Symposium Records Cd 1219

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

029I-HMVCX1924XXX-0000A0.Pdf

This Catalogue contains all Double-Sided Celebrity Records issued up to and including March 31st, 1924. The Single-Sided Celebrity Records are also included, and will be found under the records of the following artists :-CLARA Burr (all records), CARUSO and MELBA (Duet 054129), CARUSO,TETRAZZINI, AMATO, JOURNET, BADA, JACOBY (Sextet 2-054034), KUBELIK, one record only (3-7966), and TETRAZZINI, one record only (2-033027). International Celebrity Artists ALDA CORSI, A. P. GALLI-CURCI KURZ RUMFORD AMATO CORTOT GALVANY LUNN SAMMARCO ANSSEAU CULP GARRISON MARSH SCHIPA BAKLANOFF DALMORES GIGLI MARTINELLI SCHUMANN-HEINK BARTOLOMASI DE GOGORZA GILLY MCCORMACK Scorn BATTISTINI DE LUCA GLUCK MELBA SEMBRICH BONINSEGNA DE' MURO HEIFETZ MOSCISCA SMIRN6FF BORI DESTINN HEMPEL PADEREWSKI TAMAGNO BRASLAU DRAGONI HISLOP PAOLI TETRAZZINI BI1TT EAMES HOMER PARETO THIBAUD CALVE EDVINA HUGUET PATTt WERRENRATH CARUSO ELMAN JADLOWKER PLANCON WHITEHILL CASAZZA FARRAR JERITZA POLI-RANDACIO WILLIAMS CHALIAPINE FLETA JOHNSON POWELL ZANELLIi CHEMET FLONZALEY JOURNET RACHM.4NINOFF ZIMBALIST CICADA QUARTET KNIIPFER REIMERSROSINGRUFFO CLEMENT FRANZ KREISLER CORSI, E. GADSKI KUBELIK PRICES DOUBLE-SIDED RECORDS. LabelRed Price6!-867'-10-11.,613,616/- (D.A.) 10-inch - - Red (D.B.) 12-inch - - Buff (D.J.) 10-inch - - Buff (D.K.) 12-inch - - Pale Green (D.M.) 12-inch Pale Blue (D.O.) 12-inch White (D.Q.) 12-inch - SINGLE-SIDED RECORDS included in this Catalogue. Red Label 10-inch - - 5'676 12-inch - - Pale Green 12-inch - 10612,615j'- Dark Blue (C. Butt) 12-inch White (Sextet) 12-inch - ALDA, FRANCES, Soprano (Ahl'-dah) New Zealand. She Madame Frances Aida was born at Christchurch, was trained under Opera Comique Paris, Since Marcltesi, and made her debut at the in 1904. -

VOCAL 78 Rpm Discs Minimum Bid As Indicated Per Item

VOCAL 78 rpm Discs Minimum bid as indicated per item. Listings “Just about 1-2” should be considered as mint and “Cons. 2” with just the slightest marks. For collectors searching top copies, you’ve come to the right place! The further we get from the time of production (in many cases now 100 years or more), the more difficult it is to find such excellent extant pressings. Some are actually from mint dealer stocks and others the result of having improved copies via dozens of collections purchased over the past fifty years. * * * For those looking for the best sound via modern reproduction, those items marked “late” are usually of high quality shellac, pressed in the 1950-55 period. A number of items in this particular catalogue are excellent pressings from that era. * * * Please keep in mind that the minimum bids are in U.S. Dollars, a benefit to most collectors. * * * “Text label on verso.” For a brief period (1912-14), Victor pressed silver-on-black labels on the reverse sides of some of their single-faced recordings, usually with a translation of the text or similarly related comments. BESSIE ABOTT [s]. Riverdale, NY, 1878-New York, 1919. Following the death of her father which left her family penniless, Bessie and her sister Jessie (born Pickens) formed a vaudeville sister vocal act, accompanying themselves on banjo and guitar. Upon the recommendation of Jean de Reszke, who heard them by chance, Bessie began operatic training with Frida Ashforth. She subsequently studied with de Reszke him- self and appeared with him at the Paris Opéra, making her debut as Gounod’s Juliette. -

Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-15-2018 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Bourne, Thaddaeus, "Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1779. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1779 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus James Bourne, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 This study will examine the Zwischenfach colloquially referred to as the baritenor. A large body of published research exists regarding the physiology of breathing, the acoustics of singing, and solutions for specific vocal faults. There is similarly a growing body of research into the system of voice classification and repertoire assignment. This paper shall reexamine this research in light of baritenor voices. After establishing the general parameters of healthy vocal technique through appoggio, the various tenor, baritone, and bass Fächer will be studied to establish norms of vocal criteria such as range, timbre, tessitura, and registration for each Fach. The study of these Fächer includes examinations of the historical singers for whom the repertoire was created and how those roles are cast by opera companies in modern times. The specific examination of baritenors follows the same format by examining current and -

![[T] IMRE PALLÓ](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5305/t-imre-pall%C3%B3-725305.webp)

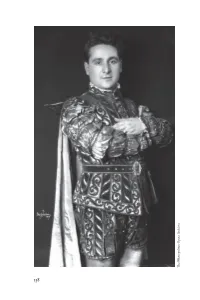

[T] IMRE PALLÓ

VOCAL 78 rpm Discs FRANZ (FRANTISEK) PÁCAL [t]. Leitomischi, Austria, 1865-Nepomuk, Czechoslo- vakia, 1938. First an orchestral violinist, Pácal then studied voice with Gustav Walter in Vienna and sang as a chorister in Cologne, Bremen and Graz. In 1895 he became a member of the Vienna Hofoper and had a great success there in 1897 singing the small role of the Fisherman in Rossini’s William Tell. He then was promoted to leading roles and remained in Vienna through 1905. Unfor- tunately he and the Opera’s director, Gustav Mahler, didn’t get along, despite Pacal having instructed his son to kiss Mahler’s hand in public (behavior Mahler considered obsequious). Pacal stated that Mahler ruined his career, calling him “talentless” and “humiliating me in front of all the Opera personnel.” We don’t know what happened to invoke Mahler’s wrath but we do know that Pácal sent Mahler a letter in 1906, unsuccessfully begging for another chance. Leaving Vienna, Pácal then sang with the Prague National Opera, in Riga and finally in Posen. His rare records demonstate a fine voice with considerable ring in the upper register. -Internet sources 1858. 10” Blk. Wien G&T 43832 [891x-Do-2z]. FRÜHLINGSZEIT (Becker). Very tiny rim chip blank side only. Very fine copy, just about 2. $60.00. GIUSEPPE PACINI [b]. Firenze, 1862-1910. His debut was in Firenze, 1887, in Verdi’s I due Foscari. In 1895 he appeared at La Scala in the premieres of Mascagni’s Guglielmo Ratcliff and Silvano. Other engagements at La Scala followed, as well as at the Rome Costanzi, 1903 (with Caruso in Aida) and other prominent Italian houses. -

La Traviata GIUSEPPE VERDI Temporada 2020-2021

La traviata GIUSEPPE VERDI Temporada 2020-2021 Temporada Con la colaboración de: 1 La traviata - Giuseppe Verdi Patronato de la Fundación del Gran Teatre del Liceu Comisión ejecutiva de la Fundación del Gran Teatre del Liceu Presidente de honor Presidente President de la Generalitat de Catalunya Salvador Alemany Mas Presidente del patronato Vocales representantes de la Generalitat de Catalunya Salvador Alemany Mas Àngels Ponsa Roca, Lluís Baulenas Cases Vicepresidenta primera Vocales representantes del Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte Àngels Ponsa Roca Amaya de Miguel Toral, Antonio Garde Herce Vicepresidente segundo Vocales representantes del Ayuntamiento de Barcelona Andrea Gavela Llopis Joan Subirats Humet, Marta Clarí Padrós Vicepresidente tercero Vocal representant de la Diputació de Barcelona Joan Subirats Humet Joan Carles Garcia Cañizares Vicepresidenta cuarta Vocales representantes de la Societat del Gran Teatre del Liceu Núria Marín Martínez Javier Coll Olalla, Manuel Busquet Arrufat Vocales representantes de la Generalitat de Catalunya Vocales representantes del Consejo de Mecenazgo Lluis Baulenas Cases, Irene Rigau Oliver, Angels Barbara Fondevila Luis Herrero Borque, Elisa Durán Montolío Vocales representantes del Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte Secretario Javier García Fernández, Amaya de Miguel Toral, Joan Francesc Joaquim Badia Armengol Marco Conchillo, Santiago de Torres Sanahuja Director general Vocales representantes del Ayuntamiento de Barcelona Valentí Oviedo Cornejo Marta Clari Padrós, Josep Maria Vallès Casadevall -

