Sponsors of the Oil Sands Oral History Project Include the Alberta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MINES and MINERALS Exploration and Development Continued Not

538 MINES AND MINERALS Exploration and development continued not only unabated but accelerated. During 1948 rotary bits drilled 1,663,687 ft. into the earth compared with 882,358 ft. in 1947 and 401,920 ft. in 1946. At the end of the year, 65 exploration parties were carrying out operations, most of them north of the North Saskatchewan River. The 1948 revenue to Alberta crude oil producers amounted to $35,127,751 as compared with $18,078,907 in 1947. Early in 1949, the capacity of the Alberta refinery, estimated at 35,250 bbl. daily, was found to be insufficient to handle the average daily production of crude oil, not including natural gasoline, which was 50,673 bbl. at May 1, 1949. To remedy the situation a pipeline with a capacity of 40,000 bbl. daily is being constructed from Edmonton to the Head of the Lakes. The following table gives production by fields in 1948. 24.—Production of Alberta Oil Fields, 1948 NOTE.—Figures for total production of petroleum for 1922-46 are given at p. 473 of the 1947 Year Book' and production in the different fields for 1947 at p. 477 of the 1948-49 edition. Field Quantity Field Quantity bbl. bbl. 4,900,739 112,331 4,657,371 36,8751 648,055 17,131 Taber 201,527 30,215 189,712 179,627 Totals 10,973,583 1 Three months. The Tar Sands and Bituminous Developments*—Alberta, in its bituminous sands deposit at McMurray, has the greatest known oil reserve on the face of the earth. -

A Selected Western Canada Historical Resources Bibliography to 1985 •• Pannekoek

A Selected Western Canada Historical Resources Bibliography to 1985 •• Pannekoek Introduction The bibliography was compiled from careful library and institutional searches. Accumulated titles were sent to various federal, provincial and municipal jurisdictions, academic institutions and foundations with a request for correction and additions. These included: Parks Canada in Ottawa, Winnipeg (Prairie Region) and Calgary (Western Region); Manitoba (Depart- ment of Culture, Heritage and Recreation); Saskatchewan (Department of Culture and Recreation); Alberta (Historic Sites Service); and British Columbia (Ministry of Provincial Secretary and Government Services . The municipalities approached were those known to have an interest in heritage: Winnipeg, Brandon, Saskatoon, Regina, Moose Jaw, Edmonton, Calgary, Medicine Hat, Red Deer, Victoria, Vancouver and Nelson. Agencies contacted were Heritage Canada Foundation in Ottawa, Heritage Mainstreet Projects in Nelson and Moose Jaw, and the Old Strathcona Foundation in Edmonton. Various academics at the universities of Calgary and Alberta were also contacted. Historical Report Assessment Research Reports make up the bulk of both published and unpublished materials. Parks Canada has produced the greatest quantity although not always the best quality reports. Most are readily available at libraries and some are available for purchase. The Manuscript Report Series, "a reference collection of .unedited, unpublished research reports produced in printed form in limited numbers" (Parks Canada, 1983 Bibliography, A-l), are not for sale but are deposited in provincial archives. In 1982 the Manuscript Report Series was discontinued and since then unedited, unpublished research reports are produced in the Microfiche Report Series/Rapports sur microfiches. This will now guarantee the unavailability of the material except to the mechanically inclined, those with excellent eyesight, and the extremely diligent. -

![Yntfletic Fne]R OIL SHALE 0 COAL 0 OIL SANDS 0 NATURAL GAS](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9387/yntfletic-fne-r-oil-shale-0-coal-0-oil-sands-0-natural-gas-599387.webp)

