Fitzgerald River National Park Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fitzgerald Coast Ravensthorpe * Hopetoun * Munglinup Fitzgerald River National Park 2016

FITZGERALD COAST RAVENSTHORPE * HOPETOUN * MUNGLINUP FITZGERALD RIVER NATIONAL PARK 2016 1 Welcome FITZGERALD COAST RAVENSTHORPE * HOPETOUN * MUNGLINUP FITZGERALD RIVER NATIONAL PARK 2016 Welcome Hamersley sand dunes – Fitzgerald River National Park ! Photo - Josh Brunner Welcome to the 2016 issue of the Fitzgerald Coast Tourism Associations’ Visitor’s Guide. This publication has been designed to ensure that visitors to our wonderful region have all the information they need. It is packed full of what to see, what to do, where to go and how to make the absolute most of your amazing Fitzgerald Coast adventure holiday. www.fitzgeraldcoast.com.au Contents Welcome 2 Our region 3 5-day self drive tour 4 - 6 Range 4WD tour guide 7 - 8 Ravensthorpe Range 9 Farm Gate Art Trail 10 - 11 Ravensthorpe History 12 Ravensthorpe 13 FRNP map 14 – 15 Walk trails 16 Wildflowers and plants 17 Hopetoun 18 – 19 Fitzgerald River National Park (FRNP) 20 – 21 Munglinup 22 Camping 23 Sunset over Ravensthorpe Ethel Daw Scenic Drive 24 Photo – John Carlisle Business listing 25 Acknowledgements: Accommodation, meals Produced by: Fitzgerald Coast Tourism Association (FCTA). and business services 26 – 28 Printed by: Abbott & Co, Kewdale WA – Ph: 08 9353 1166 Designed by: Kay Pearson – Ph: 0400 499 267 Advertising sales: [email protected] Disclaimer: Every effort has been made to Photography: Josh Brunner, John Carlisle, Rose Pearson, ensure the information contained within this booklet is correct at the time of publishing. FCTA TourismWA, Dene Bingham, Alan Carmichael. holds no responsibility for incorrect content or information within this publication. 2 Published September 2015 2 Our region — Fitzgerald Coast — Fitzgerald Our region Our region – Fitzgerald Coast Quoin Head – Fitzgerald River National Park – courtesy TourismWA Come and enjoy a temperate Mediterranean The coastal town of Hopetoun has for many climate with beautiful sunny winter days and years served as a retirement village and cool summer nights. -

History and Management of Culham Inlet, a Coastal Salt Lake in South-Western Australia

JournalJournal of ofthe the Royal Royal Society Society of Westernof Western Australia, Australia, 80(4), 80:239-247, December 1997 1997 History and management of Culham Inlet, a coastal salt lake in south-western Australia E P Hodgkin 86 Adelma Road, Dalkeith, WA 6009 email: [email protected] Manuscript received August 1996; accepted May 1997. Abstract When Culham Inlet was first flooded by the Holocene rise in sea level it was an estuary, but in historic times it has been a salt lake closed by a high sea bar. It is in an area of low rainfall and episodic river flow and sometimes all water is lost by evaporation to below sea level. With above average rainfall in 1989 and 1992, high water levels in the Inlet flooded farm paddocks and threatened to break the bar and a road along it from Hopetoun to the Fitzgerald River National Park. In 1993 the bar was breached to release flood water, and the Inlet was briefly an estuary. Engineering measures designed to restore road access and prevent flooding are examined for their potential to restore the Inlet to its pre-1993 condition of a productive ecosystem. Recent clearing in the catchments of Culham Inlet and nearby estuaries in the south coast low rainfall area has increased river flow to them and appears to have caused their bars to break more frequently. Introduction (Fig 2) that is only known to have broken naturally once, In historic times Culham Inlet has been a coastal in 1849. The bar was broken artificially in 1920, but for lagoon on a semi-arid part of the south coast of Western over 70 years since then the Inlet has absorbed river flow Australia (Fig 1), separated from the sea by a high bar without the bar breaking, until 1993. -

