Open Thesis.Draft.V06.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Map of Dolakha District Show Ing Proposed Vdcs for Survey

Annex 3.6 Annex 3.6 Map of Dolakha district showing proposed VDCs for survey Source: NARMA Inception Report A - 53 Annex 3.7 Annex 3.7 Summary of Periodic District Development Plans Outlay Districts Period Vision Objectives Priorities (Rs in 'ooo) Kavrepalanchok 2000/01- Protection of natural Qualitative change in social condition (i) Development of physical 7,021,441 2006/07 resources, health, of people in general and backward class infrastructure; education; (ii) Children education, agriculture (children, women, Dalit, neglected and and women; (iii) Agriculture; (iv) and tourism down trodden) and remote area people Natural heritage; (v) Health services; development in particular; Increase in agricultural (vi) Institutional development and and industrial production; Tourism and development management; (vii) infrastructure development; Proper Tourism; (viii) Industrial management and utilization of natural development; (ix) Development of resources. backward class and region; (x) Sports and culture Sindhuli Mahottari Ramechhap 2000/01 – Sustainable social, Integrated development in (i) Physical infrastructure (road, 2,131,888 2006/07 economic and socio-economic aspects; Overall electricity, communication), sustainable development of district by mobilizing alternative energy, residence and town development (Able, local resources; Development of human development, industry, mining and Prosperous and resources and information system; tourism; (ii) Education, culture and Civilized Capacity enhancement of local bodies sports; (III) Drinking -

Provincial Summary Report Province 3 GOVERNMENT of NEPAL

National Economic Census 2018 GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Economic Census 2018 Provincial Summary Report Province 3 Provincial Summary Report Provincial National Planning Commission Province 3 Province Central Bureau of Statistics Kathmandu, Nepal August 2019 GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Economic Census 2018 Provincial Summary Report Province 3 National Planning Commission Central Bureau of Statistics Kathmandu, Nepal August 2019 Published by: Central Bureau of Statistics Address: Ramshahpath, Thapathali, Kathmandu, Nepal. Phone: +977-1-4100524, 4245947 Fax: +977-1-4227720 P.O. Box No: 11031 E-mail: [email protected] ISBN: 978-9937-0-6360-9 Contents Page Map of Administrative Area in Nepal by Province and District……………….………1 Figures at a Glance......…………………………………….............................................3 Number of Establishments and Persons Engaged by Province and District....................5 Brief Outline of National Economic Census 2018 (NEC2018) of Nepal........................7 Concepts and Definitions of NEC2018...........................................................................11 Map of Administrative Area in Province 3 by District and Municipality…...................17 Table 1. Number of Establishments and Persons Engaged by Sex and Local Unit……19 Table 2. Number of Establishments by Size of Persons Engaged and Local Unit….….27 Table 3. Number of Establishments by Section of Industrial Classification and Local Unit………………………………………………………………...34 Table 4. Number of Person Engaged by Section of Industrial Classification and Local Unit………………………………………………………………...48 Table 5. Number of Establishments and Person Engaged by Whether Registered or not at any Ministries or Agencies and Local Unit……………..………..…62 Table 6. Number of establishments by Working Hours per Day and Local Unit……...69 Table 7. Number of Establishments by Year of Starting the Business and Local Unit………………………………………………………………...77 Table 8. -

WASH Cluster Nepal 4W - May 12Th 2015

WASH Cluster Nepal 4W - May 12th 2015 Please find following the analysis of the 4W data – May 12th Introduction (Round 2) This is the second round of the 4W analysis. As this is the second round and still early in the emergency response, many agencies are still planning their interventions and caseloads, hence much of the data is understandably incomplete. In the coming week/s we will receive far more comprehensive partner data and will be able to show realistic gaps. In addition, we are receiving better affected population data and there are many ongoing assessments, the results of which will help us to understand both the response data and the affected population data and enable us to deliver a far more profound analysis of the WASH response. Please assist us as we have a lot of information gaps in the data provided so far and hence the maps are not yet providing a true picture of the response. We would like to quickly move to VDC mapping including planned/reached beneficiaries. Since the first round of reporting, agencies have provided substantially more VDC‐level data – as of today, of 740 WASH activities identified, 546 of these (74%) are matched to an identified VDC ‐ this is a big improvement from last week (which had VDC data for 192 of 445 activities, or 43%) The Highlights ・ 47 Organisations – number of organisations that reported in Round 1 and/or Round 2 of the WASH 4W ・ 206 VDCs – where WASH interventions taking place/planned (in 15 districts) 4W – WASH May 12th 2015 Water0B Spread of water activities ‐ targeted Temporary -