Yntfletic Fne]R OIL SHALE 0 COAL 0 OIL SANDS 0 NATURAL GAS

2SO yntfletic fne]R OIL SHALE 0 COAL 0 OIL SANDS 0 NATURAL GAS VOLUME 28 - NUMBER 4- DECEMBER 1991 QUARTERLY Tsit Ertl Repository Artur Lakes Library C3orzdo School of M.ss © THE PACE CONSULTANTS INC. ® Reg . U.S. P.I. OFF. Pace Synthetic Fuels Report is published by The Pace Consultants Inc., as a multi-client service and is intended for the sole use of the clients or organizations affiliated with clients by virtue of a relationship equivalent to 51 percent or greater ownership. Pace Synthetic Fuels Report Is protected by the copyright laws of the United States; reproduction of any part of the publication requires the express permission of The Pace Con- sultants Inc. The Pace Consultants Inc., has provided energy consulting and engineering services since 1955. The company experience includes resource evalua- tion, process development and design, systems planning, marketing studies, licensor comparisons, environmental planning, and economic analysis. The Synthetic Fuels Analysis group prepares a variety of periodic and other reports analyzing developments In the energy field. THE PACE CONSULTANTS INC. SYNTHETIC FUELS ANALYSIS MANAGING EDITOR Jerry E. Sinor Pt Office Box 649 Niwot, Colorado 80544 (303) 652-2632 BUSINESS MANAGER Ronald L. Gist Post Office Box 53473 Houston, Texas 77052 (713) 669-8800 Telex: 77-4350 CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS A-i I. GENERAL CORPORATIONS CSIRO Continues Strong Liquid Fuels Program 1-1 GOVERNMENT DOE Fossil Energy Budget Holds Its Ground 1-3 New SBIR Solicitation Covers Alternative Fuels 1-3 USA/USSR Workshop on Fossil Energy Held 1-8 ENERGY POLICY AND FORECASTS Politics More Important than Economics in Projecting Oil Market 1-10 Study by Environmental Groups Suggests Energy Use Could be Cut in Half 1-10 OTA Reports on U.S. -

Krisenergy Ltd

NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION, DIRECTLY OR INDIRECTLY, IN OR INTO THE UNITED STATES OR TO U.S. PERSONS CIRCULAR DATED 12 DECEMBER 2016 THIS CIRCULAR IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION. If you are in any doubt as to the action that you should take, you should consult your stockbroker, bank manager, solicitor, accountant or other professional adviser immediately. If you have sold or transferred all your shares in the capital of KrisEnergy Ltd. (the “Company”) of par value US$0.00125 each (“Shares”), please forward this Circular together with the Notice of Extraordinary General Meeting and the enclosed Depositor Proxy Form or Shareholder Proxy Form (as the case may be) immediately to the purchaser or transferee or to the agent through whom the sale or transfer was effected for onward transmission to the purchaser or transferee, subject to the distribution restrictions set out in this Circular. Approval in-principle has been obtained from the Singapore Exchange Securities Trading Limited (the “SGX-ST”) for the listing and quotation of the Notes, the Warrants and the New Shares (each as defined herein) on the Main Board of the SGX-ST, subject to certain conditions. The Notes, the Warrants and the New Shares will be admitted to the Main Board of the SGX-ST and official quotation will commence after all conditions imposed by the SGX-ST are satisfied, including (in the case of Warrants) there being a satisfactory spread of holdings of the Warrants to provide for an orderly market in the Warrants. The SGX-ST assumes no responsibility for the correctness or accuracy of any of the statements made, reports contained and opinions expressed in this Circular. -

INDO Indo-Energy.Com May 2021

NYSE American: INDO indo-energy.com May 2021 1 DISCLAIMERS AND CAUTIONARY NOTE ON FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS Readers are cautioned that the securities of Indonesia Energy Corporation Limited (“IEC”) are highly speculative. No representation or warranty, expressed or implied, is or will be made and, save in the case of intention or fraud, no responsiBility or liaBility is or will be accepted by IEC or by any of its directors, employees, agents or affiliates as to or in relation to the presentation or the information contained therein or forming the Basis of this presentation or for any reliance placed on the presentation by any person whatsoever. Save in the case of intention or fraud, no representation or warranty is given and neither IEC nor any of its directors, employees, agents or affiliates assume any liaBility as to the achievement or reasonaBleness of any future projections, targets, estimates or forecasts contained in the presentation. This presentation contains or may contain forward-looking statements about IEC’s plans and future outcomes, including, without limitation, statements containing the words “anticipates”, “projected”, “potential” “Believes”, “expects”, “plans”, ”estimates” and similar expressions. Such forward-looking statements involve significant known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors which might cause IEC’s actual results, financial condition, performance or achievements (including without limitation, the results of IEC’s oil exploration and commercialization efforts as descriBed herein), or the market for energy in Indonesia, to be materially different from any actual future results, financial conditions, performance or achievements expressed or implied by such forward-looking statements. Given these uncertainties, you advised not to place any undue reliance on such forward-looking statements. -

