Changes in Geographic Ranges in the Avifauna Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poland Trip Report May - June 2018

POLAND TRIP REPORT MAY - JUNE 2018 By Andy Walker We enjoyed excellent views of Alpine Accentor during the tour. www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | T R I P R E P O R T Poland: May - June 2018 This one-week customized Poland tour commenced in Krakow on the 28th of May 2018 and concluded back there on the 4th of June 2018. The tour visited the bird-rich fishpond area around Zator to the southwest of Krakow before venturing south to the mountains along the Poland and Slovakia border. The tour connected with many exciting birds and yielded a long list of European birding highlights, such as Black-necked and Great Crested Grebes, Red-crested Pochard, Garganey, Black and White Storks, Eurasian and Little Bitterns, Black-crowned Night Heron, Golden Eagle, Western Marsh and Montagu’s Harriers, European Honey Buzzard, Red Kite, Corn Crake, Water Rail, Caspian Gull, Little, Black, and Whiskered Terns, European Turtle Dove, Common Cuckoo, Lesser Spotted, Middle Spotted, Great Spotted, Black, European Green, and Syrian Woodpeckers, Eurasian Hobby, Peregrine Falcon, Red-backed and Great Grey Shrikes, Eurasian Golden Oriole, Eurasian Jay, Alpine Accentor, Water Pipit, Common Firecrest, European Crested Tit, Eurasian Penduline Tit, Savi’s, Marsh, Icterine, and River Warblers, Bearded Reedling, White-throated Dipper, Ring Ouzel, Fieldfare, Collared Flycatcher, Black and Common Redstarts, Whinchat, Western Yellow (Blue-headed) Wagtail, Hawfinch, Common Rosefinch, Red Crossbill, European Serin, and Ortolan Bunting. A total of 136 bird species were seen (plus 8 species heard only), along with an impressive list of other animals, including Common Fire Salamander, Adder, Northern Chamois, Eurasian Beaver, and Brown Bear. -

Spring Weights of Some Palaearctic Passer- Ines in Ethiopia and Kenya: Evidence for Important Migration Staging Areas in Eastern Ethiopia

Scopus 33: 45–52, January 2014 Spring weights of some Palaearctic passer- ines in Ethiopia and Kenya: evidence for important migration staging areas in eastern Ethiopia David Pearson, Herbert Biebach, Gerhard Nikolaus and Elizabeth Yohannes Summary Palaearctic migrants were trapped in late April and early May at a passage site near Jijiga in eastern Ethiopia. Willow Warblers Phylloscopus trochilus and Spotted Flycatchers Muscicapa striata were predominant, while Red-backed Shrikes Lanius collurio, Sedge Warblers Acrocephalus schoenobaenus, Reed Warblers A. scirpaceus, Garden Warblers Sylvia borin and Common Whitethroats S. communis also featured prominently. Weights were high in all species, and over 70% of the birds caught were extremely fat. Spring weights and fat scores at Jijiga were compared with those found in the same species in Kenya, and the difference was striking. In Kenya, most species had mean spring weights 10–20% above lean weight; at Jijiga, species’ mean weights ranged from 30% to 55% above lean weight. Whereas the reserves of most migrants departing from Kenya would have supported flights only as far as Ethiopia, the fat loads of birds at Jijiga indicated a potential for crossing Arabia with little need to feed. This suggests important staging and fattening grounds between these two areas, perhaps in the Acacia–Commiphora bushlands drained by the upper Juba and Shebelle rivers and their tributaries. Introduction Each year hundreds of millions of migrant passerines must set off from the Horn of Africa in April and early May on a crossing of the Arabian Peninsula (Moreau 1972). These are bound ultimately for Palaearctic breeding grounds distributed from Western Europe to Siberia and central Asia. -

