AC31 Doc. 18.2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report of Lahore Zoo 2013

Lahore Zoo Established 1872 ANNUAL REPORT OF LAHORE ZOO 2013 No of species 121 No of animals & birds 914 BIRTH, MORTALITY & TRANSFER OF ANIMALS DURING THE YEAR 2013 NAME BIRTH / MORTALITY RECEIVED Animals 83 33 Birds 174 89 First time birth of Demoiselle Crane chick in captivity. New Zoo Management Committee constituted under the Chairmanship of Director General, Wildlife & Parks under the provisions of Punjab Zoos and Safari Parks, Rules 2012, having 4 officials and 5 non-official members. 1st meeting took place on April 30, 2013. Professional and proper management of assets of Lahore zoo INCOME (2013) EXPENDITURE (2013) SAVING 8,83,02,952 7,29,26,933 1,53,76,019 3-years comparison of visitors 2011 2012 2013 32,14,835 36,25,527 39,16,423 Record Income i. Eid-ul-Fitr 2013 Rs.2.647 million ii. Eid-ul-Azha 2013 Rs. 2.251 million iii. Remarkable increase in number of visitors as compared to 2011 and 2012. SUCCESS STORIES ZEBRA FOALS HEALED: In September, 2013, two of the zebra foals were found suffering from a bilateral nasal discharge alongwith submandibular swellings. The sick animals were immediately captured for the collection of blood and nasal samples. Treatment was initiated and the animals were darted on daily basis to ensure a regular administration of antibiotic followed by a couple of physical captures for the drainage and dressings of submandibular abscesses. A visit of the team of veterinaries from UVAS and VRI was also arranged for an expert advice and they also suggested the continuity of the ongoing treatment protocol. -

Margallah Hills National Park.Pdf

i Cover page design: Irfan Ashraf, GIS Laboratory, WWF – Pakistan Photo Credits: Kaif Gill and Naeem Shahzad, GIS Laboratory, WWF - Pakistan ii Contents Contents.............................................................................................................................iii List of Figures ...................................................................................................................iv List of Tables.....................................................................................................................iv List of Abbreviations .........................................................................................................v Acknowledgments .............................................................................................................1 Summary ............................................................................................................................2 1 INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................3 1.1 Background..........................................................................................................3 1.2 Study Area ...........................................................................................................4 2 MATERIALS AND METHODS ................................................................................6 2.1 Satellite Data Procurement ...............................................................................6 2.2 Software Used.....................................................................................................7 -

Status and Red List of Pakistan's Mammals

SSttaattuuss aanndd RReedd LLiisstt ooff PPaakkiissttaann’’ss MMaammmmaallss based on the Pakistan Mammal Conservation Assessment & Management Plan Workshop 18-22 August 2003 Authors, Participants of the C.A.M.P. Workshop Edited and Compiled by, Kashif M. Sheikh PhD and Sanjay Molur 1 Published by: IUCN- Pakistan Copyright: © IUCN Pakistan’s Biodiversity Programme This publication can be reproduced for educational and non-commercial purposes without prior permission from the copyright holder, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior permission (in writing) of the copyright holder. Citation: Sheikh, K. M. & Molur, S. 2004. (Eds.) Status and Red List of Pakistan’s Mammals. Based on the Conservation Assessment and Management Plan. 312pp. IUCN Pakistan Photo Credits: Z.B. Mirza, Kashif M. Sheikh, Arnab Roy, IUCN-MACP, WWF-Pakistan and www.wildlife.com Illustrations: Arnab Roy Official Correspondence Address: Biodiversity Programme IUCN- The World Conservation Union Pakistan 38, Street 86, G-6⁄3, Islamabad Pakistan Tel: 0092-51-2270686 Fax: 0092-51-2270688 Email: [email protected] URL: www.biodiversity.iucnp.org or http://202.38.53.58/biodiversity/redlist/mammals/index.htm 2 Status and Red List of Pakistan Mammals CONTENTS Contributors 05 Host, Organizers, Collaborators and Sponsors 06 List of Pakistan Mammals CAMP Participants 07 List of Contributors (with inputs on Biological Information Sheets only) 09 Participating Institutions -