Facts About Alberta's Oil Sands and Its Industry

Facts about Alberta’s oil sands and its industry CONTENTS Oil Sands Discovery Centre Facts 1 Oil Sands Overview 3 Alberta’s Vast Resource The biggest known oil reserve in the world! 5 Geology Why does Alberta have oil sands? 7 Oil Sands 8 The Basics of Bitumen 10 Oil Sands Pioneers 12 Mighty Mining Machines 15 Cyrus the Bucketwheel Excavator 1303 20 Surface Mining Extraction 22 Upgrading 25 Pipelines 29 Environmental Protection 32 In situ Technology 36 Glossary 40 Oil Sands Projects in the Athabasca Oil Sands 44 Oil Sands Resources 48 OIL SANDS DISCOVERY CENTRE www.oilsandsdiscovery.com OIL SANDS DISCOVERY CENTRE FACTS Official Name Oil Sands Discovery Centre Vision Sharing the Oil Sands Experience Architects Wayne H. Wright Architects Ltd. Owner Government of Alberta Minister The Honourable Lindsay Blackett Minister of Culture and Community Spirit Location 7 hectares, at the corner of MacKenzie Boulevard and Highway 63 in Fort McMurray, Alberta Building Size Approximately 27,000 square feet, or 2,300 square metres Estimated Cost 9 million dollars Construction December 1983 – December 1984 Opening Date September 6, 1985 Updated Exhibit Gallery opened in September 2002 Facilities Dr. Karl A. Clark Exhibit Hall, administrative area, children’s activity/education centre, Robert Fitzsimmons Theatre, mini theatre, gift shop, meeting rooms, reference room, public washrooms, outdoor J. Howard Pew Industrial Equipment Garden, and Cyrus Bucketwheel Exhibit. Staffing Supervisor, Head of Marketing and Programs, Senior Interpreter, two full-time Interpreters, administrative support, receptionists/ cashiers, seasonal interpreters, and volunteers. Associated Projects Bitumount Historic Site Programs Oil Extraction demonstrations, Quest for Energy movie, Paydirt film, Historic Abasand Walking Tour (summer), special events, self-guided tours of the Exhibit Hall. -

EITI Commodity Trading in Indonesia Table of Contents

Final Report EITI Commodity Trading in Indonesia Table of Contents Executive Summary .......................................................................................................... 1 Context and Background .................................................................................................. 4 Change to Consumer, and Net Importer ................................................................................ 4 Pricing and Valuation ............................................................................................................. 5 Terms of gas sales contracts ............................................................................................... 5 Indonesian Crude Price ....................................................................................................... 6 Initial Scope Recommendation & Mainstreaming .............................................................. 9 Initial recommendations ........................................................................................................ 9 Reporting Cycle ................................................................................................................... 9 Definition of First Trade ...................................................................................................... 9 Materiality – reporting to the Cargo Level ......................................................................... 9 Mainstreaming................................................................................................................... -

Realizing the Potential of North America's Abundant Natural Gas

PRUDENT DEVELOPMENT Realizing the Potential of North America’s Abundant Natural Gas and Oil Resources National Petroleum Council • 2011 PRUDENT DEVELOPMENT Realizing the Potential of North America’s Abundant Natural Gas and Oil Resources A report of the National Petroleum Council September 2011 Committee on Resource Development James T. Hackett, Chair NATIONAL PETROLEUM COUNCIL David J. O’Reilly, Chair Douglas L. Foshee, Vice Chair Marshall W. Nichols, Executive Director U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY Steven Chu, Secretary The National Petroleum Council is a federal advisory committee to the Secretary of Energy. The sole purpose of the National Petroleum Council is to advise, inform, and make recommendations to the Secretary of Energy on any matter requested by the Secretary relating to oil and natural gas or to the oil and gas industries. All Rights Reserved Library of Congress Control Number: 2011944162 © National Petroleum Council 2011 Printed in the United States of America The text and graphics herein may be reproduced in any format or medium, provided they are reproduced accurately, not used in a misleading context, and bear acknowledgement of the National Petroleum Council’s copyright and the title of this report. Outline of Report Materials Summary Report Volume (also available Full Report Volume (printed and available online at www.npc.org) online at www.npc.org) y Report Transmittal Letter to the y Outline of Full Report (see below) Secretary of Energy Additional Study Materials (available online y Outline of Report Materials at www.npc.org) -

