The Ethical Implications for Humans in Light of the Poor Predictive Value of Animal Models

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consideration of Alternatives to the Use of Live Animals for Research and Teaching

Division of Laboratory Animal Resources Consideration of Alternatives to the Use of Live Animals For Research and Teaching From the ETSU Animal Study Protocol form: The search for alternatives refers to the three Rs described in the book, The Principles of Humane Experimental Technique (1959) by Russell and Burch. The 3Rs are reduction in the number of animals used, refinement of techniques and procedures to reduce pain or distress, and replacement of animals with non-animal techniques or use of less-sentient species. Refinement: The use of analgesics and analgesia, the use of remote telemetry to increase the quality and quantity of data gathered, and humane endpoints for the animals are examples of refinements. Reduction: The use of shared control groups, preliminary screening in non-animal systems, innovative statistical packages or a consultation with a statistician are examples of reduction alternatives. Replacement: Alternatives such as in vitro, cell culture, tissue culture, models, simulations, etc. are examples of replacement. This is also where you might look for any non-mammalian animal models—fish or invertebrates, for example—that would still give you the data you need. The AWIC (Animal Welfare Information Center) recommends alternative searches be performed in 2 phases. Phase 1 considers reduction and refinement and the recommendation is NOT to use the word "alternative" unless the particular area of research happens to be an area in which there has been considerable work in developing alternatives (e.g. Toxicology and education). This phase should get after no unnecessary duplication, appropriate animal numbers, the best pain-relieving agents and other methods that may serve to minimize or limit pain and distress. -

Cruelty Free International

Cruelty Free International Sector: Household and Personal Care Region: Based in the United Kingdom, operates globally Cruelty Free International certifies brands producing cosmetics, personal care, household and cleaning products that do all they can to remove animal testing from their supply chains ('cruelty- free') and comply with the Leaping Bunny certification criteria. Cruelty Free International’s sustainability claim is the Leaping Bunny logo on products, which aims to allow shoppers to make more informed choices. Cruelty Free International and its partners have, so far, certified over 1000 brands around the world. Mindset Life Cycle Thinking: The claim focuses on the product manufacturing stage (i.e. the relevant phase where animal testing would occur). A supplier monitoring system must be implemented to monitor the claim, to ensure that the brand has not carried out, commissioned or been party to experiments on animals during the manufacturing of a product throughout its supply chain (including its raw materials and ingredients), whilst an independent and rigorous audit is conducted within the first 12 months of certification, and then every three years. Hotspots Analysis Approach: As a single-issue certification scheme, Cruelty Free International does not aim to assess all relevant impacts of the products it certifies and has therefore not undertaken a hotspots analysis. Cruelty Free International focuses on monitoring and enforcing high cruelty free standards throughout a brand’s manufacturing of a product. Mainstreaming Sustainability: Cruelty Free International encourages certified brands to apply the cruelty free logic to other products in their portfolio. Partnerships with ethical and cruelty free brands are also designed to support a brand's external sustainability and advocacy strategies and internal objectives. -

Innovative Delivery of Sirna to Solid Tumors by Super Carbonate Apatite

RESEARCH ARTICLE Innovative Delivery of siRNA to Solid Tumors by Super Carbonate Apatite Xin Wu1,2, Hirofumi Yamamoto1*, Hiroyuki Nakanishi3, Yuki Yamamoto3, Akira Inoue1, Mitsuyoshi Tei1, Hajime Hirose1, Mamoru Uemura1, Junichi Nishimura1, Taishi Hata1, Ichiro Takemasa1, Tsunekazu Mizushima1, Sharif Hossain4,5, Toshihiro Akaike4,5, Nariaki Matsuura6, Yuichiro Doki1, Masaki Mori1 1 Department of Surgery, Gastroenterological Surgery, Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka University, Suita, Japan, 2 Research Fellow of Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Tokyo, Japan, 3 Nakanishi Gastroenterological Research Institute, Sakai, Japan, 4 Department of Biomolecular Engineering, Graduate School of Bioscience and Biotechnology, Tokyo Institute of Technology, Yokohama, Japan, 5 Biomaterials Center for Regenerative Medical Engineering, Foundation for Advancement of International Science, Tsukuba, Japan, 6 Osaka Medical Center for Cancer and Cardiovascular Diseases, Osaka, Japan * [email protected] Abstract RNA interference (RNAi) technology is currently being tested in clinical trials for a limited OPEN ACCESS number of diseases. However, systemic delivery of small interfering RNA (siRNA) to solid tumors has not yet been achieved in clinics. Here, we introduce an in vivo pH-sensitive de- Citation: Wu X, Yamamoto H, Nakanishi H, livery system for siRNA using super carbonate apatite (sCA) nanoparticles, which is the Yamamoto Y, Inoue A, Tei M, et al. (2015) Innovative Delivery of siRNA to Solid Tumors by Super smallest class of nanocarrier. These carriers consist simply of inorganic ions and accumu- Carbonate Apatite. PLoS ONE 10(3): e0116022. late specifically in tumors, yet they cause no serious adverse events in mice and monkeys. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0116022 Intravenously administered sCA-siRNA abundantly accumulated in the cytoplasm of tumor Academic Editor: Sung Wan Kim, University of cells at 4 h, indicating quick achievement of endosomal escape. -