Prunella Mod-Sylvia Sarda.P65 225 19/10/2004, 17:17

Birds in Europe – Warblers Country Breeding pop. size (pairs) Year(s) Trend Mag.% References Hippolais olivetorum Albania (1,000 – 3,000) 02 (0) (0–19) OLIVE-TREE WARBLER Bulgaria 500 – 900 96–02 + 0–9 Croatia (500 – 750) 02 (–) (0–19) 70 Non-SPECE (1994: 2) Status (Secure) Greece (3,000 – 5,000) 95–00 (–) (0–19) Criteria — Macedonia (500 – 3,000) 90–00 (0) (0–19) Serbia & MN 5 – 10 95–02 + N 1,141,155,227 European IUCN Red List Category — Turkey (5,000 – 10,000) 01 (0) (0–19) Criteria — Total (approx.) 11,000 – 23,000 Overall trend Stable Global IUCN Red List Category — Breeding range >250,000 km2 Gen. length. <3.3 % Global pop. >95 Criteria — Hippolais olivetorum is a summer visitor to south-eastern Europe, which constitutes >95% of its global breeding range. Its European breeding population is relatively small (<23,000 pairs), but was stable between 1970–1990. Despite declines in Greece and Croatia during 1990–2000, the species was stable or increased elsewhere within its European range, and probably remained stable overall. Although it was previously classified as Rare, the species’s European breeding population is now known to exceed 10,000 pairs, and consequently it is provisionally evaluated as Secure. No. of pairs ≤ 7 ≤ 1,800 ≤ 3,900 ≤ 7,100 Present Extinct Hippolais olivetorum 2000 population 96 4 1990 population 5 95 Data quality (%) – Hippolais olivetorum unknown poor medium good 1990–2000 trend 96 4 1970–1990 trend 43 57 Country Breeding pop. size (pairs) Year(s) Trend Mag.% References Hippolais icterina Austria (10,000 – 20,000) 98–02 (0) (0–19) ICTERINE WARBLER Azerbaijan (1,000 – 10,000) 96–00 (0) (0–19) Belarus 100,000 – 180,000 97–02 0 0–19 Non-SPECE (1994: 4) Status (Secure) Belgium 3,500 – 7,000 01–02 – 0–19 1 Criteria — Bosnia & HG Present 85–89 ? – Bulgaria 150 – 300 96–02 (F) (20–29) European IUCN Red List Category — Croatia (50 – 75) 02 (–) (>80) 70 Criteria — Czech Rep. -

Rejection Behavior by Common Cuckoo Hosts Towards Artificial Brood Parasite Eggs

REJECTION BEHAVIOR BY COMMON CUCKOO HOSTS TOWARDS ARTIFICIAL BROOD PARASITE EGGS ARNE MOKSNES, EIVIN ROSKAFT, AND ANDERS T. BRAA Departmentof Zoology,University of Trondheim,N-7055 Dragvoll,Norway ABSTRACT.--Westudied the rejectionbehavior shown by differentNorwegian cuckoo hosts towardsartificial CommonCuckoo (Cuculus canorus) eggs. The hostswith the largestbills were graspejectors, those with medium-sizedbills were mostlypuncture ejectors, while those with the smallestbills generally desertedtheir nestswhen parasitizedexperimentally with an artificial egg. There were a few exceptionsto this general rule. Becausethe Common Cuckooand Brown-headedCowbird (Molothrus ater) lay eggsthat aresimilar in shape,volume, and eggshellthickness, and they parasitizenests of similarly sizedhost species,we support the punctureresistance hypothesis proposed to explain the adaptivevalue (or evolution)of strengthin cowbirdeggs. The primary assumptionand predictionof this hypothesisare that somehosts have bills too small to graspparasitic eggs and thereforemust puncture-eject them,and that smallerhosts do notadopt ejection behavior because of the heavycost involved in puncture-ejectingthe thick-shelledparasitic egg. We comparedour resultswith thosefor North AmericanBrown-headed Cowbird hosts and we found a significantlyhigher propor- tion of rejectersamong CommonCuckoo hosts with graspindices (i.e. bill length x bill breadth)of <200 mm2. Cuckoo hosts ejected parasitic eggs rather than acceptthem as cowbird hostsdid. Amongthe CommonCuckoo hosts, the costof acceptinga parasiticegg probably alwaysexceeds that of rejectionbecause cuckoo nestlings typically eject all hosteggs or nestlingsshortly after they hatch.Received 25 February1990, accepted 23 October1990. THEEGGS of many brood parasiteshave thick- nestseither by grasping the eggs or by punc- er shells than the eggs of other bird speciesof turing the eggs before removal. Rohwer and similar size (Lack 1968,Spaw and Rohwer 1987). -

