THE LOGIC of QUANTIFIED STATEMENTS Outline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CSE Yet, Please Do Well! Logical Connectives

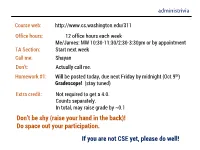

administrivia Course web: http://www.cs.washington.edu/311 Office hours: 12 office hours each week Me/James: MW 10:30-11:30/2:30-3:30pm or by appointment TA Section: Start next week Call me: Shayan Don’t: Actually call me. Homework #1: Will be posted today, due next Friday by midnight (Oct 9th) Gradescope! (stay tuned) Extra credit: Not required to get a 4.0. Counts separately. In total, may raise grade by ~0.1 Don’t be shy (raise your hand in the back)! Do space out your participation. If you are not CSE yet, please do well! logical connectives p q p q p p T T T T F T F F F T F T F NOT F F F AND p q p q p q p q T T T T T F T F T T F T F T T F T T F F F F F F OR XOR 푝 → 푞 • “If p, then q” is a promise: p q p q F F T • Whenever p is true, then q is true F T T • Ask “has the promise been broken” T F F T T T If it’s raining, then I have my umbrella. related implications • Implication: p q • Converse: q p • Contrapositive: q p • Inverse: p q How do these relate to each other? How to see this? 푝 ↔ 푞 • p iff q • p is equivalent to q • p implies q and q implies p p q p q Let’s think about fruits A fruit is an apple only if it is either red or green and a fruit is not red and green. -

Conditional Statement/Implication Converse and Contrapositive

Conditional Statement/Implication CSCI 1900 Discrete Structures •"ifp then q" • Denoted p ⇒ q – p is called the antecedent or hypothesis Conditional Statements – q is called the consequent or conclusion Reading: Kolman, Section 2.2 • Example: – p: I am hungry q: I will eat – p: It is snowing q: 3+5 = 8 CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 1 CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 2 Conditional Statement/Implication Truth Table Representing Implication (continued) • In English, we would assume a cause- • If viewed as a logic operation, p ⇒ q can only be and-effect relationship, i.e., the fact that p evaluated as false if p is true and q is false is true would force q to be true. • This does not say that p causes q • If “it is snowing,” then “3+5=8” is • Truth table meaningless in this regard since p has no p q p ⇒ q effect at all on q T T T • At this point it may be easiest to view the T F F operator “⇒” as a logic operationsimilar to F T T AND or OR (conjunction or disjunction). F F T CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 3 CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 4 Examples where p ⇒ q is viewed Converse and contrapositive as a logic operation •Ifp is false, then any q supports p ⇒ q is • The converse of p ⇒ q is the implication true. that q ⇒ p – False ⇒ True = True • The contrapositive of p ⇒ q is the –False⇒ False = True implication that ~q ⇒ ~p • If “2+2=5” then “I am the king of England” is true CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 5 CSCI 1900 – Discrete Structures Conditional Statements – Page 6 1 Converse and Contrapositive Equivalence or biconditional Example Example: What is the converse and •Ifp and q are statements, the compound contrapositive of p: "it is raining" and q: I statement p if and only if q is called an get wet? equivalence or biconditional – Implication: If it is raining, then I get wet. -

Logical Connectives Good Problems: March 25, 2008

Logical Connectives Good Problems: March 25, 2008 Mathematics has its own language. As with any language, effective communication depends on logically connecting components. Even the simplest “real” mathematical problems require at least a small amount of reasoning, so it is very important that you develop a feeling for formal (mathematical) logic. Consider, for example, the two sentences “There are 10 people waiting for the bus” and “The bus is late.” What, if anything, is the logical connection between these two sentences? Does one logically imply the other? Similarly, the two mathematical statements “r2 + r − 2 = 0” and “r = 1 or r = −2” need to be connected, otherwise they are merely two random statements that convey no useful information. Warning: when mathematicians talk about implication, it means that one thing must be true as a consequence of another; not that it can be true, or might be true sometimes. Words and symbols that tie statements together logically are called logical connectives. They allow you to communicate the reasoning that has led you to your conclusion. Possibly the most important of these is implication — the idea that the next statement is a logical consequence of the previous one. This concept can be conveyed by the use of words such as: therefore, hence, and so, thus, since, if . then . , this implies, etc. In the middle of mathematical calculations, we can represent these by the implication symbol (⇒). For example 3 − x x + 7y2 = 3 ⇒ y = ± ; (1) r 7 x ∈ (0, ∞) ⇒ cos(x) ∈ [−1, 1]. (2) Converse Note that “statement A ⇒ statement B” does not necessarily mean that the logical converse — “statement B ⇒ statement A” — is also true. -

