History Walks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Isle of Arran Adventure – 3 Day Tour from Edinburgh Or Glasgow

Rabbies Solutions LLP. 6 Waterloo Place, Edinburgh, EH1 3EG Scotland. Tel: +44(0) 131 226 3133 Fax: +44(0) 131 225 7028 Email: [email protected] Web: www.rabbies.com ISLE OF ARRAN ADVENTURE – 3 DAY TOUR FROM EDINBURGH OR GLASGOW The Isle of Arran is nicknamed ‘Scotland in miniature’. This is because you find all the best bits of Scotland packed into 452 square kilometres. Dramatic peaks, lush valleys, abandoned beaches, standing stones, caves and castles: Arran can keep you entertained for weeks! So, journey the short distance through Ayrshire and Burns Country to lovely Arran and you’ll want to return again and again. Day 1: Your Rabbie’s driver-guide picks you up from your accommodation in the morning. We want to take advantage of this private tour and spend as much time on Arran as possible! So, if you’re starting your tour from Glasgow you make the short drive to Ardrossan for your ferry to Arran in the late morning. And If you’re starting from Edinburgh, you make a comfort stop en-route. You catch the ferry to the Isle of Arran at Ardrossan and disembark in Brodick. South from here in Lamlash, your guide can reveal to you The Holy Isle across the water, owned by the Samye Ling Buddhist Community. VAT Registration No. 634 8216 38 Registered in Scotland No. SC164516 6 Waterloo Place, Edinburgh EH1 3EG Rabbies Solutions LLP. 6 Waterloo Place, Edinburgh, EH1 3EG Scotland. Tel: +44(0) 131 226 3133 Fax: +44(0) 131 225 7028 Email: [email protected] Web: www.rabbies.com You head to the stunning beach at Whiting Bay and have a stroll along the white, sandy beach and enjoy the view of the lighthouse. -

A BRIEF HISTORY of ST MOLIOS CHURCH SHISKINE This Booklet Is a Brief History of Church Life in and Round Shiskine, and in Particular of St Molios Church

A BRIEF HISTORY OF ST MOLIOS CHURCH SHISKINE This booklet is a brief history of church life in and round Shiskine, and in particular of St Molios Church. The Red Church was opened for worship on 21st July 1889. This event testified to the faith and commitment of generations of Christian people. The expansion has continued. In 1962 a Guild Room and kitchen were added to the church. In 1964 the kitchen and Vestry were let out to the Board of health twice a week for physiotherapy. Thereafter the toilets were altered to ensure access, for disabled people and improvements to the kitchen and hall were carried out. The profits generated by this booklet will benefit the fund set up to enable improvements to the Church & Hall. The new manse was built in 1978. Services on Sunday are well attended both by our members and visitors who flock to the island every year. The church of Scotland has adjusted ministry on the island so that since 2005 our parish has been linked not only to Lochranza and Pirnmill, but also to Brodick & Corrie. The arrangement is made possible by the appointment of a minister and a part-time Parish Assistant resident in Shiskine manse. The Minister and Reader conduct three services each on a Sunday, ensuring the tradition of morning worship can continue. Worship is always at 12:00 noon at St. Molios. Visitors to other churche in the linkage need to consult "The Arran Banner" or the church notice board for times of services which vary. The Sunday Club meets at the time of morning worship weekly during term-time and is open to children from four to eleven. -

