Pseudonymous Litigation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chivalry in Western Literature Richard N

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses 2012 The nbU ought Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature Richard N. Boggs Rollins College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, European History Commons, Medieval History Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Boggs, Richard N., "The nbouU ght Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature" (2012). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 21. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/21 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Unbought Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature A Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies by Richard N. Boggs May, 2012 Mentor: Dr. Thomas Cook Reader: Dr. Gail Sinclair Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Master of Liberal Studies Program Winter Park, Florida The Unbought Grace of Life: Chivalry in Western Literature By Richard N. Boggs May, 2012 Project Approved: ________________________________________ Mentor ________________________________________ Reader ________________________________________ Director, Master of Liberal Studies Program ________________________________________ Dean, Hamilton Holt School Rollins College Dedicated to my wife Elizabeth for her love, her patience and her unceasing support. CONTENTS I. Introduction 1 II. Greek Pre-Chivalry 5 III. Roman Pre-Chivalry 11 IV. The Rise of Christian Chivalry 18 V. The Age of Chivalry 26 VI. -

A Paul Harris Fellow Is a Person Who Has Been Recognized As Having Done Something Significant for Others

PAUL HARRIS FELLOW A Paul Harris Fellow is a person who has been recognized as having done something significant for others. The Foundation recognizes them for the contribution of $ 1000, which will be spent on Humanitarian efforts around the world. A club recognizes them for service to the club and or the community. Individual Paul Harris Fellows recognize others for many reasons; admiration, service, love or whatever. In ALL cases the recognition is significant and something to be proud of. Who was Paul Harris? Paul Harris was the founder and organizer of the first Rotary Club in Chicago in 1905. He was founder of the Rotary idea, and the first president of the worldwide organization, Rotary International. Paul Harris died in 1947. Upon his death, memorial gifts poured in to honor the founder of Rotary. From that time, the Rotary Foundation has been achieving the noble objective of furthering “understanding and friendly relations between peoples of different nations”. In 1957, the idea of Paul Harris Fellow (PHF) recognition was first proposed as a means to promote voluntary giving to the Rotary Foundation. Although the concept of making $1,000 gifts to the Foundation was slow in developing, by the early 1970s the program began to gain popularity. The distinctive Paul Harris Fellow medallion, lapel pin and certificate have become highly respected symbols of a substantial commitment to The Rotary Foundation by Rotarians and friends around the world. Individual Members are encouraged to make contributions to The Foundation to gain Paul Harris Fellow recognition. Alternatively, many clubs provide recognition for outstanding service by contributing in the name of a Rotary member or in the name of a citizen of the community. -

Fellow Program

HARPER COLLEGE DIVERSE FACULTY Fellow Program “Diversity drives innovation. When we limit who can contribute, we in turn limit what problems we can solve.” – TELLE WHITNEY The Harper College Diverse Faculty Fellow Program opens the door to individuals of historically underrepresented groups so they may gain extensive, valuable experience as a college faculty member. 2 OPENING DOORS TO Experiential Opportunities OR FUTURE FACULTY. Our students, our College, and our society will gain significant advantages as we continue to nurture a richly diverse faculty who are motivated to inspire our increasingly diverse student population. Consider This Opportunity If You’re: • A thinker who believes in the community college mission and want to help change lives. • An individual with minimal or no teaching experience but desire to motivate and educate others to achieve their goals. • A person who wants to share your perspective with our College and in our classrooms. • A leader with a desire to recognize and celebrate the value of diversity in academia. • A motivated academic or individual who is hungry for mentorship by seasoned faculty professionals and willing to build a portfolio of credentials. • An individual who has completed a Master’s degree or Doctorate in a discipline or related area that corresponds with educational departments at Harper College. Special consideration will be given to applicants who have been historically underrepresented in faculty positions in higher education. If you’re not sure if this is for you, let’s talk. We invite you to email the Office of Diversity and Inclusion at [email protected] to schedule a personal conversation about a future opportunity. -

Award of Emeritus/Emerita Professor, Emeritus Fellow and Honorary University Fellow Titles

