'Belgian Linguistic' Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF Viewing Archiving 300

Bull. Soc. belge Géol., Paléont., Hydrol. T. 78 fasc. 2 pp. 111-130 Bruxelles 1969 Bull. Belg. Ver. Geol., Paleont., Hydrol. V. 78 deel 2 blz. 111-130 Brussel 1969 THE TYPE-LOCALITY OF THE SANDS OF GRIMMERTINGEN AND CALCAREOUS NANNOPLANKTON FROM THE LOWER TONGRIAN E. MARTINI 1 & T. MooRKENS 2 CONTENT Summary 111 Zusammenfassung 111 Résumé 112 1. Introduction . 112 2. Historical review of some chronostratigraphical conceptions. 114 3. The Eocene-Oligocene transitional strata in Belgium 115 4. Locality details 122 5. The calcareous nannoplankton assemblages 124 6. Conclusions . 125 7. Acknowledgments . 127 8. References 127 SuMMARY. A. DUMONT (1839-1849) considered the Sands of Grimmertingen as the base of his Ton grian stage (Grimmertingen is at present a hamlet in the municipality of Vliermaal in the Eastern part of Belgium). Samples have been taken from the outcrop of the type-locality and from a new boring reaching a depth of 12,5 m, towards the base of this member. Sorne of these sa.mples from both outcrop and boring yielded fairly rich assemblages of calcareous nannoplankton of which a list is given: the assemblages belong to the Ellipsolithus subdistichus zone, the zone which was also recognised in the sand extracted from the molluscs of the type-Latdorfian (Lower Oligocene). The recent sampling of the Grimmertingen-locality also permitted to find fairly rich associations of Hystrichospheres and of planktonic and benthonic Foraminifera, which are under current study. ZusAMMENFASSUNG. A. DUMONT (1839-1849) stellte die Sande von Grimmertingen an die Basis seines ,,Tongrien" (Grimmertingen befindet sich heute im Stadtbereich von Vliermaal im ostlichen Teil von Belgien). -

Doing Business in Belgium

DOING BUSINESS IN BELGIUM CONTENTS 1 – Introduction 3 2 – Business environment 4 3 – Foreign Investment 7 4 – Setting up a Business 9 5 – Labour 17 6 – Taxation 20 7 – Accounting & reporting 29 8 – UHY Representation in Belgium 31 DOING BUSINESS IN BELGIUM 3 1 – INTRODUCTION UHY is an international organisation providing accountancy, business management and consultancy services through financial business centres in over 100 countries throughout the world. Business partners work together through the network to conduct transnational operations for clients as well as offering specialist knowledge and experience within their own national borders. Global specialists in various industry and market sectors are also available for consultation. This detailed report providing key issues and information for investors considering business operations in Belgium has been provided by the office of UHY representatives: UHY-CDP PARTNERS Square de l’Arbalète, 6, B-1170 Brussels Belgium Phone +32 2 663 11 20 Website www.cdp-partners.be Email [email protected] You are welcome to contact Chantal Bollen ([email protected]) for any inquiries you may have. A detailed firm profile for UHY’s representation in Belgium can be found in section 8. Information in the following pages has been updated so that they are effective at the date shown, but inevitably they are both general and subject to change and should be used for guidance only. For specific matters, investors are strongly advised to obtain further information and take professional advice before making any decisions. This publication is current at July 2021. We look forward to helping you doing business in Belgium DOING BUSINESS IN BELGIUM 4 2 – BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT OVERVIEW COUNTRY AND NATION Belgium is a small country (30,528 square kilometres) at the centre of the most significant industrial and urban area in Western Europe. -