Ayrshire & the Isles of Arran & Cumbrae

2017-18 EXPLORE ayrshire & the isles of arran & cumbrae visitscotland.com WELCOME TO ayrshire & the isles of arran and cumbrae 1 Welcome to… Contents 2 Ayrshire and ayrshire island treasures & the isles of 4 Rich history 6 Outdoor wonders arran & 8 Cultural hotspots 10 Great days out cumbrae 12 Local flavours 14 Year of History, Heritage and Archaeology 2017 16 What’s on 18 Travel tips 20 VisitScotland iCentres 21 Quality assurance 22 Practical information 24 Places to visit listings 48 Display adverts 32 Leisure activities listings 36 Shopping listings Lochranza Castle, Isle of Arran 55 Display adverts 37 Food & drink listings Step into Ayrshire & the Isles of Arran and Cumbrae and you will take a 56 Display adverts magical ride into a region with all things that make Scotland so special. 40 Tours listings History springs to life round every corner, ancient castles cling to spectacular cliffs, and the rugged islands of Arran and Cumbrae 41 Transport listings promise unforgettable adventure. Tee off 57 Display adverts on some of the most renowned courses 41 Family fun listings in the world, sample delicious local food 42 Accommodation listings and drink, and don’t miss out on throwing 59 Display adverts yourself into our many exciting festivals. Events & festivals This is the birthplace of one of the world’s 58 Display adverts most beloved poets, Robert Burns. Come and breathe the same air, and walk over 64 Regional map the same glorious landscapes that inspired his beautiful poetry. What’s more, in 2017 we are celebrating our Year of History, Heritage and Archaeology, making this the perfect time to come and get a real feel for the characters, events, and traditions that Cover: Culzean Castle & Country Park, made this land so remarkable. -

Itinerary Sample

VisitArran, Brodick Pier, Isle of Arran KA27 8AU www.visitarran.com Sample Itinerary - North Arran 2021 1000 Depart Brodick 1015 Arrive Brodick Castle – Brodick Castle is the former ancestral home of the Dukes of Hamilton. Now run by the National Trust for Scotland, the Castle displays an unrivalled collection of antiquities, including the Beckford Collection. The gardens are also superb, with a children’s adventure playground, walled garden, Fairy Trail and other walks. 1200 Depart Brodick Castle for Lochranza Distillery 1230 Lunch at Distillery, followed by a Copper Tour. Lochranza Distillery is independently owned by Isle of Arran Distillers. It was voted the #1 Visitor Experience in Scotland by the Association of Scottish Visitor Attractions in 2019! 1400 Visit to Arran Geopark hub at Lochranza Centre. The Arran Geopark aims to promote and conserve Arran’s spectacular and globally important geology. Find out more about Arran’s formation, which has some of the key geological discovery sites in the UK. 1430 Leave Geopark and head to Lochranza Castle. This 16thC tower house was built by the McSweens on a peninsula extending into the beautiful loch. In summer you can wander around the building. 1445 Head south to to Blackwaterfoot, on the C147. Pass Machrie Standing Stones, and Kings Caves. If you choose to walk, each route is approximately 90mins return from/to the respective car park. Sturdy footwear is essential. 1515 Continue on the the C147 to Blackwaterfoot and the B880 back to Brodick. 1545 Home Farm Visitor Centre with: Arran Aromatics – factory shop with beautiful toiletries and candles made on Arran Arran Cheese Shop - lovely flavoured cheddars and an award winning Arran Blue cheese. -

Clyde River Steamer Club Founded 1932

Clyde River Steamer Club Founded 1932 Nominated Excursion aboard MV Hebrides to Arran th Saturday 12 January 2013 For the New Year excursion in 2013, the Clyde River Steamer Club has again decided to organise a trip to the Isle of Arran. Caledonian MacBrayne have confirmed that during the annual overhaul period of MV CALEDONIAN ISLES , it is the intention that MV HEBRIDES will be deployed on the Ardrossan-Brodick service. This will be the first time MV HEBRIDES has served on the Arran run and her first spell of service on the Clyde. The attractive price of £25.00 per adult (£10.00 per child – under 18) includes: - Return ferry travel to and from Brodick on MV HEBRIDES. - A photographic opportunity in Brodick on the outward journey. - A private coach tour round the north of Arran passing through the villages of Corrie, Sannox, Lochranza, Catacol and Pirnmill to Blackwaterfoot. - A two course meal (menu below) with tea or coffee at the Kinloch Hotel, Blackwaterfoot. - Free time in Brodick prior to catching the return sailing to Ardrossan at 1640. Advance tickets are available at the above reduced rate by post from the Cruising Coordinator at the address below. As places are limited book early to avoid disappointment. Bookings received after Friday 4 January will be subject to a higher rate. Please note that lunch options must be selected from the options below at the time of booking. ********** Alternatively book ONLINE at www.crsc.org.uk ********** Itinerary: Ardrossan dep 0945 Brodick arrive 1040 Brodick dep (coach) 1115 via North Arran to Blackwaterfoot ******** Lunch at Kinloch Hotel between 1230 and 1430 ******** Blackwaterfoot dep (coach) 1430 via ‘The String’ road to Brodick Brodick dep 1640 Ardrossan arrive 1735 The final itinerary of the day may be subject to alteration, dependant on weather and other circumstances. -

