Fèis A' Chaolais

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ardgay District

ARDGAY & DISTRICT Community Council newsletter Price: £1.00 ISSN (Online) 2514-8400 = Issue No. 36 = SUMMER 2017 = New Hub opening this summer The new Kyle of Sutherland Hub is almost com- plete. Here is a taste of what is to come. THE TEAM HAVE BEEN appointed Ann Renouf, Café Supervisor, and we would like to welcome Emma Mackay, General As- Adele Newlands, Hub Manag- sistant, and Clark Goodison, er; Vicky Karl, Café Manager; Cleaner. (Continue on page 9) The bright red Hub, as seen from Tulloch. THE CURRENT CC WAS FORMED IN FEBRUARy 2016 Achievements and challenges of your Community Council from June 2016 WE REPRODUCE Betty the issues discussed at Wright’s annual report our meetings? Which from our AGM. Our will feature in next year’s Chairperson thanks all agendas? We have cre- who have given freely of ated a map highlighting their time to CC business. the work of your CC in (Pages 4-6) What were 2016-2017. (Page 5). Opening of the Falls of Shin Visitor Attraction. The work of the Kyle of Plans to supply access to Sutherland Development Trust Superfast broadband to all Helen Houston reports on current and future projects What to do if you have been ‘left out’ Page 8 of the Trust (Pages 14-15) Beginning of the works on the Business Barn & Art Shed in Ardgay (Page 11) Know more about East Sutherland Energy Advice Service (Page 17) George Farlow’s farewell message Page 7 All you need Volunteering a to know opportunities 32 pages featuring Letters to the Editor, about horses in your Opening times, on the road area Telephone guide, Bus & Train timetable, Page 10 Page 20 Crosswords, Sudoku.. -

Date of Publication: 29 June 2015 Department

Date of publication: 29 June 2015 Department: Community Services Frequency: Annual Contents / Clàr-innse LIST OF TABLES / LIOSTA CHLÀRAN ............................................................................... 3 LIST OF FIGURES / LIOSTA FHIGEARAN .......................................................................... 3 LIST OF APPENDICES / LIOSTA PHÀIPEARAN-TAICE ..................................................... 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY / GEÀRR-CHUNNTAS GNÌOMHACH ............................................ 4 INTRODUCTION / RO-RÀDH ............................................................................................... 6 BENCHMARKING / DEUCHAINN-LUATHAIS ...................................................................... 7 COMMUNITY RE-USE & RECYCLING / ATH-CHLEACHDADH & ATH-CHUAIRTEACHADH COIMHEARSNACHD ............................................................................................................ 9 RECYCLING/COMPOSTING / ATH-CHUAIRTEACHADH/DÈANAMH TODHAR ................ 11 KERBSIDE RECYCLING / ATH-CHUAIRTEACHADH CABHSAIR ................................................... 14 Garden waste service ................................................................................................... 14 Food waste kerbside service ........................................................................................ 16 Comingled kerbside service .......................................................................................... 16 RECYCLING CENTRES & TRANSFER STATIONS / IONADAN ATH-CHUAIRTEACHAIDH -