Memorandum Vlaamse En Federale

MEMORANDUM VOOR VLAAMSE EN FEDERALE REGERING INLEIDING De burgemeesters van de 35 gemeenten van Halle-Vilvoorde hebben, samen met de gedeputeerden, op 25 februari 2015 het startschot gegeven aan het ‘Toekomstforum Halle-Vilvoorde’. Toekomstforum stelt zich tot doel om, zonder bevoegdheidsoverdracht, de kwaliteit van het leven voor de 620.000 inwoners van Halle-Vilvoorde te verhogen. Toekomstforum is een overleg- en coördinatieplatform voor de streek. We formuleren in dit memorandum een aantal urgente vragen voor de hogere overheden. We doen een oproep aan alle politieke partijen om de voorstellen op te nemen in hun programma met het oog op het Vlaamse en federale regeerprogramma in de volgende legislatuur. Het memorandum werd op 19 december 2018 voorgelegd aan de burgemeesters van de steden en gemeenten van Halle-Vilvoorde en door hen goedgekeurd. 1. HALLE-VILVOORDE IS EEN CENTRUMREGIO Begin 2018 hebben we het dossier ‘Centrumregio-erkenning voor Vlaamse Rand en Halle’ met geactualiseerde cijfers gepubliceerd (zie bijlage 1). De analyse van de cijfers toont zwart op wit aan dat Vilvoorde, Halle en de brede Vlaamse Rand geconfronteerd worden met (groot)stedelijke problematieken, vaak zelfs sterker dan in andere centrumsteden van Vlaanderen. Momenteel is er slechts een beperkte compensatie voor de steden Vilvoorde en Halle en voor de gemeente Dilbeek. Dat is positief, maar het is niet voldoende om de problematiek, met uitlopers over het hele grondgebied van het arrondissement, aan te pakken. Toekomstforum Halle-Vilvoorde vraagt een erkenning van Halle-Vilvoorde als centrumregio. Deze erkenning zien we als een belangrijk politiek signaal inzake de specifieke positie van Halle-Vilvoorde. De erkenning als centrumregio moet extra financiering aanreiken waarmee de lokale besturen van de brede Vlaamse rand projecten en acties kunnen opzetten die de (groot)stedelijke problematieken aanpakken. -

Koppelteken Voor Een Regio 1950 1969 1970 1989 1990 2009 2010 • Eerste Steen Gordel Van Smaragd (Westrand)

Tina Deneyer 20 jaar ‘de Rand’ Koppelteken voor een regio 1950 1969 1970 1989 1990 2009 2010 • eerste steen Gordel van Smaragd (Westrand) 1991 • verbouwde GC de Moelie 2008 • Documentatiecentrum Vlaamse Rand 1992 • oprichting Vlabinvest 1968 • cultuurraad 1971 • verkiezing 1988 • ‘betonnering’ Wezembeek-Oppem Randfederaties faciliteiten • pacificatiewet: systeem 1993 • GC de Kam rechtstreekse Wezembeek-Oppem 2007 • GC de Muse 2012 • goedkeuring verkiezing • Sint-Michielsakkoord: splitsing BHV splitsing provincie Brabant, rechtstreekse verkiezing Vlaams parlement 1954 • publicatie 1967 • ontwerp-gewestplan: 1972 • Nederlandse 1987 • nieuwe GC de Zandloper 2006 • budget taalpromotie talentelling 1947: Kulturele Raad (NKR) Kaasmarkt Wemmel • Groene Gordel 1994 • start Vlabinvest omvorming tot EVA Tina Deneyer externe tweetalig- Wemmel heid in Drogenbos, Wemmel, Kraainem en Linkebeek 1995 • provincie 20 jaar ‘de Rand’ Vlaams-Brabant 1974 • Kultuurraad Kraainem 2005 • Taskforce Vlaamse 2013 • decretale wijziging: • RINGtv • bescherming Rand jeugd en sport in de • Boesdaalhoeve nieuw deel GC de zes naar vzw ‘de Rand’ • Zandloper Zijp Lijsterbes Kraainem • eerste Gordelfestival • 1963 • taalwet en faciliteiten: Wemmel 1986 • Jazz Hoeilaart onderzoek Mens & • laatste Jazz Hoeilaart naast Drogenbos, • Socio-culturele Raad voortaan in Ruimte • decreet deugdelijk Koppelteken Kraainem, Linkebeek Linkebeek GC de Bosuil bestuur in de publieke en Wemmel ook sector Sint-Genesius-Rode en 2004 • kaaskrabber Wezembeek-Oppem 1996 • actieplan van de voor -

Participants Brochure REPUBLIC of KOREA 10 > 17 June 2017 BELGIAN ECONOMIC MISSION