Award of Emeritus/Emerita Professor, Emeritus Fellow and Honorary University Fellow Titles Overview Scope and Application Policy Principles 1. Emeritus Professor 2. Emeritus Fellow 3. Honorary University Fellow 4. Report to Council 5. Use of Title Procedures Definition OVERVIEW The policy provides for the award of emeritus titles to honour and acknowledge distinguished and sustained service to the University. SCOPE AND APPLICATION This policy applies to academic & professional staff and members of the broader university community who have given distinguished and sustained service to the University. POLICY PRINCIPLES Emeritus Professor The title “Emeritus Professor”, or at the request of the conferee “Emerita Professor”, may be conferred on professors for distinguished and sustained service to the University: a) on their retirement; or b) on their leaving the University to take up an appointment elsewhere when they are unlikely to return to the University of Adelaide to work. Emeritus Fellow The award of “Emeritus Fellow”, or at the request of the conferee “Emerita Fellow”, will be exceptional in nature and may be conferred on academic or professional staff for distinguished and sustained service which is demonstrably beyond the level of service usually expected of a senior staff member: a) on their retirement; or b) on their leaving the University to take up an appointment elsewhere when they are unlikely to return to the University of Adelaide to work. Honorary University Fellow The award of “Honorary University Fellow” will be exceptional in nature and may be conferred on a member of the broader University community to recognise significant meritorious service to the University. -

Postdoctoral Research Fellow Handbook V2018-08-06

FONTS USED PROMINENT COLORS C=96 M=20 Y=63 K=00 R=00 G=147 B=127 HEX = 00927e C=73 M=00 Y=37 K=00 R=15 G=186 B=178 HEX = 0ebab2 C=35.87 M=00 Y=16.04 K=00 R=160 G=217 B=217 HEX = a0d9d8 UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA HEALTH SCIENCES CENTER GRADUATE COLLEGE OFFICE OF POSTDOCTORAL AFFAIRS POSTDOCTORAL RESEARCH FELLOW HANDBOOK Effective date: August 6, 2018 Page 1 of 16 POSTDOCTORAL RESEARCH FELLOW HANDBOOK TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction II. Procedure for Advertising a Postdoctoral Research Fellow Position III. Types of Postdoctoral Research Fellow Appointments 1. Postdoctoral Research Fellow 2. NRSA Postdoctoral Research Fellow 3. Part-time Postdoctoral Research Fellow IV. Salary V. Procedure for Appointing a Postdoctoral Research Fellow VI. Length of Appointment of a Postdoctoral Research Fellow VII. Benefits 1. Health Insurance 2. Leave 3. Holiday Pay 4. Professional Leave 5. Voluntary Retirement Plans 6. Absence from Work Due to the Family & Medical Leave Act (FMLA) 7. Extended Leave 8. Part-time Benefit-eligible Postdoctoral Research Fellows VIII. Career Development IX. Enrollment in OUHSC Coursework X. Performance Evaluation Termination of Employment 1. Satisfactory Conditions 2. Reduction in Force 3. Termination due to Unsatisfactory Performance XI. When Things Do Not Go Well XII. Postdoctoral Research Fellow Grievance Procedure XIII. Conflict of Interest Effective date: August 6, 2018 Page 2 of 16 I. INTRODUCTION The Postdoctoral Research Fellow (Postdoctoral Fellow) position is a limited time trainee position for a qualified individual who has obtained a PhD or appropriate professional degree. This is a temporary appointment carrying no academic rank. -

Boston College Postdoctoral Research Fellow Policy

September 28, 2018 Boston College Postdoctoral Research Fellow Policy Introduction Boston College (“the University”) recognizes the importance of assisting Postdoctoral Research Fellows (“Postdoc Fellows”) as they develop into independent investigators. Postdoc Fellow appointments offer advanced degree recipients a period in which to extend their education and professional training. The breadth of the academic community together with the physical resources in its libraries and laboratories make the University an ideal environment for postdoctoral training. While the University seeks to provide Postdoc Fellows with the opportunity to continue their academic training through on-site practice experience, many aspects of the relationship between the University and its Postdoc Fellows are also that of an employer- employee relationship. Therefore, the University has adopted this Postdoctoral Research Fellow Policy (the “Policy”) to delineate the obligations and expectations of all parties involved in Postdoc Fellow training. All Postdoc Fellows and Faculty Mentors must comply with the requirements set forth in this Policy. Any questions about the Policy should be directed to the University’s Office of the Vice Provost for Research (“VPR”). 1. Definition, Purpose, and Eligibility of Postdoctoral Research Fellow 1.1 Definition and Purpose: A Postdoctoral Research Fellow is an individual holding a doctoral degree or equivalent who is engaged in a temporary period of mentored research and/or scholarly training. The principal purpose of a Postdoc Fellow appointment is to acquire the professional skills needed to pursue an independent career path of the Postdoc Fellow’s choosing. A Postdoc Fellow is an employee of the University and shall work under the direct supervision and mentorship of the Faculty Mentor. -