1.Punjab Tourism for Economic Growth.Cdr

Punjab Tourism for Economic Growth Consortium for c d p r Development Policy Research w w w . c d p r . o r g . p k c d p r Report R1703 State June 2017 About the project The final report Punjab Tourism for Economic Growth has been completed by the CDPR team under overall guidance Funded by: World Bank from Suleman Ghani. The team includes Aftab Rana, Fatima Habib, Hina Shaikh, Nazish Afraz, Shireen Waheed, Usman Key Counterpart: Government of Khan, Turab Hussain and Zara Salman. The team would also +924235778180 [email protected] Punjab like to acknowledge the advisory support provided by . Impact Hasaan Khawar and Ali Murtaza. Dr. Ijaz Nabi (IGC,CDPR) With assistance from provided rigorous academic oversight of the report. CDPR, Government of Punjab has formulated a n d a p p r o v e d k e y principles of policy for tourism, providing an In brief anchor for future reforms Ÿ Government of Punjab is keen and committed to and clearly articulating i t s c o m m i t m e n t t o developing a comprehensive strategy for putting p r o m o t e t o u r i s m , tourism on a solid footing. e s p e c i a l l y h e r i t a g e Ÿ CDPR has been commissioned by the government to tourism. Government of help adopt an informed, contemporary, view of tourism Punjab has been closely involved in formulation of and assist in designing a reform program to modernize www.cdpr.org.pk f o l l o w - u p the sector. -

Compendium on Environment Statistics of Pakistan - 2004

Compendium on Environment Statistics of Pakistan - 2004 Federal Bureau of Statistics Government of Pakistan i Foreword As an inescapable concomitant with the traditional route of development, Pakistan has been facing natural resource degradation and pollution problems. The unsavory spectacle of air pollution, water contamination and other macro environmental impacts such as water logging, land degradation and desertification, are on rise. All this, in conjunction with rapid growth in population, has been instrumental to the expanding tentacles of poverty. In order to make an assessment of the environmental problems as a prelude to arrest the pace of degeneration and, provide for sustainable course of economic development, the availability of adequate data is imperative. This publication is an attempt to provide relevant statistics compiled through secondary sources. The 1st Compendium was prepared in 1998 under the Technical Assistance of Asian Development Bank in accordance with, as far as possible, the guidelines of “United Nations Framework for Development of Environment Statistics (FDES)”. This up-dating has been made without any project facilitation. Notwithstanding exclusive reliance on mail inquiry, all possible efforts have been made to collect available data and, quite a few new tables on quality of water, concentration of dust fall in big cities and, state of air quality in urban centers of Punjab, have also been included in the compendium. However, some tables included in the predecessor of this publication could not be up-dated due either to their being single time activity or the source agencies did not have the pertinent data. The same have been listed at appendix-IV to refer compendium-1998 for the requisite historical data. -