5 Gazetteer of Pitchstone Outcrops on the Isle of Arran

5 GAZETTEER OF PITCHSTONE OUTCROPS ON THE ISLE OF ARRAN North Arran (the ‘Granite’) disintegration, depressed below the level of the granite. [. .] The pitchstone is decomposed into a thin 1. Beinn a’ Chliabhain white film in many places along the outer edge of the NGR: NR 970 407 dyke, next to the granite, in consequence, probably, of A composite dyke with basic sides and a pitchstone the oxidation and removal of the iron which enters centre occurs 50m north of the highest point (675m), into its composition. The dyke is in some parts of its and again 300m to the east. course obscured by debris, but upon the whole is, Porphyritic, colour unknown. perhaps, the best defined dyke of this rock occurring Gunn et al 1903, 94; Tyrrell 1928, 207. anywhere in the granite of Arran.’ (Bryce 1859, 100). 2. Beinn Nuis Porphyritic, grey-green to dark green. NGR: NR 958 394 Gunn et al 1903, 94; Tyrrell 1928, 208. A pitchstone dyke, 2m wide, is found approximately 4. Beinn Tarsuinn II 500m south-east of the summit. NGR: NR 961 415 Porphyritic, grey-green to dark green. No information available. Gunn et al 1903, 94; Tyrrell 1928, 208. Porphyritic, grey-green to dark green. 3. Beinn Tarsuinn I BGS, Arran, 1:50,000, Solid edition, 1987; Ballin NGR: NR 958 411 (2006 survey). A pitchstone outcrop is visible 150m south-west of 5. Caisteal Abhail I the summit. There are probably other small outcrops NGR: NR 966 437 on this hill. ‘One [dyke] is of green pitchstone, and On the ridge between Cir Mhor and Caisteal Abhail, cuts the granite sheer through in a north and south a pitchstone dyke occurs in the cliff a little south-east direction from bottom to top of the cliff. -

Two Story Cottage Offers IRO £320,000

Offers IRO £320,000 IRO Offers Room Room, Bedroom 2 with washbasin, Bedroom 3 with En-suite Shower En-suite with 3 Bedroom washbasin, with 2 Bedroom Room, Croftbank, Lochranza, Isle of Arran, KA27 8HL 8HL KA27 Arran, of Isle Lochranza, Croftbank, Lounge, Family Bathroom, Top Landing, Bedroom 1, En-suite Shower En-suite 1, Bedroom Landing, Top Bathroom, Family Lounge, Entrance Vestibule, Dining Room, Fitted Dining Kitchen, Utility Room, Utility Kitchen, Dining Fitted Room, Dining Vestibule, Entrance Two Story Cottage Cottage Story Two ACCOMMODATION www.jascampbell.co.uk 01294 602000 01294 Travelling Directions: Home Report Available to download on the GSPC website From Brodick ferry terminal turn right and follow the signs to quoting the properties individual reference Lochranza. The property sits slightly back from the road on the number which can be found at the bottom of the left hand side, opposite a phone box. schedule. viewing By arrangement with Messrs Jas Campbell & Co, WS on 01294 60 2000, Evenings 5 - 9pm, Sat/Sun 10.30am - 4pm on 0141 572 4374. Once you have viewed the property should you wish to arrange a survey, please contact our Property Manager. offers All further negotiations and all offers to be lodged with Messrs Jas Campbell & Co, WS. Bank of Scotland buildings, Saltcoats. mortgages We are pleased to offer intending purchasers any financial guidance which they may require and comprehensive advice from fully qualified Solicitors. We are able to offer a full and comprehensive mortgage service in conjunction with all leading banks and building societies. Up to 100% mortgages may be arranged according to status. -