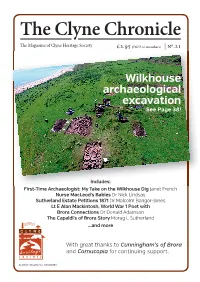

The Clyne Chronicle

The Clyne Chronicle The Magazine of Clyne Heritage Society £2.95 (FREE to members) | Nº.21 Wilkhouse archaeological excavation See Page 38! Includes: First-Time Archaeologist: My Take on the Wilkhouse Dig Janet French Nurse MacLeod's Babies Dr Nick Lindsay Sutherland Estate Petitions 1871 Dr Malcolm Bangor-Jones Lt E Alan Mackintosh, World War 1 Poet with Brora Connections Dr Donald Adamson The Capaldi's of Brora Story Morag L Sutherland …and more With great thanks to Cunningham’s of Brora and Cornucopia for continuing support. Scottish Charity No. SC028193 Contents Comment from the Chair 3 Chronicle News 4 Brora Heritage Centre: the Story of 2017 5 Nurse MacLeod’s Babies! 12 93rd Sutherland Highlanders 1799-1815: The Battle of New Orleans 13 Old Brora Post Cards 19 My Family Ties With Clyne 21 Sutherland Estate Petitions 1871 27 Lt E Alan Mackintosh, World War 1 Poet with Brora Connections 34 The Wilkhouse Excavations, near Kintradwell 38 First-Time Archaeologist: My Take on the Wilkhouse Dig 46 Clyne War Memorial: Centenary Tributes 51 Guided Walk Along the Drove Road from Clynekirkton to Oldtown, Gordonbush, Strath Brora 54 Veteran Remembers 58 The Capaldi's of Brora Story 60 Old Clyne School: The Way Forward 65 More Chronicle News 67 Society Board 2018-19 68 In Memoriam 69 Winter Series of Lectures: 2018-19 70 The Editor welcomes all contributions for future editions and feedback from readers, with the purposes of informing and entertaining readers and recording aspects of the life and the people of Clyne and around. Many thanks to CHS member, Tim Griffiths, for much appreciated technical assistance with the Chronicle and also to all contributors. -

![Inverness County Directory for 1887[-1920.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9656/inverness-county-directory-for-1887-1920-3069656.webp)

Inverness County Directory for 1887[-1920.]

Try "SCOT STILL" Whisky (6 Years I'l'ont '-i.AHK. 1'.! Y..un SfitMl INVERN 'OUNTY DIRECTORY 19 02 - PRICE ONE SHIL.I.INC • jf CO D. PETRIE, Passenger Agent, Books Passengers by the First-Class Steamers to SOU RIGA lA IM III) > I A 1 IS STRAi CANADA INA son in ATUkiCA NEW ZEAI AN And ail Parts of yj^W^M^^ Pn5;scfrj!fef» information as ii. 1 arc iScc, and Booked at 2 L.OMBARD STREET, INVERNESS. THREE LEADING WHISKIES in the NORTH ES B. CLARK, 8. 10, 12. 1* & 16 Young: at., Inv< « « THE - - HIMLAND PODLTRT SUPPLY ASSOCIATION, LIMITED. Fishmongers, Poulterers, and Game Dealers, 40 Castle Street, INVERNESS. Large Consignments of POULTRY, FISH, GAME, &c., Daily. All Orders earefuUy attended to. Depot: MUIRTOWN, CLACHNAHARRY. ESTABLISHED OVER HALP-A-CENTURY. R. HUTCHESON (Late JOHN MACGRBGOR), Tea, 'Mine and kfpirit ^ere^ant 9 CHAPEL STREET INVERNESS. Beep and Stout In Bottle a Speciality. •aOH NOIlVHaiA XNVH9 ^K^ ^O} uaapjsqy Jo q;jON ^uaSy aps CO O=3 (0 CD ^« 1 u '^5 c: O cil Z^" o II K CO v»^3U -a . cz ^ > CD Z o O U fc 00 PQ CO P E CO NORTH BRITISH & MERCANTILE INSURANCE COMPANY. ESTABLISHED 1809. FIRE—K-IFE-ANNUITIES. Total Fwnds exceed «14,130,000 Revenue, lOOO, over «»,06T,933 President-HIS GRACE THE DUKE OF SUTHERLAND. Vice-President—THE MOST HON. THE MARQUESS OF ZETLAND, K.T. LIFE DEPARTMENT. IMPORTANT FEATURES. JLll Bonuses vest on Declaration, Ninety per cent, of Life Profits divided amongst the Assured on the Participating Scale. -

