wemyss, BSc (Hons) University of Aberdeen, Scotland. -

NHS Grampian CONSULTANT PSYCHIATRIST

NHS Grampian CONSULTANT PSYCHIATRIST Old Age Psychiatry (sub-specialty: Liaison Psychiatry) VACANCY Consultant in Old Age Psychiatry (sub-specialty: Liaison Psychiatry) Royal Cornhill Hospital, Aberdeen 40 hours per week £80,653 (GBP) to £107,170 (GBP) per annum Tenure: Permanent This post is based at Royal Cornhill Hospital, Aberdeen and applications will be welcomed from people wishing to work full-time or part-time and from established Consultants who are considering a new work commitment. The Old Age Liaison Psychiatry Team provides clinical and educational support to both Aberdeen Royal Infirmary and Woodend Hospital and is seen nationally as an exemplar in service delivery. The team benefits from close working relationships with the 7 General Practices aligned Older Adult Community Mental Health Teams in Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire and senior colleagues in the Department of Geriatric Medicine. The appointees are likely to be involved in undergraduate and post graduate teaching and will be registered with the continuing professional development programme of the Royal College of Psychiatrists. They will also contribute to audit, appraisal, governance and participate in annual job planning. There are excellent opportunities for research. Applicants must have full GMC registration, a licence to practise and be eligible for inclusion in the GMC Specialist Register. Those trained in the UK should have evidence of higher specialist training leading to a CCT in Old Age Psychiatry or eligibility for specialist registration (CESR) or be within -

Specialist Radiographer MRI Band 6 £30,401 - £38,046 Per Annum, Full-Time 37.5 Hours Per Week

Aberdeen Royal Infirmary and Woodend Hospital, Aberdeen Specialist Radiographer MRI Band 6 £30,401 - £38,046 per annum, Full-time 37.5 hours per week NHS Grampian are seeking an enthusiastic, flexible and motivated Aberdeenshire boasts many picturesque towns and villages within Radiographer to come and join our friendly MRI team, working across easy commuting distance and provides access to a large range of both Aberdeen Royal Infirmary and Woodend Hospital in Aberdeen. outdoor pursuits including skiing. MRI experience is essential, although full training will be given. There are excellent transport links with Glasgow and Edinburgh CPD is actively encouraged and supported. easily accessed by train and Aberdeen airport has multiple flights to The MRI service currently has 2 Siemens Avanto 1.5T scanners and London daily and other destinations across Europe. Assistance with a GE 450 widebore scanner, with further MRI scanners planned for relocation may be available. the Elective Care Centre and Baird Women’s and Children Hospital in Informal enquiries to Rachel Watt, Lead MRI Superintendent on the future. The NHS also has access to a 3T Philips Achieva research 01224 556881. scanner. Apply by visiting: https://apply.jobs.scot.nhs.uk and search for Both sites are very busy and offer an interesting case mix. Ref No BC012032. Closing date 26th February 2020. We currently operate an extended working day, including evening and weekend shifts and have an MRI On-Call service, which may develop to 24/7 cover. Participation in these is essential. NHS Grampian provides healthcare for a population of 540,000 with around 40% living within Aberdeen and the remaining 60% in Aberdeenshire and Moray. -

“The Joint Hospitals Scheme”

“The Joint Hospitals Scheme” In 2020 NHS Grampian and Grampian Hospitals Art Trust (GHAT) are celebrating the centenary of the formal announcement of the creation of the “Joint Hospitals Scheme”. The scheme innovatively sought to combine public health services and medical education in one location and ultimately resulted in the co-location of Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, Royal Aberdeen Children’s Hospital and Aberdeen Maternity Hospital as well as Aberdeen University Medical School on the Foresterhill campus. The “Joint Hospitals Scheme” was a visionary plan conceived of primarily by Matthew Hay, a Professor of Medical Jurisprudence and Chief Medical Officer of Health for Aberdeen from 1888 to 1923. Hay was concerned about the poor, inadequate and out-dated health care provision in Aberdeen where there existed a growing demand and need for quality health services. He strongly believed by combining the primary hospitals in one location that Aberdeen could build a health care system fit for purpose and able to cope with the changing demands of the new century. Matthew Hay At the turn of the twentieth century the three primary hospitals in Aberdeen were based in separate and cramped facilities in the city centre. The Aberdeen Royal Infirmary was based at Woolmanhill where there was no room to expand and grow services whilst the Aberdeen Maternity, previously a part of the Aberdeen Dispensary, Vaccine and Lying In Institution on Barnett’s Close, had recently moved into a new but still small location at 35 Castle Street in 1900. The Royal Sick Children’s Hospital was located nearby also in a small facility on Castle Terrace. -

NHS Grampian Consultant Anaesthetist (Interest in General Anaesthesia)