Adec Preview Generated PDF File

Rec. West. Aust. Mus., 1976,4 (2) THE GENUS MENETIA (LACERTILIA, SCINCIDAE) IN WESTERN AUSTRALIA G.M. STORR* [Received 1 July 1975. Accepted 1 October 1975. Published 30 September 1976.] ABSTRACT The Australian genus Menetia comprises at least five species, three of which occur in Western Australia, namely M. greyii Gray, M. maini novo and M. surda novo A lectotype is designated for M. greyii. INTRODUCTION Until recently all skinks with an immovable transparent lower eyelid were placed in Ablepharus. Fuhn (1969) broke up this polyphyletic assemblage, allotting the Australian species to nine groups, including the genus Menetia. Fuhn, and indeed all workers till now, regarded Menetia as monotypic. Greer (1974) believes that Menetia is derived from the genus Carlia. All the material used in this revision is lodged in the Western Australian Museum. Genus Menetia Gray Menetia Gray, 1845, 'Catalogue of the specimens of lizards in the collection ofthe British Museum', p.65. Type-species (by monotypy): M. greyii Gray. * Curator of Birds and Reptiles, W.A. Museum. 189 Diagnosis Very small, smooth, terrestrial skinks with lower eyelid immovable and bearing a large circular transparent disc incompletely surrounded by granules; digits 4 + 5; first supraocular long and narrow and obliqu~ly orientated. Distribution Most of Australia except the wettest and coolest regions. At least five species, three of them in Western Australia. Description Snout-vent length up to 38 mm. Tail fragile, 1.2-2.0 times as long as snout to vent. Nasals usually separated widely. No supranasals or postnasals. Prefrontals usually separated very narrowly. Frontal small, little if any larger than prefrontals. -

Great South West Edge Touring Route Drive One of Australia’S Most Fascinating Landscapes Between Perth and Esperance, Known As the Great South West Edge

Drive GREAT SOUTH WEST the EDGE EXPERIENCE WESTERN AUSTRALIA’S EXTRAORDINARY LANDSCAPE, IN ONE GREAT ROAD TRIP ALONG THE EDGE. PERTH THE WONDERS OF WA IN ONE GREAT ROAD TRIP 11 day Great South West Edge Touring Route Drive one of Australia’s most fascinating landscapes between Perth and Esperance, known as the Great South West Edge. This unique region comprises many contrasting landscapes; from ancient mountain ranges and rugged granite headlands along the south coast, to the towering karri trees in the Southern Forests and a network of spectacular caves further to the west. The regions’ best attractions are dotted in and around pretty country towns and vast national parks harbouring some of the world’s most unique flora and fauna. This 11 day attraction itinerary gives visitors the option of covering the full route in an action packed 11 days. Optional detour Kalgoorlie routes are included which can extend your trip to accommodate individual travel Coolgardie times. If time is restricted, visitors can select sections of the itinerary to complete or plan Southern Cross to incorporate air travel, with airports in GREAT EASTERN HWY Kambalda Albany and Esperance to reduce travel time. Merredin This 11 day itinerary can easily be extended Northam to cover a longer period as there is so GREAT EASTERN HWY much to see and do along the route. York Perth Fremantle Armadale Y W H Corrigin Norseman HW Y Y W Brookton INDIAN OCEAN H Hyden H Mandurah T North Dandalup U O S Pinjarra H Kulin W Y Yalgorup Waroona National Park Narrogin Williams Harvey -

Inventory of Taxa for the Fitzgerald River National Park

Flora Survey of the Coastal Catchments and Ranges of the Fitzgerald River National Park 2013 Damien Rathbone Department of Environment and Conservation, South Coast Region, 120 Albany Hwy, Albany, 6330. USE OF THIS REPORT Information used in this report may be copied or reproduced for study, research or educational purposed, subject to inclusion of acknowledgement of the source. DISCLAIMER The author has made every effort to ensure the accuracy of the information used. However, the author and participating bodies take no responsibiliy for how this informrion is used subsequently by other and accepts no liability for a third parties use or reliance upon this report. CITATION Rathbone, DA. (2013) Flora Survey of the Coastal Catchments and Ranges of the Fitzgerald River National Park. Unpublished report. Department of Environment and Conservation, Western Australia. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to thank many people that provided valable assistance and input into the project. Sarah Barrett, Anita Barnett, Karen Rusten, Deon Utber, Sarah Comer, Charlotte Mueller, Jason Peters, Roger Cunningham, Chris Rathbone, Carol Ebbett and Janet Newell provided assisstance with fieldwork. Carol Wilkins, Rachel Meissner, Juliet Wege, Barbara Rye, Mike Hislop, Cate Tauss, Rob Davis, Greg Keighery, Nathan McQuoid and Marco Rossetto assissted with plant identification. Coralie Hortin, Karin Baker and many other members of the Albany Wildflower society helped with vouchering of plant specimens. 2 Contents Abstract .............................................................................................................................. -