Business Structure Finan High

OVERVIEW PERFORMANCE SUSTAINABILITY FINANCIALS APPENDIX BUSINESS FINANCIAL STRUCTURE HIGHLIGHTS REVENUE (S$’m) EARNINGS BEFORE INTEREST AND TAX (“EBIT”) (S$’m) 2016 110.2 2016 111.2 2017 74.5 2017 219.6 2018 78.3 2018 376.2 REAL ESTATE BUSINESS HEALTHCARE BUSINESS MANAGEMENT BUSINESS 2019 124.2 2019 136.0 2020 111.2 2020 111.7 FY2020 revenue decreased by 10.5% mainly due to the impact FY2020 EBIT decreased by 17.8% mainly due to lower fair value China Singapore Hospitals/ Asset Management Medical Centres Ownership arising from COVID-19, which includes lower revenue from The gains and Employee Share Option Scheme paid out in FY2020. Development/ Capitol Kempinski Hotel Singapore, lower occupancy rate from Fair value gains at the EBIT level totalled S$2.1m in FY2020 as Integrated Integrated Perennial 90% Project Management Capitol Singapore, CHIJMES, Perennial Jihua Mall and Perennial compared to S$66.4m in FY2019. The decrease was mitigated by Developments Ownership Developments Ownership International International Health and Medical Hub. Higher rental rebates remeasurement gain and bargain purchase for Beijing Tongzhou Specialist Medical Property Management granted to Capitol Singapore and CHIJMES’ tenants also Integrated Development Phase 2 acquisition, as well as gain on Chengdu East Perennial 80% Capitol 100% Centre Singapore contributed to the lower revenue in FY2020. disposal of Zhuhai Hengqin Integrated Development, 111 High Speed International Hospital Management Railway Integrated Health and Eldercare and Somerset and AXA Tower. Development Medical AXA Tower 10% Senior Housing Ownership Hub Hotel Management Retail Malls/ Plot C 50% Shanghai 49.9% PROFIT AFTER TAX AND MINORITY INTEREST (“PATMI”) EARNINGS PER SHARE (“EPS”) Commercial Renshoutang Plot D1 50% Eldercare Group (S$’m) (cents) CHIJMES 51.6%1 Plot D2 50% Co., Ltd. -

Punjab Tourism for Economic Growth Final Report Consortium for Development Policy Research

Punjab Tourism for Economic Growth Final Report Consortium for Development Policy Research ABSTRACT This report documents the technical support provided by the Design Team, deployed by CDPR, and covers the recommendations for institutional and regulatory reforms as well as a proposed private sector participation framework for tourism sector in Punjab, in the context of religious tourism, to stimulate investment and economic growth. Pakistan: Cultural and Heritage Tourism Project ---------------------- (Back of the title page) ---------------------- This page is intentionally left blank. 2 Consortium for Development Policy Research Pakistan: Cultural and Heritage Tourism Project TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS & ABBREVIATIONS 56 LIST OF FIGURES 78 LIST OF TABLES 89 LIST OF BOXES 910 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1011 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1112 1 BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT 1819 1.1 INTRODUCTION 1819 1.2 PAKISTAN’S TOURISM SECTOR 1819 1.3 TRAVEL AND TOURISM COMPETITIVENESS 2324 1.4 ECONOMIC POTENTIAL OF TOURISM SECTOR 2526 1.4.1 INTERNATIONAL TOURISM 2526 1.4.2 DOMESTIC TOURISM 2627 1.5 ECONOMIC POTENTIAL HERITAGE / RELIGIOUS TOURISM 2728 1.5.1 SIKH TOURISM - A CASE STUDY 2930 1.5.2 BUDDHIST TOURISM - A CASE STUDY 3536 1.6 DEVELOPING TOURISM - KEY ISSUES & CHALLENGES 3738 1.6.1 CHALLENGES FACED BY TOURISM SECTOR IN PUNJAB 3738 1.6.2 CHALLENGES SPECIFIC TO HERITAGE TOURISM 3940 2 EXISTING INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS & REGULATORY FRAMEWORK FOR TOURISM SECTOR 4344 2.1 CURRENT INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS 4344 2.1.1 YOUTH AFFAIRS, SPORTS, ARCHAEOLOGY AND TOURISM -