New Series, Volume 19, 2018

NEW SERIES, VOLUME 19, 2018 DISCOVERY AND EXCAVATION IN SCOTLAND A’ LORG AGUS A’ CLADHACH AN ALBAINN NEW SERIES, VOLUME 19 2018 Editor Paula Milburn Archaeology Scotland Archaeology Scotland is a voluntary membership organisation, which works to secure the archaeological heritage of Scotland for its people through education, promotion and support: • education, both formal and informal, concerning Scotland’s archaeological heritage • promotion of the conservation, management, understanding and enjoyment of, and access to, Scotland’s archaeological heritage • support through the provision of advice, guidance, resources and information related to archaeology in Scotland Our vision Archaeology Scotland is the leading independent charity working to inspire people to discover, explore, care for and enjoy Scotland’s archaeological heritage. Our mission …to inspire the discovery, exploration, stewardship and enjoyment of Scotland’s past. Membership of Archaeology Scotland Membership is open to all individuals, local societies and organisations with an interest in Scottish archaeology. Membership benefits and services include access to a network of archaeological information on Scotland and the UK, three newsletters a year, the annual edition of the journal Discovery and excavation in Scotland, and the opportunity to attend Archaeology Scotland’s annual Summer School and the Archaeological Research in Progress conference. Further information and an application form may be obtained from Archaeology Scotland Email [email protected] Website www.archaeologyscotland.org.uk A’ lorg agus a’ cladhach an Albainn The Gaelic translation of Discovery and excavation in Scotland was supplied by Margaret MacIver, Lecturer in Gaelic and Education, and Professor Colm O’Boyle, Emeritus Professor, both at the Celtic, School of Language and Literature, University of Aberdeen. -

Ardgay District

ARDGAY & DISTRICT Community Council newsletter Price: £1.00 ISSN 2514-8400 = Issue No. 42 = WINTER 2018-19 = EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW WITH THE NEW MANAGER OF THE KYLE OF SUTHERLAND DEVELOPMENT TRUST David Watson: “I’m fully committed to the area, I believe it can be a strong sustainable community.” ORIGINALLY FROM ALTASS, Rural De- velopment expert David Watson has worked in places such as the Cairn- gorms National Park, Shetland and Inverness. He is now returning to this area to take on the role of Kyle of Sutherland Development Trust Manager. -How does it feel coming back? -This is very different for me than when I was working in other are- as because there are friends of mine from when I went to Primary School who still live in the area, my moth- er still lives in this area, my auntie lives in this area... I have to answer to those people. -The stakes are higher... -The stakes are much higher. That David Watson (centre) with some of the Kyle of Sutherland Development Trust Team. doesn’t intimidate me, I actually find it a really good challenge. I know able place to move forward. I really stand why we are doing things. It’s that the Trust is not going to be able want to do what is best for the com- easy to see what we are doing, we want to please everybody but we are trying munity and I’m hopeful that we can to be even better in telling people why to do what we think will work for the work with the different communities we are doing things and why it mat- community to make it a more sustain- within our area to help them under- ters to them. -

![Inverness County Directory for 1887[-1920.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4310/inverness-county-directory-for-1887-1920-3494310.webp)

Inverness County Directory for 1887[-1920.]

ONIr. SHIL-ILif^fC,; . PETRI ii>-prs bv thf ESTABLISHED 1852. THE LANCASHIRE IN (FIRE and LIFE) Capital - - Three Millions Sterling. Chief Offices EXCHANGE STREET, IVIANCHESTER Branch Office in Inverness— Lancashire Insurance Buildings, Queen's Gate. SCOT FISH BOAR D— Chas. M. Bkown, Esq., Inverness. W. H. KiDSTON, Esq. Hugh Brown, Esq. Sir James Kin'g of Campsie, Bart., LL.D. David S. Carqill, Esq. Andrew Mackenzie, Esq. of Dalmore. John Cran, Esq., Inverness. Sir Kenneth J. Matheson of Lochalsh, Sir Charles Dalrymple of Newhailes, Bart. Bart., M.P. Alexander Ross, Esq., LL.D., Inverness. Sir George Macpherson- Grant of Sir James A. Russell, LIj.D., Edinburgh. Ballindalloch, Bart. (London Board). Alexander Scott, Esq., J. P., Dundee. FIRE EPARTMEIMT The progress made iu the Pire Department of the Company has been very marked, and is the result of the promptitude with which Claims for loss or damage by Fire have always been met. The utmost Security is afl'orded to Insurers by the ample Capital and large Reserve Fund, in addition to the annual Income from Premiums. Insurances are granted at Moderate Rates upon almost every description of Property. Seven Years' Policies are issued at a charge for Six Years only. Rents Insm-ed at the same rate of Premium as that charged for Buildings, but must have a separate £am placed thereon. Household Insurances. —As it is sometimes inconvenient to specify in detail the contents of dwelling-houses, and to value them separately for Insurance, the '* Lancashire" grants Policies at an annual premium of 2s per cent., covering "Household Goods and Property of every description " in one sum. -