Search / Rescue

SEARCH / RESCUE FESA provides a variety of search and rescue services, primarily in support of the Western Australia Police Service. These range from operation of the state’s only dedicated emergency rescue helicopter service to marine search and rescue, in addition to a recently- enhanced capability to deal with casualties of terrorist activities. CONTENTS AERIAL RESCUE 67 CLIFF AND CAVE RESCUE 70 LAND AND AIR SEARCH 72 MARINE SEARCH AND RESCUE 74 ROAD CRASH RESCUE 78 URBAN SEARCH AND RESCUE 80 66 FESA ANNUAL REPORT 2005-2006 Aerial rescue RAC Rescue 1 is Western Australia’s only dedicated emergency rescue helicopter. The service provides: • Emergency rescues, eg. For the victims of car crashes, cliff rescues, farming accidents • Ship to shore rescues including responding to Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacons • Hospital transfers for critically ill patients. PREPAREDNESS RAC Rescue 1 and its highly trained crew are on standby, ready to fly 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. The helicopter is crewed by a pilot, rescue crewman (both supplied under contract by CHC Helicopters Australia) and a St John Ambulance Critical Care Paramedic. Stationed at Jandakot Airport, Perth, RAC Rescue 1 typically operates within a 200km radius, covering 90% of Western Australia’s population or 1.8 million people. The Emergency Rescue Helicopter Service is managed by FESA and is funded by the State Government and principal sponsor, the Royal Automobile Club of Western Australia (RAC). Call outs are usually initiated by, or through St John Ambulance, or at the request of the WA Police. Critical life-saving missions take precedence over any other call out. -

Port Related Structures on the Coast of Western Australia

Port Related Structures on the Coast of Western Australia By: D.A. Cumming, D. Garratt, M. McCarthy, A. WoICe With <.:unlribuliuns from Albany Seniur High Schoul. M. Anderson. R. Howard. C.A. Miller and P. Worsley Octobel' 1995 @WAUUSEUM Report: Department of Matitime Archaeology, Westem Australian Maritime Museum. No, 98. Cover pholograph: A view of Halllelin Bay in iL~ heyday as a limber porl. (W A Marilime Museum) This study is dedicated to the memory of Denis Arthur Cuml11ing 1923-1995 This project was funded under the National Estate Program, a Commonwealth-financed grants scheme administered by the Australian HeriL:'lge Commission (Federal Government) and the Heritage Council of Western Australia. (State Govenlluent). ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Heritage Council of Western Australia Mr lan Baxter (Director) Mr Geny MacGill Ms Jenni Williams Ms Sharon McKerrow Dr Lenore Layman The Institution of Engineers, Australia Mr Max Anderson Mr Richard Hartley Mr Bmce James Mr Tony Moulds Mrs Dorothy Austen-Smith The State Archive of Westem Australia Mr David Whitford The Esperance Bay HistOIical Society Mrs Olive Tamlin Mr Merv Andre Mr Peter Anderson of Esperance Mr Peter Hudson of Esperance The Augusta HistOIical Society Mr Steve Mm'shall of Augusta The Busselton HistOlical Societv Mrs Elizabeth Nelson Mr Alfred Reynolds of Dunsborough Mr Philip Overton of Busselton Mr Rupert Genitsen The Bunbury Timber Jetty Preservation Society inc. Mrs B. Manea The Bunbury HistOlical Society The Rockingham Historical Society The Geraldton Historical Society Mrs J Trautman Mrs D Benzie Mrs Glenis Thomas Mr Peter W orsley of Gerald ton The Onslow Goods Shed Museum Mr lan Blair Mr Les Butcher Ms Gaye Nay ton The Roebourne Historical Society. -