2-2 Statements, Conditionals, and Biconditionals

2-2 Statements, Conditionals, and Biconditionals Use the following statements to write a 3. compound statement for each conjunction or SOLUTION: disjunction. Then find its truth value. Explain your reasoning. is a disjunction. A disjunction is true if at least p: A week has seven days. one of the statements is true. q is false, since there q: There are 20 hours in a day. are 24 hours in a day, not 20 hours. r is true since r: There are 60 minutes in an hour. there are 60 minutes in an hour. Thus, is true, 1. p and r because r is true. SOLUTION: ANSWER: p and r is a conjunction. A conjunction is true only There are 20 hours in a day, or there are 60 minutes when both statements that form it are true. p is true in an hour. since a week has seven day. r is true since there are is true, because r is true. 60 minutes in an hour. Then p and r is true, 4. because both p and r are true. SOLUTION: ANSWER: ~p is a negation of statement p, or the opposite of A week has seven days, and there are 60 minutes in statement p. The or in ~p or q indicates a an hour. p and r is true, because p is true and r is disjunction. A disjunction is true if at least one of the true. statements is true. ~p would be : A week does not have seven days, 2. which is false. q is false since there are 24 hours in SOLUTION: a day, not 20 hours in a day. -

New Approaches for Memristive Logic Computations

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 6-6-2018 New Approaches for Memristive Logic Computations Muayad Jaafar Aljafar Portland State University Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Electrical and Computer Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Aljafar, Muayad Jaafar, "New Approaches for Memristive Logic Computations" (2018). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4372. 10.15760/etd.6256 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. New Approaches for Memristive Logic Computations by Muayad Jaafar Aljafar A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Electrical and Computer Engineering Dissertation Committee: Marek A. Perkowski, Chair John M. Acken Xiaoyu Song Steven Bleiler Portland State University 2018 © 2018 Muayad Jaafar Aljafar Abstract Over the past five decades, exponential advances in device integration in microelectronics for memory and computation applications have been observed. These advances are closely related to miniaturization in integrated circuit technologies. However, this miniaturization is reaching the physical limit (i.e., the end of Moore’s Law). This miniaturization is also causing a dramatic problem of heat dissipation in integrated circuits. Additionally, approaching the physical limit of semiconductor devices in fabrication process increases the delay of moving data between computing and memory units hence decreasing the performance. The market requirements for faster computers with lower power consumption can be addressed by new emerging technologies such as memristors. -

Immediate Inference

Immediate Inference Dr Desh Raj Sirswal, Assistant Professor (Philosophy) P.G. Govt. College for Girls, Sector-11, Chandigarh http://drsirswal.webs.com . Inference Inference is the act or process of deriving a conclusion based solely on what one already knows. Inference has two types: Deductive Inference and Inductive Inference. They are deductive, when we move from the general to the particular and inductive where the conclusion is wider in extent than the premises. Immediate Inference Deductive inference may be further classified as (i) Immediate Inference (ii) Mediate Inference. In immediate inference there is one and only one premise and from this sole premise conclusion is drawn. Immediate inference has two types mentioned below: Square of Opposition Eduction Here we will know about Eduction in details. Eduction The second form of Immediate Inference is Eduction. It has three types – Conversion, Obversion and Contraposition. These are not part of the square of opposition. They involve certain changes in their subject and predicate terms. The main concern is to converse logical equivalence. Details are given below: Conversion An inference formed by interchanging the subject and predicate terms of a categorical proposition. Not all conversions are valid. Conversion grounds an immediate inference for both E and I propositions That is, the converse of any E or I proposition is true if and only if the original proposition was true. Thus, in each of the pairs noted as examples either both propositions are true or both are false. Steps for Conversion Reversing the subject and the predicate terms in the premise. Valid Conversions Convertend Converse A: All S is P. -

