The Private War of Anthony Shaffer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cryptography

Cryptography From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search "Secret code" redirects here. For the Aya Kamiki album, see Secret Code. German Lorenz cipher machine, used in World War II to encrypt very-high-level general staff messages Cryptography (or cryptology; from Greek κρυπτός, kryptos, "hidden, secret"; and γράφ, gráph, "writing", or -λογία, -logia, respectively)[1] is the practice and study of hiding information. Modern cryptography intersects the disciplines of mathematics, computer science, and engineering. Applications of cryptography include ATM cards, computer passwords, and electronic commerce. Cryptology prior to the modern age was almost synonymous with encryption, the conversion of information from a readable state to nonsense. The sender retained the ability to decrypt the information and therefore avoid unwanted persons being able to read it. Since WWI and the advent of the computer, the methods used to carry out cryptology have become increasingly complex and its application more widespread. Alongside the advancement in cryptology-related technology, the practice has raised a number of legal issues, some of which remain unresolved. Contents [hide] • 1 Terminology • 2 History of cryptography and cryptanalysis o 2.1 Classic cryptography o 2.2 The computer era • 3 Modern cryptography o 3.1 Symmetric-key cryptography o 3.2 Public-key cryptography o 3.3 Cryptanalysis o 3.4 Cryptographic primitives o 3.5 Cryptosystems • 4 Legal issues o 4.1 Prohibitions o 4.2 Export controls o 4.3 NSA involvement o 4.4 Digital rights management • 5 See also • 6 References • 7 Further reading • 8 External links [edit] Terminology Until modern times cryptography referred almost exclusively to encryption, which is the process of converting ordinary information (plaintext) into unintelligible gibberish (i.e., ciphertext).[2] Decryption is the reverse, in other words, moving from the unintelligible ciphertext back to plaintext. -

What Role for the Cia's General Counsel

Sed Quis Custodiet Ipsos Custodes: The CIA’s Office of General Counsel? A. John Radsan* After 9/11, two officials at the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) made decisions that led to major news. In 2002, one CIA official asked the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) to clarify how aggressive CIA interrogators could be in questioning al Qaeda operatives held overseas.1 This request led to the August 2002 memorandum, later leaked, in which John Yoo argued that an interrogator crosses the line into torture only by inflicting pain on a par with organ failure.2 Yoo further suggested that interrogators would have many defenses, justifications, and excuses if they faced possible criminal charges.3 One commentator described the advice as that of a “mob lawyer to a mafia don on how to skirt the law and stay out of prison.”4 To cool the debate about torture, the Bush administration retracted the memorandum and replaced it with another.5 The second decision was made in 2003, when another CIA official asked the Justice Department to investigate possible misconduct in the disclosure to the media of the identity of a CIA employee. The employee was Valerie Plame, a covert CIA analyst and the wife of Ambassador Joseph Wilson. * Associate Professor of Law, William Mitchell College of Law. The author was a Justice Department prosecutor from 1991 until 1997, and Assistant General Counsel at the Central Intelligence Agency from 2002 until 2004. He thanks Paul Kelbaugh, a veteran CIA lawyer in the Directorate of Operations, for thoughtful comments on an early draft, and Erin Sindberg Porter and Ryan Check for outstanding research assistance. -

Intelligence System

The U.S. Intelligence System https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OFIG6k4B3zg What is Intelligence? Intelligence – information that meets needs of policy makers and has been collected and processed to meet those needs; all intelligence is information, not all information is intelligence National Intelligence – three subjects -foreign, domestic, and homeland security Intelligence is – a process, product, and a form of organization The Development of U.S. Intelligence National intelligence – didn’t exist until about 1940 CHRONOLOGY -1940-41 – COI (Coordinator of Info) -OSS (Office of Strategic Services) -1941 – Pearl Harbor –mirror imaging/lack of info sharing -1947 – National Security Act – conveyed the legal basis for the intel community; created the SECDEF & National Security Council -cold war influence- countering Soviet Union & stopping the growth of communism -1972- ABM Treaty & SALT I Accord National Technical Means- satellites & other technical collectors (used to verify adherence) Verification- to ensure treaty agreements are honored Monitoring- the means for verification 1975-1976 – created congressional oversight committees ‘cos of violations of law and intel abuses 1989-1991- failure to foresee Soviet collapse (intel failure); minimized Soviet threat 2001- 911 attacks; Patriot Act- allows greater latitude regarding domestic intel gathering Render- delivery of suspected terrorists to a 3rd country that can incarcerate & interrogate with fewer limitations Key judgments- the primary findings of an overall intel estimate that can be -