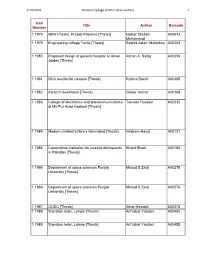

National Colege of Art Thesis List.Xlsx

4/16/2010 National College of Arts Library‐Lahore 1 Call Title Author Barcode Number 1 1975 MPA's hostel, Punjab Province [Thesis] Qaiser Ghulam A00573 Muhammad 1 1979 Engineering college Taxila [Thesis] Rashid Aslam Makhdum A00353 1 1980 Proposed design of general hospital at Aman Adnan A. Sadiq A00359 Jordan [Thesis] 1 1981 NCA residential campus [Thesis] Robina Bashir A00365 1 1982 Karachi Gymkhana [Thesis] Qaiser Ashrat A00368 1 1983 College of electronics and telecommunications Tanveer Hussain A00330 at Mir Pur Azad Kashmir [Thesis] 1 1984 Modern children's library Islamabad [Thesis] Nadeem Hayat A00121 1 1985 Correctional institution for juvenile delinquents Khalid Bhatti A00180 in Paksitan [Thesis] 1 1986 Department of space sciences Punjab Masud S Zaidi A00275 University [Thesis] 1 1986 Department of space sciences Punjab Masud S Zaidi A00276 University [Thesis] 1 1987 OGDC [Thesis] Athar Hussain A00375 1 1988 Sheraton hotel, Lahore [Thesis] Arif Iqbal Yazdani A00454 1 1988 Sheraton hotel, Lahore [Thesis] Arif Iqbal Yazdani A00455 4/16/2010 National College of Arts Library‐Lahore 2 1 1989 Engineering college Multan [Thesis] Razi-ud-Din A00398 1 1990 Islamabad hospital [Thesis] Nasir Iqbal A00480 1 1990 Islamabad hospital [Thesis] Nasir Iqbal A00492 1 1992 International Islamic University Islamabad Muhammad Javed A00584 [Thesis] 1 1994 Islamabad railway terminal: Golra junction Farah Farooq A00608 [Thesis] 1 1995 Community Facilities for Real People: Filling Ayla Musharraf A00619 Doxiadus Blanks [Thesis] 1 1995 Community Facilities -

Islamabad, Page 1 of 2

Things to Do in Islamabad, page 1 of 2 Things to Do in Islamabad Islamabad is a charming city where lush green hill backdrops and mild warm weather set it apart from other big cities in the region. It is a city, not for the night owls and party animals, but for the aesthetically inclined and to those drawn to the glory of nature. Islamabad’s relative infancy as a major metropolis is reflected in the city’s architecture, which is modern – the influence of its first urban planner Constantinos A. Doxiadis is pretty evident – yet distinctly Islamic in appearance. Faisal Mosque E-7, Islamabad, ICT, Pakistan The Faisal Mosque (also known as Shah Faisal Masjid) is the largest mosque in Pakistan, located in the national capital city of Islamabad. Completed in 1986, it was designed by Turkish architect Vedat Dalokay to be shaped like a desert Bedouin’s tent. It functions as the national mosque of Pakistan. Height: 295' (90 m) Architect: Vedat Dalokay Margalla Hills The Margalla Hills—also called Margalla Mountain Range are also a part of lesser Himalayas located north of Islamabad. Margalla Range has an area of 12,605 hectares.The hills are a part of Murree hills. It is a range with many valleys as well as high mountains. The hill range nestles between an elevation of 685 meters at the western end and 1,604 meters on its east with average height of 1000 meters. Its highest peak is Tilla Charouni.The range gets snowfall in winters. Instituted in 1980, the Margalla Hills National Park comprises the Margalla Range (12605 hectares) the Rawal Lake, and Shakarparian Sports and Cultural complex. -

Pakistan's Progress

39 Pakistan's Progress By Guy Mountfort In the short space of twelve months Pakistan has laid wide-ranging plans for conserving her wildlife, hitherto completely neglected. On the recommenda- tion of two World Wildlife Fund expeditions, led by Guy Mountfort, an international WWF trustee, two national parks and several reserves are being created which should give Pakistan a last chance to save the tiger, the snow leopard and several other seriously threatened mammals and birds. NTIL very recently wildlife conservation in Pakistan was non- U existent; today the situation is extremely encouraging. Under the direction of President Ayub Khan, most of the recommendations in the report of the 1967 World Wildlife Fund expedition have already been implemented, and a number of the proposed new wildlife reserves are now in being. A wildlife committee (in effect a Government Commission) has been set up under the distinguished chairmanship of Mr. M. M. Ahmad, Deputy Chairman of the Central Government Planning Commission, to create a permanent administrative framework for the conservation and management of wildlife and habitats, and two sub-committees are studying technical, educational, legal and administrative requirements. After submitting detailed reports and recommendations to the President in the spring of 1970, the committee will be replaced by a permanent wildlife advisory body to co-ordinate future planning. Responsibility for the management of wildlife resources has been given to the Department of Forests. Forest Officers are to be given special train- ing in wildlife ecology and management, and the first trainees have just completed courses in the United States. Meanwhile, a post-graduate curriculum in wildlife management is in preparation at the Forest Institute at Peshawar, to which Major Ian Grimwood has been seconded by FAO. -