Introduction to Logic CIS008-2 Logic and Foundations of Mathematics

Introduction to Logic CIS008-2 Logic and Foundations of Mathematics David Goodwin [email protected] 11:00, Tuesday 15th Novemeber 2011 Outline 1 Propositions 2 Conditional Propositions 3 Logical Equivalence Propositions Conditional Propositions Logical Equivalence The Wire \If you play with dirt you get dirty." Propositions Conditional Propositions Logical Equivalence True or False? 1 The only positive integers that divide 7 are 1 and 7 itself. 2 For every positive integer n, there is a prime number larger than n. 3 x + 4 = 6. 4 Write a pseudo-code to solve a linear diophantine equation. Propositions Conditional Propositions Logical Equivalence True or False? 1 The only positive integers that divide 7 are 1 and 7 itself. True. 2 For every positive integer n, there is a prime number larger than n. True 3 x + 4 = 6. The truth depends on the value of x. 4 Write a pseudo-code to solve a linear diophantine equation. Neither true or false. Propositions Conditional Propositions Logical Equivalence Propositions A sentence that is either true or false, but not both, is called a proposition. The following two are propositions 1 The only positive integers that divide 7 are 1 and 7 itself. True. 2 For every positive integer n, there is a prime number larger than n. True whereas the following are not propositions 3 x + 4 = 6. The truth depends on the value of x. 4 Write a pseudo-code to solve a linear diophantine equation. Neither true or false. Propositions Conditional Propositions Logical Equivalence Notation We will use the notation p : 2 + 2 = 5 to define p to be the proposition 2 + 2 = 5. -

Logic, Proofs

CHAPTER 1 Logic, Proofs 1.1. Propositions A proposition is a declarative sentence that is either true or false (but not both). For instance, the following are propositions: “Paris is in France” (true), “London is in Denmark” (false), “2 < 4” (true), “4 = 7 (false)”. However the following are not propositions: “what is your name?” (this is a question), “do your homework” (this is a command), “this sentence is false” (neither true nor false), “x is an even number” (it depends on what x represents), “Socrates” (it is not even a sentence). The truth or falsehood of a proposition is called its truth value. 1.1.1. Connectives, Truth Tables. Connectives are used for making compound propositions. The main ones are the following (p and q represent given propositions): Name Represented Meaning Negation p “not p” Conjunction p¬ q “p and q” Disjunction p ∧ q “p or q (or both)” Exclusive Or p ∨ q “either p or q, but not both” Implication p ⊕ q “if p then q” Biconditional p → q “p if and only if q” ↔ The truth value of a compound proposition depends only on the value of its components. Writing F for “false” and T for “true”, we can summarize the meaning of the connectives in the following way: 6 1.1. PROPOSITIONS 7 p q p p q p q p q p q p q T T ¬F T∧ T∨ ⊕F →T ↔T T F F F T T F F F T T F T T T F F F T F F F T T Note that represents a non-exclusive or, i.e., p q is true when any of p, q is true∨ and also when both are true. -

Logic, Sets, and Proofs David A

Logic, Sets, and Proofs David A. Cox and Catherine C. McGeoch Amherst College 1 Logic Logical Statements. A logical statement is a mathematical statement that is either true or false. Here we denote logical statements with capital letters A; B. Logical statements be combined to form new logical statements as follows: Name Notation Conjunction A and B Disjunction A or B Negation not A :A Implication A implies B if A, then B A ) B Equivalence A if and only if B A , B Here are some examples of conjunction, disjunction and negation: x > 1 and x < 3: This is true when x is in the open interval (1; 3). x > 1 or x < 3: This is true for all real numbers x. :(x > 1): This is the same as x ≤ 1. Here are two logical statements that are true: x > 4 ) x > 2. x2 = 1 , (x = 1 or x = −1). Note that \x = 1 or x = −1" is usually written x = ±1. Converses, Contrapositives, and Tautologies. We begin with converses and contrapositives: • The converse of \A implies B" is \B implies A". • The contrapositive of \A implies B" is \:B implies :A" Thus the statement \x > 4 ) x > 2" has: • Converse: x > 2 ) x > 4. • Contrapositive: x ≤ 2 ) x ≤ 4. 1 Some logical statements are guaranteed to always be true. These are tautologies. Here are two tautologies that involve converses and contrapositives: • (A if and only if B) , ((A implies B) and (B implies A)). In other words, A and B are equivalent exactly when both A ) B and its converse are true. -