128311826.23.Pdf

( t SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY FOURTH SERIES VOLUME 8 Papers on Sutherland Estate Management Volume i PAPERS ON SUTHERLAND ESTATE MANAGEMENT i802-1816 edited by R. J. Adam, M.A. Volume 1 ★ ★ EDINBURGH printed for the Scottish History Society by T. AND A. CONSTABLE LTD 1972 © Scottish History Society 1972 •$> B 134 FEC x 19 73/ ' SBN 9500260 3 4 (set of two volumes) SBN 9500260 4 2 (this volume) Printed in Great Britain PREFACE The Society’s invitation to edit these volumes came when I was already engaged on a detailed study of the history of the Sutherland Estate in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. That being so, it was necessary to decide on the precise division of material between this work and the book which I hope to publish on the wider aspects of the history of the estate. The decision taken by my fellow-editor, the late Mr A. V. Cole (Senior Lecturer in Economics in the Uni- versity of Leicester, and one-time Lecturer in Political Economy in the University of St Andrews), and myself was to publish evidence which would illustrate the general working of the estate manage- ment, and to concentrate in the introduction, where space was neces- sarily limited, upon the economic aspects of estate policy. It was our intention, on account of our different disciplinary approaches, that I should assume responsibility for selection and textual preparation, while Mr Cole should analyse the material from an economic stand- point and write a major part of the introduction. I was fortunate to have Mr Cole’s help and guidance in the early stages of selection, and to come to know something of his thinking on the broad issues presented by the evidence. -

The Macdonald Ancestors of Susannah Macdonald (Married William Stevenson 1899, Leith)

SECTION 2: The MacDonald Ancestors of Susannah MacDonald (Married William Stevenson 1899, Leith) DRAFT V5 Edited Nathalie Stevenson 23rd December 2014 Please please do send me any comments, add information, point out omissions etc etc. Even just stories/tales would be great – anything! Oral history is more interesting than just dry census records, so please send your tales I really like to add details about the Stewart side of the family too, and not had a chance to speak to the Stewarts of Stornoway yet! Contributors: Susan Dobbie (nee Stevenson) Alasdair Mackenzie Nathalie Stevenson Mary Mackenzie (nee MacDonald) Jimmy MacDonald NB all dates in the this document are presented the English way, i.e. day/month/year Table of Contents SECTION 2: THE MACDONALD/STEWART ANCESTORS (‘MA’) .......................................................................... 5 Introduction......................................................................................................................................................... 5 Scots Nawken ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 Atholl Stewarts, Appin Stewarts and Coigach Stewarts ...................................................................................... 6 Jacobite Rebellions and the Highland Clearances............................................................................................... 8 Searching the records......................................................................................................................................... -

