Change and Continuities: Taiwan's Post-2008 Environmental Policies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement March 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 31 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 38 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 54 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 58 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 65 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 69 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 March 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

List of Insured Financial Institutions (PDF)

401 INSURED FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS 2021/5/31 39 Insured Domestic Banks 5 Sanchong City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 62 Hengshan District Farmers' Association of Hsinchu County 1 Bank of Taiwan 13 BNP Paribas 6 Banciao City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 63 Sinfong Township Farmers' Association of Hsinchu County 2 Land Bank of Taiwan 14 Standard Chartered Bank 7 Danshuei Township Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 64 Miaoli City Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 3 Taiwan Cooperative Bank 15 Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation 8 Shulin City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 65 Jhunan Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 4 First Commercial Bank 16 Credit Agricole Corporate and Investment Bank 9 Yingge Township Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 66 Tongsiao Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 5 Hua Nan Commercial Bank 17 UBS AG 10 Sansia Township Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 67 Yuanli Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 6 Chang Hwa Commercial Bank 18 ING BANK, N. V. 11 Sinjhuang City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 68 Houlong Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 7 Citibank Taiwan 19 Australia and New Zealand Bank 12 Sijhih City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 69 Jhuolan Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 8 The Shanghai Commercial & Savings Bank 20 Wells Fargo Bank 13 Tucheng City Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 70 Sihu Township Farmers' Association of Miaoli County 9 Taipei Fubon Commercial Bank 21 MUFG Bank 14 -

The Offshore Wind Energy Sector in Taiwan

THE OFFSHORE WIND ENERGY SECTOR IN TAIWAN The Offshore Wind Power Industry in Taiwan Flanders Investment & Trade Taipei Office The Offshore Wind Power Industry in Taiwan | 01/2014 ____________________________________________________ 3 1. CONTENTS 2. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................... 7 3. CURRENT ONSHORE WIND POWER IN TAIWAN ............................................... 8 4. CURRENT OFFSHORE WIND POWER DEVELOPMENT IN TAIWAN ....................... 10 A. OFFSHORE WIND POTENTIAL ................................................................... 10 B. TAIWAN’S TARGETS & EFFORTS FOR DEVELOPING WIND ENERGY ................. 11 C. LOCALIZATION OF SUPPLY CHAIN TO MEET LOCAL ENVIRONMENT NEEDS ...... 16 5. MAJOR PLAYERS IN TAIWAN ....................................................................... 17 A. GOVERNMENT AGENCIES ......................................................................... 17 B. MAJOR WIND FARM DEVELOPERS ............................................................. 18 C. MAJOR R&D INSTITUTES, INDUSTRIAL ASSOCIATIONS AND COMPANIES ........ 19 6. INTERACTION BETWEEN BELGIUM AND TAIWAN ............................................ 23 The Offshore Wind Power Industry in Taiwan | 01/2014 ____________________________________________________ 5 2. INTRODUCTION Taiwan is an island that highly relies on imported energy (97~99%) to sustain the power supply of the country. Nuclear power was one of the solutions to be pursued to resolve the high dependency of the -

Evaluation of Liquefaction Potential and Post-Liquefaction Settlement of Tzuoswei River Alluvial Plain in Western Taiwan

Missouri University of Science and Technology Scholars' Mine International Conference on Case Histories in (2008) - Sixth International Conference on Case Geotechnical Engineering Histories in Geotechnical Engineering 16 Aug 2008, 8:45am - 12:30pm Evaluation of Liquefaction Potential and Post-Liquefaction Settlement of Tzuoswei River Alluvial Plain in Western Taiwan C. P. Kuo National Taiwan University of Science & Technology, Taipei, Taiwan, China M. Chang National Yunlin University of Science & Technology, Yunlin, Taiwan, China R. E. Hsu National Yunlin University of Science & Technology, Yunlin, Taiwan, China S. H. Shau National Yunlin University of Science & Technology, Yunlin, Taiwan, China T. M. Lin National Yunlin University of Science & Technology, Yunlin, Taiwan, China Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/icchge Part of the Geotechnical Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Kuo, C. P.; Chang, M.; Hsu, R. E.; Shau, S. H.; and Lin, T. M., "Evaluation of Liquefaction Potential and Post- Liquefaction Settlement of Tzuoswei River Alluvial Plain in Western Taiwan" (2008). International Conference on Case Histories in Geotechnical Engineering. 8. https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/icchge/6icchge/session03/8 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article - Conference proceedings is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars' Mine. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Conference on Case Histories in Geotechnical Engineering by an authorized administrator of Scholars' Mine. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -

China National Accord Medicines Corporation Ltd

China National Accord Medicines Corporation Ltd. Semi-Annual Report 2020 August 2020 1 Section I. Important Notice, Contents and Interpretation Board of Directors, Supervisory Committee, all directors, supervisors and senior executives of China National Accord Medicines Corporation Ltd. (hereinafter referred to as the Company) hereby confirm that there are no any fictitious statements, misleading statements, or important omissions carried in this report, and shall take all responsibilities, individual and/or joint, for the reality, accuracy and completion of the whole contents. Lin Zhaoxiong, Principal of the Company, Gu Guolin, person in charger of accounting works and Wang Ying, person in charge of accounting organ (accounting principal) hereby confirm that the Financial Report of Semi- Annual Report 2020 is authentic, accurate and complete. Other directors attending the Meeting for annual report deliberation except for the followed: Name of director absent Title for absent director Reasons for absent Attorney Lian Wanyong Director Official business Li Dongjiu The Company plans not to pay cash dividends, bonus and carry out capitalizing of common reserves. 2 Contents Semi-Annual Report 2020..................................................................................................................2 Section I Important Notice, Contents and Interpretation.............................................................. 2 Section II Company Profile and Main Financial Indexes...............................................................5 -

Development of Digital Maker Education from Elementary School to University

Development of Digital Maker Education from Elementary School to University (Courtesy of Zong-Hua Cai at the Division of Student Affairs and Campus Security) To improve teachers' teaching ability in digital maker education, the Ministry of Education has entrusted the National Kaohsiung Normal University (NKNU) as the general coordinator in the promotion of the STEM + A Course-Oriented Digital Maker Education Development Program. With the integration of three subprograms in northern, central, and southern Taiwan and the bases in line with the “star- planet-satellite” model, schools with the willingness to participate are guided to implement digital maker education. Sun-Lu Fan, Political Deputy Minister of Education, said that we were currently in a hands-on era and that the development of digital maker education into formal courses and the common version of teaching aids were very helpful for teaching sites in the front line. Schools that have received subsidiaries for teaching aids will, in the initial period, incorporate the common teaching aids developed by universities into their instruction under the new curriculum guidelines. It is expected that, eventually there will be at least 72 "micro courses" being developed, incorporating digital maker education in various subject areas at the end of the year. 1 Fu-Yuan Peng, Director-General of K-12 Education Administration of the Ministry of Education also encouraged all senior high schools to participate actively. Among them, National Yeong-Jing Industrial Vocational High School (YJVS) in Changhua County participates in the subprogram in central Taiwan; the teachers are being provided with guidance and support by the bases at the “star” level staffed by personnel from NKNU and the National Chung Hsing University (NCHU). -

Cyberfair 2017 Winners List

CyberFair 2017 Winners List Global SchoolNet’s International CyberFair engages students in powerful educational story-telling activities, which benefit students and their communities. Enjoy your virtual journey around the globe and learn how education can unite people, increase understanding, and strengthen communities. Congratulations to all 2017 International CyberFair students, teachers, and community members! http://globalschoolnet.org/gsncf +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ 2017 CATEGORY 1: Local Leaders +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ ================================================================ PLATINUM AWARD: CATEGORY 1 ================================================================ -------------------------------------------------------------: Project ID 8204: SULTAN jOHOR Category: 1. Local Leaders SJK T LADANG SEGAMAT SEGAMAT, MALAYSIA ------------------------------------------------------------- Project ID 8229: Amis Ifu -You are So Powerful. Category: 1. Local Leaders Taipei City Science and Technology School TAIWAN ------------------------------------------------------------- Project ID 8244: The Universe in a Grain of Sand-The Miniature & Brick Carving of Chen Forng-Shean Category: 1. Local Leaders Chi-Jen Primary School New Taipei City, TAIWAN ------------------------------------------------------------- Project ID 8294: Bright Spot on the Street -- Illusionist Jerry Huang Category: 1. Local Leaders Lukang Junior High School Changhua, TAIWAN ------------------------------------------------------------- -

An Environment Study of the Offshore Wind Farm in the Central Taiwan and the Planning of Fabrication Yard