NHS Grampian CONSULTANT ANAESTHETIST (Interest in General Anaesthesia) Aberdeen Royal Infirmary VACANCY Consultant Anaesthetist (Interest in General Anaesthesia) Aberdeen Royal Infirmary 40 hours per week £80,653 (GBP) to £107,170 (GBP) per annum Tenure: Permanent NHS Grampian Facilities NHS Grampian’s Acute Sector comprises, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary (ARI), Royal Aberdeen Children’s Hospital (RACH), Aberdeen Maternity Hospital (AMH), Woodend Hospital, Cornhill Hospital, and Roxburgh House, all in Aberdeen and Dr Gray’s Hospital, Elgin. Aberdeen Royal Infirmary (ARI) The ARI is the principal adult acute teaching hospital for the Grampian area. It has a complement of approximately 800 beds and houses all major surgical and medical specialties. Most surgical specialties along with the main theatre suite, surgical HDU, and ICU are located within the pink zone of the ARI. The new Emergency Care Centre (see below) is part of ARI and is located centrally within the site. Emergency Care Centre (ECC) The ECC building was opened in December 2012 and houses the Emergency Department (ED), Acute Medical Initial Assessment (AMIA) unit, primary care out-of- hours service (GMED), NHS24, and most medical specialties of the Foresterhill site. The medical HDU (10 beds), Coronary Care Unit, and the GI bleeding unit are also located in the same building. Intensive Care Medicine and Surgical HDU The adult Intensive Care Unit has 16 beds and caters for approximately 700 admissions a year of which, less than 10 per cent are elective and 14 per cent are transfers from other hospitals. The new 18 bedded surgical HDU together with ICU and medical HDU have recently merged under one critical care directorate. -

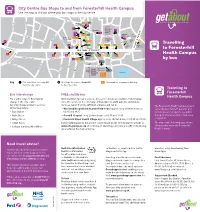

Travelling to Foresterhill Health Campus by Bus Travelling to Aberdeen Royal Infirmary by Bus

Travelling to Foresterhill Health Campus by bus Travelling to Aberdeen Royal Infirmary by bus The Foresterhill Health Campus is well served by bus. All staff, patients and visitors are encouraged to use public transport where possible to help ease congestion. The map on the following page shows all buses that serve the Foresterhill Health Campus. Timetables Tickets You can find full timetable and ticket Tickets can be purchased on bus from information from local travel centres. the driver (cash only), online (Stagecoach tickets) and in travel centres. First Aberdeen – First Travel Centre 47 Union Street, Aberdeen (open For First services you can take 09:00-17:30 Mon-Fri, 09:00-16:30 advantage of their new M-Ticket Sat) or online at www.firstgroup.com/ App which allows you to purchase aberdeen. and download your ticket onto your smartphone to show the driver on Stagecoach Bluebird – boarding. To find out more about this App Union Square Bus Station, Aberdeen go to www.firstgroup.com/aberdeen. (open Mon-Fri 08:00-18:45, Sat 09:00- 17:00 and Sun 10:00-16:00), by phone Travelling from Aberdeenshire on 01224 597591 or online at www. Stagecoach Zone 3 and require to stagecoachbus.com. change buses in the city? Real time information You can purchase the multi-operator Real time information is Grasshopper ticket enabling you to currently available on First bus services. make the whole journey on one ticket. You can check when your bus is due Visit www.grasshopperpass.com for by going to www.realtimebus.com, by more information. -

Aberdeen Royal Infirmary.Pdf

Unit Brief v1 ICM Unit Brief Part 1 Hospital Details 1.1 Hospital name Aberdeen Royal Infirmary 1.2 Full address (you must include postcode) 1.3 Hospital Telephone number Aberdeen Royal Infirmary 0345 456 6000 Foresterhill Health Campus Foresterhill Road Aberdeen AB25 2ZN Part 2 ICU Department contact details 2.1 Direct telephone number to Department 01224 554253 2.2 Faculty Tutor name 2.3 Faculty Tutor Email address Paul Gamble [email protected] Part 3 Unit Structure 3.1 Number of Beds 3.2 Number of admissions 24 1200 3.3 Percentage of elective vs emergency admissions 95% emergency admissions 3.4 Overview of case mix within the unit Mixed medical and surgical critical care unit split over 2 sites within Aberdeen Royal Infirmary for level 2 and 3 patients including neurosurgical ICU. We also support elective admissions from major head and neck surgery and major upper GI surgery. Commissioned ECMO centre for Scotland (2019) providing VV ECMO for approximately 25-30 patients per year from across Scotland. Awarded Platinum status by the Extracorporeal Life Support Organisation in recognition of the high level of ECMO care provided. Major trauma centre status from October 2018, serving the North of Scotland. Page 1 (of 3) Unit Brief v1 3.5 Names of Consultants, roles and areas of interest Role (eg clinical lead, Name Areas of Interest consultant) Lee Allen Consultant Critical Care Neuro critical care/Research/FICE mentor Roxanna Bloomfield Consultant Critical Care/ Education/transportation and Anaesthesia/ EMRS retrieval Andrew Clarkin -