Book Reviews

Journal of Strategic Security Volume 3 Number 1 Volume 3, No. 1: March 2010 Article 8 Book Reviews Timothy Hsia Sheldon Greaves Donald J. Goldstein Henley-Putnam University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss Part of the Defense and Security Studies Commons, National Security Law Commons, and the Portfolio and Security Analysis Commons pp. 71-78 Recommended Citation Hsia, Timothy; Greaves, Sheldon; and Goldstein, Donald J.. "Book Reviews." Journal of Strategic Security 3, no. 1 (2010) : 71-78. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.3.1.7 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss/vol3/iss1/8 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Strategic Security by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Book Reviews This book review is available in Journal of Strategic Security: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss/ vol3/iss1/8 Hsia et al.: Book Reviews Book Reviews The History of Camp Tracy: Japanese WWII POWs and the Future of Strategic Interrogation. By Alexander D. Corbin. Fort Belvoir, VA: Ziedon Press, 2009. ISBN: 978-0-578-02979- 5. Maps. Photographs. Notes. Bibliography. Index. Pp. 189. $15.95. The History of Camp Tracy, which received the Joint Chiefs of Staff His- tory Office's Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz Archival Research Award, is an illuminating and educating read. The book is written by Alexander Corbin, an intelligence officer in the U.S. -

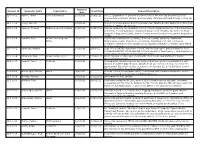

Requests Report

Received Request ID Requester Name Organization Closed Date Request Description Date 12-F-0001 Vahter, Tarmo Eesti Ajalehed AS 10/3/2011 3/19/2012 All U.S. Department of Defense documents about the meeting between Estonian president Arnold Ruutel (Ruutel) and Secretary of Defense Richard Cheney on July 19, 1991. 12-F-0002 Jeung, Michelle - 10/3/2011 - Copies of correspondence from Congresswoman Shelley Berkley and/or her office from January 1, 1999 to the present. 12-F-0003 Lemmer, Thomas McKenna Long & Aldridge 10/3/2011 11/22/2011 Records relating to the regulatory history of the following provisions of the Department of Defense Federal Acquisition Regulation Supplement (DFARS), the former Defense Acquisition Regulation (DAR), and the former Armed Services Procurement Regulation (ASPR). 12-F-0004 Tambini, Peter Weitz Luxenberg Law 10/3/2011 12/12/2011 Documents relating to the purchase, delivery, testing, sampling, installation, Office maintenance, repair, abatement, conversion, demolition, removal of asbestos containing materials and/or equipment incorporating asbestos-containing parts within its in the Pentagon. 12-F-0005 Ravnitzky, Michael - 10/3/2011 2/9/2012 Copy of the contract statement of work, and the final report and presentation from Contract MDA9720110005 awarded to the University of New Mexico. I would prefer to receive these documents electronically if possible. 12-F-0006 Claybrook, Rick Crowell & Moring LLP 10/3/2011 12/29/2011 All interagency or other agreements with effect to use USA Staffing for human resources management. 12-F-0007 Leopold, Jason Truthout 10/4/2011 - All documents revolving around the decision that was made to administer the anti- malarial drug MEFLOQUINE (aka LARIAM) to all war on terror detainees held at the Guantanamo Bay prison facility as stated in the January 23, 2002, Infection Control Standard Operating Procedure (SOP). -

Hidden Arena: Cyber Competition and Conflict in Indo-Pacific Asia James Lewis Prepared for the Lowy Institute Macarthur Asia Security Project

Hidden Arena: Cyber Competition and Conflict in Indo-Pacific Asia James Lewis Prepared for the Lowy Institute MacArthur Asia Security Project Executive summary Cyber infrastructure is critical to the global economy. Yet it is badly secured, worse governed, and a place of interstate competition and potential conflict. There is widespread concern among states over strategic competition in cyberspace, including cyber espionage and cyber attack. Asia, with its political tensions, vigorous economies, and lack of strong multilateral institutions, is a focal point for this competition. The rise of China and its extensive cyber capabilities defines strategic competition in both Asia and in cyberspace globally. The cyber domain is better understood in terms of competition than of war. The possession of advanced cyber attack capabilities has tended to instill caution in nations. Still, because of the newness of technology, lack of agreement on norms, and potential to mistake cyber espionage for military action, cyber competition can increase risks of miscalculation, conflict and escalation during wider interstate tension. The strategic cyber challenge in Asia should be addressed in multiple ways. Cooperation in cyber defence between the United States and its allies can proceed in tandem with greater efforts at US-China dialogue and reassurance. Cooperative approaches worth pursuing include agreement on norms for responsible state behavior in cyberspace and reaching common agreement on the applicability of international laws of war in cyberspace. Overview The internet shrinks distance and make borders more porous. It is part of a set of new technologies that form a man-made environment called cyberspace. Cyberspace connects nations more closely than ever before. -

