Richmond on the Thames (1896)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Geotrail in Richmond Park

A Geotrail in Richmond Park 1 Richmond Park Geotrail In an urban environment it is often difficult to ‘see’ the geology beneath our feet. This is also true within our open spaces. In Richmond Park there is not much in the way of actual rocks to be seen but it is an interesting area geologically as several different rock types occur there. It is for this reason that the southwest corner has been put forward as a Locally Important Geological Site. We will take clues from the landscape to see what lies beneath. Richmond Park affords fine views to both west and east which will throw a wider perspective on the geology of London. Richmond Park is underlain by London Clay, about 51 million years old. This includes the sandier layers at the top, known as the Claygate beds. The high ground near Kingston Gate includes the Claygate beds but faulting along a line linking Pen Ponds to Ham Gate has allowed erosion on the high ground around Pembroke Lodge. Both high points are capped by the much younger Black Park Gravel, which is only about 400,000 years old, the earliest of the Thames series of terraces formed after the great Anglian glaciation. Younger Thames terrace gravels are also to be found in Richmond Park. Useful maps and guide books The Royal Parks have a printable pdf map of Richmond Park on their website: www.royalparks.org.uk/parks/richmond-park/map-of-richmond-park. Richmond Park from Medieval Pasture to Royal Park by Paul Rabbitts, 2014. Amberley Publishing. -

The Earlier Parks Charles I's New Park

The Creation of Richmond Park by The Monarchy and early years © he Richmond Park of today is the fifth royal park associated with belonging to the Crown (including of course had rights in Petersham Lodge (at “New Park” at the presence of the royal family in Richmond (or Shene as it used the old New Park of Shene), but also the Commons. In 1632 he the foot of what is now Petersham in 1708, to be called). buying an extra 33 acres from the local had a surveyor, Nicholas Star and Garter Hill), the engraved by J. Kip for Britannia Illustrata T inhabitants, he created Park no 4 – Lane, prepare a map of former Petersham manor from a drawing by The Earlier Parks today the “Old Deer Park” and much the lands he was thinking house. Carlile’s wife Joan Lawrence Knyff. “Henry VIII’s Mound” At the time of the Domesday survey (1085) Shene was part of the former of the southern part of Kew Gardens. to enclose, showing their was a talented painter, can be seen on the left Anglo-Saxon royal township of Kingston. King Henry I in the early The park was completed by 1606, with ownership. The map who produced a view of a and Hatch Court, the forerunner of Sudbrook twelfth century separated Shene and Kew to form a separate “manor of a hunting lodge shows that the King hunting party in the new James I of England and Park, at the top right Shene”, which he granted to a Norman supporter. The manor house was built in the centre of VI of Scotland, David had no claim to at least Richmond Park. -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Wednesday Volume 672 26 February 2020 No. 30 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Wednesday 26 February 2020 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2020 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 299 26 FEBRUARY 2020 300 Stephen Crabb: As we prepare to celebrate St David’s House of Commons Day, now is a good moment to celebrate the enormous and excellent progress that has been made in reducing unemployment in Wales. Does my right hon. Friend Wednesday 26 February 2020 agree that what is really encouraging is the fact that the long-term lag between Welsh employment levels and the The House met at half-past Eleven o’clock UK average has now closed, with more people in Wales going out to work than ever before? PRAYERS Simon Hart: I am grateful to my right hon. Friend and constituency neighbour for raising this issue. He will be as pleased as I am that the figures in his own [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] constituency, when compared with 2010, are as good as they are. It is absolutely right that the Government’s job, in collaboration with the Welsh Government if that is necessary, is to ensure we create the circumstances Oral Answers to Questions where that trend continues. He has my absolute assurance that that will be the case. Christina Rees (Neath) (Lab/Co-op): Will the Secretary WALES of State provide the House with specific details on how many people have been affected by the catastrophic flood damage to residential properties and businesses The Secretary of State was asked— across Wales, and exactly how much has been lost to the Universal Credit Welsh economy so far? Simon Hart: I should start by saying that, during the 1. -

