Lecture Notes, CSE 232, Fall 2014 Semester

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RISC-V Bitmanip Extension Document Version 0.90

RISC-V Bitmanip Extension Document Version 0.90 Editor: Clifford Wolf Symbiotic GmbH [email protected] June 10, 2019 Contributors to all versions of the spec in alphabetical order (please contact editors to suggest corrections): Jacob Bachmeyer, Allen Baum, Alex Bradbury, Steven Braeger, Rogier Brussee, Michael Clark, Ken Dockser, Paul Donahue, Dennis Ferguson, Fabian Giesen, John Hauser, Robert Henry, Bruce Hoult, Po-wei Huang, Rex McCrary, Lee Moore, Jiˇr´ıMoravec, Samuel Neves, Markus Oberhumer, Nils Pipenbrinck, Xue Saw, Tommy Thorn, Andrew Waterman, Thomas Wicki, and Clifford Wolf. This document is released under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 ISA Extension Proposal Design Criteria . .1 1.2 B Extension Adoption Strategy . .2 1.3 Next steps . .2 2 RISC-V Bitmanip Extension 3 2.1 Basic bit manipulation instructions . .4 2.1.1 Count Leading/Trailing Zeros (clz, ctz)....................4 2.1.2 Count Bits Set (pcnt)...............................5 2.1.3 Logic-with-negate (andn, orn, xnor).......................5 2.1.4 Pack two XLEN/2 words in one register (pack).................6 2.1.5 Min/max instructions (min, max, minu, maxu)................7 2.1.6 Single-bit instructions (sbset, sbclr, sbinv, sbext)............8 2.1.7 Shift Ones (Left/Right) (slo, sloi, sro, sroi)...............9 2.2 Bit permutation instructions . 10 2.2.1 Rotate (Left/Right) (rol, ror, rori)..................... 10 2.2.2 Generalized Reverse (grev, grevi)....................... 11 2.2.3 Generalized Shuffleshfl ( , unshfl, shfli, unshfli).............. 14 2.3 Bit Extract/Deposit (bext, bdep)............................ 22 2.4 Carry-less multiply (clmul, clmulh, clmulr).................... -

Computer Architectures an Overview

Computer Architectures An Overview PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Sat, 25 Feb 2012 22:35:32 UTC Contents Articles Microarchitecture 1 x86 7 PowerPC 23 IBM POWER 33 MIPS architecture 39 SPARC 57 ARM architecture 65 DEC Alpha 80 AlphaStation 92 AlphaServer 95 Very long instruction word 103 Instruction-level parallelism 107 Explicitly parallel instruction computing 108 References Article Sources and Contributors 111 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 113 Article Licenses License 114 Microarchitecture 1 Microarchitecture In computer engineering, microarchitecture (sometimes abbreviated to µarch or uarch), also called computer organization, is the way a given instruction set architecture (ISA) is implemented on a processor. A given ISA may be implemented with different microarchitectures.[1] Implementations might vary due to different goals of a given design or due to shifts in technology.[2] Computer architecture is the combination of microarchitecture and instruction set design. Relation to instruction set architecture The ISA is roughly the same as the programming model of a processor as seen by an assembly language programmer or compiler writer. The ISA includes the execution model, processor registers, address and data formats among other things. The Intel Core microarchitecture microarchitecture includes the constituent parts of the processor and how these interconnect and interoperate to implement the ISA. The microarchitecture of a machine is usually represented as (more or less detailed) diagrams that describe the interconnections of the various microarchitectural elements of the machine, which may be everything from single gates and registers, to complete arithmetic logic units (ALU)s and even larger elements. -

Avoiding Decimal Errors—November 2006

MEDICATION SAFETY Avoiding Decimal Errors umbers containing decimal points on computer generated labels. A newly admitted hospital are a major source of error and when patient told her physician that she took phenobarbital 400 misplaced, can lead to misinterpreta- mg three times daily. Subsequently, the physician wrote an tion of prescriptions. Decimal points order for the drug in the dose relayed by the patient. A nurse can be easily overlooked, especially saw the prescription vial and verified that this was the correct on prescriptions that have been faxed, dose. However, prior to dispensing, a hospital pharmacist prepared on lined order sheets or prescription investigated the unusually high dose. When he checked the Npads, or written or typed on carbon and no-car- prescription vial, he found that it was labeled as “PHENO- bon-required (NCR) forms. If a decimal point is BARBITAL 32.400MG TABLET” (see graphic). missed, an overdose may occur. The importance To avoid misinterpretations due to decimal point place- of proper decimal point placement and promi- ment, health care practitioners should consider the following: nence cannot be overstated. • Always include a leading zero for dosage strengths or A decimal point should always be preceded concentrations less than one. by a whole number and never be left “naked.” • Never follow a whole number with a decimal point and a Decimal expressions of numbers less than one zero or multiple zeroes (trailing zero). should always be preceded by a zero (0) to en- • Eliminate dangerous decimal dose expressions from hance the visibility of the decimal. For example, pharmacy and prescriber electronic order entry screens, computer-generated labels, and preprinted prescriptions. -

