Bees at War: Interspecific Battles and Nest Usurpation in Stingless Bees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Classification of the Apidae (Hymenoptera)

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Mi Bee Lab 9-21-1990 Classification of the Apidae (Hymenoptera) Charles D. Michener University of Kansas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/bee_lab_mi Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Michener, Charles D., "Classification of the Apidae (Hymenoptera)" (1990). Mi. Paper 153. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/bee_lab_mi/153 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Bee Lab at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mi by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 4 WWvyvlrWryrXvW-WvWrW^^ I • • •_ ••^«_«).•>.• •.*.« THE UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS SCIENC5;^ULLETIN LIBRARY Vol. 54, No. 4, pp. 75-164 Sept. 21,1990 OCT 23 1990 HARVARD Classification of the Apidae^ (Hymenoptera) BY Charles D. Michener'^ Appendix: Trigona genalis Friese, a Hitherto Unplaced New Guinea Species BY Charles D. Michener and Shoichi F. Sakagami'^ CONTENTS Abstract 76 Introduction 76 Terminology and Materials 77 Analysis of Relationships among Apid Subfamilies 79 Key to the Subfamilies of Apidae 84 Subfamily Meliponinae 84 Description, 84; Larva, 85; Nest, 85; Social Behavior, 85; Distribution, 85 Relationships among Meliponine Genera 85 History, 85; Analysis, 86; Biogeography, 96; Behavior, 97; Labial palpi, 99; Wing venation, 99; Male genitalia, 102; Poison glands, 103; Chromosome numbers, 103; Convergence, 104; Classificatory questions, 104 Fossil Meliponinae 105 Meliponorytes, -

Tetragonula Carbonaria and Disease: Behavioural and Antimicrobial Defences Used by Colonies to Limit Brood Pathogens

Tetragonula carbonaria and disease: Behavioural and antimicrobial defences used by colonies to limit brood pathogens Jenny Lee Shanks BHort, BSc (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Submitted to the School of Science and Health University of Western Sydney, Hawkesbury Campus July, 2015 Our treasure lies in the beehive of our knowledge. We are perpetually on the way thither, being by nature winged insects and honey gatherers of the mind. Friedrich Nietzsche (1844 – 1900) i Statement of Authentication The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original except as acknowledged in the text. I hereby declare that I have not submitted this material, whether in full or in part, for a degree at this or any other institution ……………………………………………………………………. Jenny Shanks July 2015 ii Acknowledgements First and foremost, I am extremely indebted to my supervisors, Associate Professor Robert Spooner-Hart, Dr Tony Haigh and Associate Professor Markus Riegler. Their guidance, support and encouragement throughout this entire journey, has provided me with many wonderful and unique opportunities to learn and develop as a person and a researcher. I thank you all for having an open door, lending an ear, and having a stack of tissues handy. I am truly grateful and appreciate Roberts’s time and commitment into my thesis and me. I am privileged I had the opportunity to work alongside someone with a wealth of knowledge and experience. Robert’s passion and enthusiasm has created some lasting memories, and certainly has encouraged me to continue pursuing my own desires. -

Revista Biologia Tropical

VOLUMEN 21 1973 SUPLEMENTO 1 UNIVERSIDAD DE COSTA RICA REVISTA BIOLOGIA TROPICAL THE NEST ARCHITECTURE OF STINGlESS BEES WITH SPECIAl REFERENCE TO THOSE OF COSTA RICA (Hymenoptera, Apidae) A. WILLE and c. D. MICHENER THE NEST ARCHITECTURE OF STINGLESS BEES WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THOSE OF COSTA RICA (Hymenoptera, Apidae) 2 by Alvaro Wille 1 and Charles D. Michener CONTENTS Introduetion ...................................................................... .................................. 9 Classifieation and Nomenclature .......................................................................... 17 Nest Loeations ........................................ ...... ............ ............ ...................... ......... 17 A. General Aecount ..... .............. ............ ................ .................. .......... .... 17 B. Sites of Costa Riean Nests Studied ..................................... ............... 38 Nest Struetures ... ................. ........................ ....... ........... ..................................... 38 A. Terminology and Nest Organization .................................................. 38 l. Materials ... ......................................... ...................................... 38 2. Organization and terminology...... ............................................ 38 B. Tabular Summary of Meliponine Nest Strueture ............................... 41 1. Content and methods ............................................................... 41 2. Symbols used in the tables .... ...... ............................................ -