A Rational Choice Reflection on the Balance Among Individual Rights, Collective Security, and Threat Portrayals Between 9/11 and the Invasion of Iraq Robert Bejesky

Barry Law Review Volume 18 Article 2 Issue 1 Fall 2012 2012 A Rational Choice Reflection on the Balance Among Individual Rights, Collective Security, and Threat Portrayals Between 9/11 and the Invasion of Iraq Robert Bejesky Follow this and additional works at: https://lawpublications.barry.edu/barrylrev Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the National Security Law Commons Recommended Citation Robert Bejesky (2012) "A Rational Choice Reflection on the Balance Among Individual Rights, Collective Security, and Threat Portrayals Between 9/11 and the Invasion of Iraq," Barry Law Review: Vol. 18 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://lawpublications.barry.edu/barrylrev/vol18/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Barry Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Barry Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Barry Law. : A Rational Reflection A RATIONAL CHOICE REFLECTION ON THE BALANCE AMONG INDIVIDUAL RIGHTS, COLLECTIVE SECURITY, AND THREAT PORTRAYALS BETWEEN 9/11 AND THE INVASION OF IRAQ Robert Bejesky* I. Introduction....................................31 II. Balancing Collective Security and Civil Liberties..... ..... 32 III. Threat Warnings............................36 IV. A More Sober Risk Calculation......................49 V. Concluding Analysis...............................58 I. INTRODUCTION This study canvasses the interaction between terror threat announcements and the civil liberties/collective security balance during the three years after September 11, 2001. Part II considers how security threat environments alter the parity between collective security and civil liberties, but emphasizes that this shift is typically not from real, verified peril, but from perception of risk.' Part I11 addresses notable post-9/11 threat warnings and the detention of terror suspects.2 It inquires whether terror threat notifications were prudently issued and an imperative mechanism to apprise the populace of realistic and verified risks. -

Soff030a Revised Foreword .Indd

FOREWORD hroughout half of the 1980’s and into the early 90’s the Tprincipal target of the FBI’s New York Office was John J. Gotti, the notorious Boss of Bosses who ran the city’s most powerful crime family. Recently, after spending a decade in the research and writing of four investigative books for HarperCollins on the counterterrorism and organized crime failures of The Bureau * I came to realize that I had something in common with his son: John Angelo Gotti. Over the years both of us had become experts on the misconduct of various special agents and prosecutors working for the U.S. Department of Justice. There’s no doubt that Shadow of My Father will upend many of the public’s assumptions about that mysterious secret society of criminals J. Edgar Hoover mistakenly dubbed La Cosa Nostra. Written in John Junior’s own hand, it offers a rare inside look into “the underground kingdom” that was the Gambino family. * 1000 Years For Revenge: International Terrorism and The FBI The Untold Story (2003); Cover Up: What the Government Is Still Hiding About the War on Terror (2004); Triple Cross: How bin Laden’s Master Spy Penetrated The FBI, The CIA and The Green Berets (2006-2009); and Deal With The Devil: The FBI’s Secret Thirty-Year Relationship With A Mafia Killer(2013) . v vi Shadow of My Father This isn’t some ghost-written apologia told by an ex-wise- guy who cut a deal with the Feds and now lives under the protection of U.S. -

On the Heels of the Recent Brutal Murder of A

THE LETTER Oct 25, 2018 On the heels of the recent brutal murder of a The Washington Post journalist Jamal Khashoggi, President Donald Trump chose to celebrate the assault of The Guardian reporter Ben Jacobs by an American congressman—an attack that occurred while the journalist was simply doing his job, posing questions to a politician. Montana Congressman Greg Gianforte (R) body- slammed Jacobs, knocking him to the ground and beating him severely enough to send him to the hospital. Although Gianforte pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor assault and was fined, the President of the United States praised this violent behavior at a Trump rally in Missoula, Montana, on October 18. Trump’s condoning of political violence is part of a sustained pattern of attack on a free press— which includes labeling any reportage he doesn’t like as “fake news” and barring reporters and news organizations whom he wishes to punish from press briefings and events. One of the pillars of a free and open democracy is a vibrant free press. At his inauguration the President of the United States swears to protect the U.S. Constitution, including the First Amendment. 1 This President is utterly failing to do so and actively working not simply to undermine the press, but to incite violence against it as well. In a lawsuit filed by PEN, the writer’s organization, against Donald Trump, they charge him with violating the First Amendment. We, the undersigned, past and present members of the Fourth Estate, support this action. We denounce Donald Trump's behavior as unconstitutional, un-American and utterly unlawful and unseemly for the President of the United States and leader of the free world. -