HUNGARY May2017

TRIP REPORT HUNGARY - WILDLIFE OF THE KISKUNSAG Thursday 18th - Tuesday 23rd May 2017 TOUR PARTICIPANTS ANDREW DUCAT SUE SMALL PENNY GRACE DAVID SMITH BRIAN JAMES RICHARD STANLEY HOWARD MANNERS JOHN WILLIAMS JUDY ROSS DRIVER ZOLI TOUR LEADERS GÁBOR ORBÁN, ANDREA KATONA & STEVE GRIMWADE Hawfinch by Andrew Ducat Thursday 18th May 2017 Our group met at Gatwick for a mid-morning flight to Budapest which took off a little later than scheduled, but in only just over two hours we found ourselves in a warm Budapest with temperatures around 25 degrees. After picking up luggage we met up with Andrea, one of our guides for the tour who took us to our bus which was driven by Zoli (who had driven on our tour in 2013). It didn’t long to load up and we were soon on our way to a small village where we were shown a traditional church built in the 13th century. Thatched cottages looked quaint and soon we heard the drumming of a male SYRIAN WOODPECKER. We spotted it coming in and out of a nest hole with the male and female taking turns to feed the young. A cracking male BLACK REDSTART sat atop a weather vane allowing good photographic opportunities whilst common species were seen such as EURASIAN COLLARED DOVE, COMMON STARLING and a distant singing EUROPEAN SERIN. We were then off towards our base but along the way stopped off at a woodland for a brief stroll. EUROPEAN NUTHATCH and SHORT-TOED TREECREEPERS were seen plus SPOTTED FLYCATCHERS, whilst the songs of COMMON CHAFFINCH, SONG THRUSH and EUROPEAN ROBIN emanated from the woodland. -

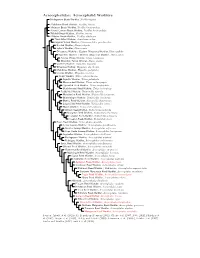

Acrocephalidae Species Tree

Acrocephalidae: Acrocephalid Warblers Madagascan Brush-Warbler, Nesillas typica ?Subdesert Brush-Warbler, Nesillas lantzii ?Anjouan Brush-Warbler, Nesillas longicaudata ?Grand Comoro Brush-Warbler, Nesillas brevicaudata ?Moheli Brush-Warbler, Nesillas mariae ?Aldabra Brush-Warbler, Nesillas aldabrana Thick-billed Warbler, Arundinax aedon Papyrus Yellow Warbler, Calamonastides gracilirostris Booted Warbler, Iduna caligata Sykes’s Warbler, Iduna rama Olivaceous Warbler / Eastern Olivaceous-Warbler, Iduna pallida Isabelline Warbler / Western Olivaceous-Warbler, Iduna opaca African Yellow Warbler, Iduna natalensis Mountain Yellow Warbler, Iduna similis Upcher’s Warbler, Hippolais languida Olive-tree Warbler, Hippolais olivetorum Melodious Warbler, Hippolais polyglotta Icterine Warbler, Hippolais icterina Sedge Warbler, Titiza schoenobaenus Aquatic Warbler, Titiza paludicola Moustached Warbler, Titiza melanopogon ?Speckled Reed-Warbler, Titiza sorghophila Black-browed Reed-Warbler, Titiza bistrigiceps Paddyfield Warbler, Notiocichla agricola Manchurian Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla tangorum Blunt-winged Warbler, Notiocichla concinens Blyth’s Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla dumetorum Large-billed Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla orina Marsh Warbler, Notiocichla palustris African Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla baeticata Mangrove Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla avicenniae Eurasian Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla scirpacea Caspian Reed-Warbler, Notiocichla fusca Basra Reed-Warbler, Acrocephalus griseldis Lesser Swamp-Warbler, Acrocephalus gracilirostris Greater Swamp-Warbler, Acrocephalus -

EUROPEAN BIRDS of CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, Trends and National Responsibilities