Warfare in Stingless Bees

Insect. Soc. (2016) 63:223–236 DOI 10.1007/s00040-016-0468-0 Insectes Sociaux REVIEW ARTICLE Warfare in stingless bees 1,2 1,3 4 5 C. Gru¨ter • L. G. von Zuben • F. H. I. D. Segers • J. P. Cunningham Received: 24 August 2015 / Revised: 28 January 2016 / Accepted: 6 February 2016 / Published online: 29 February 2016 Ó International Union for the Study of Social Insects (IUSSI) 2016 Abstract Bees are well known for being industrious pol- how victim colonies are selected, but a phylogenetically linators. Some species, however, have taken to invading the controlled analysis suggests that the notorious robber bee nests of other colonies to steal food, nest material or the nest Lestrimelitta preferentially attacks colonies of species with site itself. Despite the potential mortality costs due to more concentrated honey. Warfare among bees poses many fighting with an aggressive opponent, the prospects of a interesting questions, including why species differ so large bounty can be worth the risk. In this review, we aim to greatly in their response to attacks and how these alternative bring together current knowledge on intercolony fighting strategies of obtaining food or new nest sites have evolved. with a view to better understand the evolution of warfare in bees and identify avenues for future research. A review of Keywords Stingless bees Á Warfare Á literature reveals that at least 60 species of stingless bees are Alternative foraging strategies Á Cleptoparasitism Á involved in heterospecific conflicts, either as attacking or Lestrimelitta Á Meliponini victim colonies. The threat of invasion has led to the evo- lution of architectural, behavioural and morphological adaptations, such as narrow entrance tunnels, mud balls to Introduction block the entrance, decoy nests that direct invaders away from the brood chamber, fighting swarms, and soldiers that The nest is the all-important centre of the bee’s universe, are skilled at immobilising attackers. -

Stingless Bee Propagation

23/08/2018 Stingless Bee Propagation NATURAL PROPAGATION Stingless bees do not swarm the same as honey bees. Instead they set up a new nest site, stock it with food and then move in. Can take weeks, months, or years! So we need artificial propagation techniques Australian Native Bee Book, pg110 Tetragonula carbonaria Austroplebeia australis Tetragonula hockingsi Austroplebeia cassiae Tetragonula davenporti Austroplebeia essingtoni Tetragonula mellipies Austroplebeia magna Tetragonula sapiens Tetragonula clypearis Austroplebeia cincta 2 years and waiting for a queen (Green species also found in PNG or S.E. Asia) A.australis Bees in S.E. QLD My mentors T.hockingsi Robert Luttrell > 10,000 workers More than 300 hives Coastal QLD Commercial sales Brisbane to Cape York Educator Vigorous Inventor Trouble makers A.australis Allan Beil Small or large colonies (talking to Nick Powell) Drier Inland areas More than 300 hives Found in most states A.australis Can handle droughts Shy Naturalist Very gentle Dr Tim Heard T.carbonaria More than 300 hives 10,000 workers Author / Educator Coastal Bundaberg to Bega Commercial sales Vigorous Researcher Less troublesome than hockingsi 1 23/08/2018 Boxes / Pests / Heat / Cold > Need a better box than Apis. Sealed against pests and thick enough to insulate from heat and cold > Hard to transfer. Want a box to resist weather, to last 20 years plus • Syrphid fly (left) • Phorid fly (below) 1. Splitting or Division • Divides a colony into 2 equal parts every 12 to 18 months • Each box gets half the provisions and half the brood • There are always queen cells and virgin queens • Split when the hive contents are > 3kg (net) and the weather is kind • Tim Heard is an early user of this technique. -

Bees at War: Interspecific Battles and Nest Usurpation in Stingless Bees

The University of Chicago Bees at War: Interspecific Battles and Nest Usurpation in Stingless Bees. Author(s): John Paul Cunningham, James P. Hereward, Tim A. Heard, Paul J. De Barro, and Stuart A. West Source: The American Naturalist, Vol. 184, No. 6 (December 2014), pp. 777-786 Published by: The University of Chicago Press for The American Society of Naturalists Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/678399 . Accessed: 07/10/2015 00:46 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press, The American Society of Naturalists, The University of Chicago are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The American Naturalist. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 23.235.32.0 on Wed, 7 Oct 2015 00:46:53 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions vol. 184, no. 6 the american naturalist december 2014 Natural History Note Bees at War: Interspecific Battles and Nest Usurpation in Stingless Bees John Paul Cunningham,1,* James P. Hereward,2 Tim A. Heard,3 Paul J. De Barro,3 and Stuart A. West4 1. Queensland University of Technology, Gardens Point, Brisbane, Queensland 4001, Australia; 2. -

CROSS-POLLINATOR Issue 19, March 2021 Inside This Issue Newsletter of the Message from Committee