Superfast Fibre Connectivity for Houses in Qatar

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 12 Hyderabad edge out Bangalore INDEX DOW JONES QE NYMEX QATAR 2 – 8, 28 COMMENT 26, 27 REGION 9, 10 BUSINESS 1 – 8, 13 – 16 for maiden 17,849.00 9,675.66 49.33 ARAB WORLD 10, 11 CLASSIFIED 9 – 13 Qatar LNG ‘well set to +32.00 -40.82 -0.15 INTERNATIONAL 12 – 25 SPORTS 1 – 12 +0.18% -0.42% -0.30% compete at lower prices’ IPL title Latest Figures published in QATAR since 1978 MONDAY Vol. XXXVII No. 10104 May 30, 2016 Sha’baan 23, 1437 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals New govt services centre opens Superfast fi bre Gulf Times goes from connectivity for strength to strength houses in Qatar By Darwish S Ahmed The new fibre connection their current fi bre speeds at ooredoo. Editor-in-Chief allows customers to download a qa/portal/OoredooQatar/fi bre-faq. 30-minute, 4K-quality movie in Al-Sayed also announced yester- three minutes and a two-hour, HD day Ooredoo’s “Platinum HomeZone” hen two people movie in two minutes service, which provides comprehen- meet, the better in- sive Wi-Fi coverage for large villas and Wformed person will By Peter Alagos mansions. prevail. Business Reporter “By providing additional Internet There lies the importance of points for customers with large houses newspapers in equipping people Ooredoo Qatar CEO Waleed al-Sayed or estates, Ooredoo ensures that Wi-Fi to succeed in today’s competi- A new government services centre has been opened at Mesaimeer to provide oredoo’s newly-launched introduces the country’s first 1Gbps connectivity is strong and consistent tion-driven world. -

50,000 Visitors Likely in New Cruise Season

www.thepeninsulaqatar.com BUSINESSB | 17 SPORT | 24 BP pursues new FIFA chief projects despite wants 2 more $1.4bn loss in Q2 Africa slots WEDNESDAY 27 JULY 2016 • 22 SHAWWAL 1437 ¿(?<E=5ŹŸ¿!E=25BŽſžŷ 2 $9I1<C D85@5>9>CE<1A1D1B º@5>9>CE<1A1D1B º@5>9>CE<1űA1D1B Emir arrives in Colombia Emir congratulates 50,000 visitors President Yameen of Maldives likely in new DOHA: Emir H H Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani yesterday sent a cable of congratulations to Maldives President Abdulla Yameen on his country’s Inde- cruise season pendence Day. Deputy Emir H H Sheikh Abdullah bin Hamad Al Thani also sent a congratulatory cable dock at Hamad Port until the rede- to President Yameen. velopment is complete. Prime Minister and Interior A three-fold increase “The surge in tourists arriving at Minister H E Sheikh Abdullah bin in the number Qatar’s shores offers great oppor- Nasser bin Khalifa Al Thani sent a tunity for the tourism industry in similar cable to President Yameen, of ships and an the country. reports QNA. increase of over “Working hand-in-hand with 1,000 percent in the our partners, we will ensure all our efforts, whether related to infra- 137 Qatar Airways expected number structure, visa processes or tour of passengers from operations, are well coordinated flights to Saudi for an optimal tourist experience,” 2015-16 season. he said. Representatives from across the from September 1 cruise industry value chain have Emir H H Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani yesterday arrived in Colombia on a three-day official visit.