臺灣中部風場海域環境及 施工碼頭規劃概況 An Environment Study Of The Offshore Wind Farm in The Central Taiwan and The Planning of Fabrication Yard 1 Contents 2016/10/27 The first offshore wind turbine in Taiwan The Situation of Offshore Wind SIEMENS 4MW farm in Taiwan Environmental Conditions in Changhua Offshore The planning of fabrication yard in Taichung Port Brief Introduction of Sinotech Engineering Consultants,Ltd 2 The Situation of Offshore Wind farm in Taiwan 3 Potential Wind Energy in Taiwan •Water depth:5~20m Area:1,779.2 km2 Total Potential:9 GW Exploitation:1.2 GW •Water depth:20~50m Area:6,547 km2 Total Potential:48 GW Exploitation :5 GW • Water depth>50m Total Potential :90 GW Exploitation :9 GW Density of Wind Energy(W/m2) 4 4 The Project of Thousand Wind Turbines in Taiwan •Targets Recently : 4 demonstration offshore wind turbines by 2016 Medium : Offshore 520 MW by 2020 Future: Offshore 3,000 MW by 2025, 4,000 MW by 2030 裝置容量 風機 風機 (MW) 裝置容量 岸上 離岸 5 總風力發電裝置容量 5 Offshore Demonstration Incentive Program In 2013.1.25 Energy of Bureau announced: Swancor(Formosa), Taiwan Fuhai Demonstration Case: Generation (Fuhai)and Location: Off the coast of Fangyuan Township, Changhua County Offshore: 8~12 kilometers, Taipower got the license to water depth: 20~45 meters WTs: 30 installed wind turbines exploit the demonstration wind Capacity: About 120 MW Farm. Formosa Demonstration Case: TPC Demonstration Case: Location: Off the coast of Zhunan Location: West side sea area of Fangyuan Township, Township, Miaoli County Changhua County Offshore: -

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 04/01/2013 10:12:17 PM OMB NO

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 04/01/2013 10:12:17 PM OMB NO. 1124-0002; Expires February 28, 2014 u.s. Department of Justice Supplemental Statement Washington, DC 20530 -.;-.--H-- Pursuant to the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, as amended For Six Month Period Ending 2/28/2013 (Insert date) I-REGISTRANT 1. (a) Name of Registrant (b) Registration No. Michael Joseph Fonte 5514 (c) Business Address(es) of Registrant 8 Belmont Court Silver Spring, MD 20910 888 16th Street NW #800 Washington DC 20006 2. Has there been a change in the information previously furnished in connection with the following? (a) If an individual: (1) Residence address(es) Yes • No H (2) Citizenship Yes • No 0 (3) Occupation Yes D No H (b) If an organization: (1) Name Yes D No D (2) Ownership or control Yes • No D (3) Branch offices Yes D No D (c) Explain fully all changes, ifany, indicated in Items (a) and (b) above. IF THE REGISTRANT IS AN INDIVIDUAL, OMIT RESPONSE TO ITEMS 3, 4, AND 5(a). 3. If you have previously filed Exhibit C1, state whether any changes therein have occurred during this 6 month reporting period. Yes • No D If yes, have you filed an amendment to the Exhibit C? YesD NoD If no, please attach the required amendment. 1 The Exhibit C, for which no printed form is provided, consists of a true copy ofthe charter, articles of incorporation, association, and by laws of a registrant that is an organization. (A waiver ofthe requirement to file an Exhibit C may be obtained for good cause upon written application to the Assistant Attorney General, National Security Division, U.S. -