Arran Field Trip 2014

SOEE3291/SOEE5690 Atmospheric Science Field Skills Arran field trip 2014 This document provides you with information on: Fieldtrip dates Departure times from Leeds and Lochranza Accommodation Course payment information for those who are taking the module as an option List of equipment Please find enclosed fieldtrip information and if you require any further details, please do not hesitate to contact the module leader Jim McQuaid ([email protected]) Accommodation We will be staying at the Lochranza Field Centre, Lochranza, Isle of Arran, KA27 8HL Telephone: 01770 830 637, Fax: 01770 830 205, http://www.pgl.co.uk/lochranza/ The telephone number above is for emergency use only. A payphone is available at the centre. The field centre has a no alcohol policy so please do not bring any with you, you will have the opportunity to spend evenings in the local pub for such refreshments! There is no local cash machine so bring sufficient cash for the week. Departure time from Leeds on Friday 6th September. We will leave by coach promptly at 8.00 am from outside the Parkinson Building (the white clock tower building at the front entrance of the University. Please congregate on the steps outside this building, beneath the clock tower). The early start is because we are catching the 3.15 pm ferry from Ardrossan to Brodick and need to check-in for the ferry at Ardrossan harbour, North Ayrshire, Scotland by 2.30 pm. Because of the traveltime and ferry sailing time, we can NOT wait past 8.00 am for anyone. -

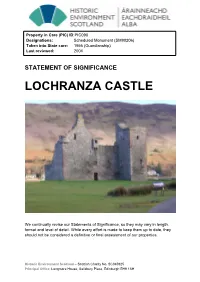

Lochranza Castle Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC090 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90206) Taken into State care: 1956 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2004 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE LOCHRANZA CASTLE We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH LOCHRANZA CASTLE BRIEF DESCRIPTION Lochranza Castle occupies a low, gravelly peninsula projecting into Loch Ranza on the north coast of Arran and was constructed during the late 13th or early 14th centuries as a two-storey hall house. -

Macdonald Bards from Mediaeval Times

O^ ^^l /^^ : MACDONALD BARDS MEDIEVAL TIMES. KEITH NORMAN MACDONALD, M.D. {REPRINTED FROM THE "OBAN TIMES."] EDINBURGH NORMAN MACLEOD, 25 GEORGE IV. BRIDGE. 1900. PRBPACB. \y^HILE my Papers on the " MacDonald Bards" were appearing in the "Oban Times," numerous correspondents expressed a wish to the author that they would be some day presented to the pubUc in book form. Feeling certain that many outside the great Clan Donald may take an interest in these biographical sketches, they are now collected and placed in a permanent form, suitable for reference ; and, brief as they are, they may be found of some service, containing as they do information not easily procurable elsewhere, especially to those who take a warm interest in the language and literature of the Highlands of Scotland. K. N. MACDONALD. 21 Clarendon Crescknt, EDINBURGH, October 2Uh, 1900. INDEX. Page. Alexander MacDonald, Bohuntin, ^ ... .. ... 13 Alexander MacAonghuis (son of Angus), ... ... ... 17 Alexander MacMhaighstir Alasdair, ... ... ... ... 25 Alexander MacDonald, Nova Scotia, ... .. .. ... 69 Alexander MacDonald, Ridge, Nova Scotia, ... ... .. 99 Alasdair Buidhe MacDonald, ... .. ... ... ... 102 Alice MacDonald (MacDonell), ... ... .. ... ... 82 Alister MacDonald, Inverness, ... ... .. ... ... 73 Alexander MacDonald, An Dall Mòr, ... ... ... .. 43 Allan MacDonald, Lochaber, ... ... ... ... .. 55 Allan MacDonald, Ridge, Nova Scotia, ... .... ... ... 101 Am Bard Mucanach (Tlie Muck Bard), ... ... .. ... 20 Am Bard CONANACH (The Strathconan Bard), .. ... ... 48 An Aigeannach, -