Practitioner Acronym Table

Practitioner Acronym Table AAP American Academy of Pediatrics ABAI American Board of Allergy and Immunology ABFP American Board of Family Practitioners ABO American Board of Otolaryngology ABPN American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology AK Acupuncturist (Pennsylvania) AOBFP American Osteopathic Board of Family Physicians American Osteopathic Board of Special Proficiency in Osteopathic Manipulative AOBSPOMM Medicine AP Acupuncture Physician ASG Affiliated Study Group BHMS Bachelor of Homeopathic Medicine and Surgery BSN Bachelor of Science, Nursing BVScAH Bachelor of Veterinary Science and Animal Husbandry CA Certified Acupuncturist CAAPM Clinical Associate of the American Academy of Pain Management CAC Certified Animal Chiropractor CCH Certified in Classical Homeopathy CCSP Certified Chiropractic Sports Physician CRNP Certified Registered Nurse Practitioner CRRN Certified Rehabilitation Registered Nurse CSPOMM Certified Specialty of Proficiency in Osteopathic Manipulation Medicine CVA Certified Veterinary Acupuncturist DAAPM Diplomate of American Academy of Pain Management DABFP Diplomate of the American Board of Family Practice DABIM Diplomate of the American Board of Internal Medicine DAc Diplomate in Acupuncture DAc (RI) Doctor of Acupuncture, Rhode Island DAc (WV) Doctor of Acupuncture, West Virginia DACBN Diplomate of American Chiropractic Board of Nutrition DACVD Diplomate of the American College of Veterinary Dermatology DC Doctor of Chiropractic DDS Doctor of Dentistry DHANP Diplomate of the Homeopathic Academy of Naturopathic -

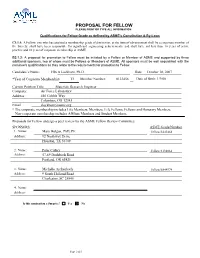

Proposal for Fellow Please Print Or Type All Information

PROPOSAL FOR FELLOW PLEASE PRINT OR TYPE ALL INFORMATION Qualifications for F ellow Grade a s defined b y ASM E’s Con stitution & B y -Laws C3.1.4: A Fellow, one who has attained a membership grade of distinction, at the time of advancement shall be a corporate member of the Society, shall have been responsible for significant engineering achievements, and shall have not less than 10 years of active practice and 10 years of corporate membership in ASME. B3.1.2: A proposal for promotion to Fellow must be initiated by a Fellow or Member of ASME and supported by three additional sponsors, two of whom must be Fellows or Members of ASME. All sponsors must be well acquainted with the nominee's qualifications as they relate to the requirements for promotion to Fellow Candidate’s Name: Elbe rt Lockhorn, Ph.D. Date: October 10, 2007 *Year of Corporate Membershi p: 13 Member Number: 0123456 Date of Birth: 1/9/60 Current Position Title: Materials Research Engineer Company: Air Force L aboratory Address: 456 Cobble Way Columbus, OH 12345 Email [email protected] * The corporate membership includes Life Members, Members, Life Fellows, Fellows and Honorary Members. Non-corporate membership includes Affiliate Members and Student Members. Proposals for Fellow undergo a peer review by the ASME Fellow Review Committee. SPONSORS: ASME Grade/Number 1. Name: Mary Holgan, PhD, PE Fellow/5443468 Address: 92 Northway Drive Houston, TX 56789 2. Name: Peter Colbry Fellow/3134864 Address: 57-69 Duckback Road Portland, OR 65421 3. Name: Michelle Archenbach Fellow/6844974 Address: 9 South Holland Road Charleston, SC 25945 4. -

Americorps Promise Fellow Placement Site

2020-2021 AMERICORPS PROMISE FELLOW POSITION DESCRIPTION Title: AmeriCorps Promise Fellow Placement Site: Breakthrough Twin Cities Contact: Pa Kou Lee, Program Manager, [email protected], (651) 748-5592 Position Type: 1700 Hours Minimum Required, serving in a 40 Hours/Week capacity Site Highlight Want to make an impact in educational equity? At Breakthrough Twin Cities we empower students and families on the college path through high expectations and individualized support. You could be the “breakthrough” in a student’s life, connecting students with school & community resources and opportunities to inspire success. Breakthrough Twin Cities Promise Fellow Responsibilities Promise Fellows will organize field trips and other special events to make learning and being at school more engaging and relevant to youth who are disengaged and at risk of dropping out. Fellows will conduct outreach to community and program partners to organize resources and materials that support our students and families (translation and interpreting services, tutoring, school options, counseling, family services, etc). AmeriCorps Promise Fellow Position Responsibilities Build and foster strong relationships with their selected students. Coordinate and deliver in and out of school time academic enrichment activities with the goal that at least 30 youth in grades 6-12 will experience academic gains. Meet regularly with Youth Success Team to review data and identify youth to serve; track student progress; and determine which interventions to connect to individual students or groups of students. Develop and organize projects that engage youth participants in service and leadership activities. Recruit and/or support community volunteers, including family members, to work with youth participants in areas such as mentoring, tutoring, civic engagement, and college/career exploration. -

