Gustav Klimt in Contemporary Photographs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African Masks

Gustav Klimt Slide Script Pre-slides: Focus slide; “And now, it’s time for Art Lit” Slide 1: Words We Will Use Today Mosaics: Mosaics use many tiny pieces of colored glass, shiny stones, gold, and silver to make intricate images and patterns. Art Nouveau: this means New Art - a style of decorative art, architecture, and design popular in Western Europe and the US from about 1890 to 1910. It’s recognized by flowing lines and curves. Patrons: Patrons are men and women who support the arts by purchasing art, commissioning art, or by sponsoring or providing a salary to an artist so they can continue making art. Slide 2 – Gustav Klimt Gustav Klimt was a master of eye popping pattern and metallic color. Art Nouveau (noo-vo) artists like Klimt used bright colors and swirling, flowing lines and believed art could symbolize something beyond what appeared on the canvas. When asked why he never painted a self-portrait, Klimt said, “There is nothing special about me. Whoever wants to know something about me... ought to look carefully at my pictures.” We may not have a self-portrait but we do have photos of him – including this one with his studio cat! Let’s see what we can learn about Klimt today. Slide 3 – Public Art Klimt was born in Vienna, Austria where he lived his whole life. Klimt’s father was a gold engraver and he taught his son how to work with gold. Klimt won a full scholarship to art school at the age of 14 and when he finished, he and his brothers started a business painting murals on walls and ceilings for mansions, public theatres and universities. -

Download Download

Dreams anD sexuality A Psychoanalytical Reading of Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze benjamin flyThe This essay presenTs a philosophical and psychoanalyTical inTerpreTaTion of The work of The Viennese secession arTisT, GusTaV klimT. The manner of depicTion in klimT’s painTinGs underwenT a radical shifT around The Turn of The TwenTieTh cenTury, and The auThor attempTs To unVeil The inTernal and exTernal moTiVaTions ThaT may haVe prompTed and conTribuTed To This TransformaTion. drawinG from friedrich nieTzsche’s The BirTh of Tragedy as well as siGmund freud’s The inTerpreTaTion of dreams, The arTicle links klimT’s early work wiTh whaT may be referred To as The apollonian or consciousness, and his laTer work wiTh The dionysian or The subconscious. iT is Then arGued ThaT The BeeThoven frieze of 1902 could be undersTood as a “self-porTraiT” of The arTisT and used To examine The shifT in sTylisTic represenTaTion in klimT’s oeuVre. Proud Athena, armed and ready for battle with her aegis Pallas Athena (below), standing in stark contrast to both of and spear, cuts a striking image for the poster announcing these previous versions, takes their best characteristics the inaugural exhibition of the Vienna Secession. As the and bridges the gap between them: she is softly modeled goddess of wisdom, the polis, and the arts, she is a decid- but still retains some of the poster’s two-dimensionality (“a edly appropriate figurehead for an upstart group of diverse concept, not a concrete realization”2); the light in her eyes artists who succeeded in fighting back against the estab- speaks to an internal fire that more accurately represents lished institution of Vienna, a political coup if there ever the truth of the goddess; and perhaps most importantly, 28 was one. -

LESSON Gustav Klimt Elements Of

LESSON 1 Gustav Klimt Elements of Art Tree of Life Verbal Directions LESSON GUSTAV KLIMT/ELEMENTS OF ART 1 KIMBALL ART CENTER & PARK CITY ED. FOUNDATION LESSON OVERVIEW Students will learn about the artist Gustav Klimt (1862–1918) and his SUPPLIES • Images of Klimt’s artwork decorative art style. Klimt was a twentieth century master of decorative showcasing elements of art. art, a visual art style known for hosting design and ornamentation of • Samples of Tree of Life. items. Students will also learn about the elements of art and how they are • Gold glitter. portrayed in Klimt’s artwork. Students will use these elements with verbal • Glue. directives to create their own “Tree of Life”, one of Klimt’s most famous • Black sharpies. works, in his decorative style. • Markers. • Metallic markers and/or INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES paint markers. • Learn about Gustav Klimt. • White or brown paper. • Learn about the elements of art and apply them in artwork. • Black construction paper for Line, Shape, Form, Value, Space, Color, Texture matting artwork. • Learn about Klimt’s decorative style of art. • Create a “Tree of Life” using elements of art in the style of Klimt. GUSTAV KLIMT Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) was an Austrian symbolist painter and his artwork was viewed as a rebellion against the traditional academic art of his time. He is noted for his highly decorative style in art most often seen in art with women with elaborate gowns, blankets and landscapes. Klimt was a co-founder of the Vienna Secessionist movement, a movement closely linked to Symbolism whereby artists tried to show truth using unrealistic or fantastical objects. -