The Animal Welfare Act at Fifty: Problems and Possibilities in Animal Testing Regulation

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons McGeorge School of Law Scholarly Articles McGeorge School of Law Faculty Scholarship 2016 The Animal Welfare Act at Fifty: Problems and Possibilities in Animal Testing Regulation Courtney G. Lee Pacifc McGeorge School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/facultyarticles Part of the Animal Law Commons Recommended Citation Courtney G. Lee, The Animal Welfare Act at Fifty: Problems and Possibilities in Animal Testing Regulation, 95 Neb. L. Rev. 194 (2016). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the McGeorge School of Law Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in McGeorge School of Law Scholarly Articles by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Courtney G. Lee* The Animal Welfare Act at Fifty: Problems and Possibilities in Animal Testing Regulation TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction .......................................... 195 II. Background of the Animal Welfare Act ................ 196 A. Enactment and Evolution.......................... 196 B. Early Amendments ................................ 197 C. Improved Standards for Laboratory Animals Act of 1985 .............................................. 198 D. Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees .... 201 E. IACUC Effectiveness .............................. 203 III. Coverage of the AWA .................................. 205 A. What Is an “Animal” under the AWA? ............. -

The Case Against Animal Experiments

The Case Against Animal Experiments Animal experiments are both unethical and unscientific. Animals in laboratories endure appalling suffering, such as being deliberately poisoned, brain-damaged and subjected to inescapable electric shocks. The pain and misery inflicted on the victims is enough, on its own, to make vivisection worthy of public condemnation. But animal “ “ experiments are also bad science, since the results they produce cannot be reliably translated to humans. They therefore offer little hope of advancing medical progress. The Case Against Animal Experiments outlines the suffering of animals used in research, before providing a clear, non-technical description of the scientific problems S E with vivisection. L I www.animalaid.org.uk C I N I M O D © How animals are used Contents Each year around four million How animals are used .......................... 1 animals are experimented on inside British laboratories. The suffering of animals in Dogs, cats, horses, monkeys, laboratories ........................................ 2 rats, rabbits and other animals Cruel experiments .................................... 2 are used, as well as hundreds A failing inspection regime ........................ 3 of thousands of genetically Secrecy and misinformation ...................... 4 modified mice. The most The GM mouse myth ................................ 4 common types of experiment The scientific case against either attempt to test how animal experiments .............................. 5 safe a substance is (toxicity Summary ............................................... -

The Use of Animals for Research in the Pharmaceutical Industry

Chapter 8 The use of animals for research in the pharmaceutical industry The ethics of research involving animals The use of animals for research in the CHAPTER 8 pharmaceutical industry Introduction THE USE OF ANIMALS FOR RESEARCH IN PHARMACEUTICAL INDUSTRY 8.1 The pharmaceutical industry conducts or supports approximately one third of the animal research that is undertaken in the UK. Some of this is basic research that seeks to examine normal biological processes and the nature of disease (see also Chapters 5 and 6). However, most has more specific, applied objectives and concerns the development of new medicines or vaccines, improved diagnosis or better methods of toxicity testing. Since the process of producing medicines has changed significantly over time, we begin with a brief overview of developments from the late 19th century to the present. We then describe the way medicines are currently produced in terms of eight stages. These are: discovery and selection of compounds that could be effective medicines (stages 1 and 2), characterisation of promising candidate medicines (stages 3 and 4), selecting candidate medicines and ensuring their safety (stage 5), clinical studies on humans (stages 6 to 8), and also research carried out to support the medicine once it has been marketed. For each stage we describe the way in which animals are used in the process, and give some examples of specific experiments. As in the case of research described in the previous chapters, welfare implications for the animals involved in pharmaceutical research are as diverse as the types of research and must be considered on a case by case basis. -