EUROPEAN BIRDS OF CONSERVATION CONCERN Populations, trends and national responsibilities COMPILED BY ANNA STANEVA AND IAN BURFIELD WITH SPONSORSHIP FROM CONTENTS Introduction 4 86 ITALY References 9 89 KOSOVO ALBANIA 10 92 LATVIA ANDORRA 14 95 LIECHTENSTEIN ARMENIA 16 97 LITHUANIA AUSTRIA 19 100 LUXEMBOURG AZERBAIJAN 22 102 MACEDONIA BELARUS 26 105 MALTA BELGIUM 29 107 MOLDOVA BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 32 110 MONTENEGRO BULGARIA 35 113 NETHERLANDS CROATIA 39 116 NORWAY CYPRUS 42 119 POLAND CZECH REPUBLIC 45 122 PORTUGAL DENMARK 48 125 ROMANIA ESTONIA 51 128 RUSSIA BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is a partnership of 48 national conservation organisations and a leader in bird conservation. Our unique local to global FAROE ISLANDS DENMARK 54 132 SERBIA approach enables us to deliver high impact and long term conservation for the beneit of nature and people. BirdLife Europe and Central Asia is one of FINLAND 56 135 SLOVAKIA the six regional secretariats that compose BirdLife International. Based in Brus- sels, it supports the European and Central Asian Partnership and is present FRANCE 60 138 SLOVENIA in 47 countries including all EU Member States. With more than 4,100 staf in Europe, two million members and tens of thousands of skilled volunteers, GEORGIA 64 141 SPAIN BirdLife Europe and Central Asia, together with its national partners, owns or manages more than 6,000 nature sites totaling 320,000 hectares. GERMANY 67 145 SWEDEN GIBRALTAR UNITED KINGDOM 71 148 SWITZERLAND GREECE 72 151 TURKEY GREENLAND DENMARK 76 155 UKRAINE HUNGARY 78 159 UNITED KINGDOM ICELAND 81 162 European population sizes and trends STICHTING BIRDLIFE EUROPE GRATEFULLY ACKNOWLEDGES FINANCIAL SUPPORT FROM THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION. -

Stopover Dynamics of 12 Passerine Migrant Species in a Small Mediterranean Island During Spring Migration

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Epsilon Open Archive Journal of Ornithology (2020) 161:793–802 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-020-01768-7 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Stopover dynamics of 12 passerine migrant species in a small Mediterranean island during spring migration Ivan Maggini1 · Marta Trez1 · Massimiliano Cardinale2 · Leonida Fusani1,3 Received: 16 September 2019 / Revised: 1 February 2020 / Accepted: 12 March 2020 / Published online: 30 March 2020 © The Author(s) 2020 Abstract Small coastal islands ofer landing opportunities for large numbers of migratory birds following long sea crossings. However, they do not always provide sufcient refueling opportunities, thus raising questions about their importance for the success of migratory journeys. Here we analyzed a large dataset collected during 3 years of captures and recaptures of 12 species on the island of Ponza, central Italy, to determine the importance of the island for refueling. Despite the very large amount of birds on the island, only a very small fraction (usually below 2%) stayed on the island for longer than 1 day. These birds had low energy stores and, in most cases, they were not able to successfully refuel on Ponza. Only two species (Subalpine Warbler and Common Chifchaf) had a positive fuel deposition rate, possibly as a result of the better suitability of the island’s habitat to these two species. We underline that the large use of the island despite the relatively low refueling opportunities may be due to other aspects that it may ofer to the birds. Possibly, birds just landed after a long sea crossing may require a short rest or sleep and can fnd opportunities to do that on the islands, reinitiating their onward fight after just a few hours. -

Field-Identification of Hippolais Warblers by D.I M

Field-identification of Hippolais warblers By D.I M. Wallace INTRODUCTION THE GENUS HIPPOLAIS is a small one of only six species. Two of these, the Icterine Warbler H. icterina and the Melodious Warbler H. polyglotta, are now proven annual vagrants to Great Britain and Ireland; another two, the Olivaceous Warbler H.pallida and the Booted Warbler H. caligata, occur here as rare stragglers; and the final pair, the Olive-tree Warbler H. olivetorum and Upcher's Warbler H. languida, might conceivably reach us in the future. All except the last breed in Europe, though the Booted Warbler does so no further west than Russia. For many years the members of this genus have been labelled difficult to identify, in much the same way as other groups where plumage pattern alone is not always sufficient for certain diagnosis. Williamson (i960) included all the species and races in the first of his systematic guides to the warblers, but the detailed information he gave was primarily intended to aid ringers with birds in the hand and, although some general comments on the genus (at times dangerously misleading if applied to individual species) were made by Alexander (1955), no descriptive treatment so far published is adequate for accuracy in field identification. I do not presume to be able to meet this need fully, but I have watched all six species on migration in Europe or the Near East (Jordan) and have more thoroughly studied three of them in both their European breeding-habitats and their African winter-quarters. In addition, I have discussed Hippolais identification with many field ornithologists and have investigated all the records published in this journal and several observatory reports over the last ten years. -