BELGIAN ECONOMIC MISSION Participants Brochure REPUBLIC OF KOREA 10 > 17 June 2017 BELGIAN ECONOMIC MISSION 10 > 17 June 2017 Organised by the regional agencies for the promotion of Foreign Trade & Investment (Brussels Invest & Export, Flanders Investment & Trade (FIT), Wallonia Export-Investment Agency), FPS Foreign Affairs and the Belgian Foreign Trade Agency. Publication date: 10th May 2017 REPUBLIC OF KOREA This publication contains information on all participants who have registered before its publication date. The profiles of all participants and companies, including the ones who have registered at a later date, are however published on the website of the mission www.belgianeconomicmission.be and on the app of the mission “Belgian Economic Mission” in the App Store and Google Play. Besides this participants brochure, other publications, such as economic studies, useful information guide, etc. are also available on the above-mentioned website and app. REPUBLIC OF KOREA BELGIAN ECONOMIC MISSIONS 4 CALENDAR 2017 IVORY COAST 22 > 26 October 2017 CALENDAR 2018 ARGENTINA & URUGUAY June 2018 MOROCCO End of November 2018 (The dates are subject to change) BELGIAN ECONOMIC MISSION REPUBLIC OF KOREA Her Royal Highness Princess Astrid, Princess mothers and people lacking in education and On 20 June 2013, the Secretariat of the Ot- of Belgium, was born in Brussels on 5 June skills. tawa Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention 1962. She is the second child of King Albert announced that Princess Astrid - as Special II and Queen Paola. In late June 2009, the International Paralym- Envoy of the Convention - would be part of pic Committee (IPC) Governing Board ratified a working group tasked with promoting the After her secondary education in Brussels, the appointment of Princess Astrid as a mem- treaty at a diplomatic level in states that had Princess Astrid studied art history for a year ber of the IPC Honorary Board. -

Commercial Assistant - Career Website 7503 Flemish Brabant

Commercial Assistant - Career Website 7503 Flemish Brabant Commercial Assistant Commercial Assistant - Vilvoorde Location : Flemish Brabant Intro Would you like to become one of the unique bpost faces? Good news: even in this age of social distancing we continue to look for talent. We need you – now more than ever – to help us connect people. Thanks to the hundreds of colleagues at our cleaning service, who have provided thousands of litres of hand sanitiser and tens of thousands of facemasks, bpost is able to guarantee a covid-secure application process and working environment. Read more Read less Tasks & Responsibilities You log every phone call in our contact management system. You ensure that data is correctly logged at all times. If a customer needs documents, brochures or information, you make sure the customer receives them. You keep your knowledge up to date by following training or studying on your own. You pass on valuable input to your team leader that can help improve service. You always prioritise our strict confidentiality and fraud-fighting rules. Read more Read less Profile You have a secondary school diploma. You have at least six months’ experience in an equivalent position. You can handle customer and call processes. You have good knowledge of Dutch and basic knowledge of French. You can use Microsoft Office and other relevant applications. You are focused on customers and results, and you are good at dealing with stress. You are a team player, sociable with good listening skills. You always look at things with an analytical mind. Read more Read less Our offer At bpost you make the difference by being a good listener and having a customer-first mindset. -

GOING GLOBAL EXPORTING to BELGIUM a Guide for Clients

GOING GLOBAL EXPORTING TO BELGIUM A guide for clients #GlobalAmbition Capital Brussels Population 11.43m1 GDP per capita ¤35,3002 GDP growth (2018) 1.4%3 ANTWERPEN Unemployment rate 4 OOST-VLAANDEREN LIMBURG WEST-VLAANDEREN 5.7% VLAAMS - BRABANT Enterprise Ireland client exports (2018) BRABANT WALLON ¤467.5m HAINAUT LIEGE (Belgium & Luxemburg)5 NAMUR LUXEMBOURG 2 WHY EXPORT TO BELGIUM? Known as the heart of Europe, MANY IRISH COMPANIES ARE Belgium is a hub of international EXPORTING TO BELGIUM. WHAT’S cooperation and networking. STOPPING YOU? It is a country of three regions: Flanders, Wallonia One of the highest rates of and the Brussels-Capital Region, and has three official languages: Dutch, French and German. A Biotech R&D activity in the modern private enterprise economy, it is often EU13. Antwerp is the world’s viewed as a springboard into mainland Europe. second largest chemical Situated at the crossroads of three major cultures cluster after Heuston14. – Germanic, Roman and Anglo-Saxon - it is a good “test market” for companies looking to grow into the broader European markets by establishing a local Audiovisual services account presence or through trade. for 80% of Belgium’s Belgium has 16% of Europe’s Biotech6 industry creative service exports and and 19% of Europe’s pharmaceutical exports7. It 90% of its imports15. is incredibly successful given its modest size, by population and geography. The Belgian economy continues to grow at a modest Pharma and Life Sciences pace, mainly supported by robust growth in exports. has been a continuously It is ranked as the 11th largest export economy in the strong sector for Irish world, with a positive trade balance and its latest 16 fiscal reforms improving its attractiveness. -