Council Regulations Chartered Institute of Ergonomics and Human Factors

CIEHF Council Regulations Chartered Institute of Ergonomics and Human Factors COUNCIL REGULATIONS The Chartered Institute, hereinafter called the Institute, is established to fulfil the objectives defined in the Charter and in accordance with the Byelaws. The rules and operating procedures are defined in the General Regulations and their Appendices (Code of Conduct, Disciplinary Regulations and Roles of the Executive Officers of the Institute) and these Council Regulations and their Appendices. 1. In the event of any inconsistency between the provisions of the Charter, the provisions of the Byelaws, the provisions of the General Regulations and these Council Regulations, the provisions of the Charter, the Byelaws and the General Regulations shall prevail. The Charter, Byelaws, General Regulations and Council Regulations of the Institute shall be publicly available. Membership Titles and Post‐Nominals 2. The criteria and procedures for accrediting applicants to the Institute’s grades of membership are prescribed in the Rules of the Professional Affairs Board (‘PAB’) 3. Members of the Body Corporate so accredited may use the following titles and post‐nominals. Honorary Fellows, Fellows and Registered Members who had the right to use previous titles and post‐nominals will be encouraged to change to these titles and post‐nominals: Registered Members may use the title ‘Registered Member of the Chartered Institute of Ergonomics and Human Factors’ and the designatory letters ‘MCIEHF’ after their name. Fellows may use the title ‘Fellow of the Chartered Institute of Ergonomics and Human Factors’ and the designatory letters ‘FCIEHF’ after their name. Honorary Fellows may use the title ‘Honorary Fellow of the Chartered Institute of Ergonomics and Human Factors’ and the designatory letters ‘Hon.FCIEHF’ after their name. -

Bronze Medal Award I. DEFINITION and HISTORY the Honor Of

Bronze Medal Award I. DEFINITION AND HISTORY The honor of Bronze Medal of the Society recognizes ASM members who are in early-career positions, typically, 0 to 10 years of experience, for their significant contributions in the field of materials science & engineering through technical content and service to ASM and the materials science profession. The Bronze Medal Award recognizes outstanding young professionals and encourages individual growth and further contributions to the profession as well as the Society. Candidates for the Bronze Medal Award will have made significant technical contributions to the society, may be beyond their eligibility period for the Emerging Professional Achievement Award, and are not yet considered experienced enough to be eligible for the Silver Medal Award. This award serves to recognize and encourage members 35 years of age or less, many of whom have demonstrated notable interest in the Emerging Professional Achievement Award. Annually, up to two individuals (one academic and one non-academic) may be selected to receive the ASM Bronze Medal based on commendable personal reputation and significant technical accomplishments in some phase of materials science, engineering, production, manufacturing, design, and technology transfer, application of technology, and development, research or education as well as service to ASM and the profession of materials science. Judging will be based on two equally weighted criteria: 1) significant technical accomplishments in the field of materials science and engineering; and 2) volunteer professional service, through ASM. It is ASM’s commitment to be inclusive and mindful of diversity in our policies, programs, courses, awards, and interactions with others. As an organization, we affirm and encourage nominations of qualified candidates, within each award's criteria, regardless of their age, culture, ethnic origin, gender, gender identity, marital status, nationality, race, religion, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic status. -

Fellow of the Academy of Wilderness Medicine™ (FAWM) Will Uphold the WMS and AWM Code of 4

“How does the program work?” For accomplished individuals who desire: Membership in the Academy is open to all WMS members. After submitting the application and application fees, candidates participate in eligible activities, such as conferences and CME courses. • Distinction for professional education in wilderness medicine The Academy documents this participation until all requirements are completed. Additionally, Combining your profession with your passion™ • Validation for the public, patients, and clients of training in candidates record professional, academic, volunteer, and other wilderness medical experience wilderness medicine with the Experience Report. Completion of this report ensures that a member’s wilderness medical experience is thorough and well-rounded. • Recognition for completing high-quality standards in wilderness medicine Candidates may take up to five years from the original application date to complete the following requirements: • 100 total credits of training and experience composed of: The Wilderness can mean beauty, recreation, opportunity, and the thrill • 60 minimum to 80 maximum credits from the Core Curriculum (55 min. to 70 max. required topics, 5 min. to 10 max. elective topics) of the unknown, but few expect to face a wild-animal attack, exposure, • 20 min. to 40 max. credits from the Experience Summary Report illness, or traumatic injury. Additionally, events in any location—rural or • Verification of medical training credential appropriate to the candidate’s medical vocation or urban—can require wilderness