Preservation Board

The Preservation of Richmond Park © n 1751, the rangership was granted to King George’s youngest agricultural improvements. Minister Lord John Russell (later Earl Russell) in 1846. which still bears his name. Queen Elizabeth - the army’s famous daughter Princess Amelia. She immediately began to tighten the When a new gate and gate lodge In 1835 when Petersham Lodge Queen Mother) were “Phantom” restrictions on entry. Within 6 weeks of her taking up the post there were required for the Richmond In 1801 King George III decided that Henry Addington, his new Prime came on the market, the Office given White Lodge as reconnaissance Iwas an incident. Gate, the plan by Sir John Soane of Woods and Works purchased their first home after squadron, and (surviving in the Soane Museum in the estate, demolished the very their marriage in 1923. 50 acres in the The annual beating of the bounds of Richmond parish had always London) was submitted to the King decayed house, and restored the They found it too remote south-west required entry into the Park. But the bound-beating party of 1751 in April 1795 and was then marked whole of “Petersham Park” to and rapidly gave it up to of the Park found the usual ladder-stile removed. They entered by a breach in the “as approved by His Majesty”. Richmond Park. A new terrace move into London! were used for wall. Sir John Soane was also walk was made along the top of a large hutted instrumental in transforming the the hillside. Old Lodge had been By then the Park was camp for the “mole catcher’s cottage” into the demolished in 1839-41. -

SYON the Thames Landscape Strategy Review 3 3 7

REACH 11 SYON The Thames Landscape Strategy Review 3 3 7 Landscape Character Reach No. 11 SYON 4.11.1 Overview 1994-2012 • There has been encouraging progress in implementing Strategy aims with the two major estates that dominate this reach, Syon and Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. • Syon has re-established its visual connection with the river. • Kew’s master-planning initiatives since 2002 (when it became a World Heritage Site) have recognised the key importance of the historic landscape framework and its vistas, and the need to address the fact that Kew currently ‘turns its back on the river’. • The long stretch of towpath along the Old Deer Park is of concern as a fl ood risk for walkers, with limited access points to safe routes. • Development along the Great West Road is impacting long views from within Syon Park. • Syon House and grounds: major development plan, including re- instatement of Capability Brown landscape: re-connection of house with river (1997), opening vista to Kew Gardens (1996), re-instatement of lakehead in pleasure grounds, restoration of C18th carriage drive, landscaping of car park • Re-instatement of historic elements of Old Deer Park, including the Kew Meridian, 1997 • Kew Vision, launched, 2008 • Kew World Heritage Site Management Plan and Kew Gardens Landscape Masterplan 2012 • Willow spiling and tree management along the Kew Ha-ha • Invertebrate spiling and habitat creation works Kew Ha-ha. • Volunteer riverbank management Syon, Kew LANDSCAPE CHARACTER 4.11.2 The Syon Reach is bordered by two of the most signifi cant designed landscapes in Britain. Royal patronage at Richmond and Kew inspired some of the initial infl uential works of Bridgeman, Kent and Chambers. -

THE PRINCE of WALES and the DUCHESS of CORNWALL Background Information for Media

THE PRINCE OF WALES AND THE DUCHESS OF CORNWALL Background Information for Media May 2019 Contents Biography .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Seventy Facts for Seventy Years ...................................................................................................... 4 Charities and Patronages ................................................................................................................. 7 Military Affiliations .......................................................................................................................... 8 The Duchess of Cornwall ............................................................................................................ 10 Biography ........................................................................................................................................ 10 Charities and Patronages ............................................................................................................... 10 Military Affiliations ........................................................................................................................ 13 A speech by HRH The Prince of Wales at the "Our Planet" premiere, Natural History Museum, London ...................................................................................................................................... 14 Address by HRH The Prince of Wales at a service to celebrate the contribution -

![Richmond [VA] Whig, January-June 1864 Vicki Betts University of Texas at Tyler, Vbetts@Uttyler.Edu](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4557/richmond-va-whig-january-june-1864-vicki-betts-university-of-texas-at-tyler-vbetts-uttyler-edu-644557.webp)

Richmond [VA] Whig, January-June 1864 Vicki Betts University of Texas at Tyler, [email protected]