Artist Resources – Gustav Klimt (Austrian, 1862-1918) Gustav Klimt Foundation Klimt at Neue Galerie, New York

Artist Resources – Gustav Klimt (Austrian, 1862-1918) Gustav Klimt Foundation Klimt at Neue Galerie, New York The Getty Center partnered with Vienna’s Albertina Museum in 2012 for the first retrospective dedicated to Klimt’s prolific drawing practice. Marking the 150th anniversary of his birth, the prominent collection traced Klimt’s use of the figure from the 1880s until his death. Digital resources from the Getty provide background on Klimt’s relationships to Symbolism and the Secession movement, his public murals, drawings, and late portraits. In 2015, the Neue Galerie commemorated the film, Woman in Gold, with an exhibition bringing together Klimt’s infamous portrait of Adele Bloch Bauer with a suite of historical material. Bauer’s portrait was at the nexus of a conversation about the return of Nazi looted art, now in prestigious museums, to the progeny of families they were stolen from during WWII. San Francisco’s de Young museum presented the first major exhibition of Klimt’s work on the west coast in 207, paiting the Vienna Secessionist with sculptures and works on paper by August Rodin, whom Klimt met in 1902. The Leopold museum celebrated the centennial of Klimt’s death and his contribution to Viennese modernism in a comprehensive survey in 2018. Also in 2018, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and the Royal Academy of Art in London opened surveys exploring the creative influences of Klimt and his young mentee Egon Schiele through the medium of drawing. Klimt, 1917 In a series of talks in Boston in conjunction with the exhibition, Professor Judith Bookbinder spoke about the aesthetic differences of Klimt, Schiele, and Schiele’s contemporary Oskar Kokoschka. -

The Restitution of a Gustav Klimt Masterpiece

A living memorial to the Holocaust, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum inspires citizens and leaders worldwide to confront hatred, prevent genocide, and promote human dignity. Federal support guarantees the Museum’s permanent place on the National Mall, and its far-reaching educational programs and global impact are made possible by generous donors. Cover: Litzlberg am Attersee, Gustav Klimt, ca. 1914–15. Oil on canvas. From Robbery to Rescue: The Restitution of a Gustav Klimt Masterpiece Northeast Regional Office 60 E. 42nd Street, Suite 2540 New York, NY 10165-0018 ushmm.org Judie and Howard Ganek and Betsy and Doug Korn cordially invite you to a special presentation on behalf of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum From Robbery to Rescue: The Restitution of a Gustav Klimt Masterpiece Join us as Lucian Simmons, Senior Vice President of Sotheby’s and head of its worldwide restitution team, reveals the Featured Speaker Lucian Simmons extraordinary story behind a Gustav Klimt masterpiece Senior Vice President seized by the Nazis and only recently returned to its Provenance and Restitution rightful owner. Sotheby’s Under Nazi occupation, the precious possessions of Jewish families became commodities of the Third Reich. Among these stolen treasures were masterpieces of modern art like Wednesday, October 26 Litzlberg am Attersee, a Klimt landscape now valued at more 6–8 p.m. than $25 million. Acquired by Amalie Redlich from her brother and his wife, the painting was confiscated by the Sotheby’s Gestapo from Amalie’s home near Vienna, Austria, and sold 1334 York Avenue, between 71st and 72nd Streets after she was deported in 1941 to the Lodz ghetto, where New York City she disappeared forever. -