Safe Prescribing

Special issue PRESCRIBING THE ROLE OF SAFE PRESCRIBING IN THE PREVENTION OF MEDICATION ERRORS edications are the most common cause order is written, flag the patient’s chart and place it in the of adverse events in hospitalized rack by the clerical associate to ensure that the nurse and M patients.1,2 Adverse drug events (ADEs) the pharmacist are aware of the order. This process is occur during 6.5% of hospital admissions and 1% essential because the omission of medication of patients suffer disabling injuries as a result of an administration, usually first time doses, is the most ADE.1,2,3 Common causes of medication errors are frequently reported medication error type at Shands listed in Table 1.4 Because adverse Jacksonville. reactions to medications can be Obviously, no one group of serious or fatal, it is extremely " Preventing medication healthcare professionals is responsible for important that drug allergies and errors must be a multi- all errors. Therefore, preventing the reactions are documented. medication errors must be a multi- Additionally, medications can be disciplinary effort." disciplinary effort. For any further easily confused as a result of look- questions, please contact your liaison alike or sound-alike names and pharmacist or the Drug Information abbreviations (e.g., Toradol and tramadol, O.D. Service at 244-4185. can be interpreted as once daily or right eye, and (Continued on page 2) AZT could represent azathioprine or zidovudine). It is important that everyone utilize strategies to Table 1. Common Causes of Medication Errors decrease medication errors. Several tips for safe prescribing of medications are reviewed in Table 2 and should be incorporated into daily practice.4 • Ambiguous strength designation When writing orders for patients in the • Look-alike or sound-alike names or use of hospital, the same tips are useful. -

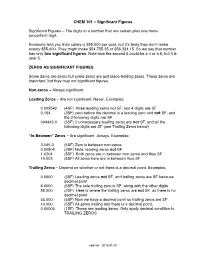

Significant Figures and Rounding

CHEM 101 – Significant Figures Significant Figures – The digits in a number that are certain plus one more (uncertain) digit. Someone tells you their salary is $55,000 per year, but it’s likely they don’t make exacty $55,000. They might make $54,755.35 or $56,324.15. So we say that number has only two significant figures. Note how the second 5 could be a 4 or a 6, but it is near 5. ZEROS AS SIGNIFICANT FIGURES Some zeros are zeros but some zeros are just place-holding zeros. These zeros are important, but they may not significant figures. Non-zeros – Always significant. Leading Zeros – Are not significant. Never. Examples: 0.005542 (4SF) three leading zeros not SF, last 4 digits are SF 0.154 (3SF) zero before the decimal is a leading zero and not SF, and the 3 following digits are SF 004445.0 (5SF) 2 unnecessary leading zeros are not SF, and all the following digits are SF (see Trailing Zeros below) “In-Between” Zeros – Are significant. Always. Examples: 3,045.3 (5SF) Zero is between non-zeros 0.00504 (3SF) Note: leading zeros not SF 1.0204 (5SF) Both zeros are in between non-zeros and thus SF 10.003 (5SF) All zeros here are in between thus SF Trailing Zeros – Depend on whether or not there is a decimal point. Examples: 0.0500 (3SF) Leading zeros not SF, and trailing zeros are SF because decimal point 6.0050 (5SF) The sole trailing zero is SF, along with the other digits 55,000 (2SF) Here is where the trailing zeros are not SF, as there is no decimal point. -

Math 124 First Midterm Examination October1 1, 2010 NAME (Please

Math 124 First Midterm Examination October1 1, 2010 NAME (Please print) Page Points Score 2 20 3 20 4 20 5 20 6 20 Total 100 Instructions: 1. Do all computations on the examination paper. You may use the backs of the pages if necessary. 2. Put answers inside the boxes. 3. Please signify your adherence to the honor code: I, , have neither given nor received aid in completion of this examination. 1 (20 Points) Score 1. (6 points) How many numbers between 1 and 10,000 have exactly one digit equal to 5? Take any number from 0 to 999 not containing 5 ( 93 numbers ) and insert 5 in one of 4 positions. Alternatively, the number has either 1, 2, 3 or 4 digits. If one digit, there is one choice. If two digits, either the last digit is 5 and the first is neither 0 or 5, or the last digit is not 5 and the first is 5; so there are 8 + 9 = 17 choices. If three digits, either the last digit is 5 and the middle is not 5 and the first is not 0 or 5, or the middle digit is 5 and ...; there are 8×9+8×9+9×9 = 225 choices. If four digits, there are 8 × 9 × 9 + 8 × 9 × 9 + 8 × 9 × 9 + 9 × 9 × 9 = 2673 choices. answer = 2916 2. (7 points) What is the number of ways to order the 26 letters of the alphabet so that no two of the vowels a, e, i, o and u occur consecutively? (Hint: order the consonants, then place the vowels.) There are 21! ways to order the consonants. -