University of Texas at Tyler Scholar Works at UT Tyler By Title Civil War Newspapers 2016 Richmond [VA] Whig, January-June 1864 Vicki Betts University of Texas at Tyler, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uttyler.edu/cw_newstitles Recommended Citation Betts, ickV i, "Richmond [VA] Whig, January-June 1864" (2016). By Title. Paper 108. http://hdl.handle.net/10950/756 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Civil War Newspapers at Scholar Works at UT Tyler. It has been accepted for inclusion in By Title by an authorized administrator of Scholar Works at UT Tyler. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RICHMOND [VA] WHIG January - June, 1864 RICHMOND [VA] WHIG, January 1, 1864, p. 2, c. 1 The New Year. "Old Sixty Three" is gone at last, and, this day, young "Sixty Four" steps forward to run his course.—In bidding farewell to the departed year, we cannot repress a mental retrospect of the direful events which have reddened the pages of history since we last penned a New Year's paragraph. Blood, precious blood, has been shed profusely, and we may well be excused for indulging the oft-used simile that the incessant raindrops yesterday were tears over the sorrows which the passing year had brought on the helpless victims of this war. But we will not dwell upon the past. Hope bids us look to the future. The good book says, truly, that "no man knoweth what a day may bring forth." We shall, therefore, not attempt to predict what will take place during the next twelve months. -

Richmond Upon Thames

www.visitrichmond.co.uk 2009 - 04 historic houses 2009 - 08 river thames RICHMOND - 2009 10 open spaces 2009 - 12 museums and galleries UPON 2009 - 14 eating and drinking 2009 - 16 shopping 2009 - 18 worship and remembrance THAMES 2009 - 20 attractions 2009 - 26 map VisitRichmond Guide 2009 2009 - 31 richmond hill 2009 - 32 restaurants and bars 2009 - 36 accommodation and venues 2009 - 48 language schools 2009 - 50 travel information Full page advert --- 2 - visitrichmond.co.uk Hampton Court Garden Welcome to Cllr Serge Lourie London’s Arcadia Richmond upon Thames lies 15 miles in Barnes is an oasis of peace and a southwest of central London yet a fast haven for wildlife close to the heart of train form Waterloo Station will take you the capital while Twickenham Stadium, here in 15 minutes. When you arrive you the home of England Rugby has a will emerge into a different world. fantastic visitors centre which is open all year round. Defi ned by the Thames with over 21 miles of riverside we are without doubt the most I am extremely honoured to be Leader beautiful of the capitals 32 boroughs. It is of this beautiful borough. Our aim at the with good reason that we are known as Town Hall is to preserve and improve it for London’s Arcadia. everyone. Top of our agenda is protecting the environment and fi ghting climate We really have something for everyone. change. Through our various policies Our towns are vibrant and stylish with we are setting an example of what local great places to eat, shop, drink and government can do nationally to ensure a generally have a good time. -

Job 115610 Type

A WONDERFULLY LATERAL FAMILY HOME WITH A STUNNING GARDEN Sudbrook Gardens Richmond TW10 7DD Freehold Sudbrook Gardens Richmond TW10 7DD Freehold generous open living space ◆ kitchen/dining room ◆ media room ◆ laundry room ◆ 5 bedrooms ◆ 3 bathrooms ◆ stunning garden ◆ garage ◆ EPC rating = D Situation Within just two miles of both Richmond and Kingston (with their sophisticated array of shops, restaurants and boutiques) the house nestles idyllically within this much acclaimed cul de sac, directly abutting Richmond Golf Course. Furthermore it is within a few hundred yards of Richmond Park (with its 2300 deer inhabited acres), stunning Ham Common and a particularly scenic stretch of The River Thames - providing a genuinely semi rural atmosphere. Richmond train station offers a direct and rapid service into London Waterloo, as well as the District Underground Tube and overland line to Stratford, via North London. There is a good selection of local shops at Ham Parade, also within just a few hundred yards. Local schools enjoy an excellent reputation and are considered amongst the best in the country. Description Occupying a generous plot that backs directly onto Richmond Golf Course, the house affords fabulous open aspects and excellent natural light. Although it already offers extensive family accommodation (at over 3000 square feet) there is further scope to extend should a buyer require, subject to planning consent. The rooms are well proportioned and laid out, with the superb lateral footprint providing as well for everyday family life as it does for more formal entertaining. The delightful garden is well established and predominantly laid to lawn, with impressive maximum measurements of 125' x 100'. -

