2016 Designing Chessmen Brochure3.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Es Probable, De Hecho, Que La Invencible Tristeza En La Que Se

Surrealismo y saberes mágicos en la obra de Remedios Varo María José González Madrid Aquesta tesi doctoral està subjecta a la llicència Reconeixement- NoComercial – CompartirIgual 3.0. Espanya de Creative Commons. Esta tesis doctoral está sujeta a la licencia Reconocimiento - NoComercial – CompartirIgual 3.0. España de Creative Commons. This doctoral thesis is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 3.0. Spain License. 2 María José González Madrid SURREALISMO Y SABERES MÁGICOS EN LA OBRA DE REMEDIOS VARO Tesis doctoral Universitat de Barcelona Departament d’Història de l’Art Programa de doctorado Història de l’Art (Història i Teoria de les Arts) Septiembre 2013 Codirección: Dr. Martí Peran Rafart y Dra. Rosa Rius Gatell Tutoría: Dr. José Enrique Monterde Lozoya 3 4 A María, mi madre A Teodoro, mi padre 5 6 Solo se goza consciente y puramente de aquello que se ha obtenido por los caminos transversales de la magia. Giorgio Agamben, «Magia y felicidad» Solo la contemplación, mirar una imagen y participar de su hechizo, de lo revelado por su magia invisible, me ha sido suficiente. María Zambrano, Algunos lugares de la pintura 7 8 ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN 13 A. LUGARES DEL SURREALISMO Y «LO MÁGICO» 27 PRELUDIO. Arte moderno, ocultismo, espiritismo 27 I. PARÍS. La «ocultación del surrealismo»: surrealismo, magia 37 y ocultismo El surrealismo y la fascinación por lo oculto: una relación polémica 37 Remedios Varo entre los surrealistas 50 «El giro ocultista sobre todo»: Prácticas surrealistas, magia, 59 videncia y ocultismo 1. «El mundo del sueño y el mundo real no hacen más que 60 uno» 2. -

Oral History Interview with Enrico Donati

Oral history interview with Enrico Donati Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... Oral history interview with Enrico Donati AAA.donaenri Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: Oral history interview with Enrico Donati Identifier: AAA.donaenri Date: 1997 Jan. 7 Creator: Donati, Enrico, 1909-2008 (Interviewee) Temkin, Ann (Interviewer) Extent: 95 Pages (Transcript) Language: English . Administrative Information Acquisition Information Donated 2000 by Ann Temkin. Location of Originals Location of original sound recording unknown. Reproduction Note Item is a transcript. Restrictions Use of original papers requires an appointment and is limited -

Dorothea Tanning

DOROTHEA TANNING Born 1910 in Galesburg, Illinois, US Died 2012 in New York, US SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2022 ‘Dorothea Tanning: Printmaker’, Farleys House & Gallery, Muddles Green, UK (forthcoming) 2020 ‘Dorothea Tanning: Worlds in Collision’, Alison Jacques Gallery, London, UK 2019 Tate Modern, London, UK ‘Collection Close-Up: The Graphic Work of Dorothea Tanning’, The Menil Collection, Houston, Texas, US 2018 ‘Behind the Door, Another Invisible Door’, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, Spain 2017 ‘Dorothea Tanning: Night Shadows’, Alison Jacques Gallery, London, UK 2016 ‘Dorothea Tanning: Flower Paintings’, Alison Jacques Gallery, London, UK 2015 ‘Dorothea Tanning: Murmurs’, Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York, US 2014 ‘Dorothea Tanning: Web of Dreams’, Alison Jacques Gallery, London, UK 2013 ‘Dorothea Tanning: Run: Multiples – The Printed Oeuvre’, Gallery of Surrealism, New York, US ‘Unknown But Knowable States’, Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco, California, US ‘Chitra Ganesh and Dorothea Tanning’, Gallery Wendi Norris at The Armory Show, New York, US 2012 ‘Dorothea Tanning: Collages’, Alison Jacques Gallery, London, UK 2010 ‘Dorothea Tanning: Early Designs for the Stage’, The Drawing Center, New York, US ‘Happy Birthday, Dorothea Tanning!’, Maison Waldberg, Seillans, France ‘Zwischen dem Inneren Auge und der Anderen Seite der Tür: Dorothea Tanning Graphiken’, Max Ernst Museum Brühl des LVR, Brühl, Germany ‘Dorothea Tanning: 100 years – A Tribute’, Galerie Bel’Art, Stockholm, Sweden 2009 ‘Dorothea Tanning: Beyond the Esplanade -

JULIEN LEVY. ARTIST and ART DEALER. SHARED EXPERIENCE 327 Physical Work and Expressed Great Admiration for Hebdomeros, the Artist’S Only Published Novel at the Time