The Abandonment and Neglect of Hunting Dogs Jamie B

Exigence Volume 2 | Issue 1 Article 5 2018 Hunting a Home: The Abandonment and Neglect of Hunting Dogs Jamie B. Walker Germanna Community College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.vccs.edu/exigence Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Natural Resources Law Commons, and the Other Animal Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Walker, J. B. (2018). Hunting a Home: The Abandonment and Neglect of Hunting Dogs. Exigence, 2 (1). Retrieved from https://commons.vccs.edu/exigence/vol2/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ VCCS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Exigence by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ VCCS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walker: Hunting a Home Introduction Hailed as an Old Dominion tradition reaching back to the English roots of the Virginia Colony, hunting with dogs seems to be as popular today as it was when George Washington participated in the 18th Century. Rabbit, fox, racoon and pheasant, to name a few, are easiest to catch or kill with the assistance of man’s best friend and her magnificent nose, and over the years deer hunting with dogs climbed to the top of the popularity list for canine sportsmen. While many lament the fate of the quarry, there exists a victim nearer to the hunter than even the deer: his dogs. Mistreatment of these working animals has been widely reported in the media (Telvock, 2013), but rarely studied in academic circles. What can be done to improve the lot of the Virginia hunting hound without squeezing the rights of the humane hunters which traditionally reach all the way back to England? Ironically, England may hold the key. -

Frequently Asked Questions

Frequently Asked Questions What Types of Companies Are on the "Don't Test" List? This list includes companies that make cosmetics, personal-care products, household-cleaning products, and other common household products. All companies that are included on PETA's "don't test" list have signed our statement of assurance verifying that they and their ingredient suppliers don't conduct, commission, pay for, or allow any tests on animals for ingredients, formulations, or finished products anywhere in the world and will not do so in the future. We encourage consumers to support the companies on this list, since we know that they're committed to making products without harming animals. Companies on the "Do Test" list should be shunned until they implement a policy that prohibits animal testing. The "do test" list doesn't include companies that manufacture only products that are required by law to be tested on animals (e.g., pharmaceuticals and garden chemicals). Although PETA is opposed to all animal testing, our focus in those instances is less on the individual companies and more on the regulatory agencies that require animal testing. How Does a Company Get on PETA's Global Animal Test–Free List? In order to be listed as animal test–free by PETA's Beauty Without Bunnies program, a company or brand must submit a legally binding statement of assurance signed by its CEO verifying that it and its ingredient suppliers don't conduct, commission, pay for, or allow any tests on animals for ingredients, formulations, or finished products anywhere in the world and won't do so in the future. -

Cruelty Free International – Written Evidence (JTN0008)

Cruelty Free International – Written Evidence (JTN0008) 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Cruelty Free International is a UK-based organisation working to end animal experiments worldwide. With a history of over 100 years, our science, regulatory and legal experts work with authorities in the UK, the EU and around the world to advance humane and human-relevant science. Cruelty Free International also runs the Leaping Bunny approval programme for brands committed to cruelty free cosmetics, personal care and household products and works with hundreds of UK companies from small to large. In 2018, we delivered eight million petition signatures to the United Nations together with The Body Shop in support of a global end to the use of animals in cosmetics testing. Summary A UK-Japan free trade agreement is an opportunity for the UK government to put into action its verbal commitment to enhancing animal protection now that the country has left the European Union (EU). As our Prime Minister said in a debate in the House of Commons on 10th June 2020: “Not only will we protect animal welfare standards but, on leaving the EU, as we have, we will be able to increase our animal welfare standards.” In 1998, the UK was the first country to place restrictions in law on animal testing for cosmetics. Currently, there are no such restrictions in Japan where, for ordinary use cosmetics, it is for companies to decide which methods of testing they use and where, for so-called special use cosmetics, it is mandatory to test new ingredients on animals. In our view, any UK-Japan free trade agreement should explicitly state that the UK will not accept reliance on safety data derived from animal tests for the import of any cosmetics, whether ordinary or special use, into the UK from Japan – even if this is already the effect of the relevant UK law. -