Organizational Profile-2021

Organizational Profile-2021 Kamalamai,6 Sindhui Email: [email protected] Web: reliefnepal.org.np 1. Organizational Profile 1.1 Organizational General Information S.N Particulars Detail Information 1 Name of the Relief Nepal organization 2 Type of Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) Organization 3 Vision, Mission, Vision: Goal and Objectives Society with social, economic, political and gender equity. Mission: To enhance the livelihoods of children, youth, women and marginalized sections of the society through empowering them to be self-reliant so that ensures their meaningful participation in decision- making process in the society and able to enjoy their rights. Goal: Vulnerable and marginalized people especially women, children, youths and people living with marginalized conditions are empowered and participate in decision making process about the issues affecting their livelihood. Objectives*: i. To conduct coordination, collaboration and advocacy on planning and implementation in the program of local government and related stakeholders for wellbeing of most vulnerable children, ii. To organize, implement and advocate programs for protection and ensure rights of children, women, youths, physically challenged and marginalized groups, iii. To organize, implement and advocate programs on access of water sanitation and hygiene (WASH), education and health facilities to marginalized groups with the related stakeholders, iv. To organize campaign against social mal-practices and 1 superstitions and implement programs to raise awareness, v. To organize and implement programs on economic and social transformation of people to improve livelihood of marginalized people, vi. To organize and implement programs on improved agriculture practices for people below poverty line & marginalized people; support them to improve livelihood via different MSMEs and market promotion through linkages, vii. -

A Case Study of Sindhuli, Nepal Shreyasha Khadka [email protected]

Clark University Clark Digital Commons International Development, Community and Master’s Papers Environment (IDCE) 5-2019 A study on the reflections of women and men on a women’s empowerment project: A case study of Sindhuli, Nepal Shreyasha Khadka [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.clarku.edu/idce_masters_papers Part of the Community-Based Research Commons, Development Studies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Quantitative, Qualitative, Comparative, and Historical Methodologies Commons Recommended Citation Khadka, Shreyasha, "A study on the reflections of women and men on a women’s empowerment project: A case study of Sindhuli, Nepal" (2019). International Development, Community and Environment (IDCE). 229. https://commons.clarku.edu/idce_masters_papers/229 This Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Master’s Papers at Clark Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Development, Community and Environment (IDCE) by an authorized administrator of Clark Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A study on the reflections of women and men on a women’s empowerment project: A case study of Sindhuli, Nepal Shreyasha Khadka (May 2019) A Master’s Paper Submitted to the faculty of Clark University, Worcester, Massachusetts, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the International Development, Community and Environment Department (IDCE) And accepted on the recommendation of Cynthia Caron, Chief Instructor Abstract A study on the reflections of women and men on a women’s empowerment project: A case study of Sindhuli, Nepal Shreyasha Khadka Women empowerment and gender equality are considered key aspects of achieving sustainable development goals. -

S.N Local Government Bodies EN स्थानीय तहको नाम NP District

S.N Local Government Bodies_EN थानीय तहको नाम_NP District LGB_Type Province Website 1 Fungling Municipality फु ङलिङ नगरपालिका Taplejung Municipality 1 phunglingmun.gov.np 2 Aathrai Triveni Rural Municipality आठराई त्रिवेणी गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 aathraitribenimun.gov.np 3 Sidingwa Rural Municipality लिदिङ्वा गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 sidingbamun.gov.np 4 Faktanglung Rural Municipality फक्ताङिुङ गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 phaktanglungmun.gov.np 5 Mikhwakhola Rural Municipality लि啍वाखोिा गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 mikwakholamun.gov.np 6 Meringden Rural Municipality िेररङिेन गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 meringdenmun.gov.np 7 Maiwakhola Rural Municipality िैवाखोिा गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 maiwakholamun.gov.np 8 Yangworak Rural Municipality याङवरक गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 yangwarakmuntaplejung.gov.np 9 Sirijunga Rural Municipality लिरीजङ्घा गाउँपालिका Taplejung Rural municipality 1 sirijanghamun.gov.np 10 Fidhim Municipality दफदिि नगरपालिका Panchthar Municipality 1 phidimmun.gov.np 11 Falelung Rural Municipality फािेिुुंग गाउँपालिका Panchthar Rural municipality 1 phalelungmun.gov.np 12 Falgunanda Rural Municipality फा쥍गुनन्ि गाउँपालिका Panchthar Rural municipality 1 phalgunandamun.gov.np 13 Hilihang Rural Municipality दिलििाङ गाउँपालिका Panchthar Rural municipality 1 hilihangmun.gov.np 14 Kumyayek Rural Municipality कु म्िायक गाउँपालिका Panchthar Rural municipality 1 kummayakmun.gov.np 15 Miklajung Rural Municipality लि啍िाजुङ गाउँपालिका -