Lesson F2.4 – Decimals Ii

LESSON F2.4 – DECIMALS II LESSON F2.4 DECIMALS II 203 204 TOPIC F2 PROPORTIONAL REASONING I Overview You have already studied decimal notation as well as how to convert a decimal number to a fraction and a fraction to a decimal number. In this lesson, you will learn how to add, subtract, multiply, and divide decimal numbers. You will also learn how to solve some equations that contain decimal numbers. Before you begin, you may find it helpful to review the following mathematical ideas that will be used in this lesson. To help you review, you may want to work out each example. Review 1 Adding whole numbers 3675 + 193 + 2781 = ? Answer: 6649 Review 2 Subtracting whole numbers 520 – 173 = ? Answer: 347 Review 3 Multiplying whole numbers 381 ϫ 67 = ? Answer: 25,527 Review 4 Dividing whole numbers 4158 Ϭ 62 = ? Answer: 67 remainder 4 Review 5 Multiplying or dividing a whole number by a power of 10 a. 87 ϫ 100 = ? Answer: 8700 b. 2300 Ϭ 100 = ? Answer: 23 Review 6 Determining the value of a digit in a decimal number What is the value of the 5 in the decimal number 3.524? 5 Answer: 0.5 or ᎏ 10 LESSON F2.4 DECIMALS II OVERVIEW 205 Explain In Concept 1: Adding and CONCEPT 1: ADDING AND SUBTRACTING Subtracting, you will find a section on each of the following: Adding Decimal Numbers • Adding Decimal Numbers To add decimal numbers: • Line up the decimal points. • Subtracting Decimal • Add the digits in each column, as you would add whole numbers. -

Lesson 1: the DECIMAL SYSTEM

Lesson 1: THE DECIMAL SYSTEM FACT 1: The word DECIMAL comes from a Latin word, which means "ten.” The Decimal system uses the following ten digits to write a number: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9. FACT 2: Each time we move one place to the left in a number, the place value increases by a factor of TEN. This can go on forever. 10 ONES become 1 TEN 10 TENS become 1 HUNDRED 10 HUNDREDS become 1 THOUSAND, and so on. FACT 3: Each time we move one place to the right in a number, the place value decreases by a factor of TEN. We stop at ONES in whole numbers. FACT 4: But the place values can continue to decrease forever by factor of TEN to the right of ONES as, TENTHS, HUNDREDTHS, THOUSANDTHS, etc. These place values can be used to express fractions. FACT 5: A DECIMAL POINT is used to separate the whole number portion from the fraction portion in a decimal number. The decimal point appears to the right of the ONES. FACT 6: Missing whole number or fraction portion may expressed by a zero. 25 may be written as 25.0; .283 may be written as 0.283 1. Indicate the place value of the underlined digit. (a) 1.5 (d) 365.742 (g) 0.007 (b) 37.2 (e) 36.5742 (h) 0.005 (c) 3.72 (f) 3657.42 (i) 5800.0 Answer: (a) tenth (b) tenth (c) tenth (d) thousandth (e) ten thousandth (f) hundredth (g) thousandth (h) hundredth (i) one 2. -

Math Milestone # B6

MATH MILESTONE # B6 DECIMAL NUMBERS The word, milestone, means “a point at which a significant change occurs.” A Math Milestone refers to a significant point in the understanding of mathematics. To reach this milestone one should be able to express and manipulate whole numbers and fractions in decimal notation. Index Page Diagnostic Test..........................................................................................2 B6.1 Decimal System ........................................................................................ 3 B6.2 Decimal Number........................................................................................ 4 B6.3 Decimal Fraction....................................................................................... 6 B6.4 Addition & Subtraction .............................................................................. 9 B6.5 Multiplication & Division.......................................................................... 10 B6.6 Periodic or Repeating Decimals ................................................................. 14 Summary................................................................................................. 17 Diagnostic Test again ............................................................................... 18 Glossary.................................................................................................. 19 Please consult the Glossary supplied with this Milestone for mathematical terms. Consult a regular dictionary at www.dictionary.com for general English -