Read the 2020 Annual Report

2020 Annual Report ACHIEVEMENTS FOR ANIMALS The Humane Society of the United States and Humane Society International work together to end the cruelest practices toward animals, rescue and care for animals in crisis, and build a stronger animal protection movement. And we can’t do it without you. How we work Ending the cruelest practices We are focused on ending the worst forms of institutionalized animal suffering— including extreme confinement of farm animals, puppy mills, the fur industry, trophy hunting, animal testing of cosmetics and the dog meat trade. Our progress is the result of our work with governments, the private sector and multinational bodies; public awareness and consumer education campaigns, public policy efforts, and more. Caring for animals in crisis We respond to large-scale cruelty cases and disasters around the world, providing rescue, hands-on care, logistics and expertise when animals are caught in crises. Our affiliated care centers heal and provide lifelong sanctuary to abused, abandoned, exploited, vulnerable and neglected animals. Building a stronger animal protection movement Through partnerships, trainings, support, collaboration and more, we’re building a more humane world by empowering and expanding the capacity of animal welfare advocates and organizations in the United States and across the globe. Together, we’ll bring about faster change for animals. Our Animal Rescue and Response team stands ready 24/7 to help animals caught in crises in the United States and around the world. Here, HSI director of global animal disaster response Kelly Donithan comforts a koala we saved after the devastating wildfires on Australia’s Kangaroo Island. -

Animals Are Suffering: HSUS Seeks to End Rabbit Blinding Tests

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 3-1980 Animals are Suffering: HSUS Seeks to End Rabbit Blinding Tests Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/cu_reps Part of the Animal Experimentation and Research Commons, Animal Studies Commons, and the Other Business Commons Recommended Citation "Animals are Suffering: HSUS Seeks to End Rabbit Blinding Tests" (1980). Close Up Reports. 10. https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/cu_reps/10 This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. w J: 1- CLOSE-U ANIMALS Annually, 65 to 100 million animals are being used as test subjects in the laboratories of cosmetic companies, drug manu facturers, university and commercial research centers, and pro AR,E ducers of household products. The Humane Society of the United States has taken the position that much of this test SUFFERING~ ing is not only unreliable, but also results in unnecessary pain and death. HSUS seeks to end Cats, dogs, birds, rats, mice, monkeys, and rabbits are rabbit blinding tests just some of the animals routinely subjected to electric shocks, rubber riot control bullets, huge doses of radiation, and chemical solutions. The research industry has long held that the use of animals is the only "reliable" way we have of determining the safety of a cosmetic, drug, or household product. Over the years this belief has served to support scientists as they subjected ani- mals to many tests. The American public has seen little of the massive animal suffering that has taken place in the research labs. -

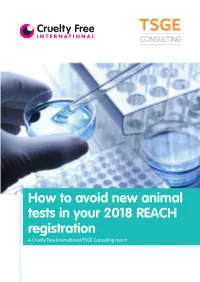

How to Avoid New Animal Tests in Your 2018 REACH Registration a Cruelty Free International/TSGE Consulting Report Contents

How to avoid new animal tests in your 2018 REACH registration A Cruelty Free International/TSGE Consulting report Contents 03 Executive summary 04 Introduction 05 New possibilities to avoid animal testing 06 Skin sensitisation 08 Skin corrosion/irritation 10 Serious eye damage/irritation 12 Acute toxicity 13 Short term toxicity in fish 14 Key points to avoid unnecessary animal testing 16 If animal testing cannot be avoided 17 Dealing with compliance checks 18 Further information 2 How to avoid new animal tests in your 2018 REACH registration Executive summary Do you need to register your chemicals for REACH 2018? Are you assisting companies in their registrations? Are you looking at what information is required to fulfil REACH registration requirements? Might you be involved in commissioning new tests if they are required? Then this guide is for you! Since REACH was adopted in 2006 there have been some significant developments in alternative methods to animal testing. Several methods have now been approved that can fully replace some animal tests and there are new waiving approaches for others. There are changes to the REACH legal text as well as ECHA guidance that cover these new options. In order to help companies avoid testing on animals we have produced this simple guide to signpost you to these recent changes. If you have any questions please don’t hesitate to get in touch. Cruelty Free International Cruelty Free International is the leading organisation working to create a world where nobody wants or believes we need to experiment on animals. We are widely respected as an authority on animal testing issues and are frequently called on by governments, the media, corporations and official bodies for advice or expert opinion.