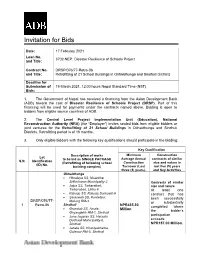

Disaster Resilience of Schools Project and Title

Invitation for Bids Date: 17 February 2021 Loan No. 3702-NEP: Disaster Resilience of Schools Project and Title: Contract No. DRSP/076/77-Retro-06 and Title: Retrofitting of 21 School Buildings in Okhaldhunga and Sindhuli Districts Deadline for Submission of 19 March 2021, 12:00 hours Nepal Standard Time (NST) Bids: 1. The Government of Nepal has received a financing from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) toward the cost of Disaster Resilience of Schools Project (DRSP). Part of this financing will be used for payments under the contracts named above. Bidding is open to bidders from eligible source countries of ADB. 2. The Central Level Project Implementation Unit (Education), National Reconstruction Authority (NRA) (the “Employer”) invites sealed bids from eligible bidders or joint ventures for the Retrofitting of 21 School Buildings in Okhaldhunga and Sindhuli Districts. Retrofitting period is of 18 months. 3. Only eligible bidders with the following key qualifications should participate in the bidding: Key Qualification Description of works Minimum Construction Lot to be bid as SINGLE PACKAGE Average Annual contracts of similar S.N. Identification (Retrofitting of following school Construction size and nature in (ID) No. building complex) Turnover (Last last five (5) years three (3) years). and Key Activities Okhaldhunga • Himalaya SS, Nisankhe, Sidhicharan Municipality-2 Contracts of similar • Jalpa SS, Tarkerabari, size and nature Tarkerabari, Likhu-8 At least one • Katunje SS, Katunje,Sunkoshi-9 contract that has • Saraswati SS, Kuntadevi, been successfully DRSP/076/77- Molung RM-3 or substantially Sindhuli 1 Retro-06 NPR435.30 completed where • Gramkali SS, Amale, Million the bidder’s Ghyanglekh RM-1, Sindhuli participation • Jana Jagaran SS, Harsahi, Dudhauli Municipality-6, exceeds: Sindhuli NPR157.00 Million. -

Climatic Variability and Land Use Change in Kamala Watershed, Sindhuli District, Nepal

climate Article Climatic Variability and Land Use Change in Kamala Watershed, Sindhuli District, Nepal Muna Neupane 1 and Subodh Dhakal 2,* 1 Central Department of Environmental Science, Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu 44600, Nepal; [email protected] 2 Department of Geology, Tri-Chandra Campus, Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu 44600, Nepal * Correspondence: [email protected] Academic Editor: Maoyi Huang Received: 21 December 2016; Accepted: 10 February 2017; Published: 18 February 2017 Abstract: This study focuses on the land use change and climatic variability assessment around Kamala watershed, Sindhuli district, Nepal. The study area covers two municipalities and eight Village Development Committees (VDCs). In this paper, land use change and the climatic variability are examined. The study was focused on analyzing the changes in land use area within the period of 1995 to 2014 and how the climatic data have evolved in different meteorological stations around the watershed. The topographic maps, Google Earth images and ArcGIS 10.1 for four successive years, 1995, 2005, 2010, and 2014 were used to prepare the land use map. The trend analysis of temperature and precipitation data was conducted using Mann Kendall trend analysis and Sen’s slope method using R (3.1.2 version) software. It was found that from 1995 to 2014, the forest area, river terrace, pond, and landslide area decreased while the cropland, settlement, and orchard area increased. The temperature and precipitation trend analysis shows variability in annual, maximum, and seasonal rainfall at different stations. The maximum and minimum temperature increased in all the respective stations, but the changes are statistically insignificant. The Sen’s slope for annual rainfall at ten different stations varied between −38.9 to 4.8 mm per year. -

Technical Assistance Layout with Instructions

Updated Initial Environmental Examination Project number: 35173-013 July 2015 NEP: Third Small Towns Water Supply and Sanitation Sector Project —Kamalamai (Sindhuli District) Prepared by ITECO Nepal (P) Ltd., SILT Consultants (P) Ltd., and Unique Engineering Consultancy (P) Ltd. for the Government of Nepal and the Asian Development Bank. This revised initial environmental examination report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Government of Nepal Ministry of Urban Development Department of Water Supply and Sewerage Small Towns Water Supply and Sanitation Sector Project (STWSSSP) Project Management Office (PMO) Panipokhari, Maharajgunj, Kathmandu, Nepal Enhance Functionality in Small Towns Water Supply and Sanitation Sector Project (STWSSSP) UPDATED INITIAL ENVIRONMENTAL EXAMINATION REPORT (IEE) for Kamalamai Small Towns Water Supply and Sanitation Sector Project Sindhuli District Kathmandu, July 2015 Submitted by: Joint Venture in Between ITECO Nepal (P) Ltd. SILT Consultants (P) Ltd. Unique Engineering P. O. Box 2147 P.O. Box 2724 Consultancy (P) Ltd. Min Bhawan, Kathmandu, Nepal Ratopul, Gaushala, Kathmandu, -