The CROSS-POLLINATOR Issue 19, March 2021 Inside this issue Newsletter of the Message from committee ............ 2 Australian Native Bee Association Feature article - Bee hotels .......... 3 Stingless Bee Survey results ......... 6 Research highlights ...................... 7 https://australiannativebee.org.au/ https://www.facebook.com/Australian.Native.Bee.Association/ Book Review ................................ 8 https://www.instagram.com/australiannativebeeassociation/ Native Bee events ..................... 10 New book ................................. 11 Original articles, new information and news Branch News.............................. 12 from the world of native bees Branch Contacts ........................ 14 Dr Laura Brettell is inspecting some of the occupants of a hard- wood block in an apple orchard in Orange, NSW. Read this issue’s feature article to learn more. The Cross-Pollinator, March 2021 Page 1 The ISSN 2652-8010 The Australian Native Bee Associa- CROSS- tion Inc promotes the conservation Circulation: ANBA Members (currently 575) POLLINATOR and sustainable use of all Australi- MARCH 2021 Contributions: Please send to an native bees. ANBA achieves that [email protected] by providing resources, dissemi- Disclaimer The Cross-Pollinator is a forum to people to express their views nating information, supporting and observations. The author of each article is responsible for the statements members and communicating with expressed within; their opinions are not necessarily those of the ANBA. stakeholders. Message from the Management Committee the results of our tests of four species of stingless bee honey: hockingsi, carbonaria, australis and cassiae. This Dear members, testing for common food microbiology and honey chem- Welcome to another issue of our Newsletter. Inside find a istry tests will help support our application for native feature articles on bee hotels; a sneak peak of the early stingless bee honey to be a standardised food. -

How Stingless Bees Are Able to Make Tall Spiral Nests 29 July 2020, by Bob Yirka

How stingless bees are able to make tall spiral nests 29 July 2020, by Bob Yirka not just architecturally impressive, but were mesmerizing in their beauty. At the time, scientists had no explanation for how such a simple creature could create such magnificent structures out of nothing but wax. A closer look showed that the bees created their cells in hexagonal shapes then added regurgitated food, and then the queen deposited a single egg in the cell. The researchers with this new effort were at the time studying similar patterns in crystals and in mother-of-pearl created by mollusks. After finding that such patterns could be created by applying a very simple algorithm, the researchers turned their attention to the bees in Australia. To find out if the bees were using a similar algorithm, the researchers modeled their attributes and behaviors on a computer to create a simulation of their nest-building behavior. In so doing, they Combs of two species of the stingless bee Tetragonula discovered that the bees could very easily create showing structures of (a) target patterns (Tetragonula spiral structures by following two very simple rules. carbonaria), (b) spirals (Tetragonula carbonaria), (c) When it was time to build a new cell, they could add double spirals (Tetragonula carbonaria) and (d) more disordered terraces (Tetragonula hockingsi). Images a cell to the growth front, which was the edge of the courtesy of (a) Elke Haege; (b–d) Tim Heard. Credit: comb under construction—but it had to be placed Journal of The Royal Society Interface (2020). DOI: slightly higher than its neighbors—or they could build 10.1098/rsif.2020.0187 a new cell on top of another cell, provided it was level in comparison with the other cells in the nest. -

Bee Behavioural Plasticity in a Global Change Context Miguel Ángel Collado Aliaño

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi queda condicionat a lʼacceptació de les condicions dʼús establertes per la següent llicència Creative Commons: http://cat.creativecommons.org/?page_id=184 ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis queda condicionado a la aceptación de las condiciones de uso establecidas por la siguiente licencia Creative Commons: http://es.creativecommons.org/blog/licencias/ WARNING. The access to the contents of this doctoral thesis it is limited to the acceptance of the use conditions set by the following Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/?lang=en Estación Biológica de Doñana & Centre de Recerca Ecològica i Aplicacions Forestals Bee behavioural plasticity in a global change context | Miguel Ángel Collado Aliaño Ignasi Bartomeus Roig Daniel Sol Rueda 4 Bee behavioural plasticity in a global change context | Page Prólogo ............................................................................................................................................................... 7 General abstract ........................................................................................................................................... 9 General introduction: ...................................................................................................................................... 11 The status of global change in pollinators .................................................................................. 11 Animals facing new challenges ........................................................................................................ -

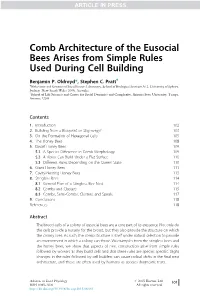

Comb Architecture of the Eusocial Bees Arises from Simple Rules Used During Cell Building