Information-Memorandum.Pdf

INFORMATION MEMORANDUM FOR INFORMATION ONLY This document is important. If you are in any doubt as to the action you should take, you should consult your legal, financial, tax or other professional adviser. LISTING BY WAY OF INTRODUCTION OF KRISENERGY LTD. (incorporated with limited liability under the laws of the Cayman Islands) (the “Issuer”) S$130,000,000 Senior Unsecured Notes due 2022 S$200,000,000 Senior Unsecured Notes due 2023 This document (the “Information Memorandum”) is issued in connection with the listing and quotation of the S$130,000,000 Senior Unsecured Notes due 2022 (the “2022 Notes”) and the S$200,000,000 Senior Unsecured Notes due 2023 (the “2023 Notes” and together with the 2022 Notes, the “New Notes”), issued by KrisEnergy Ltd. (the “Issuer”or“KrisEnergy”). The New Notes were initially issued on 11 January 2017 pursuant to extraordinary resolutions of noteholders of the Series 1 S$130,000,000 6.25 per cent. fixed rate notes due 2017 (the “2017 Notes”) and Series 2 S$200,000,000 5.75 per cent. fixed rate notes due 2018 (the “2018 Notes”, and together with the 2017 Notes, the “Existing Notes”), respectively, sanctioning, approving, assenting and agreeing irrevocably to, inter alia, (i) the exchange for the 2017 Notes of the 2022 Notes on the terms and conditions of the 2022 Notes set out and more fully described in this Information Memorandum and the Consent Solicitation Statement (the “2022 Notes Exchange”); and (ii) the exchange for the 2018 Notes of the 2023 Notes on the terms and conditions of the 2023 Notes set out and more fully described in the Consent Solicitation Statement (the “2023 Notes Exchange”, and together with the 2022 Notes Exchange, the “Notes Exchanges”). -

Impacts and Mitigations of in Situ Bitumen Production from Alberta Oil Sands

Impacts and Mitigations of In Situ Bitumen Production from Alberta Oil Sands Neil Edmunds, P.Eng. V.P. Enhanced Oil Recovery Laricina Energy Ltd. Calgary, Alberta Submission to the XXIst World Energy Congress Montréal 2010 - 1 - Introduction: In Situ is the Future of Oil Sands The currently recognized recoverable resource in Alberta’s oil sands is 174 billion barrels, second largest in the world. Of this, about 150 billion bbls, or 85%, is too deep to mine and must be recovered by in situ methods, i.e. from drill holes. This estimate does not include any contributions from the Grosmont carbonate platform, or other reservoirs that are now at the early stages of development. Considering these additions, together with foreseeable technological advances, the ultimate resource potential is probably some 50% higher, perhaps 315 billion bbls. Commercial in situ bitumen recovery was made possible in the 1980's and '90s by the development in Alberta, of the Steam Assisted Gravity Drainage (SAGD) process. SAGD employs surface facilities very similar to steamflooding technology developed in California in the ’50’s and 60’s, but differs significantly in terms of the well count, geometry and reservoir flow. Conventional steamflooding employs vertical wells and is based on the idea of pushing the oil from one well to another. SAGD uses closely spaced pairs of horizontal wells, and effectively creates a melt cavity in the reservoir, from which mobilized bitumen can be collected at the bottom well. Figure 1. Schematic of a SAGD Well Pair (courtesy Cenovus) Economically and environmentally, SAGD is a major advance compared to California-style steam processes: it uses about 30% less steam (hence water and emissions) for the same oil recovery; it recovers more of the oil in place; and its surface impact is modest. -