Here Is a PDF File of the First 14 Pp. from a Chapter

The Metropolitan Opera Archives The Metropolitan 158 lauri-volpi vs. the verismo style FC: Old-style heroic tenors such as Giacomo Lauri-Volpi sang the center and bottom notes lightly and sweetly but let loose on top. Lauri-Volpi’s repertory was vast, but the operas that suited him best were Tell, Puritani, Poliuto, Turandot,a Luisa Miller and Ugonotti, heroic works where he could neglect the center notes and seek to display brilliance and high notes and where he could emphasize classical style and purity of tone over passion. In contrast verismo singers favor the center notes and sing with portamento and heart. In verismo the theatrical effect of the phrase is more important than purity of tone. Words sometimes are more important than music, and you have to use the center notes to interpret them. SZ: What are the characteristics of the verismo tenor? FC: The verismo tenor has a round, strong middle voice and push- es high notes with his guts. Caruso gave us this manner of singing. As a verismo tenor you do try to sing beautifully, lightly and sweet- ly, at moments. You must have this chiaroscuro, this contrast. But a In common with Iris Adami Corradetti, Gina Cigna, Magda Olivero, Rosa Raisa and Eva Turner Corelli always pronounced the name “Turando.” Opposite: Giacomo Lauri-Volpi as il Duca, Met, 1923. He called Rigoletto “the opera that made my fortune.” He made his Scala and Met debuts in it and sang it more than 300 times. 159 you can’t sing some notes in falsettoneb—no more of that!—you’ve got to sing with your real voice even when you sing softly. -

To Mid-Twentieth Century

Acquiring, Preserving, and Exhibiting a Comprehensive Collection of Vocal Music Recordings from the Early- to Mid-Twentieth Century by Janneka Guise, Bryan Martin, James Mason, and Rebecca Shaw Abstract The Stratton-Clarke collection consists of approximately 200 linear feet of 78 and 33 1/3 rpm records, and thousands of digitized recordings that represents a comprehensive history of early twentieth century recorded Western sound, specifically opera -- its artists, roles, and early legacy from 78 rpm to early long play records. Along with some ephemera and several pieces of historic playback equipment, a large financial gift will offset the costs of processing, preserving and providing access to the various formats represented in the collection. As the largest music research collection in Canada, the University of Toronto Music Library is fortunate to have the capacity to manage a donation of this magnitude. Each of our four authors has an important role to play to make the project a success. In this article we present a history and background of John Stratton, Stephen Clarke, and the collection itself, and document the many facets of a library taking on a donation of this size: donor relations and collaboration with the University’s advancement team and other stakeholders; the project management involved in making space and designing workflow for cataloguing, processing, and storage; archival description of the 78s and ephemera; preservation of the digital objects and digitization strategies for the analog recordings; the challenges and opportunities of working with large financial gifts; teamwork and managing students; and future plans for physical and online exhibitions of the collection. -

Bel Paese Di Libertini

[TsegretTSTDonCTov^nr La scena Bel Paese di libertini Dal ventiduenne pesarese Luigi Bassi, il primo, intervista di Paola Rizzi con all'insuperato cantante/dongiovanni italoamericano Rodolfo Celletti Ezio Pinza, a Ruggero Raimondi, che lo ha Rodolfo Celletti critico e musicologo interpretato nel film di Losey, sono state soprattutto forse il maggior esperto italiano nei prò blemi della vocalità Ha scritto fra 1 altro voci italiane a portare Don Giovanni nel mondo. // (eafro d opera in disco c » ^^ e si sfoglia il catalogo delle rap ta ad avere successo, proprio per 11 modo molto intelligente e mancava di drammaticità il Don Giovanni di Salisburgo E anche un gran ^^ presentazioni del Don Giovanni particolare In cui Mozart trattava 11 canto Tamburini ha portato il suo Don Giovanni dap de rossiniano Ha una voce perfetta canta be m"^m nell arco di cent anni dalla prima In effetti in «Don Giovanni non e e grande pertutto soprattutto a Parigi e a Londra che nissimo ma gli manca il pepe e freddo ci si Imbatte in cifre Impressionanti messo in spazio per il virtuosismo vocale salvo quaico allora dettavano la moda in particolare il Cosa ne penta del due Don Giovanni che si scena a Praga cinquecenlotrentadue volte a sa per Donna Anna e Donna Elvira e in Italia Theatre Italien alterneranno alla Scala, Thomas Alien e Vienna quattrocentosetlantadue quattrocen sia i cantanti che il pubblico a quel tempo È andato anche In Germania? José Van Dam? preferivano opere in cui I interprete potesse tonovantuno a Berlino trecento a Londra una No li e era una -