Suspect List in Stolen Klimt Saga Grows

AiA News-Service NEWS ART CRIME Suspect list in stolen Klimt saga grows A woman connected to the museum where the painting was found is under investigation by the Italian police GARETH HARRIS 19th February 2020 12:23 GMT MORE Gustav Klimt's Portrait of a Lady (1916-17) was stolen from the Ricci Oddi Gallery of Modern Art in 1997 The saga of the stolen Gustav Klimt painting discovered within the walls of an Italian museum has taken a new turn after the widow of the institution's former director was taken in for questioning by police. Rossella Tiadina, the widow of Stefano Fugazza, the former director of Ricci Oddi Gallery of Modern Art in the northern Italian city of Piacenza, remains under investigation by the Piacenza police in relation to the robbery, according to a source close to the gallery. No charges have yet been brought but Piacenza police have confirmed Tiadina is under investigation. The work in question Portrait of a Lady (1916-17), which was taken on 22 February 1997 from the gallery, was found by a gardener last December, after they removed a metal plate on an exterior wall of the gallery. The painting was found concealed in a bag buried within a cavity. In early January, officials at the gallery announced that the work has been authenticated and is a genuine work by Klimt valued at €60m. The Ricci Oddi Gallery of Modern Art in Piacenza, Italy The investigation was prompted by an entry in Fugazza’s diary which was first reported by the BBC in 2016. -

Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) Gustav Klimt's Work Is Highly Recognizable

Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) Gustav Klimt’s work is highly recognizable around the world. He has a reputation as being one of the foremost painters of his time. He is regarded as one the leaders in the Viennese Secessionist movement. During his lifetime and up until the mid-twentieth century, Klimt’s work was not known outside the European art world. Gustav Klimt was born on July 14, 1862 in Baumgarten, near Vienna. He was the second child of seven born to a Bohemian engraver of gold and silver. His father’s profession must have rubbed off on his children. Klimt’s brother Georg became a goldsmith, his brother Ernst joined Gustav as a painter. At the age of 14, Klimt went to the School of Arts and Crafts at the Royal and Imperial Austrian Museum for Art and Industry in Vienna along with his brother. Klimt’s training was in applied art techniques like fresco painting, mosaics and the history of art and design. He did not have any formal painting training. Klimt, his brother Ernst and friend Franz Matsch earned a living creating architectural decorations on commission. They worked on villas and theaters and made money on the side by painting portraits. Klimt’s major break came when the trio helped their teacher paint murals in Kunsthistorische Museum in Vienna. His work helped him begin gain the job of painting interior murals and ceilings in large public buildings on the Ringstraße, including a successful series of "Allegories and Emblems". His work on murals in the Burgtheater in Vienna earned him in 1888 a Golden order of Merit by Franz Josef I of Austria and he became an honorary member of the University of Munich and the University of Vienna. -