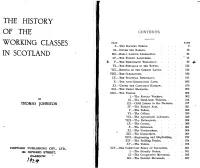

The History of the Working Classes in Scotland

THE HISTORY OF THE CONTENTS. CHAP. WORKING CLASSES I.—THE SLAVERY PERIOD, II.—UNDER THE BARONS, IN SCOTLAND III.—EARLY LABOUR LEGISLATION, IV.—THE FORCED LABOURERS, . $£■ V.—THE DEMOCRATIC THEOCRACY, VI.—THE STRUGGLE IN THE TOWNS, VII.—EEIVING oi" THE COMMON LANDS, VIII.—THE CLEARANCES, IX.—THE POLITICAL DEMOCRACY, X.—THE ANTI-COMBINATION LAWS, XI.—UNDER THE CAPITALIST HARROW, XII.—THE GREAT MASSACRE, XIII.—THE UNIONS, I.—The Factory Workers, BY II.—The Hand-loom Weavers, . THOMAS JOHNSTON III.—Child Labour in the Factories, IV.—The Factory Acts, . V.—The Bakers, VI.-—The Colliers, . VII.—The Agricultural Labourers, VIII.—The Railwaymen, IX.—The Carters, . X.—The Sailormen, XI.—The Woodworkers, XII.—The Ironworkers, XIII.—Engineering and Shipbuilding, XIV.—The Building Trades, XV.—The Tailors, . PORWARD PUBLISHING COY., LTD., XIV.—THE COMMUNIST SEEDS OF SALVATION, I.—The Friendly Orders, 164 HOWARD STREET, II.—The Co-operative Movement, GLASGOW. III.—The Socialist Movement, . tfLf 84 THE HISTORY OF THE WORKING GLASSES. their freedom in the courts, it followed, as a general rule, that the slave was only liberated by death. The result of all these restric CHAPTER V, tions was that coal-mining remained unpopular and the mine-owners in Scotland were still forced to pay higher wages for labour than were THE DEMOCRATIC THEOCRACY. their English confreres. And so the liberating Act of 1799, which " The Solemn League and Covenant finally abolished slavery in the coal mines and saltpans of Scotland, Whiles brings a sigh and whiles a tear; was urged upon Parliament by the more far-seeing coalowners them But Sacred Freedom, too, was there, selves. -

The 1811 Richmond Theatre Fire

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2015 The Fatal Lamp and the Nightmare after Christmas: The 1811 Richmond Theatre Fire Amber Marie Martinez Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/4043 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Amber M. Martinez________________________2015 All Rights Reserved The Fatal Lamp and the Nightmare after Christmas The 1811 Richmond Theatre Fire A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University. by Amber Marie Martinez Bachelor of Fine Arts in Theatre Performance Virginia Commonwealth University, 2009 Director: Dr. Noreen C. Barnes, Director of Graduate Studies, Department of Theatre Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia December 2015 ii Acknowledgement The author wishes to thank several people. I would like to thank my son Faris whose presence inspired me to return to school to obtain a master’s degree. I would like to thank my partner Richard for his love and encouragement during the past few years. I would like to thank my parents for their continuous love and support that has seen me through difficult times. I would also like to thank Dr. Noreen C. Barnes for paving the path to discovering my love for this historical event. -

White Priory Murders

THE WHITE PRIORY MURDERS John Dickson Carr Writing as Carter Dickson CHAPTER ONE Certain Reflections in the Mirror "HUMPH," SAID H. M., "SO YOU'RE MY NEPHEW, HEY?" HE continued to peer morosely over the tops of his glasses, his mouth turned down sourly and his big hands folded over his big stomach. His swivel chair squeaked behind the desk. He sniffed. 'Well, have a cigar, then. And some whisky. - What's so blasted funny, hey? You got a cheek, you have. What're you grinnin' at, curse you?" The nephew of Sir Henry Merrivale had come very close to laughing in Sir Henry Merrivale's face. It was, unfortu- nately, the way nearly everybody treated the great H. M., including all his subordinates at the War Office, and this was a very sore point with him. Mr. James Boynton Bennett could not help knowing it. When you are a young man just arrived from over the water, and you sit for the first time in the office of an eminent uncle who once managed all the sleight-of-hand known as the British Military Intelligence Department, then some little tact is indicated. H. M., although largely ornamental in these slack days, still worked a few wires. There was sport, and often danger, that came out of an unsettled Europe. Bennett's father, who was H. M.'s brother-in-law and enough of a somebody at Washington to know, had given him some extra-family hints before Bennett sailed. "Don't," said the elder Bennett, "don't, under any circumstances, use any ceremony with him.