326 GIORGIO DE CHIRICO – JULIEN LEVY ARTIST AND ART DEALER. SHARED EXPERIENCE Katherine Robinson One afternoon in the late autumn of 1930, while Julien Levy was busy planning the imminent opening of his gallery, he looked up from his work and saw a disparate collection of rulers and com- passes hanging on the wall in front of him. These technical instruments, with which he was execut- ing the gallery’s architectural design, were casually positioned above a table upon which the remain- der of a snack had been left: a couple of cookies and some wrapping papers. By means of this appar- ently accidental arrangement, Levy realized in a flash of intuition that a Metaphysical Interior by Giorgio de Chirico was in the process of inaugurating the gallery, well before the official opening. The aspiring art dealer considered the event a portent of good fortune and it is on this note that he began to tell the story of his gallery in Memoir of an Art Gallery.1 In the city that was to become the next capital of modern art after Paris, Julien Levy was debut- ing as an art dealer at twenty-four years of age.2 When Giorgio de Chirico crossed the Atlantic at the end of the summer of 1936 to prepare his solo exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery at 602 Madison Avenue, he had just turned forty-eight. In his pioneering endeavour to introduce the contemporary art of Europe to the American public, the young art dealer was guided by an inherent gift of sensitivi- ty and intuitive discernment, not only for the art forms of his time but specifically concerning his rela- tionship to individual artists.3 A special rapport was to develop between Giorgio de Chirico and Julien Levy; although not necessarily intimate, it was one of trust and reciprocal esteem, qualities that are perceived in the written memoirs of both these protagonists.4 Levy considered de Chirico to be one of the principal founders of 20th century art.5 He recognized the pioneering value of his early meta- 1 J. -

Chess-Moves-November

November / December 2006 NEWSLETTER OF THE ENGLISH CHESS FEDERATION £1.50 European Union Individual Chess Championships Liverpool World Museum Wednesday 6th September to Friday 15th September 2006 FM Steve Giddins reports on round 10 Nigel Short became the outright winner of the 2006 EU Championship, by beating Mark Hebden in the 10th round, whilst his main rivals could only draw. The former world title challenger later declared himself “extremely chuffed” at having won on his first appearance in an international tournament in his home country, since 1989. Hebden is a player whose opening repertoire is well-known, and has been almost constant for his entire chess-playing life. As Black against 1 e4, he plays only 1...e5, usually either the Marshall or a main line Chigorin. Short avoided these with 3 Bc4, secure in the knowledge that Hebden only ever plays 3...Nf6. Over recent years, just about every top-level player has abandoned the Two Knights Defence, on the basis that Black does not have enough compensation after 4 Ng5. Indeed, after the game, Short commented that “The Two Knights just loses a pawn!”, and he added that anybody who played the line regularly as Black “is taking their life in their hands”. Hebden fought well, but never really had enough for his pawn, and eventually lost the ending. Meanwhile, McShane and Sulskis both fought out hard draws with Gordon and Jones respectively. Unlike Short, McShane chose to avoid a theoretical dispute and chose the Trompowsky. He did not achieve much for a long time, and although a significant outb of manoeuvring eventually netted him an extra pawn in the N+P ending, Black’s king was very active and he held the balance. -

Computer Vision System for a Chess-Playing Robot

University of Sheffield Computer Vision System for a Chess-Playing Robot Gregory Ives Supervisor: Jon Barker This report is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of MComp Computer Science in the Department of Computer Science May 1, 2019 Declaration All sentences or passages quoted in this report from other people’s work have been specifically acknowledged by clear cross-referencing to author, work and page(s). Any illustrations that are not the work of the author of this report have been used with the explicit permission of the originator and are specifically acknowledged. I understand that failure to do this amounts to plagiarism and will be considered grounds for failure in this project and the degree examination as a whole. Signed: Gregory Ives Date: May 1, 2019 ii Abstract Computer vision is the field of computer science which attempts to gain an understanding of the content within a digital image or video. Since its conception in the late 1960s, it has been used for a huge range of applications, from agriculture to autonomous vehicles. The aim of this project is to design a computer vision system to be used by a chess-playing robot, capable of detecting opponents’ moves and returning the best move to be played by the robot. The system should be robust to changes in perspective, lighting and other environmental factors so that it can be used in any reasonable setting. This report researches existing computer vision systems for chess, comparing the methods they use and the constraints placed on them. New techniques are then explored, with the aim of creating a system which performs well under minimal constraints. -