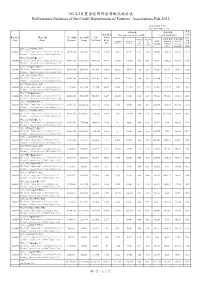

101年2月農會信用部經營概況統計表performance Statistics of The

101年2月農會信用部經營概況統計表 Performance Statistics of the Credit Departments of Farmers’ Associations,Feb-2012 單位:新臺幣 千元,% Unit:NT$1,000 percent 逾期放款 備抵呆帳 淨值 本期損益 Non-performing Loan(NPL) Loan Loss Deposit 佔風 單位代號 單位名稱 存款總額 放款總額 淨值 Profit 險性 占狹義逾期 占廣義逾期 Code Name Deposits Loans Net Worth Before 狹義逾期比 廣義逾期比 資產 狹義逾期放款 廣義逾期放款 率 率 金額 放款比率 放款比率 Tax NPL(Old) NPL(New) NPL NPL Amount Coverage Coverage 比率 Ratio(Old) Ratio(New) Rate Rate(New) BIS 新北市三重區農會信用部 6060019 The Credit Department of Sanchong District 14,893,908 9,490,881 1,519,341 23,458 12,477 38,197 0.13 0.40 134,839 1,080.70 353.01 19.77 Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 新北市板橋區農會信用部 6060020 The Credit Department of Banciao District 40,671,274 29,031,313 4,933,179 34,179 23,354 122,042 0.08 0.42 529,331 2,266.55 433.73 23.54 Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 新北市淡水區農會信用部 6060031 The Credit Department of Danshuei District 10,796,680 5,599,994 591,469 6,839 68,242 165,673 1.22 2.96 97,289 142.56 58.72 12.19 Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 新北市樹林區農會信用部 6060042 The Credit Department of Shulin District 26,288,960 16,453,526 2,532,105 14,477 40,191 95,075 0.24 0.58 311,524 775.11 327.66 16.71 Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 新北市鶯歌區農會信用部 6060053 The Credit Department of Yingge District 9,775,066 6,133,704 973,784 10,077 6,858 112,537 0.11 1.83 89,002 1,297.78 79.09 15.02 Farmers' Association of New Taipei City 新北市三峽區農會信用部 6060064 The Credit Department of Sansia District 10,273,308 5,107,695 560,008 6,667 15,325 64,883 0.30 1.27 89,316 582.81 137.66 12.81 Farmers' Association -

Religion in Modern Taiwan

00FMClart 7/25/03 8:37 AM Page i RELIGION IN MODERN TAIWAN 00FMClart 7/25/03 8:37 AM Page ii TAIWAN AND THE FUJIAN COAST. Map designed by Bill Nelson. 00FMClart 7/25/03 8:37 AM Page iii RELIGION IN MODERN TAIWAN Tradition and Innovation in a Changing Society Edited by Philip Clart & Charles B. Jones University of Hawai‘i Press Honolulu 00FMClart 7/25/03 8:37 AM Page iv © 2003 University of Hawai‘i Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 08 07 0605 04 03 65 4 3 2 1 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Religion in modern Taiwan : tradition and innovation in a changing society / Edited by Philip Clart and Charles B. Jones. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8248-2564-0 (alk. paper) 1. Taiwan—Religion. I. Clart, Philip. II. Jones, Charles Brewer. BL1975 .R46 2003 200'.95124'9—dc21 2003004073 University of Hawai‘i Press books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Council on Library Resources. Designed by Diane Gleba Hall Printed by The Maple-Vail Book Manufacturing Group 00FMClart 7/25/03 8:37 AM Page v This volume is dedicated to the memory of Julian F. Pas (1929–2000) 00FMClart 7/25/03 8:37 AM Page vi 00FMClart 7/25/03 8:37 AM Page vii Contents Preface ix Introduction PHILIP CLART & CHARLES B. JONES 1. Religion in Taiwan at the End of the Japanese Colonial Period CHARLES B. -

Case Study of Fangyuan Township, Chunghua County, Taiwan

Journal of Marine Science and Technology, Vol. 27, No. 5, pp. 427-434 (2019) 427 DOI: 10.6119/JMST.201910_27(5).0005 PERCEPTIONS OF OFFSHORE WIND FARMS AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT: CASE STUDY OF FANGYUAN TOWNSHIP, CHUNGHUA COUNTY, TAIWAN Ku-Jung Lin1,2, Chia-Pao Hsu1, and Hung-Yu Liu1 Key words: Offshore Wind Farms (OWF), green energy develop- of Fangyuan for providing community benefits by reviving the ment, community engagement, stakeholder empower- local culture and encouraging tourism based on both tradi- ment, traditional industries, community-based tourism tional activities and OWF appeared to be received favorably by all involved. ABSTRACT I. INTRODUCTION Surrounded by the ocean, Taiwan has many rich marine A search for new sources of clean energy to mitigate the cultural resources that have benefited its coastal communities prospect of climate changes is now underway. The power grid and led to the development of diverse traditional marine in- is undergoing a transformation as countries across the globe dustries. A typical example is the unique tradition of “Sea seek to achieve zero emissions for power systems before the Buffalos Working in the Oyster Field”, which has been prac- year 2050 (IPCC, 2018). Owing to uncertainty in the global ticed for over a century in Fangyuan Township of Changhua power market, and also due to changes in the renewable en- County. The cultural landscape of buffalos and workers cul- ergy policies of various nations, the detailed outlook for the tivating oyster fields has been recognized as a precious cul- wind power industry is unpredictable; however, wind power tural heritage by both local and international parties.