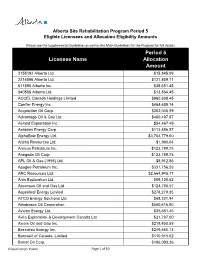

Alberta Site Rehabilitation Program Period 5 Eligible Licensees and Allocation Eligibility Amounts

Alberta Site Rehabilitation Program Period 5 Eligible Licensees and Allocation Eligibility Amounts Please see the Supplemental Guidelines as well as the Main Guidelines for the Program for full details Period 5 Licensee Name Allocation Amount 2155192 Alberta Ltd. $15,845.09 2214896 Alberta Ltd. $121,809.11 611890 Alberta Inc. $35,651.45 840586 Alberta Ltd. $13,864.45 ACCEL Canada Holdings Limited $960,608.45 Conifer Energy Inc. $464,459.14 Acquisition Oil Corp. $302,046.99 Advantage Oil & Gas Ltd. $460,497.87 Aeneid Exploration Inc. $54,467.49 Aeraden Energy Corp. $113,886.57 AlphaBow Energy Ltd. $3,704,779.60 Altima Resources Ltd. $1,980.64 Amicus Petroleum Inc. $123,789.75 Anegada Oil Corp. $123,789.75 APL Oil & Gas (1998) Ltd. $8,912.86 Apogee Petroleum Inc. $331,756.53 ARC Resources Ltd. $2,664,945.71 Artis Exploration Ltd. $89,128.62 Ascensun Oil and Gas Ltd. $124,780.07 Aspenleaf Energy Limited $278,279.35 ATCO Energy Solutions Ltd. $68,331.94 Athabasca Oil Corporation $550,616.80 Avalon Energy Ltd. $35,651.45 Avila Exploration & Development Canada Ltd $21,787.00 Axiom Oil and Gas Inc. $219,850.59 Baccalieu Energy Inc. $249,560.13 Barnwell of Canada, Limited $110,915.62 Barrel Oil Corp. $196,083.36 #Classification: Public Page 1 of 10 Alberta Site Rehabilitation Program Period 5 Eligible Licensees and Allocation Eligibility Amounts Please see the Supplemental Guidelines as well as the Main Guidelines for the Program for full details Period 5 Licensee Name Allocation Amount Battle River Energy Ltd. -

Evolution of Canada's Oil and Gas Industry

Evolution Of Canada’s oil and gas industry A historical companion to Our Petroleum Challenge 7th edition EVOLUTION of Canada’s oil and gas industry Copyright 2004 by the Canadian Centre for Energy Information Writer: Robert D. Bott Editors: David M. Carson, MSc and Jan W. Henderson, APR, MCS Canadian Centre for Energy Information Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2R 0C5 Telephone: (403) 263-7722 Facsimile: (403) 237-6286 Toll free: 1-877-606-4636 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.centreforenergy.com Canadian Cataloguing in Publications Data Main entry under title: EVOLUTION of Canada’s oil and gas industry Includes bibliographical references 1. Petroleum industry and trade – Canada 2. Gas industry – Canada 3. History – petroleum industry – Canada I. Bott, Robert, 1945-II. Canadian Centre for Energy Information ISBN 1-894348-16-8 Readers may use the contents of this book for personal study or review only. Educators and students are permitted to reproduce portions of the book, unaltered, with acknowledgment to the Canadian Centre for Energy Information. Copyright to all photographs and illustrations belongs to the organizations and individuals identified as sources. For other usage information, please contact the Canadian Centre for Energy Information in writing. Centre for Energy The Canadian Centre for Energy Information (Centre for Energy) is a non-profit organization created in 2002 to meet a growing demand for balanced, credible information about the Canadian energy sector. On January 1, 2003, the Petroleum Communication Foundation (PCF) became part of the Centre for Energy. Our educational materials will build on the excellent resources published by the PCF and, over time, cover all parts of the Canadian energy sector from oil, natural gas, coal, thermal and hydroelectric power to nuclear, solar, wind and other sources of energy.