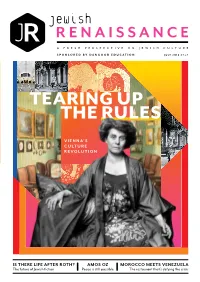

Tearing up the Rules

Jewish RENAISSANCE A FRESH PERSPECTIVE ON JEWISH CULTURE SPONSORED BY DANGOOR EDUCATION JULY 2018 £7.25 TEARING UP THE RULES VIENNA’S CULTURE REVOLUTION IS THERE LIFE AFTER ROTH? AMOS OZ MOROCCO MEETS VENEZUELA The future of Jewish fiction Peace is still possible The restaurant that’s defying the crisis JR Pass on your love of Jewish culture for future generations Make a legacy to Jewish Renaissance ADD A LEGACY TO JR TO YOUR WILL WITH THIS SIMPLE FORM WWW.JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK/CODICIL GO TO: WWW.JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK/DONATIONS FOR INFORMATION ON ALL WAYS TO SUPPORT JR CHARITY NUMBER 1152871 JULY 2018 CONTENTS WWW.JEWISHRENAISSANCE.ORG.UK JR YOUR SAY… Reader’s rants, raves 4 and views on the April issue of JR. WHAT’S NEW We announce the 6 winner of JR’s new arts award; Mike Witcombe asks: is there life after Roth? FEATURE Amos Oz on Israel at 10 70, the future of peace, and Trump’s controversial embassy move. FEATURE An art installation in 12 French Alsace is breathing new life into an old synagogue. NATALIA BRAND NATALIA © PASSPORT Vienna: The writers, 14 artists, musicians and thinkers who shaped modernism. Plus: we speak to the contemporary arts activists working in Vienna today. MUSIC Composer Na’ama Zisser tells Danielle Goldstein about her 30 CONTENTS opera, Mamzer Bastard. ART A new show explores the 1938 32 exhibition that brought the art the Nazis had banned to London. FILM Masha Shpolberg meets 14 34 the director of a 1968 film, which followed a group of Polish exiles as they found haven on a boat in Copenhagen. -

Birth of Modernism

EN OPENING MARCH 16TH BIRTH OF (Details) Wien Museum, © Leopold Werke: Moriz Nähr ÖNB/Wien, Klimt, Weitere Gustav Pf 31931 D (2). MODERNISM PRESS RELEASE VIENNA 1900 BIRTH OF MODERNISM FROM 16TH MARCH 2019 The exhibition Vienna 1900. Birth of Modernism has been conceived as the Leopold Muse- um’s new permanent presentation. It affords insights into the enormous wealth and diver- sity of this era’s artistic and intellectual achievements with all their cultural, social, political and scientific implications. Based on the collection of the Leopold Museum compiled by Ru- dolf Leopold and complemented by select loans from more than 50 private and institutional collections, the exhibition conveys the atmosphere of the former metropolis Vienna in a unique manner and highlights the sense of departure characterized by contrasts prevalent at the turn of the century. The presentation spans three floors and features some 1,300 exhibits over more than 3,000 m2 of exhibition space, presenting a singular variety of media ranging from painting, graphic art, sculpture and photography, via glass, ceramics, metals, GUSTAV KLIMT textiles, leather and jewelry, all the way to items of furniture and entire furnishings of apart- Death and Life, 1910/11, reworked in 1915/16 ments. The exhibition, whose thematic emphases are complemented by a great number of Leopold Museum, Vienna archival materials, spans the period of around 1870 to 1930. Photo: Leopold Museum, Vienna/ Manfred Thumberger UPHEAVAL AND DEPARTURE IN VIBRANT FIN-DE-SIÈCLE VIENNA At the turn of the century, Vienna was the breeding ground for an unprecedentedly fruitful intellectual life in the areas of arts and sciences. -

Students Will Learn About Austrian Artist Gustav Klimt. They Will Then U

Gustav Klimt 3rd Grade Two 45-minute sessions Purpose: Students will learn about Austrian artist Gustav Klimt. They will then use their knowledge about and inspiration from Klimt’s work to create their own abstract collage. Vocabulary: Gustav Klimt, gold leaf, abstract art, line, shape, form, and color Materials: Biographical information about Klimt (attached), Images of Klimt’s work (at least one per four student group), gold paper (either made by painting gold paint on white paper, or by using gold wrapping paper) cut into equal rectangles (one per student), white and black construction paper, permanent markers (blue, orange, green, purple, red, & yellow). Klimt Bio attached Methods: Begin by looking at Gustav Klimt’s work and reading about his life. At this stage, the kids can work in groups and study one of Klimt’s pieces, answering questions about it: What colors does he use? Are his pieces abstract? Are parts of his pieces abstract? What is the subject matter? The students then draw patterns and shapes that they see. *Next, students work in groups of four. A Klimt piece is placed on the table in front of them and they study its contents. Have them focus on what kinds of shapes they see, what kinds of shapes create patterns, what kinds of lines Klimt uses. *Each student is given a piece of gold paper, which will become the base of their artwork. *Looking at the Klimt work, the students pull out important shapes and patterns to copy in their own paintings. Walk around and discuss these images with the groups and give them assignments such as: You see that he uses black and white triangles, now cut these out and place them on your own page. -