Cronologia Dels 175 Anys Del Liceu

anys del Liceu Junts seguirem fent història Cronologia dels 175 anys del Liceu 1837 Constitució de la Sociedad Dramática de Aficionados (24 febrer), a l’antic convent de Montsió i destinada al conreu de les arts. Es considera el nucli institucional del futur Liceu. El 14 de novembre s’aprova el primer reglament del Liceo Filodramático de Montesión, una societat per al desenvolupament de l’art dramàtic i el musical, l’origen del Conservatori del Liceu. Primera representació al convent de Montsió: El marido de mi mujer de Ventura de la Vega (21 agost). 1838 Primera representació d’una òpera al Convent de Montsió: Norma de Bellini (3 febrer). Reial Decret on s’autoritza el canvi de nom pel de Liceo Filarmónico Dramático Barcelonés de S. M. La Reina Isabel II (25 juny), amb la finalitat de promoure l’ensenyament teatral i musical i la de dur a terme representacions escèniques de teatre i òpera. 1841 Primeres documentacions per a la recerca d’un nou espai per a les activitats del Liceu. 1844 Adquisició i enderrocament de l’antic convent de Trinitaris (9 juny) a la Rambla, cantonada del carrer de Sant Pau. Oferta d’accions del futur teatre i aprovació del reglament (25 juliol), configurant la propietat privada del Liceu. anys del Liceu Junts seguirem fent història 1845 S’inicien les obres del Gran Teatre del Liceu (11 abril), per Miquel Garriga i Roca i Josep Oriol Mestres. El model fou l’arquitectura del Teatro allà Scala de Milà. 1847 Inauguració del Gran Teatre del Liceu (4 abril) que durant molts anys serà considerat el teatre d’òpera amb més capacitat d’Europa (més de tres mil persones). -

VOCAL 78 Rpm Discs Minimum Bid As Indicated Per Item

VOCAL 78 rpm Discs Minimum bid as indicated per item. Listings “Just about 1-2” should be considered as mint and “Cons. 2” with just slight marks. For collectors searching top copies, you’ve come to the right place! The further we get from the era of production (in many cases now 100 years or more), the more difficult it is to find such excellent extant pressings. Some are actually from mint dealer stocks and others the result of having improved copies via dozens of collections purchased over the past fifty years. * * * For those looking for the best sound via modern reproduction, those items marked “late” are usually of high quality shellac, pressed in the 1950-55 period. A number of items in this particular catalogue are excellent pressings from that era. Also featured are many “Z” shellac Victors, their best quality surface material (later 1930s) and PW (Pre-War) Victor, almost as good surface material as “Z”. Likewise laminated Columbia pressings (1923- 1940) offer particularly fine sound. * * * Please keep in mind that the minimum bids are in U.S. Dollars, a benefit to most collectors. * * * “Text label on verso.” For a brief period (1912-‘14), Victor pressed silver-on-black labels on the reverse sides of some of their single-faced recordings, usually featuring translations of the text or similarly related comments. VERTICALLY CUT RECORDS. There were basically two systems, the “needle-cut” method employed by Edison, which was also used by Aeolian-Vocalion and Lyric and the “sapphire ball” system of Pathé, also used by Rex. and vertical Okeh. -