ARTICLE IN PRESS Comb Architecture of the Eusocial Bees Arises from Simple Rules Used During Cell Building Benjamin P. Oldroyd*, Stephen C. Pratt† *Behaviour and Genetics of Social Insects Laboratory, School of Biological Sciences A12, University of Sydney, Sydney, New South Wales 2006, Australia †School of Life Sciences and Centre for Social Dynamics and Complexity, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona, USA Contents 1. Introduction 102 2. Building from a Blueprint or Stigmergy? 103 3. On the Formation of Hexagonal Cells 105 4. The Honey Bees 108 5. Dwarf Honey Bees 109 5.1 A Species Difference in Comb Morphology 109 5.2 A. florea Can Build Under a Flat Surface 110 5.3 Different Rules Depending on the Queen State 110 6. Giant Honey Bees 111 7. Cavity-Nesting Honey Bees 113 8. Stingless Bees 114 8.1 General Plan of a Stingless Bee Nest 114 8.2 Combs and Clusters 115 8.3 Combs, Semi-Combs, Clusters, and Spirals 117 9. Conclusions 118 References 118 Abstract The brood cells of a colony of eusocial bees are a core part of its existence. Not only do the cells provide a nursery for the brood, but they also provide the structure on which the colony lives. As such, the comb structure is itself under natural selection to provide an environment in which a colony can thrive. Via examples from the stingless bees and the honey bees, we show that aspects of nest construction arise from simple rules followed by workers as they build cells and that these rules are species specific. -

Mandurama Public School Term 2

Mandurama Public School Term 2 Aim High Grow Strong! Week 4 What’s inside: Student of the Week is • Student of the Week Carly Alloway • Summer & Winter uniform • Principal’s message • Student Work • Local Advertisements • What’s been happening What’s on: Thursday 13th May—Book club orders due. Mon 17th May - Year 6 orientation day at Blayney High Carly is one of our Year 6 students and a Wed 19th to Fri 21st May— school leader. She always does her best Wambangalang excursion for Stg 2. in all endeavours and is achieving high Thurs 27th May—Musica Viva perfor- results in Mathematics and applies her- mance in Canowindra. self to all areas of her work. Carly did an exceptional job when painting her stones for Mothers’ Day but also willingly assist- ed her peers with theirs and provided great suggestions for colour mixing. Principal’s Message Mrs Brill is enjoying a short holiday in South Australia but will return next week. In her ab- sence students have maintained normal class- room routines and continued to improve their skills in Mathematics and English. They have been familiarising themselves with the new Lit- eracy boxes and are developing their compre- hension skills. We are studying immigration in History and Na- tional Parks in Geography. We are hoping to be able to visit Blue Mountains National Park later this term. Year 6 students have their 2nd orientation day at Blayney High School on Monday 17th May and we wish them well on the day. Stage 2 students are organised and excited in anticipation of their overnight excur- sion to Wambangalang next week. -

April 2021 CANCELLED ROGI News ROGI Meetings Are Held on the 2Nd Inside This Edition Page Thursday Night of the Month, with Doors Opening at 6.15Pm

Next meeting: Thursday 8 April 2021 CANCELLED ROGI News ROGI meetings are held on the 2nd Inside this edition Page Thursday night of the month, with doors opening at 6.15pm. Members President’s Message 2 can visit the plant table, seed bank, library and stalls or just have a chat Coming Events. Membership 3 before the meeting. Please be seated April Meeting CANCELLED 3 by 7pm ready for the proceedings. March Meeting—Russell Zabel 4-6 Plant Clinic 7 Bayside Community Church Banana Weevil. Fruit Piercing Moth 8,9 Cnr McDonald Rd & Macarthur St Plant of the Month—Dragon Fruit 10-12 ALEXANDRA HILLS Recipes. Plant Identification 12 Don’t forget: Seed Savers News. Biodynamics SG 13 • Pay your membership dues (only ROGI Garden Visits & Field Trips 14 fully paid members may attend) Upcoming Garden Events 14 • Observe social distancing Oaklands St Bed Prep Workshop 15 • BYO mug if you want tea/coffee How I Make Compost 16,17 • There will be no supper Leafcutter Bee. Used Pots Needed 17 • Swap and share has resumed Seed Sowing Guide 18 • ROGI Rewards has resumed • Bring a basket/box/bag for your ROGI Committee and Office Bearers 19 purchases Punnets Needed. Deadline 19 Native bees (Tetragonula carbonaria species) were • Return washed seedling pots enjoying nectar from this nasturtium. To learn more • Any questions for Plant Clinic about these amazing creatures, read the report on our March speaker Russell Zabel on p. 4-6. leftovers instead of throwing them away. At the very least give the spoiled leftovers to the compost bin, worm farm, Bokashi or Jill’s Jottings chooks.