Meall Buidhe, Ardgay, Sutherland Archaeological Walkover Survey Report

Meall Buidhe, Ardgay, Sutherland Archaeological Walkover Survey Report AOC 70240 November 2017 © AOC Archaeology Group 2017 Meall Buidhe, Ardgay, Sutherland Archaeological Walkover Survey Report On Behalf of: Muirden Energy LLP National Grid Reference (NGR): NH 45662 95502 AOC Project No: 70240 Prepared by: L. Fraser Illustrations by: L. Fraser Date of Fieldwork: 20th November 2017 Date of Report: 21st November 2017 OASIS No.: aocarcha1-301741 This document has been prepared in accordance with AOC standard operating procedures. Authors: Lynn Fraser Date: 21st November 2017 Approved by: Mary Peteranna Date: 30th November 2017 Report Stage: Final Date: 30th November 2017 Enquiries to: AOC Archaeology Group The Old Estate Office Rosehaugh Estate Avoch IV9 8RF Mob. 07972 259255 Tel. 01463 819841 E‐mail [email protected] www.aocarchaeology.com 70240: Meall Buidhe, Ardgay, Sutherland, Archaeological Walkover Survey Report Contents Page List of illustrations ............................................................................................................................................................ 2 List of plates ...................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Abstract .............................................................................................................................................................................. 3 1.0 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................... -

New Rogart Cemetery Our Code RO-A

New Rogart Cemetery Our code RO-A Note: this graveyard is still in use. The new cemetery at Rogart lies in the valley opposite the old Kirk of St Callan. It is a very pretty spot and a very well kept cemetery. These are the oldest stones there. Note – we have chosen not to show some stones which record deaths during the last 50 or so years. Some of these stones belong to families who still live in Rogart This is a work in progress and new inscriptions may be added later this year Christine Stokes photographed and transcribed this cemetery. She has a considerable amount of genealogical information on the people of Rogart. If you are researching people from Rogart please feel free to contact her Please note that with all our inscriptions all Mc and Mac names are shown as Mac. This facilitates easier indexing for us and easier searching for you 100 years ago 1905 * * * * ROGART - Some time ago several meetings of the ratepayers were held to consider the condition of the burying ground, and the urgent necessity for its extension or the procuring of new ground. After certain steps had been taken with regard to it, the matter was allowed to fall into abeyance owing, principally, to the impossibility of finding, in a convenient situation, suitable ground for the purpose. Now that a croft in close proximity to the present burying-ground, and suitable in every respect, has become vacant a short time ago, through the surviving tenant having given up her right thereto, the Parish Council has taken the matter seriously in hand and at their meeting on Monday Rev Mr Macdonald, after referring to the present burying-ground, which he characterised as inadequate for the requirements of the parish, as being in a highly unbecoming state, and as an extension was by no means feasible, moved that the requisite steps be taken for the procuring of a new burying-ground. -

Waste Data Report April 2011 – March 2013

Waste Data Report April 2011 – March 2013 May 2015 Contents / Clàr-innse LIST OF TABLES / LIOSTA CHLÀRAN ............................................................................... 3 LIST OF FIGURES / LIOSTA FHIGEARAN .......................................................................... 3 LIST OF APPENDICES / LIOSTA PHÀIPEARAN-TAICE ..................................................... 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY / GEÀRR-CHUNNTAS GNÌOMHACH ............................................ 4 INTRODUCTION / RO-RÀDH ............................................................................................... 5 BENCHMARKING / DEUCHAINN-LUATHAIS ...................................................................... 6 AREA RECYCLING RATES / REATAICHEAN ATH-CHUAIRTEACHAIDH SGÌREIL .............................. 8 COMMUNITY RE-USE & RECYCLING / ATH-CHLEACHDADH & ATH-CHUAIRTEACHADH COIMHEARSNACHD ............................................................................................................ 9 RECYCLING/COMPOSTING / ATH-CHUAIRTEACHADH/DÈANAMH TODHAR ................ 11 KERBSIDE RECYCLING / ATH-CHUAIRTEACHADH CABHSAIR ................................................... 13 Kerbside sort & garden waste services ......................................................................... 13 Comingled kerbside services ........................................................................................ 14 RECYCLING CENTRES & TRANSFER STATIONS / IONADAN ATH-CHUAIRTEACHAIDH & STÈISEANAN GLUASAID ........................................................................................................................