V:\GIS3-Systems\Op Mapping

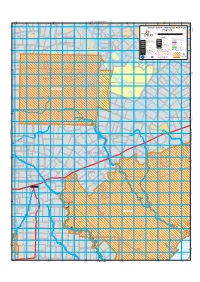

118°50'00"E 119°10'00"E 670 000mE 680 000mE 119°00'00"E 690 000mE 700 000mE Joins Dragon Rocks 710 000mE R 20350 119°20'00"E 720 000mE 730 000mE 119°30'00"E 740 000mE R 20350 R 48436 33°20'00"S Western Shield - 1080 Poison Risk Areas Dunn Rock NR Dunn Rock NR 6 310 000mN 6 310 000mN R 36445 FitzgeraldR 36445 R 20349 Map current as at March 2014 33°20'00"S kilometres 0 2 4 6 8 10 kilometres Lake Bryde NR* A 29020 HORIZONTAL DATUM : GEOCENTRIC DATUM OF AUSTRALIA 1994 (GDA94) - ZONE 50 Dunn Rock NR R 36445 Lake Bryde NR* Shire of Lake Grace A 29021 WHEATBELT LEGEND Department - Managed Land Other Land Categories Management boundaries (includes existing and proposed) Other Crown reserves Shire of State forest, timber reserve, Local Government Authority boundary miscellaneous reserves and land held under title by the CALM Executive Body REGION *Unallocated Crown land (UCL) DPaW region boundary Great Southern National park District *Unmanaged Crown reserves (UMR) DPaW district boundary (not vested with any authority) Nature reserve Trails Private property, Pastoral leases Bibbulmun Track Conservation park Munda Biddi Trail (cycle) Lake Magenta NR R 25113 Cape to Cape Walk Track CALM Act sections 5(1)(g), 5(1)(h) reserve *The management and administration of UCL and UMR's by & miscellaneous reserve DPaW and the Department of Lands respectively, is agreed to by the parties in a Memorandum of Understanding. Western Shield Former leasehold & CALM Act sections DPaW has on-ground management responsibilty. -

South Coast Region Regional Management Plan

SOUTH COAST REGION REGIONAL MANAGEMENT PLAN 1992 - 2002 MANAGEMENT PLAN NO. 24 Department of Conservation and Land Management for the National Parks and Nature Conservation Authority and the Lands and Forest Commission Western Australia PREFACE Regional management plans are prepared by the Department of Conservation and Land Management on behalf of the Lands and Forest Commission and the National Parks and Nature Conservation Authority. These two bodies submit the plans for final approval and modification, if required, by the Minister for the Environment. Regional plans are to be prepared for each of the 10 regions administered by the Department of Conservation and Land Management (CALM). This plan for the South Coast Region covers all lands and waters in the Region vested under the CALM Act, together with wildlife responsibilities included in the Wildlife Conservation Act. In addition to the Regional Plan, more detailed management plans will be prepared for certain critical management issues, (the most serious of which is the spread of dieback disease in the Region); particular high value or high conflict areas, (such as some national parks); or for certain exploited or endangered species, (such as kangaroos and the Noisy Scrub-bird). These plans will provide more detailed information and guidance for management staff. The time frame for this Regional Plan is ten years, although review and restatement of some policies may be necessary during this period. Implementation will take place progressively over this period and there will be continuing opportunity for public comment. This management plan was submitted by the Department of Conservation and Land Management and adopted by the Lands and Forest Commission on 12 June 1991 and the National Parks and Nature Conservation Authority on 19 July 1991 and approved by the Minister for the Environment on 23 December 1991. -