Als PDF Herunterladen

Bevor es richtig losging, war eigentlich alles schon vorbei. „… während man denkt, das wären alles nur Vorbereitungen zum Photographiertwerden, bist du schon längst konterfeit. X-mal hat sie geknipst und du hast es nicht gemerkt.“ In ihrer Biografie „Mein Leben mit Alfred Loos“ beschreibt die Wiener Schauspielerin Elsie Altmann-Loos in einem kurzen Kapitel einen Termin im Atelier der Fotografien Dora Kallmus, die sich als d’Ora im Wien des beginnenden 20. Jahrhunderts rasch einen Namen machte. Die Liste der Klientinnen und Klienten der aus bürgerlichem Hause stammenden frühen Karrierefrau (ihr Vater war der jüdische Hof- und Gerichtsadvokat Dr. Philipp Kallmus) liest sich wie ein Who is Who der Wiener High Society. Vom Adelsgeschlecht der Habsburger über literarische Größen wie Arthur Schnitzler und Karl Kraus bis hin zu bekannten Künstlern wie Gustav Klimt und Tänzerinnen wie Anita Berber – kaum jemand, der hierzulande in die Annalen der Geschichte einging, der nicht zumindest ein Mal vor die Kameralinse der Dora Kallmus getreten wäre. Wer schön sein wollte ging zu Madame d’Ora. Das belegt auch ein Brief von Alma Mahler Werfel, in dem es um eine auszuführende Retusche ging. Die talentierte Fotografin war nicht nur ehrgeizig und in technischen Belangen versiert. Neben neuesten Portraittechniken, die sie sich unter anderen im Rahmen eines Praktikums im damals wegweisenden Studio von Nicola Perscheid in Berlin aneignete, wurde ihr zudem ein gutes Maß an Intuition bekundet. Aber auch ihr Geschick, wenn es darum ging, das passende Ambiente zu erzeugen, kam ihr zugute. Bereits ihr Wiener Atelier, im Stile der Wiener Werkstätten eingerichtet, zeugte vom guten Geschmack. -

Gustav Klimt: Painting, Design and Modern Life in Vienna 1900

Tate Liverpool Educators’ Pack Gustav Klimt: Painting, Design and Modern Life in Vienna 1900 Gustav Klimt Fir Forest I 1901 courtesy Kunsthaus Zug, Stiftung Sammlung Kamm The Exhibition at Tate Liverpool As the first comprehensive survey of the work of this artist in the UK, this exhibition at Tate Liverpool focuses on the life and art of Gustav Klimt. The exhibition examines Klimt’s role as founder and leader of the Vienna Secession, a progressive group of artists whose work and philosophy embraced all aspects of arts and craft. It features key works from all stages of the artist’s career alongside fellow Secessionist artists such as Josef Hoffman, Carl Moll, Bruno Reiffenstein, and Koloman Moser. This pack will help educators focus on specific areas of this large-scale exhibition with suggested activities and points for discussion that can be used in the classroom and in the gallery. 1 The Vienna Secession (1897-1939) At the turn of the TTTwentiethTwentieth CenturyCentury,, the city of Vienna was one of Europe’s lleadingeading centrescentres of culture. The rising middle classes sought to free themselves from the past and explore new forms of expression in art, architecture, literature and music. The Vienna Secession was founded in 1897 by a group who had resigned from the Association of Austrian Artists, as a protest against the prevailing conservatism of the traditional Künstlerhaus . The movement represented a separation from the art of the past and the establishment of modernism in Austria. The younger generation sought to bring about a renaissance of arts and crafts, uniting architects, designers, Symbolists, Naturalists and craftsmen, from metalworkers to engravers.