Solving Constraints on the Intermediate Result of Decimal Floating-Point Operations

Solving Constraints on the Intermediate Result of Decimal Floating-Point Operations Merav Aharoni, Ron Maharik, Abraham Ziv IBM Research Lab in Haifa email: [email protected] Abstract hard to understand and debug; therefore decimal arithmetic is supported through software on most machines. Recently, The draft revision of the IEEE Standard for Floating- there is renewed interest in usage of decimal FP implemen- Point Arithmetic (IEEE P754) includes a definition for dec- tations both in software [5], [7] and hardware [8], [10]. imal floating-point (FP) in addition to the widely used bi- Verification of binary FP hardware is known to be an in- nary FP specification. tricate problem. Both formal methods and simulation meth- The decimal standard raises new concerns with regard ods have been developed to deal with this challenge. Veri- to the verification of hardware- and software-based designs. fication by simulation cannot cover the entire FP domain, The verification process normally emphasizes intricate cor- which is huge and involves many corner cases. For this ner cases and uncommon events. The decimal format intro- purpose, coverage models are developed [17], that define duces several new classes of such events in addition to those interesting cases for verification purposes. A coverage case characteristic of binary FP. is said to be covered if we have at least one test that hits Our work addresses the following problem: Given a dec- this case. Coverage cases can be defined on different levels: imal floating-point operation, a constraint on the interme- they can be defined in English, in terms of the implementa- diate result, and a constraint on the representation selected tion signals, or in some formal or mathematical expression for the result, find random inputs for the operation that yield language. -

Official "Do Not Use" List of Abbreviations

Official “Do Not Use” List . This list is part of the Information Management standards . Does not apply to preprogrammed health information technology systems (i.e. electronic medical records or CPOE systems), but remains under consideration for the future Organizations contemplating introduction or upgrade of such systems should strive to eliminate the use of dangerous abbreviations, acronyms, symbols and For more information dose designations from the software. • Complete the Standards Official “Do Not Use” List1 Online Question Do Not Use Potential Problem Use Instead Submission Form. U, u (unit) Mistaken for “0” Write "unit" • (zero), the number “4” Contact the Standards (four) or “cc” Interpretation Group at IU (International Mistaken for IV Write "International 630-792-5900. Unit) (intravenous) or the Unit" number 10 (ten) Q.D., QD, q.d., qd Mistaken for each Write "daily" (daily) other Q.O.D., QOD, q.o.d, Period after the Q Write "every other qod mistaken for "I" and day" (every other day) the "O" mistaken for "I Trailing zero (X.0 Decimal point is Write X mg mg)* missed Write 0.X mg Lack of leading zero (.X mg) MS Can mean morphine Write "morphine sulfate or magnesium sulfate" sulfate Write "magnesium sulfate" MSO4 and MgSO4 Confused for one another 1Applies to all orders and all medication-related documentation that is handwritten (including free-text computer entry) or on pre-printed forms. *Exception: A “trailing zero” may be used only where required to demonstrate the level of precision of the value being reported, such as for laboratory results, imaging studies that report size of lesions, or catheter/tube sizes. -

NCPDP Recommendations and Guidance for Standardizing the Dosing Designations on Prescription Container Labels of Oral Liquid Medications Version 1.0 March 2014

National Council for Prescription Drug Programs White Paper NCPDP Recommendations and Guidance for Standardizing the Dosing Designations on Prescription Container Labels of Oral Liquid Medications Version 1.0 March 2014 This paper provides the healthcare industry, in particular the pharmacy sector, with historical and background information on the patient risks associated with the dosing of liquid medications and recommendations to mitigate those risks through best practices in prescription orders, prescription labeling and the provision of dosing devices. NCPDP Recommendations and Guidance for Standardizing the Dosing Designations on Prescription Container Labels of Oral Liquid Medications Version 1.Ø NCPDP recognizes the confidentiality of certain information exchanged electronically through the use of its standards. Users should be familiar with the federal, state, and local laws, regulations and codes requiring confidentiality of this information and should utilize the standards accordingly. NOTICE: In addition, this NCPDP Standard contains certain data fields and elements that may be completed by users with the proprietary information of third parties. The use and distribution of third parties' proprietary information without such third parties' consent, or the execution of a license or other agreement with such third party, could subject the user to numerous legal claims. All users are encouraged to contact such third parties to determine whether such information is proprietary and if necessary, to consult with legal counsel to make arrangements for the use and distribution of such proprietary information. Published by: National Council for Prescription Drug Programs Publication History: Version 1.Ø Copyright 2Ø14 All rights reserved. Permission is hereby granted to any organization to copy and distribute this material as long as the copies are not sold.