VACANCY: Honorary Senior Lecturer University of Aberdeen

Consultant in Palliative Medicine NHS Grampian and VACANCY: Honorary Senior Lecturer University of Aberdeen Looking for a change and a new beginning? Consider working with us in the north of the United in Palliative Care. We are aligned to the acute medical Kingdom with a fulfilling job in an area of outstanding directorate of Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, wholly funded by natural beauty. Working on the doorstep of Royal NHS Grampian and supported by Friends, Endowments Deeside and the Grampian Highlands and working with and Macmillan. You would be one of a team of eight the principal specialist palliative care provider in the doctors (3 consultants, 2 registrars, 2 FY2 doctors and one north of Scotland. Aberdeen has much to commend GP registrar all on 4 month rotation) working with a team itself, offering a vibrant shopping, theatre, restaurant of over 30 nurses with a comprehensive paramedical and and music scene to cater for all tastes. It offers a great therapies team. life style, many areas of housing development both within the city and in a more rural setting to suit your particular needs. There are excellent schools within the About You Being already a specialist in palliative care (or just about area and excellent travel infrastructure on account of to become one), you alredy understand the importance of the oil industry meaning all UK destinations are very being a team player and taking responsibility as and when easily accessible. required. About Us We are more than happy to be as flexible as possible to We are the largest provider of specialist palliative care help you achieve a fulfilling work-life balance and to allow in the north of Scotland and the successful applicant you to develop and nurture your own personal specific would join our excellent team of dedicated and caring skills or interests. -

Writer Final

Writer – Roxburghe House, Aberdeen September 2015 to March 2016 Grampian Hospitals Art Trust (GHAT) is looking for a writer to work with patients, their relatives and staff at Roxburghe House, a specialist palliative care unit in Aberdeen. The role of the writer is to encourage dialogue and to facilitate the sharing of ideas, experiences, memories and stories within the community of Roxburghe House. The present Roxburghe House Writing Project began in July 2012. The current writer has worked alongside the two visual artists at Roxburghe, as well as with other staff in the unit, to offer a range of individual and group creative opportunities. We are now looking for someone to further develop the role. This a demanding post as you will be working with people who have a wide variety of needs and concerns, many of whom face serious emotional and physical difficulties. It is desirable that you are available to work for three days per week and at least one of those days to be Tuesday or Thursday in order to take part in the Day Unit programme Main tasks will include: • Individual sessions with patients and relatives, assisting the creative writing process in ways tailored to their needs – often acting as scribe or as sounding board • Assisting patients and relatives with their own stories and life narratives • Inspiring people who may not think of themselves as creative to share their ideas and stories and to explore writing • Facilitating group work sessions as part of the Day Unit programme and elsewhere • Working closely with the artists and staff at Roxburghe House to initiate and facilitate word-related arts projects • Reading poems and stories to and with patients • Providing literary resources attuned to individual participants’ needs and concerns • Conducting educational sessions with staff • Linking with Friends of Roxburghe House and the wider local community You will be a professional, practising writer, educated to degree level or equivalent, with extensive previous experience of creative writing. -

Travelling to Foresterhill Health Campus by Bus Leaflet

City Centre Bus Stops to and from Foresterhill Health Campus Use the map to find out where your bus stops in the city centre SK ENE ST N L T 37, X37 59 HUN Central HM TLY Library IA S TLE ST Theatre 14 R S This white box THI 3 Bon-Accord U BLACKFRIARSArt ST Gallery 14 and logo must VICTO N Shopping I O Centre 14 SC 14 N H O remain over any T 37, X37 59 O A T E Aberdeen Arts THI S 3 T LH I RK G LL K I B STLE R E U PPER City Council Centre R ST St Mary’s R artwork that is 37, X37 R O HUNTLR.C. Cathedral A St Nicholas 14 C A Police T Centre in this area for T SUMME E 23 THIS S S 37, X37 14 D HQ TLE 8 PL L E Y cover gluing S Travelling OSE S 14 23 T 14 23 3 59 8 23 37, X37 8 23 T Town St Andrew’s R Music House CHAP KINGCathedral STREET ALF Hall ORD to Foresterhill PLACE UNION STREET MARKET STREET T 8 3 59 T 14 23 S Health Campus 14 23 14 23 S 8 14 23 8 8 14 23 N 8 R JUSTICE MILL LANE E Trinity U Mall B LANGSTANE PL 3 37, X37 59 by bus L O IDG 3 59 H R UNION GLEN B GUILD STREET T DEE ST S Aberdeen HARDGATE Union Rail Bus Station 3 59 Station Square Shopping Harbour BON-ACCORD ST CROWN Centre 10, 35 37, X37 Key Bus stops for services to ARI Bus stops for services from ARI 37 Bus numbers stopping at this stop from the city centre to the city centre Travelling to Foresterhill Bus Interchange FREE shuttle bus Health Campus For a wider range of destinations NHS Grampian operates a shuttle bus service between a number of its hospital change in the city centre.