National Population and Housing Census 2011 (National Report)

Volume 01, NPHC 2011 National Population and Housing Census 2011 (National Report) Government of Nepal National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Kathmandu, Nepal November, 2012 Acknowledgement National Population and Housing Census 2011 (NPHC2011) marks hundred years in the history of population census in Nepal. Nepal has been conducting population censuses almost decennially and the census 2011 is the eleventh one. It is a great pleasure for the government of Nepal to successfully conduct the census amid political transition. The census 2011 has been historical event in many ways. It has successfully applied an ambitious questionnaire through which numerous demographic, social and economic information have been collected. Census workforce has been ever more inclusive with more than forty percent female interviewers, caste/ethnicities and backward classes being participated in the census process. Most financial resources and expertise used for the census were national. Nevertheless, important catalytic inputs were provided by UNFPA, UNWOMEN, UNDP, DANIDA, US Census Bureau etc. The census 2011 has once again proved that Nepal has capacity to undertake such a huge statistical operation with quality. The professional competency of the staff of the CBS has been remarkable. On this occasion, I would like to congratulate Central Bureau of Statistics and the CBS team led by Mr.Uttam Narayan Malla, Director General of the Bureau. On behalf of the Secretariat, I would like to thank the Steering Committee of the National Population and Housing census 2011 headed by Honorable Vice-Chair of the National Planning commission. Also, thanks are due to the Members of various technical committees, working groups and consultants. -

Section 3 Zoning

Section 3 Zoning Section 3: Zoning Table of Contents 1. OBJECTIVE .................................................................................................................................... 1 2. TRIALS AND ERRORS OF ZONING EXERCISE CONDUCTED UNDER SRCAMP ............. 1 3. FIRST ZONING EXERCISE .......................................................................................................... 1 4. THIRD ZONING EXERCISE ........................................................................................................ 9 4.1 Methods Applied for the Third Zoning .................................................................................. 11 4.2 Zoning of Agriculture Lands .................................................................................................. 12 4.3 Zoning for the Identification of Potential Production Pockets ............................................... 23 5. COMMERCIALIZATION POTENTIALS ALONG THE DIFFERENT ROUTES WITHIN THE STUDY AREA ...................................................................................................................................... 35 i The Project for the Master Plan Study on High Value Agriculture Extension and Promotion in Sindhuli Road Corridor in Nepal Data Book 1. Objective Agro-ecological condition of the study area is quite diverse and productive use of agricultural lands requires adoption of strategies compatible with their intricate topography and slope. Selection of high value commodities for promotion of agricultural commercialization -

Terms of Reference (Tor)

TERMS OF REFERENCE (TOR) Invitation for expression of interest (EOI) for partnership to implement Gender Transformative Child Protection (Girl Protect) program in Sindhuli District, Nepal. 1. Background: Plan International is an independent development and humanitarian organization that advances children’s rights and equality for girls. We believe in the power and potential of every child. But this is often suppressed by poverty, violence, exclusion and discrimination. And it is the girls who are most affected. Working together with children, young people, our supporters and partners, we strive for a just world, tackling the root causes of the challenges facing girls and all vulnerable children.We support children’s rights from birth until they reach adulthood. And we enable children to prepare for – and respond to – crises and adversity. We drive changes in practice and policy at local, national and global levels using our reach, experience and knowledge. We have been building powerful partnerships for children for 80 years, and are now active in more than 70 countries. Plan International has been working in Nepal since 1978, helping marginalized children, their families and communities to access their rights to health, hygiene and sanitation, basic education, economic security of young people, protection and safety from disasters. Through partner NGOs, community based organizations and government agencies, Plan International Nepal reaches over 42 districts. Currently, Plan International Nepal is implementing a comprehensive project in agreement with government of Nepal entitled “Child Centered Community Development Project (CCDP-Phase II)” in 14 districts of Nepal namely Banke, Bardia, Jumla Kalikot, Dolpa, Mugu, Myagdi, Parbat, Baglung, Makawanpur, Sindhuli, Rautahat, Morang, Sunsari.