1 Deductive Reasoning and Logical Connectives

Propositional Logic CS/Math231 Discrete Mathematics Spring 2015 1 Deductive Reasoning and Logical Connectives As we have seen, proofs play a central role in mathematics and they are based on deductive reasoning. Facts (or statements) can be represented using Boolean variables, i.e., the values of variables can only be true or false but not both. Definition 1 A statement (or proposition) is a sentence that is true or false but not both. Example 1 Examples of deductive reasoning: 1. I will have dinner either with Jody or with Ann. Jody is out of town. Therefore, I will have dinner with Ann. 2. If today is Wednesday, then I have to go to class. Today is Wednesday. Therefore, I have to go to class. 3. All classes are held either on Mondays and Wednesdays or on Tuesdays and Thursdays. There is no Discrete Math course on Tuesdays. Therefore, Discrete Math course is held on Mondays and Wednesdays. Definition 2 (premises and conclusion) A conclusion is arrived from assumptions that some state- ments, called premises, are true. An argument being valid means that if the premises are all true, then the conclusion is also true. Example 2 An example of an invalid deductive reasoning: Either 1+1=3 or 1+1=5. It is not the case that 1+1=3. Therefore, 1+1=5. p _ q p or q :p not p ) q Therefore, q If p and q are statement variables, then complicated logical expressions (compound statements) related to p and q can be built from logical connectives. -

Hilog: a Foundation for Higher-Order Logic Programming

J. LOGIC PROGRAMMING 1993:15:187-230 187 HILOG: A FOUNDATION FOR HIGHER-ORDER LOGIC PROGRAMMING WEIDONG CHEN,* MICHAEL KIFER, AND DAVID S. WARREN D We describe a novel logic, called HiLog, and show that it provides a more suitable basis for logic programming than does traditional predicate logic. HiLog has a higher-order syntax and allows arbitrary terms to appear in places where predicates, functions, and atomic formulas occur in predicate calculus. But its semantics is first-order and admits a sound and complete proof procedure. Applications of HiLog are discussed, including DCG grammars, higher-order and modular logic programming, and deductive databases. a 1. PREFACE Manipulating predicates, functions, and even atomic formulas is commonplace in logic programming. For example, Prolog combines predicate calculus, higher-order, and meta-level programming in one working system, allowing programmers routine use of generic predicate definitions (e.g., transitive closure, sorting) where predi- cates can be passed as parameters and returned as values [7]. Another well-known useful feature is the “call” meta-predicate of Prolog. Applications of higher-order constructs in the database context have been pointed out in many works, including [24, 29, 411. Although predicate calculus provides the basis for Prolog, it does not have the wherewithal to support any of the above features, which, consequently, have an ad hoc status in logic programming. In this paper, we investigate the fundamental principles underlying higher-order logic programming and, in particular, shed new light on why and how these Prolog features appear to work in practice. We propose *Present address: Computer Science and Engineering, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, TX 75275. -

Why the Converse Consequence Condition Cannot Be Accepted LUCA MORETTI

Why the Converse Consequence Condition cannot be accepted LUCA MORETTI Three general confirmation principles discussed by Hempel (1965) are the following: Converse Consequence Condition (CCC) If an observation statement E confirms a hypothesis H and if another hypothesis H* entails H, then E confirms H*. Special Consequence Condition (SCC) If an observation statement E confirms a hypothesis H, then E confirms any of H’s logical conse- quences. Entailment Condition (EC) If an observation statement E entails an- other statement E*, then E confirms E*. Since the conjunction of the above three principles entails the para- doxical consequence that any observation statement confirms any hy- pothesis (see Le Morvan 1999: 449), Hempel notoriously chose to pre- serve (SCC) and (EC), while rejecting (CCC). Yet, as Le Morvan (1999) has pointed out, one could think of preserving (CCC) by rejecting either (a) both (EC) and (SCC) or (b) only (EC) or (c) only (SCC). In fact, in none of these alternatives does the condition entailing the paradox ap- pear satisfied. Trying to save (CCC) is not pointless since, as Glymour has emphasised, the Converse Consequence Condition ‘has had an undying popularity, and attempts to make it work still continue’ (Glymour 1980: 30). Le Morvan (1999) has however argued that, when the choice among general confirmation principles is just about (CCC), (SCC) and (EC), since none of the three alternatives (a)-(c) is actually acceptable, it is (CCC) that must be rejected. In this paper, I aim to strengthen this argu- ment and to make it definitive. To begin with, according to Le Morvan, since both (EC) and (SCC) are quite intuitive, the alternative (a), which imposes the rejection of both of them, ‘may strike many as a too high price to pay’ (1999: 450), and thus is scarcely acceptable.