From Mediterranean to Scandinavia – Timing and Body Mass Condition In

ORNIS SVECICA 25:51–58, 2015 From Mediterranean to Scandinavia – timing and body mass condition in four long distance migrants Från Medelhavet till Skandinavien – tidsmässigt uppträdande och energireserver hos fyra långdistansflyttande tättingar CHRISTOS BARBOUTIS, LEO LARSSON, ÅSA STEINHOLTZ & THORD FRANSSON Abstract In spring, long-distance migrants are considered to adopt arrive at the Swedish study site with significantly higher a time-minimizing strategy to promote early arrival at body masses compared to when they arrive in Greece and breeding sites. The phenology of spring migration was this might indicate a preparation for arriving at breeding examined and compared between two insular stopover grounds with some overload. sites in Greece and Sweden for Icterine Warbler, Wood Warbler, Spotted Flycatcher and Collared Flycatcher. Christos Barboutis, Antikythira Bird Observatory, Hel- All of them migrate due north which means that some lenic Ornithological Society, 80 Themistokleous str, proportion of birds that pass through Greece are heading GR-10681, Athens, Greece; Natural History Museum of to Scandinavia. The Collared Flycatcher had the earli- Crete, University of Crete, PO Box 2208, 71409 Herak- est and the Icterine Warbler the latest arrival time. The lion, Crete, Greece. Email: [email protected] differences in median dates between Greece and Swe- (corresponding author) den were 3–4 weeks and the passages in Sweden were Leo Larsson & Åsa Steinholtz, Sundre Bird Observatory, generally more condensed in time. The average overall Sundre, Skoge 518, SE-623 30 Burgsvik, Sweden speed estimates were very similar and varied between Thord Fransson, Department of Environmental Research 129 and 137 km/d. In most of the species higher speed and Monitoring, Swedish Museum of Natural History, estimates were associated with years when birds arrived Box 50 007, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden late in Greece. -

Icterine Warbler

NOTES A useful field-character of the Icterine Warbler. — Icterine Warblers (Hippolais icterina) were watched at Fair Isle, and identification confirmed by trapping- and examination of the wing- formula, on 30th May and 9th September 1954. The purpose of this note is to draw attention to a useful distinguishing characteristic which is not mentioned under the heading "Field- characters" in The Handbook (vol. II, pp. 61-62) or other recent bird-identification guides. The spring specimen was bright greenish-olive above and exceedingly yellow beneath, and perhaps likely to be confused with a Wood Warbler (Phylloscopus sibilatrix) on a poor view. The autumn example trapped on 9th September, and an apparently identical bird watched for some time at close quarters on 7th and 8th, were much duller above and only very pale yellowish beneath: in indifferent light they could easily have been confused with a Garden Warbler (Sylvia borin). The best field-mark at both seasons was afforded by a light patch in the closed wing, pale golden-yellow in the spring bird and off-white in the autumn examples, which made a sharp contrast with the dark brown flight-feathers. This patch is caused by the overlapping pale fringes of the secondaries, and creates a wing-pattern which at once precludes confusion with any Sylvia or Phylloscopus species. Although this character does not appear to have been recorded, I may point out that the pale wing-patch is clearly visible in the excellent photographs of the Icterine Warbler taken by Eric Hosking and Ian M. Thomson and published antea, vol. -

Bird Migration Dear Readers

Bird migration Dear Readers, The world of birds is full of fas- begin their migration to Africa into English and published it elec- cinating stories. Perhaps one of in August to spend the winter tronically. The PDF file is to be the most impressive is the annual in central Africa. In April they distributed free of charge, and we migration of many bird species return to Germany, display their encourage you to forward the file from Europe to Africa and back. A spectacular flight in our summer to anyone you think might share Wood Warbler, for skies, again migrate our enthusiasm for bird migration example, weighing to Africa and back and might be interested in this only ten grams, and for the first time publication. (the same weight build a nest and raise as ten paperclips) young. Two years We, along with the expert board flies from Britain from fledging to the of DER FALKE, hope that we to Ghana, often first brood, without have brought the phenomenon using exactly the touching the ground of bird migration closer to you same stopover sites once – as far as we with this extra issue. If you view in Burkina Faso, to know! Wood Warblers, Barn Swallows, winter in the same Wheatears, Cuckoos or Swifts group of trees as Common Cranes. Photo: H.-J. Fünfstück. In this special issue with slightly different eyes in the the year before. of DER FALKE, „Bird future and share our enthusiasm Barn Swallows from Europe jour- migration“, we wanted to explore for bird migration, then we have ney all the way to South Africa, bird migration in all its facets and achieved our objective.