Partitive Article

Book Disentangling bare nouns and nominals introduced by a partitive article IHSANE, Tabea (Ed.) Abstract The volume Disentangling Bare Nouns and Nominals Introduced by a Partitive Article, edited by Tabea Ihsane, focuses on different aspects of the distribution, semantics, and internal structure of nominal constituents with a “partitive article” in its indefinite interpretation and of potentially corresponding bare nouns. It further deals with diachronic issues, such as grammaticalization and evolution in the use of “partitive articles”. The outcome is a snapshot of current research into “partitive articles” and the way they relate to bare nouns, in a cross-linguistic perspective and on new data: the research covers noteworthy data (fieldwork data and corpora) from Standard languages - like French and Italian, but also German - to dialectal and regional varieties, including endangered ones like Francoprovençal. Reference IHSANE, Tabea (Ed.). Disentangling bare nouns and nominals introduced by a partitive article. Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2020 DOI : 10.1163/9789004437500 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:145202 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 Disentangling Bare Nouns and Nominals Introduced by a Partitive Article - 978-90-04-43750-0 Downloaded from PubFactory at 10/29/2020 05:18:23PM via Bibliotheque de Geneve, Bibliotheque de Geneve, University of Geneva and Universite de Geneve Syntax & Semantics Series Editor Keir Moulton (University of Toronto, Canada) Editorial Board Judith Aissen (University of California, Santa Cruz) – Peter Culicover (The Ohio State University) – Elisabet Engdahl (University of Gothenburg) – Janet Fodor (City University of New York) – Erhard Hinrichs (University of Tubingen) – Paul M. -

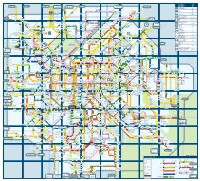

A 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 B C D E F G H I J a B C D E F G H

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 POINTS D’INTÉRÊT ARRÊT BEZIENSWAARDIGHEDEN HALTE Asse Puurs via Liezele Humbeek Mechelen Drijpikkel Puurs via Willebroek Luchthaven Malines Malderen Mechelen - Antwerpen POINT OF INTEREST STOP Dendermonde Boom via Londerzeel Kapelle-op-den-Bos Zone tarifaire MTB Tariefzone MTB Antwerpen Malines - Anvers Boom via Tisselt Verbrande Brug Anvers Stade Roi Baudouin Heysel B2 Koning Boudewijn stadion Heizel Jordaen Pellenberg Heysel Ennepetal Minnemolen Sportcomplex Kerk Vilvoorde Heldenplein Atomium B3 Vilvoorde Station 64 Heizel Vlierkens 260 47 58 Kerk Machelen 820 Machelen A 250-251 460-461 A 230-231-232 Twee Leeuwenweg Vilvoorde Heysel Blokken Brussels Expo B3 Zone tarifaire MTB Tariefzone MTB Koningin Fabiola Heizel VTM Drie Fonteinen Parkstraat Aéroport Bruxelles National Windberg Kasteel Luchthaven Brussel-Nationaal Brussels Airport B8 Zellik Station Twyeninck Witloof Beaulieu Raedemaekers Brussels National Airport Dilbeek Keebergen Kaasmarkt Robbrechts Cortenbach Kampenhout RTBF 243-820 Kerk Kortenbach Haacht Diamant D6 Hoogveld VRT Kerk Haren-Sud SAO DGHR Domaine Militaire Omnisports Haren 270-271-470 Markt Bever De Villegas Buda Haren-Zuid Omnisport Haren Basilique de Koekelberg Rijkendal Militair Hospitaal DOO DGHR Militair Domein Dobbelenberg Bossaert-Basilique Gemeenteplein Biplan Basiliek van Koekelberg E2 Guido Gezelle Vijvers Hôpital Militaire 47 Bicoque Aérodrome Bossaert-Basiliek Tweedekker Vliegveld Leuven National Basilica 820 Van Zone tarifaire MTB Louvain 240 Bloemendal Long Bonnier Beyseghem 53 57 -

Vlaamse Rand VLAAMSE RAND DOORGELICHT

Asse Beersel Dilbeek Drogenbos Grimbergen Hoeilaart Kraainem Linkebeek Machelen Meise Merchtem Overijse Sint-Genesius-Rode Sint-Pieters-Leeuw Tervuren Vilvoorde Wemmel Wezembeek-Oppem Zaventem Vlaamse Rand VLAAMSE RAND DOORGELICHT Studiedienst van de Vlaamse Regering oktober 2011 Samenstelling Diensten voor het Algemeen Regeringsbeleid Studiedienst van de Vlaamse Regering Cijferboek: Naomi Plevoets Georneth Santos Tekst: Patrick De Klerck Met medewerking van het Documentatiecentrum Vlaamse Rand Verantwoordelijke uitgever Josée Lemaître Administrateur-generaal Boudewijnlaan 30 bus 23 1000 Brussel Depotnummer D/2011/3241/185 http://www.vlaanderen.be/svr INHOUD INLEIDING ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Algemene situering .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 1. Demografie ......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Aantal inwoners neemt toe ............................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Aantal huishoudens neemt toe....................................................................................................... 5 1.3 Bevolking is relatief jong én vergrijst verder -