The Falsified War on Terror: How the US Has Protected Some of Its Enemies

Volume 11 | Issue 40 | Number 2 | Article ID 4005 | Oct 01, 2013 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus The Falsified War on Terror: How the US Has Protected Some of Its Enemies Peter Dale Scott surveillance matters by its own Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, known as the German translation available FISA court, which according to the New York Times “has quietly become almost a parallel Before World War Two American government, Supreme Court.”3 Thanks largely to Edward for all of its glaring faults, also served as a Snowden, it is now clear that the FISA Court model for the world of limited government, has permitted this deep state to expand having evolved a system of restraints on surveillance beyond the tiny number of known executive power through its constitutional arrangement of checks and balances. All that and suspected Islamic terrorists, to any changed with America’s emergence as a incipient protest movement that might dominant world power, and further after the challenge the policies of the American war Vietnam War. machine. Since 9/11, above all, constitutional American Most Americans have by and large not government has been overshadowed by a series questioned this parallel government, accepting of emergency measures to fight terrorism. The that sacrifices of traditional rights and latter have mushroomed in size and budget, traditional transparency are necessary to keep while traditional government has been shrunk. us safe from al-Qaeda attacks. However secret As a result we have today what the journalist power is unchecked power, and experience of Dana Priest has called the last century has only reinforced the truth of Lord Acton’s famous dictum that unchecked power always corrupts. -

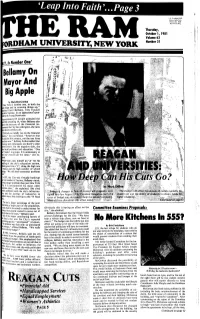

Nmscutsgo? Lit Was a Larger Problem Than Just New York Ity; It Is Encountered by Most Older Merican Cities," She Explained

'Leap Into Faith \..Page 3 US PoslagePAID Bronx. New York Permit No. 7608 Non-profit Org. Thursday, October 1,1981 Volume 63 IRPHAM UNIVERSITY, NEW YORK Number 21 Bellamy On Mayor And Big Apple by Maryellen Gordon New York is number one, in both the od things and in screwing things up," narked Carol Bellamy, City Council esident Tuesday, in an appearance1 spon- ied by the Young Democrats. Approximately 8 5 people attended the entheld in Keating 1st, where Bellamy also ited that because of the financial im- jvements the City has undergone, she rates pKoch's politics a B-, 'Ed Koch can validly run on the financial nation," she confirmed, "however that lyincludes this primary, not the one three arsfrom now." Bellamy further added that energy and enthusiasm are Koch's other isilive points. On the negative side, she ited racial problems and education. "One n't'pander' to groups. It is unnecessary to len one's mouth all the time," she ex- lined. While Koch rates himself an 'A' for his ndling of the city's education system, llamy gives him a 'C, citing the high rate truancy and the high number of school ings. "We still have enormous problems re." 11975, the City was virtually bankrupt e to a number of factors, Bellamy stated. nmsCutsGo? lit was a larger problem than just New York ity; it is encountered by most older merican cities," she explained. She cited , by Mark Dillon \" ' ;• '<\Jr irious problems with the city's infrastruc- . Sweeping changes in,fe,derai student aid programs were The changes will affect.the amount of money available foi\ and the outflux of industries to signed into law August 13 by President Reagaitas part of a student aid and the ability of students to obtain fund&'fprv Mhern states that built-up to the '75 fiscal series of budget cms designed tp'help the nation1^ economy, higher education. -

United States District Court for the District of Columbia

Case 1:10-cv-02119-RMC Document 44 Filed 11/02/12 Page 1 of 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ) ANTHONY SHAFFER, ) ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Civil Action No. 10-2119 (RMC) ) DEFENSE INTELLIGENCE AGENCY, ) et al., ) ) Defendants. ) ) MEMORANDUM OPINION Plaintiff Anthony Shaffer is an intelligence officer who was employed with the Defense Intelligence Agency, an operational component of the Department of Defense, from 1995-2006. After this, he joined the U.S. Army Reserve and retired as Lieutenant Colonel in 2011. Mr. Shaffer served two tours of duty in Afghanistan. Together with a ghost writer, Mr. Shaffer authored a book entitled Operation Dark Heart: Spycraft and Special Ops on the Frontlines of Afghanistan and the Path to Victory, which he describes as an eyewitness account of the 2003 “tipping point” of the war in Afghanistan. He is required by several secrecy agreements to submit all of his writings for prepublication review to ensure they do not contain classified information. Mr. Shaffer complains that several executive agencies improperly designated certain information in his book as classified and imposed a restraint on his First Amendment right to publish his book. The agencies assert that Mr. Shaffer lacks standing to bring his claim because he sold control of his book to his publisher in the United States; they move to dismiss the Amended Complaint. The motion will be denied. Mr. Shaffer has standing Case 1:10-cv-02119-RMC Document 44 Filed 11/02/12 Page 2 of 8 because he maintains rights to publish an unredacted version of his book and, if the redactions are overbroad, to otherwise “publish” the non-classified information in his book.