WA Parks Foundation 2018 Annual Report

2018 Annual Report Connecting People to Parks Walpole Nornalup National Park Photo by B. Anderson Message from our Chair The WA Parks Foundation’s second year of operation has been an important year of consolidation and growth. We have continued to embed strong governance, while developing new and beneficial partnerships and initiating planned projects dedicated to enriching our Parks1 and encouraging people to connect with the natural environment. I am delighted to welcome three new Founding our natural environment and increasing appreciation Partners, Chevron Australia, Fortescue Metals Group and of the importance of Western Australia’s parks and Woodside Energy now joining our first Founding Partner, conservation estate. Wesfarmers. In pledging their support our Founding Partners have demonstrated their commitment to The Foundation hopes to increase our sense of the environment. Their support is vital to the ongoing stewardship of our Parks, and the need to conserve and operation of the Foundation and I would like to connect with these wonderful areas, as well as the desire particularly thank our four Founding Partners. to preserve them for future generations. Just being in nature has many benefits and we can all gain both A priority for the Foundation is the revitalisation plan physically and mentally from connecting with the for Western Australia’s first national park, John Forrest. natural environment. We are working with the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA) to conserve and I’d like to express my sincere appreciation and gratitude protect the rich flora, fauna and the cultural and historic to our Board and Committee members, our staff, Parks values of the Park while providing more interpretation Ambassadors and our members, donors, supporters and and an improved visitor experience. -

Impact of Environmental Changes on the Fish Faunas of Western Australian South-Coast Estuaries

Impact of environmental changes on the fish faunas of Western Australian south-coast estuaries Hoeksema, S.D., Chuwen, B.M, Hesp, S.A., Hall, N.G. and Potter, I.C. Project No. 2002/017 Fisheries Research and Development Corporation Report 1 Impact of environmental changes on the fish faunas of Western Australian south-coast estuaries Hoeksema S.D. Chuwen B.M. Hesp S.A. Hall N.G. Potter I.C. March 2006 Centre for Fish and Fisheries Research Murdoch University Murdoch, Western Australia 6150 Copyright Fisheries Research and Development Corporation and Centre for Fish and Fisheries Research 2005 This work is copyright. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), no part of this publication may be reproduced by any process, electronic or otherwise, without the specific written permission of the copyright owners. Neither may information be stored electronically in any form whatsoever without such permission. The Fisheries Research and Development Corporation plans, invests in and manages fisheries research and development throughout Australia. It is a statutory authority within the portfolio of the federal Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, jointly funded by the Australian Government and the fishing industry. March 2006 ISBN: 86905-879-7 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS NON TECHNICAL SUMMARY................................................................................................................................6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.........................................................................................................................................9 -

Adec Preview Generated PDF File

Records of tile Western Australian Museum 21: 111-127 (2002). Western Australian Triplectidinae (Trichoptera: Leptoceridae): descriptions of the female of Triplectides niveipennis and larvae belonging to four genera Rosalind M. St Clair Environment Protection Authority, Freshwater Sciences, GPO Box 439500 Melbourne 3001, Victoria, Australia email: [email protected] Abstract - Larvae of Condocerus aphiS, Notoperata tenax, Symphitoneuria wheeleri, Triplectides niveipennis, and Triplectides en thesis are described for the first time. The female of Triplectides niveipennis is also described for the first time. Variation in larvae and adults of Triplectides niveipennis is discussed, together with unusual characters in the larvae requiring redefinition of the genus. Minor changes to the generic descriptions of Condocerus, Notoperata and Symphitoneuria are also made. INTRODUCTION specimens are available to resolve problems at this Leptoceridae is a major family of Trichoptera in time. The larvae are unusual and require Western Australia, being both diverse and common. redefinition of the genus. The adult leptocerid fauna of Western Australia is Most specimens examined were collected moderately well known, due largely to the efforts during the Land and Water Resources Research of Arthur Neboiss (1982). The Monitoring River Development Corporation funded Monitoring Health Program has resulted in large numbers of River Health Program and material is to be specimens of larvae available for study to augment lodged in the Western Australian Museum. Site distribution data based on adults. These data data for this material start with MUR for sites indicate three leptocerid faunas in Western sampled by Murdoch University, CALM for Australia; one in the cooler wetter south west, one Department of Conservation and Land in the large rivers of the north, and one in the dry Management, ECU for Edith Cowan University areas with little permanent fresh water.