315 Bus Dienstrooster & Lijnroutekaart

315 bus dienstrooster & lijnkaart 315 Kraainem - Tervuren - Leefdaal - Leuven Bekijken In Websitemodus De 315 buslijn (Kraainem - Tervuren - Leefdaal - Leuven) heeft 4 routes. Op werkdagen zijn de diensturen: (1) Bertem Alsemberg: 07:50 (2) Bertem Oud Station: 12:00 (3) Leuven Station Perron 1: 05:45 - 18:45 (4) Sint- Lambrechts-Woluwe Kraainem Metro: 05:45 - 18:45 Gebruik de Moovit-app om de dichtstbijzijnde 315 bushalte te vinden en na te gaan wanneer de volgende 315 bus aankomt. Richting: Bertem Alsemberg 315 bus Dienstrooster 13 haltes Bertem Alsemberg Dienstrooster Route: BEKIJK LIJNDIENSTROOSTER maandag 07:50 dinsdag 07:50 Leuven Station Perron 10 perron 11 & 12, Leuven woensdag 07:50 Leuven J.Stasstraat donderdag 07:50 87 Bondgenotenlaan, Leuven vrijdag 07:50 Leuven Rector De Somerplein Zone B zaterdag Niet Operationeel 5 Margarethaplein, Leuven zondag Niet Operationeel Leuven Dirk Boutslaan 38 Dirk Boutslaan, Leuven Leuven De Bruul 4A Brouwersstraat, Leuven 315 bus Info Route: Bertem Alsemberg Leuven Sint-Rafaelkliniek Haltes: 13 18 Kapucijnenvoer, Leuven Ritduur: 18 min Samenvatting Lijn: Leuven Station Perron 10, Leuven Sint-Jacobsplein Leuven J.Stasstraat, Leuven Rector De Somerplein Sint-Jacobsplein, Leuven Zone B, Leuven Dirk Boutslaan, Leuven De Bruul, Leuven Sint-Rafaelkliniek, Leuven Sint-Jacobsplein, Leuven Tervuursepoort Leuven Tervuursepoort, Heverlee Egenhovenweg, 1 Herestraat, Leuven Heverlee Berg Tabor, Heverlee Sociaal Hogeschool, Heverlee Bremstraat, Bertem Alsemberg Heverlee Egenhovenweg 116 Tervuursesteenweg, -

Belgian Beer Experiences in Flanders & Brussels

Belgian Beer Experiences IN FLANDERS & BRUSSELS 1 2 INTRODUCTION The combination of a beer tradition stretching back over Interest for Belgian beer and that ‘beer experience’ is high- centuries and the passion displayed by today’s brewers in ly topical, with Tourism VISITFLANDERS regularly receiving their search for the perfect beer have made Belgium the questions and inquiries regarding beer and how it can be home of exceptional beers, unique in character and pro- best experienced. Not wanting to leave these unanswered, duced on the basis of an innovative knowledge of brew- we have compiled a regularly updated ‘trade’ brochure full ing. It therefore comes as no surprise that Belgian brew- of information for tour organisers. We plan to provide fur- ers regularly sweep the board at major international beer ther information in the form of more in-depth texts on competitions. certain subjects. 3 4 In this brochure you will find information on the following subjects: 6 A brief history of Belgian beer ............................. 6 Presentations of Belgian Beers............................. 8 What makes Belgian beers so unique? ................12 Beer and Flanders as a destination ....................14 List of breweries in Flanders and Brussels offering guided tours for groups .......................18 8 12 List of beer museums in Flanders and Brussels offering guided tours .......................................... 36 Pubs ..................................................................... 43 Restaurants .........................................................47 Guided tours ........................................................51 List of the main beer events in Flanders and Brussels ......................................... 58 Facts & Figures .................................................... 62 18 We hope that this brochure helps you in putting together your tours. Anything missing? Any comments? 36 43 Contact your Trade Manager, contact details on back cover.