La Favorite (2017-2018).Pdf

TEMPORADA 2017-2018 TOURBILLON EXTRA-PLAT 5377 HISTORY IS STILL BEING WRITTEN... LA FAVORITE NAPOLÉON BONAPARTE (1769-1821) GAETANO DONIZETTI CLIENTE CÉLEBRE DE BREGUET – WWW.BREGUET.COM NAP_5377-Favorite_150x210.indd 1 21.09.17 11:04 Gracias por transmitirnos Hay un lugar para los vuestra energía durante que saben divertirse. estos 20 años. Si quieres emocionarte con los mejores eventos culturales, conocer a los personajes que admiras y experimentar con el arte en familia... Este es tu sitio. Solo pasa aquí, movistarlikes.es Movistar Likes Te gusta. Te apuntas. Lo vives. Foto: Magali Dougados Fotógrafo: Javier del Real endesa.com Página_15x21+3_S&S_Endesa2017_BAILARINA_TR_P_M_ES_v6.indd 1 17/10/17 17:03 MÁS DE HOY MÁS DE TODOS MÁS TEATRO REAL 1 PATROCINADORES DEL BICENTENARIO MECENAS PRINCIPAL MECENAS ENERGÉTICO TEMPORADA 2017-2018 PATROCINADORES DEL BICENTENARIO LA FAVORITE GAETANO DONIZETTI (1797-1848) Ópera en cuatro actos Libreto de Alphonse Royer, Gustave Vaëz y Eugène Scribe Estrenada en la Opéra de Paris el 2 de diciembre de 1840 Estrenada en el Teatro Real el 19 de noviembre de 1850 GALA CONMEMORATIVA de la reapertura del Teatro Real el 11 de octubre de 1997 Ópera en versión de concierto 2, 6 de noviembre ADMINISTRACIONES PÚBLICAS ADMINISTRACIÓN PÚBLICA FUNDADORAS COLABORADORA 3 «Maldigo esta alianza, maldigo la indigna ofensa que sobre mí vuestra locura ha lanzado junto con el oro. ¡Rey! Guardemos, vos, el poder; yo, el honor, mi único tesoro.» FERNAND. LA FAVORITE (ACTO III, ESCENA XII) ALPHONSE ROYER, GUSTAVE VAËZ Y EUGÈNE -

![C C (Composition from Deux Poemes De Louis Aragon [Dö Paw-Emm Duh Lôô-Ee Ah-Rah-Gaw6] — Two Poems by Louis Aragon — Set T](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8896/c-c-composition-from-deux-poemes-de-louis-aragon-d%C3%B6-paw-emm-duh-l%C3%B4%C3%B4-ee-ah-rah-gaw6-two-poems-by-louis-aragon-set-t-4348896.webp)

C C (Composition from Deux Poemes De Louis Aragon [Dö Paw-Emm Duh Lôô-Ee Ah-Rah-Gaw6] — Two Poems by Louis Aragon — Set T

C C (composition from Deux poemes de Louis Aragon [dö paw-emm duh lôô-ee ah-rah-gaw6] — Two Poems by Louis Aragon — set to music by Francis Poulenc [frah6-seess pôô-lah6k]) C dur C C Dur C TSAY DOOR C (key of C major, German designation) C moll C c Moll C TSAY MAWL C (key of c minor, German designation) Ca the yowes C Ca’ the Yowes C KAH (the) YOHZ C (poem by Robert Burns [RAH-burt BURNZ] set to music by Ralph Vaughan Williams [RALF VAWN WILL-lihummz]) C (In Britain, Ralph may be pronounced RAYF) Caamano C Roberto Caamaño C ro-VEHR-toh kah-MAH-n’yo Caba C Eduardo Caba C ay-dooAR-doh KAH-vah Cabaletta C {kah-bah-LETT-tah} kah-bah-LAYT-tah Caballe C Montserrat Caballé C mawnt-sehr-RAHT kah-vah-l’YAY Caballero C Manuel Fernández Caballero C mah-nooELL fehr-NAHN-dehth kah-vah-l’YAY- ro Cabanilles C Juan Bautista José Cabanilles C hooAHN bahoo-TEESS-tah ho-SAY kah-vah- NEE-l’yayss Cabecon C Antonio de Cabeçon C ahn-TOH-neeo day kah-vay-SAWN C known also as Antonio de Cabezon [kah-vay-THAWN]) Cabello mas sutil C Del cabello más sutil C dell kah-VELL-l’yo MAHSS soo-TEEL C (Of That Softest Hair) C (song by Fernando J. Obradors [fehr-NAHN-doh (J.) o-VRAH-thawrss]) Cabezon C Antonio de Cabezón C ahn-TOH-neeo day kah-vay-THAWN C (known also as Antonio de Cabeçon [ahn-TOH-neeo day kah-vay-SAWN]) Cabrito C Un cabrito C oon kah-VREE-toh C (a medieval song of the Passover sung by the Jews who were expelled from Spain in 1492 and who settled in Morocco) Caccia C La caccia C lah KAH-chah C (The Hunt) C (allegro [ahl-LAY-gro] number in L’autunno [lahoo-TOON-no]