Wolfgang Paalen

Wolfgang Paalen Implicit Spaces May 17 – July 12, 2007 “The main concern is not to operate for eternity, but in eternity.” from Wolfgang Paalen´s scrapbook Voyage nord-ouest, Canada/Alaska 1939 Cover Image Wolfgang Paalen, Ciel de pieuvre (Octopus sky) Fumage and oil on canvas 1938 97 x 130 cm (38 1/4 x 51 1/4 in.) More than half a century ago Wolfgang Paalen in the Bay Area Paalen worked and exhibited for some years together with his wife, Luchita, and their friends Gordon Onslow Ford, Jacqueline Johnson and Lee Mullican in Mill Valley. It was here in 1949 that he published his essay with the strange title Dynaton, in which he contemplated space and time, our changing image of the cosmos caused by the new physics, and what it meant for an artist to draw from a universe of the imaginable and no longer merely from the three known dimensions of the visible world. Jacqueline Johnson later wrote, “Paalen´s voice held the flashing presence of mystery where, as in childhood, it is central to all the threads of reality, of an identity to come, the clue of the concealed.” In this way, Dynaton was formed as a small artists’ group. Onslow Ford consequently called him “the man of many possibilities.” For Lee he embodied, “the advent of the Lord of Prismatic Situations.” Jacqueline adored him as a, “man with a spark of nuclear presence.” And Luchita, his wife, called him “the most intriguing spirit possible, but the most impossible man to live with.” Each friend acknowledged his visionary genius. -

American Chess Federation Congress at Boston the U. S. S. R

, , • • • • ,. • • • 1I0NOR PRIZE PROBLEM E. ZEP!....ER , • • Chelmlford, England I , • • , , • • WHITE MAl1ES IN FIVE MOVES -"----- - --.. - - - • THE OFFICIAL ORGAN OF THE AMERICAN CHESS FEDERA nON This Issue Features A Generous Selection of Games from the . American Chess Federation Congress at Boston The U. s. s. R. Chalnpionship . .• f ' and Other Tourneys • • _.-_.- - - --~--- AUGUST, 1938 M"ONTHLY- - 30. cu.. ANNUALLY $3.00 7he BY THE WAY THE A. C. F. CONGRESS This year· s c·ongress at Boston (treated in detail in another part of this issue) was a great success in many ways. The steady growth of interest in chess was mirrored in the numerous summaries and articles in the Boston. press by REVIEW John F. Barry, Charles Sumner Jacobs and Frank OFFICI!.L ORGAN OF THE Perkins. AMIiRICI,N CHESS FEDERATION The coverage by the New York Tim(!J was n.ot l!P to its high level, but chess players were Editors: grateful for its large and splendid selection. ISRAEL .A. HOROWITZ of some of the best games. SAMUEL S. COHEN An unfortun.ate aftermath of the tourney was the accideot which occurred to Mrs. Bain, Mrs. AJSoriate Editors: McCready and Miss W eart. 11l1ey were return. FRED REINFELO ing from Boston during the rainy .~peIl, and BARNIE F. WINKELMAN their car skidded on a slippery pavement, going into a telegraph pole. The car overturned, pin_ Problem Editor: ning Miss Weart, who luckily escaped with a R. CHENEY fractured shoulder. Mrs. Bain suffered a frac. tured vertebra, necessitating the wearing of a cast for several months. We do not know the Vol. -

Press Release Dalí. All of the Poetic Suggestions and All of the Plastic

Dalí. All of the poetic suggestions and all of the plastic possibilities DATES: April 27 – September 2, 2013 PLACE: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (Madrid) Sabatini Building. 3rd floor. ORGANIZED BY: Museo Reina Sofía and Centre Pompidou, Paris, in collaboration with the Salvador Dalí Museum Saint Petersburg (Florida). With the special collaboration of the Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Figueres. CHIEF CURATOR: Jean-Hubert Martin CURATORS: Montse Aguer (exhibition at the Museo Reina Sofía, Madrid), Jean-Michel Bouhours and Thierry Dufrêne COORDINATOR: Aurora Rabanal The Museo Reina Sofía presents a major exhibition dedicated to Salvador Dalí, one of the most comprehensive shows yet held on the artist from Ampurdán. Gathered together on this unique occasion are more than 200 works from leading institutions, private collections, and the three principal repositories of Salvador Dalí’s work, the Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí (Figueres), the Salvador Dalí Museum of St. Petersburg (Florida), and the Museo Reina Sofía (Madrid), which in this way are joining forces to show the public the best of their collections. The exhibition, a great success with the public when shown recently at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, aims to revalue Dalí as a thinker, writer and creator of a peculiar vision of the world. One exceptional feature is the presence of loans from leading institutions like the MoMA (New York), which is making available the significant work The Persistence of Memory (1931); the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which is lending Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War) (1936); the Tate Modern, whose contribution is Metamorphosis of Narcissus (1937); and the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts, Belgium, the lender of The Temptation of St Anthony (1946). -