324 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

324 bus time schedule & line map 324 Brodick Ferry Terminal - Blackwaterfoot View In Website Mode The 324 bus line (Brodick Ferry Terminal - Blackwaterfoot) has 4 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Blackwaterfoot: 8:00 AM - 7:05 PM (2) Brodick: 6:38 AM - 5:35 PM (3) Lamlash: 7:38 AM (4) Shiskine: 8:41 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 324 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 324 bus arriving. Direction: Blackwaterfoot 324 bus Time Schedule 35 stops Blackwaterfoot Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 10:55 AM - 7:05 PM Monday 8:00 AM - 7:05 PM Ferry Terminal, Brodick Tuesday 8:00 AM - 7:05 PM Douglas Hotel, Brodick A841, Scotland Wednesday 8:00 AM - 7:05 PM Royal Bank, Brodick Thursday 8:00 AM - 7:05 PM Friday 8:00 AM - 9:35 PM Manse Road, Brodick Saturday 8:00 AM - 7:05 PM Auchrannie Road, Brodick Shore Road, Scotland Brodick Golf Course, Brodick 324 bus Info Douglas Place, Brodick Direction: Blackwaterfoot Stops: 35 Heritage Museum, Brodick Trip Duration: 82 min Line Summary: Ferry Terminal, Brodick, Douglas Home Farm, Brodick Hotel, Brodick, Royal Bank, Brodick, Manse Road, Brodick, Auchrannie Road, Brodick, Brodick Golf Course, Brodick, Douglas Place, Brodick, Heritage Gardeners Cottage, Brodick Museum, Brodick, Home Farm, Brodick, Gardeners Cottage, Brodick, Brodick Castle Entrance, Brodick, Brodick Castle Entrance, Brodick Buccanneers Cottage, High Corrie, Corrie Terrace, High Corrie, Corrie Craft And Antiques, Corrie, Buccanneers Cottage, High Corrie Sannox Quay, Sannox, Sannox -

Forestry Shelves Link-Road Plans Conkers! U-Turn on Road Will Force Rethink for Arran's Harvest Strategy

30th October 2008 / The Arran Voice Ltd Tel: 01770 303 636 E-mail: [email protected] 30th October 2008 — 082 65p Forestry shelves link-road plans CONKERS! U-turn on road will force rethink for Arran's harvest strategy After harvesting of forests like those around Meall Buidhe, the Forestry will have to deal with Arran's more remote western plantations DUE TO HIGH costs and environmental timber haulage route which would link concerns, the Forestry Commission the String Road and the Ross Road has opted to postpone plans to but we've decided to shelve it for the develop a road connecting Shedog and moment,' a forestry spokesman told The Glenscorrodale forests. The route was Arran Voice earlier this week. 'A thorough suggested as part of major strategy to assessment of the route showed it would harvest the large stock of mature timber be prohibitively expensive,' he added. now mounting on the island. Designed The proposed link between Shedog as a way of relieving some of the and Kilpatrick via Beinn Tarsuinn — pressure on both the Ross and the String planned to avert the need to shuttle roads, it would have diverted harvested timber lorries on the Ross Road — has timber from forest areas in the west also been shelved. It was estimated (Shedog and Kilpatrick) directly down that the construction of the forestry the Monamore Glen into Lamlash and roads would cost in excess of £700,000 then north to the Brodick loading slip and the Forestry was keen to benefit on Market Road. from £317,000 from the government’s Strategic Timber Transport Fund.