Like the Traditional Mexican Dresses She Usually Wore and Posed In, Her Distinctive Attire Can Be Considered in Symbolic Terms

FriDa Kahlo (Mexican, 1907–1954) / annE umLanD like the traditional Mexican dresses she usually wore and posed in, her distinctive attire can be considered in costume. Yet her dangling earring, delicately boned hands and face, and diminutive high- symbolic terms as a form of self-defining costume. heeled shoes—along with the numerous tendrils of cutoff hair that carpet the floor— send signals that conflict with those of the “The picture is certainly one of Frida’s best, aside from Barr’s overly saccharine close-cropped haircut and man’s suit. Like as well as an exceptional document,” wrote translation of the Spanish lyrics Kahlo had man ray’s photographs of Kahlo’s friend Lieutenant Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., to alfred H. carefully painted across the top of her canvas, and loyal supporter marcel Duchamp in the Barr, Jr., director of The museum of modern his exchange with Kaufmann is revealing.4 guise of his female alter ego rrose Sélavy, art, referring to Frida Kahlo’s Autorretrato it testifies to the early priority he placed on the painting presents us with an image of con pelo cortado (Self-Portrait with Cropped acquiring a work by Kahlo as an important someone posing, not attempting to pass, as Hair) (1940, no. 1).1 Kaufmann and Barr had representative of contemporary mexican art the opposite sex.8 The deliberate ambivalence spent part of the summer of 1942 traveling and to the strong impression Kahlo’s and resultant gender confusion contribute together in mexico, looking for works of art Autorretrato con pelo cortado had made on to the work’s uncanny allure. -

Still SELF-UPDATING

GE THE ORIGINS OF SYNTHETIC TIMBRE SERIALISM AND THE PARISIAN CONFLUENCE, 1949–52 by John-Philipp Gather October 2003 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of State University of New York at Buffalo in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music COPYRIGHT NOTE The first fifty copies were published by the author. Berlin: John-Philipp Gather, 2003. Printed by Blasko Copy, Hilden, Germany. On-demand copies are available from UMI Dissertation Services, U.S.A. Copyright by John-Philipp Gather 2003 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many persons have contributed to the present work. I would like to name first and foremost my major advisor Christopher Howard Gibbs for his unfailing support and trust throughout the five-year writing period, guiding and accompanying me on my pathways from the initial project to the present study. At the State University of New York at Buffalo, my gratitude goes to Michael Burke, Carole June Bradley, Jim Coover, John Clough, David Randall Fuller, Martha Hyde, Cort Lippe, and Jeffrey Stadelman. Among former graduate music student colleagues, I would like to express my deep appreciation for the help from Laurie Ousley, Barry Moon, Erik Oña, Michael Rozendal, and Matthew Sheehy. A special thanks to Eliav Brand for the many discussion and the new ideas we shared. At the Philips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire, I am grateful to Jacquelyn Thomas, Peter Schulz, and Rohan Smith, who helped this project through a critical juncture. I also extend my warm thanks to Karlheinz Stockhausen, who composed the music at the center of my musicological research. -

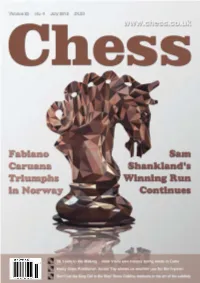

Chess-July.Pdf

Edinburgh Expedition Ever a man for a challenge, Sean Marsh returned to Edinburgh for a long weekend to put some of Chess in Schools and Communities’ plans into action It is strange how plans can snowball. Edinburgh was not originally in the thoughts of Chess in Schools and Communities (‘CSC’), when expansion plans were discussed. In fact, the closest we came in the discussions was Newcastle and I delivered a CSC training day there in April 2017. Richard Payne, Chairperson of Lothian Junior Chess, attended the Newcastle day and shortly afterwards he contacted me to suggest the innovative plan of adding a training day to his junior chess tournament, with the hope of attracting any parents and teachers who happened to be at the tournament with their juniors at the time. The tournament in question was in Edinburgh and I delivered the training day there in October 2017. It was a success and it generated a lot of interest. CSC provided some of our new contacts with boards and sets, and I have maintained regular contact with several of the people who attended the courses. Colin Paterson, who is currently helping me with more expansion plans, even made the long trip to the London Chess Classic specifically for one of my full length training days, and Andrew MacQueen joined me on Teesside for a number of shadowing sessions in the Spring term. Meanwhile, we also made more schools aware of the Delancey UK Chess Challenge, which is an important part of the school calendar. Back to base, and it was time for discussions on how to build upon our initial successes.